Simon Fraser / Science Photo Library

Older adults who are prescribed benzodiazepines for longer than three months are up to 50% more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease, new research indicates. However, two leading mental health pharmacists have warned that this does not necessarily mean the drugs are the cause of the disease.

Benzodiazepines are commonly used to treat symptoms of insomnia and anxiety, but they are well known to have a damaging effect on short-term memory and cognition, say the authors of the study. Guidelines from the Royal College of Psychiatrists recommend that benzodiazepines should not be used for longer than four weeks, yet their use remains widespread among older patients.

Caroline Parker, consultant pharmacist in mental health at Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, says the long-term prescription of benzodiazepines is not advised for a number of reasons, including the risk of falls, the chance of dependence and the impact on cognition, particularly in the case of long-acting benzodiazepines or for the elderly. “Therefore this study emphasises further that the long-term use of benzodiazepines is not advisable,” Parker says.

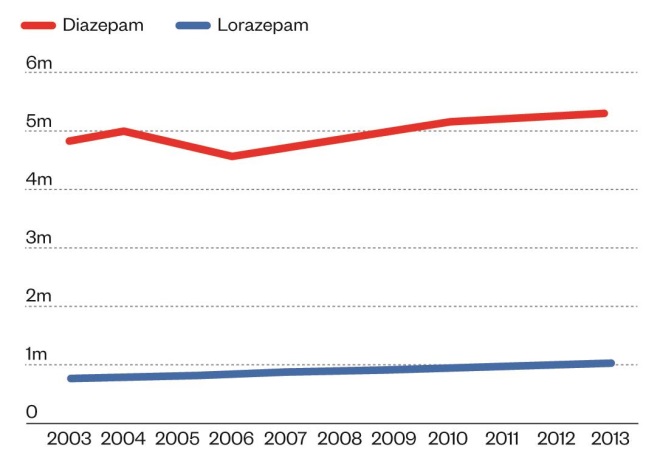

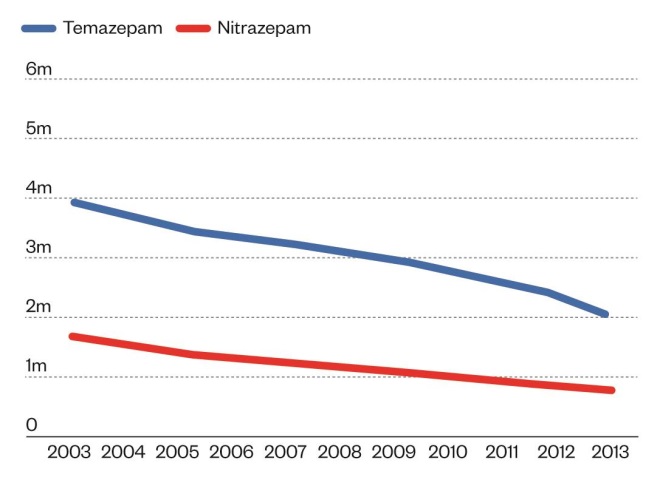

In the UK, the use of the benzodiazepines temazepam and nitrazepam for insomnia decreased by almost half between 2003 and 2013. However, the use of diazepam and lorazepam for anxiety has increased in this time period, although to a much smaller degree (see graphs).

Source: Health and Social Care Information Centre

Hypnotic items dispensed in England, 2003-2013

Source: Health and Social Care Information Centre

Hypnotic items dispensed in England, 2003-2013

Previous studies have found an association between use of the drugs and an increase in risk of dementia in later life, however, the exact nature of the relationship between benzodiazepines and dementia has been a matter of debate. Insomnia and anxiety can be early symptoms of the disease, which could account for the increased use of benzodiazepines in these patients.

But in the latest study published in the BMJ

[1]

(online, 9 September 2014), researchers in Canada aimed to disentangle this complicated relationship by only looking at the use of benzodiazepines at least six years before a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, which is the most common type of dementia.

In Quebec, 98% of older people are covered by the national drug plan and information on prescriptions and medical services are recorded in the Quebec health insurance programme database. Using this population of patients, those aged over 66 years with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s (n=1,796) were matched with four patients without dementia who were the same age and sex, and who had been tracked in the system for the same length of time (n=7,184).

Exposure to benzodiazepines between six and ten years before the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s — or the equivalent date for the control group — was compared between the groups, as well as cumulative exposure and duration of action of the drug.

Overall, 49.8% of patients with Alzheimer’s had ever used benzodiazepines, compared with 40.0% without Alzheimer’s. Patients who had ever been exposed to benzodiazepines had an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (adjusted odds ratio 1.50, 95% confidence interval, 1.36–1.69). When this figure is broken down, cumulative exposure of up to three months was not associated with an increased risk (OR 1.09, 95% CI, 0.92–1.28). Use of benzodiazepines for longer than this was found to increase the association with Alzheimer’s; between three to six months (OR 1.32, 95% CI, 1.01–1.74) and for longer than six months (OR 1.84, 95% CI, 1.62–2.08) and the association was stronger for longer-acting benzodiazepines (OR 1.70, 95% CI, 1.46–1.98) compared with short-acting benzodiazepines (OR 1.43, 95% CI, 1.27–1.61).

However, pharmacists said that interpretation of the results is fraught with uncertainty. Parker cautions that addressing a question like this is “extremely difficult” due to the number of confounding factors and the length of time required to anticipate the onset of an illness and to distinguish between cause and effect.

“Case control studies are always difficult to interpret because of the risk of confounding by indication,” says specialist mental health pharmacist David Taylor, director of pharmacy and pathology at King’s Health Partners. “Do benzodiazepines cause or hasten the onset of Alzheimer’s or do people later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s use benzodiazepines to treat early symptoms associated with the condition? We can never really know.

“Nonetheless, the linear association with the duration of benzodiazepine treatment in this study is an important reminder to adhere to long-standing recommendations on limiting benzodiazepine treatment to only a few weeks.”

The authors of the study also acknowledge that a causal relationship cannot be definitively established and they call for long-term studies of at least 20-30 years, as well as animal studies that could identify a biological mechanism for the association. However, the authors of an accompanying editorial[2]

believe the results suggest that long-term exposure to benzodiazepines might be a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s and that “the interpretation of these findings is strengthened by [the] rigorous methods” of the study. They are critical of the fact there is currently no standardised approach to identify and monitor the cognitive side effects of drug treatments and they advocate that a “global surveillance system” should be established using electronic medical records.

References

[1] Billioti de Gage, Moride Y, Ducruet T, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: case-control study. The BMJ 2014;349:5205. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5205

[2] Yaffe K, Scola R, Scola M, et al. Benzodizepines and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. The BMJ 2014;349:5312. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5312