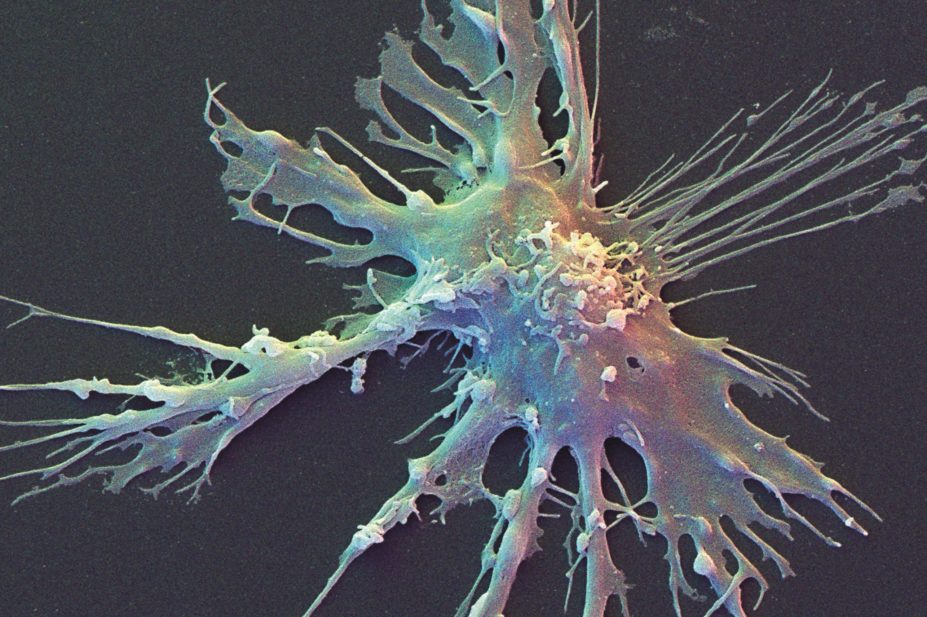

David Scharf / Science Photo Library

Researchers have created personalised vaccines for patients with advanced melanoma for the first time, the results of a trial suggest.

Scientists gave three patients vaccines that targeted unique markers on their tumours, finding they had enhanced and broadened immune responses.

The personalised approach used in the trial stems from the knowledge that some melanoma patients have an immune response to proteins produced as a result of mutations in their tumours. The researchers at the Washington University school of medicine in St Louis, Missouri, hypothesised that by stimulating a more robust immune response against these proteins the immune system would recognise the tumour as foreign.

In the study, published in Science

[1]

on 2 April 2015, the researchers analysed the cancer genome of three patients to identify mutations that would lead to “neoantigens” — protein fragments that are different in tumour cells compared with healthy cells. From the hundreds of neoantigens identified, a set of seven was chosen that was unique to each patient. The criteria for the choice of these seven neoantigens were based on whether they were expressed by the tumour as proteins and on their affinity for molecules that present the antigens to the immune system. In this way, vaccines were created that precisely targeted each individual’s tumour.

The researchers found that vaccination increased the T cell response to patients’ specific tumour markers. “All three patients had pre-existing immunity to at least one neoantigen and vaccination revealed new immunity to two additional neoantigens,” says Beatriz Carreno, associate professor of medicine at Washington University school of medicine, and lead author of the study. She says that immunity to multiple tumour antigens is important, since a diverse response might reduce the likelihood that the cancer will evolve to evade the immune system.

“Vaccination promotes a highly diverse repertoire of neoantigen-specific T cells, suggesting that cancer patients have a potentially rich pool of naive tumour-specific T cells that remain dormant until activated by vaccination,” she added.

All three patients had stage III resected melanoma that had already been treated with ipilimumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor for advanced melanoma, before the study. The proof-of-concept trial was designed to assess whether there was an immune response and if the personalised vaccine was safe; it was not designed to assess the vaccine’s therapeutic effect. However, the researchers report that all three patients are alive and in a stable condition.

To create the vaccines, the researchers incubated a sample of each patient’s dendritic cells — which can stimulate a powerful response from T cells — with the chosen set of antigens. The vaccines were then administered via three intravenous infusions, over the course of 18 weeks. The patients’ immune responses to the peptides peaked at eight to nine weeks after vaccination. No safety concerns were identified.

One of the limits of the therapy is that it takes three to four months to create each vaccine, but the researchers hope to shorten this timeline as the technology develops.

The authors believe that immunotherapy with a personalised dendritic cell vaccine could become feasible in the near future and that this kind of approach could also be used in other cancers with a high burden of mutations, such as lung, bladder and colorectal cancers. They are considering whether using immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment at the same time as the vaccine could further enhance the immune response — immune checkpoint inhibitors help switch off the cellular system that dampens the body’s natural response to tumours.

The patients have now been enrolled in a phase I clinical trial, which the researchers say will begin in nine to twelve months.

References

[1] Carreno BM, Magrini V, Becker-Hapak M et al. A dendritic cell vaccine increases the breadth and diversity of melanoma neoantigen-specific T cells. Science 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3828.