BSIP SA / Alamy Stock Photo

Key points:

- The range of over-the-counter analgesics can make it difficult for patients to select the appropriate medicine to self-manage their pain.

- Pharmacy teams should be able to confidently support and work together with patients to help them make an informed choice, putting them at the centre of decisions about their treatment.

With so many over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics available, it can be confusing for patients looking to self-manage their acute pain symptoms[1]

. However, pharmacists and members of the pharmacy team can provide the expert advice and support that patients require to make an informed choice[2],[3]

.

Opportunities for pharmacy in self-care

Encouraging patients to self-care has long been the role of pharmacists. In England, this was formalised in 2005 with the introduction of the ‘Community pharmacy contractual framework’, which made self-care an essential service and has been supported in successive years with the NHS’s ‘Five-year forward view’ and NHS England’s move in 2018 to cease prescribing certain available OTC medicines[4],[5],[6]

,[7]

.

In 1998, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that pharmacists have many different roles in self-medication and self-care, including:

- Communication;

- Provision of quality medication;

- Training and supervising (support staff);

- Collaboration (with the patient and other healthcare professionals);

- Provision of health promotion advice[8]

.

The trusted and accessible nature of the community pharmacy team provides opportunities to support patients to make safe and appropriate choices on how best to self-manage minor conditions[9]

. A survey carried out by The Pharmaceutical Journal in 2018 revealed that around 35% pharmacists spoke to adult patients about acute pain between two and five times per day, demonstrating the opportunity for pharmacy to influence patients’ attitudes and decisions on self-care and self-medication for pain relief[10]

.

This potential was acknowledged by experts at a round table event on acute pain, hosted by The Pharmaceutical Journal in 2018. However, the panel suggested a shift in perspective by the pharmacy team was required when speaking to patients, allowing for a more holistic and patient-centred approach[10]

.

Managing acute pain

Acute pain is defined as pain lasting less than three months or pain relating to soft tissue damage[11],[12]

. It serves as a warning to alert the body to a problem, with the aim of preventing further tissue injury[13]

, and is often proportional to the severity of injury, often resolving when tissue healing is complete.

There are a variety of OTC treatments available, including pharmacological options containing paracetamol, ibuprofen or aspirin and non-pharmacological treatment options, such as heat patches.

The evidence base and guideline recommendations for first-line treatment vary based on the presenting complaint. Additional factors, such as clinical presentation, patient comorbidities and contraindications, need to be considered when supporting patients with the best options for self-care, in order to address misconceptions. More information on clinical guidelines and the evidence base for acute pain management has been outlined in a previous article (see ‘Clinical guidelines and evidence base for acute pain management’).

The pain consultation

A widely-recognised approach to patient consultations is the Calgary–Cambridge model, which is commonly used as the framework for healthcare professional-patient consultations, with an emphasis placed on including patients in decisions about their care, the importance of active listening and use of open questions[14]

. Acute pain consultations can be conducted by any member of the pharmacy team, provided they are competent to do so.

Steps in the Calgary–Cambridge model include:

- Initiate the consultation and build rapport;

- Gather information;

- Shared decision making, including the discussion of treatment options alongside patient education (e.g. dosage, administration, what to expect in terms of symptom relief and relevant signposting);

- Summarise and close the consultation[14]

.

Although every consultation will be different, these methods can be used to ensure the essential points of an impactful consultation are achieved.

1. Initiate the consultation and build rapport

As with any consultation, patients presenting with acute pain should be made to feel comfortable while discussing their symptoms. This could be through simple steps such as offering the opportunity to talk in the consultation room or, if possible, to speak to a member of the pharmacy team of the same gender or have a chaperone present. Previous studies have shown patient preference towards having consultations in an environment where their privacy is protected[15]

,[16]

.

The pharmacist or team member should then introduce themselves and ask the patient the purpose for them visiting the pharmacy[14]

.

“Hello. My name is … what brings you to the pharmacy today?”

Consultations in which the presenting patient asks for a specific medicine or product by name should be treated in a similar manner. It is important for the entire pharmacy team to be aware that, although the patient may be requesting a product, it may be inappropriate. In this situation, the patient may be unsure, or even irritated, as to why you are asking them further questions. Therefore it is important to communicate that these questions are being asked to ensure they receive the most appropriate and effective treatment for their pain. This aligns with the Calgary–Cambridge guide to negotiate the agenda with the patient[14]

.

“Before I can sell you this product, I would like to ask you a few questions to help ensure we are providing you with the best possible treatment. If you prefer, we can discuss this in the consultation room.”

2. Gather information

Ask open questions

By asking open questions, the patient will feel encouraged to open-up about their history and acute pain experience[14]

, rather than simply asking questions that get a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response (see Box 1). The pharmacist or team member should be conscious of their use of verbal and non-verbal communication. In addition, it is necessary to confirm understanding of what the patient has said.

Box 1: Consultation points for acute pain

Pharmacy teams should focus on the following areas when discussing acute pain with a patient:

Location — “Where does it hurt?”

Duration / onset — “When did the pain start?”; “Do you have any ideas about what might have caused it?”

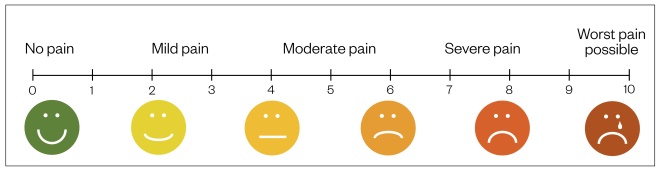

Intensity — “How would you rate the pain?” (Use a rating scale to assess the level of pain).

Description of pain — “Can you describe what the pain feels like?”; “Does it feel like a dull ache or sharp, stabbing pain?”

Impact on day-to-day life — “Over the past two weeks, do you think your pain has been bad enough to interfere with your day-to-day activities?”; “Over the past two weeks, have you felt worried or low in mood because of this pain?”; “How does it make you feel?”

Previous treatment — “What have you tried previously?”; “Do you think this helped?”; “How frequently are you using it?”

Common mnemonics, such as WWHAM and ASMETHOD, can be used to help guide what questions to ask, but patients may feel that their scripted nature feels intrusive, especially if this takes place at the pharmacy counter[17]

.

WWHAM

- W ho?

- W hat?

- H ow?

- A ction?

- M edicines?

ASMETHOD

- A ge/appearance?

- S elf or someone else?

- M edicines?

- E xtra medicines?

- T ime persisting?

- H istory?

- O ther symptoms?

- D anger symptoms?

There are alternatives to this method that may feel less intrusive and encourage patients to share information, such as the TED and ICE principals[18]

:

TED

T — Can you tell me why you have come into the pharmacy today?

E — Can you explain who the medicine is for and what the problem is?

D — Please describe your symptoms and how long you have had them?

ICE

I — What are your ideas about what may have caused it?

C — What is a concern to you?

E — What were your expectations from your visit to the pharmacy?

Although exact questions do not need to be used prescriptively, these should act as a guide when asking patients open questions. It is important to establish any other medicine that the patient is taking or if they have any conditions that could influence treatment choice. In addition, there is a need to rule out red flags (see Box 2).

Assess the level and location of pain

Pain is a subjective experience; therefore, it can be difficult to determine the level of pain the patient is experiencing[19]

. The Faculty of Pain Medicine has developed two questions as an early pre-screening tool that focus on quality of life and the effects of the pain experienced (see Box 1):

“Over the past two weeks, has your pain been bad enough to interfere with your day-to-day activities?”

“Over the past two weeks, have you felt worried or in a low mood because of this pain?”

[20]

.

Pain assessment scales, such as Numerical Rating Scales (NRS), Verbal Rating Scales (VRS) and the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, are an effective way for the patient to communicate just how bad their pain is and to measure changes in the intensity of the pain[21]

. An example of a rating scale that uses various faces to depict pain, similar to the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, can be seen in the Figure. These are suitable for use in the community pharmacy setting to help determine the level of pain a patient is experiencing.

Figure: Pain measurement scale

Source: Shutterstock.com / JL

The choice of assessment scale may be influenced by setting and the age of the patient, and their ability to communicate. For example, the Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale is particularly useful for rating pain in children aged three years and over or for patients who have communication difficulties, such as language barriers[21]

.

A systematic review published in 2018 showed the visual analogue scale (VAS), VRS and NRS to be valid and reliable tools, with the NRS having good sensitivity to changes in the intensity of the patient’s pain[22]

.

Box 2: Red flags for patients with acute pain

These are general red flags associated with acute pain; however, this list is not exhaustive; professional judgement should be exercised based on potential causes of the pain.

- Bleeding;

- Pain from the central spinal pain region;

- Difficulty breathing or maintaining circulation;

- Dizziness;

- Fever;

- Gradual onset pain;

- Headache that worsens on standing or lying down;

- History of recent physical trauma;

- Impaired consciousness;

- Loss of physical function, particularly asymmetrical;

- Neck pain or stiffness with photophobia (i.e. sensitivity to light);

- Preceding recent head trauma (usually within past three months);

- Progressive or persistent headache or headache that has changed dramatically;

- Unexplained seizure;

- Severe, unremitting pain;

- Sudden onset severe headache, reaching maximum intensity within five minutes;

- Unexplained weight loss;

- Visual disturbance.

Where a red flag is identified, the patient should be referred to an appropriate healthcare provider, such as their GP or hospital emergency department. Consideration should be given as to whether pain relief should be provided in the interim.

Sources: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[23],[24]

; Practice Nurse

[25]

Ask closed questions

Closed questions can be used towards the end of the consultation to gather any specific points that may have been missed.

3. Shared decision making and discussion of treatment options

In patients presenting with mild-to-moderate acute pain, in the absence of red flag referral criteria (see Box 2), the next step is to discuss potential treatment options.

National guidance on medicines adherence suggests that patients are more likely to adhere to a medicine regime when they have been involved in the decision about what options are available and where there has been consideration towards how taking the medicine will fit into their daily routine[26]

.

Shared decision-making draws on the expertise of both the healthcare professional and the patient[27]

. While the pharmacist understands the analgesics available and the associated evidence supporting their use, the patient can tell the pharmacist what their preferences and values are; both sources of information are needed for high-quality decision making.

Educate patients and manage expectations

It is important to understand what the patient knows about their pain and what their expectations are in terms of recovery and the effect of any treatment recommended. Start by asking the patient open questions, such as:

- “What do you know about the cause of your pain?”;

- “What are you hoping treatment will do for you?”.

When discussing treatment options, BRAN is a useful mnemonic to use:

- B enefits — what are the benefits of the treatment?

- R isks — what are the risks of the treatment?

- A lternatives — what are the alternative treatments available?

- N othing — what might happen if the patient does nothing?[28]

It is important to ask the patient questions that will help to identify whether each option will suit their lifestyle, such as:

“Would it be convenient for you to apply a cream throughout the day?”;

“How would you feel about taking the medicine every four hours?”.

The management of acute pain can be likened to the principles of the WHO’s ‘Cancer pain ladder for adults’, with the initial OTC management targeted at the use of non-opioids (e.g. paracetamol or ibuprofen), before stepping up to low-dose opioids (containing codeine or dihydrocodeine)[29]

.

Recommendations for the management of mild-to-moderate pain should follow local and national guidance, such as that contained within the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s Clinical Knowledge Summary for mild-to-moderate pain and the manufacturer’s product licenses[30]

.

An important consideration is whether the patient wants to be treated pharmacologically, if at all. It is an easy assumption to make that a patient presenting in the pharmacy is looking for medical treatment, but this may not be the case. The patient may only be seeking supportive advice or a diagnosis. Non-pharmacological management, such heat packs, may be beneficial to patients; therefore, training on the use of such products should be made available to the pharmacy team to help empower them during pain consultations.

4. Summarise and close the consultation

Once agreement has been reached on which treatment path to follow, the final step in the consultation is to utilise the ‘teach-back’ method; this is where the pharmacist or team member asks the patient to summarise what they are going to do[31]

. This will confirm if the patient has understood what has been discussed.

If needed, additional support can be provided (e.g. providing the patient with written information). Where necessary, a timeline for follow-up should be agreed and the patient reminded that they can return to the pharmacy for support should they need it[14]

.

Following the consultation, it is good practice to document and record the outcomes of interesting or particularly difficult or complex consultations, such as where additional intervention or referral may have been required, as this can be used to support reflective practice and annual performance reviews.

It is important to remember that the patient’s experience is individual to them and that it is necessary to be sensitive when discussing their pain. Statements such as “that must be really frustrating” or “I am sure that it is difficult managing your pain everyday” can help show empathy and improve the patient’s willingness to open up and discuss their issues.

Some patients may not want to take medicine to manage their pain in the hope that it may pass. If this is the case then you can outline the evidence base for acute pain management (see ‘Clinical guidelines and evidence base for acute pain management’) and explain that with suitable treatment they could achieve relief from their pain.

There is a need to be aware of oversharing with the patient. Some pharmacy staff may feel that sharing their personal experience will help patients relate and open up; however, this should be avoided as it risks the patient simply mirroring what the staff member says or, due to the limited time available for a consultation, it may cause a lost opportunity for the patient to share their own experience.

Although a consultation should feel natural — like a conversation — the entire pharmacy team must remember they need to gather information and educate the patient. Therefore, there needs to be a balance between being concise and encouraging the patient to contribute.

When possible, opportunities for the patient to ask questions should be offered, because this will help clarify any misunderstanding and potentially improve patient engagement.

Safety, mechanism of action and efficacy of over-the-counter pain relief

These video summaries aim to help pharmacists and pharmacy teams make evidence-based product recommendations when consulting with patients about OTC pain relief:

- Safety of over-the-counter pain relief

- Mechanism of action of over-the-counter pain relief

- Efficacy of over-the-counter pain relief

Promotional content from Reckitt

References

[1] Wazaify M, Shields E, Hughes CM & McElnay JC. Societal perspectives on over-the-counter (OTC) medicines. Family Practice 2005;22(2):170–176. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh723

[2] Perrot S, Cittée J, Louis P et al. Selfâ€medication in pain management: the state of the art of pharmacists’ role for optimal over-the-counter analgesic use. European J Pain 2019;00:1–16. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1459

[3] Bell J, Dziekan G, Pollack C & Mahachai V. Self-care in the 21st century: a vital role for the pharmacist. Adv Ther 2016;33(10):1691–1703. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0395-5

[4] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. 2018. Support for self-care. Available at: https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/essential-services/support-for-self-care (accessed December 2019)

[5] NHS England. Five year forward view. 2014. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[6] NHS England. Conditions for which over the counter items should not routinely be prescribed in primary care: Guidance for CCGs. 2018. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/conditions-for-which-over-the-counter-items-should-not-routinely-be-prescribed-in-primary-care-guidance-for-ccgs (accessed December 2019)

[7] NHS England. Why can’t I get a prescription for an over the counter medicine? 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/medicines/why-cant-i-get-prescription-over-counter-medicine (accessed December 2019)

[8] World Health Organization. The role of the pharmacist in self-care and self-medication – report of the 4th WHO consultative group on the role of the pharmacist. 1998. Available at: https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jwhozip32e (accessed December 2019)

[9] Robinson J. Is a complete ban on OTC opioids the solution? Pharm J 2019;301(7926):338–342. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2019.20206655

[10] Robinson J. Pharmacists should do more to help patients with OTC analgesics, experts say. Pharm J 2019;302(7922):81–83. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2019.20205474

[11] British Pain Society. Useful definitions and glossary: pain. British Pain Society. 2015. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/people-with-pain/useful-definitions-and-glossary/#pain (accessed December 2019)

[12] Veritas Health. Acute pain definition, Spine-health. Available at: https://www.spine-health.com/glossary/acute-pain (accessed December 2019)

[13] Youssef S. Clinical guidelines and evidence base for acute pain management. Pharm J 2019;303(7929):44–48. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2019.20206653

[14] Silverman J, Kurtz S & Draper J. Calgary-Cambridge guides communication process skills. Skills for communicating with patients. 3rd edition. London: Radcliffe Publishing; 2013.

[15] Hattingh HL, Emmerton L & Green C. Utilisation of community pharmacy space to enhance privacy: a qualitative study. Health Expect 2015;19:1098–1110. doi: 10.1111/hex.12401

[16] Hattingh HL, Knox K, Fejzic J et al. Privacy and confidentiality: perspectives of mental health consumers and carers in pharmacy settings. Int J Pharm Pract 2014;23(1):52–60. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12114

[17] Paul R. Community Pharmacy: symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. 4th edn. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2017

[18] Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. Consultation skills for pharmacy support staff. 2016. Available at: http://www.consultationskillsforpharmacy.com/docs/CounterCardsforweb.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[19] Giordano J, Abramson MA & Boswell MV. Pain assessment: Subjectivity, objectivity and the use of neurotechnology Part One: Practical and ethical issues. Pain Physician 2010;13:305–315. PMID: 20648198

[20] Faculty of Pain. ASK2QUESTIONS. 2019. Available at: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/faculty-of-pain-medicine/ask2questions (accessed December 2019)

[21] Pain Doctor. 15 pain scales (and how to find the best pain scale for you). 2018. Available at: https://paindoctor.com/pain-scales (accessed December 2019)

[22] Karcioglu O, Topacoglu H, Dikme O & Dikme O. A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: Which to use? Am J Emerg Med 2018;36(4):707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.008

[23] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Analgesia: Headache Clinical Knowledge Summary. 2017. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/headache-assessment#!scenarioRecommendation:1 (accessed December 2019)

[24] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain Clinical Knowledge Summary. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/back-pain-low-without-radiculopathy#!diagnosisSub:1 (accessed December 2019)

[25] Lowth M. Recognising red flags. Practice Nurse 2016;46(1):23

[26] Nunes V, Neilson J, O’Flynn N et al. Clinical guidelines and evidence review for medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. 2009. National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg76/evidence/full-guideline-242062957 (accessed December 2019)

[27] Coulter A & Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. The Kings Fund and Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making. 2011. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[28] Choosing Wisely UK. Shared decision-making resources. 2019. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.co.uk/resources/shared-decision-making-resources (accessed December 2019)

[29] World Health Organization. WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults. 2002. Available at: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en (accessed December 2019)

[30] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Analgesia: mild-to-moderate pain. Clinical Knowledge Summary. 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/analgesia-mild-to-moderate-pain# (accessed December 2019)

[31] The Health Literacy Place. Teach back. NHS Education for Scotland. 2019. Available at: http://www.healthliteracyplace.org.uk/tools-and-techniques/techniques/teach-back (accessed December 2019)

You might also be interested in…

Calling the shots: the pharmacists combatting vaccine misinformation

Embedding quality improvement in pharmacy practice: a departmental strategy at University Hospitals of Derby and Burton