Peter Farley

I work two days per week as a pharmacist in the multidisciplinary chronic pain team in South Staffordshire, which forms part of Midlands Partnership NHS Foundation Trust.

The team includes physiotherapists, psychologists, occupational therapists and consultant medics. Patients are referred to the chronic pain service by their GP in order to receive further guidance on pain management.

My role is threefold: to undertake patient medicine reviews; to keep team members up to date with important aspects of pain medicines; and to give group presentations to patients undertaking the South Staffordshire pain management programme. This comprises six half-day sessions where patients are introduced to the most effective ways of treating chronic pain.

09:00 — start

This morning, I am in clinic. Patients are referred from other members of the team if there are concerns over use of pain medicines or for help with long-term opioid therapy management. During a normal clinic, I will review three patients.

Most of the people I see have ‘chronic pain of unknown origin’. This is unlike acute pain and is defined as pain that lasts longer than would be expected from the healing processes involved and is independent of any other underlying illness or injury.

Once it starts, it is unlikely chronic pain of unknown origin will go away completely and may last for the rest of the patient’s life.

I always start consultations with the following: tell me about your pain; tell me about your pain medicines; and tell me which of these medicines help with your pain. I find that patients have rarely had the opportunity or felt empowered to address this last question.

My first patient has recently been diagnosed with fibromyalgia — a condition that causes pain all over the body — but describes worsening pain since leaving an abusive relationship 20 years ago. Their prescribed pain medicines are co-codamol 30/500mg (two tablets four times daily) and pregabalin 300mg (one twice daily). When the fibromyalgia diagnosis was confirmed, the dose of pregabalin was gradually increased from 200mg twice daily to 300mg twice daily. Since then, the patient has noticed their sentences sometimes stop abruptly when they talk, and they express concern about the onset of senility.

They reveal that neither the co-codamol nor the pregabalin provide much benefit. After 20 years of regular codeine dosing, it is likely that they will have developed a high tolerance.

Use of strong opioids is now questionable in the treatment of chronic pain and can, paradoxically, worsen it

We discuss how the patient can accurately determine the efficacy of their pain medicines. This involves changing one medicine at a time, as changing more than that will cause confusion. Most of the medicines used in the treatment of chronic pain of unknown origin are standard pain medicines taken two, three or four times per day.

Therefore, I usually suggest patients extend the period between one specific dose each day and the next by 30-minute intervals on sequential days. If the medicine is giving benefit, then at some point their pain will increase. However, if the time period extends to the next scheduled dose without symptoms recurring, then I suggest they discuss the efficacy of their medicine with their GP.

The patient and I agree on a review appointment in three months and I write a letter to their GP suggesting possible changes to therapy — replace co-codamol with paracetamol 500mg (two tablets four times daily), and dihydrocodeine (DHC) 30mg (one or two tablets up to four times daily, as necessary). There is unlikely to be any cross-tolerance between codeine and DHC, which should minimise withdrawal symptoms. I also recommend replacing pregabalin with another therapy for fibromyalgia — either gabapentin or amitriptyline — and slowly increasing the dose before reappraising.

10:00

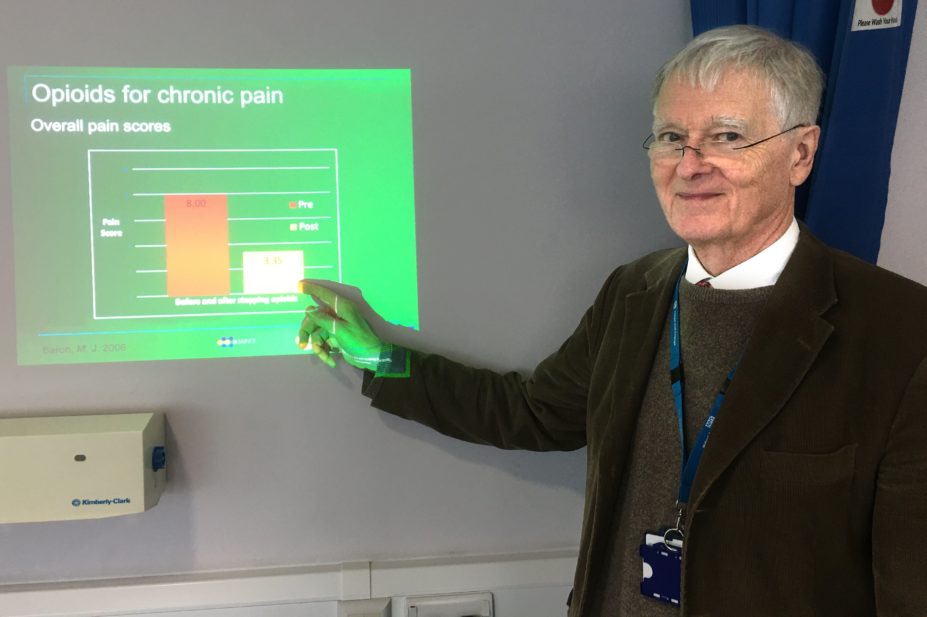

My second patient is already known to me. I am working closely with their GP to reduce their sustained-release morphine (600mg twice daily) dose, initiated and facilitated by previous prescribers. Consistent, long-term opioid use is associated with tolerance, dependence and addiction. Use of strong opioids is now questionable in the treatment of chronic pain and can, paradoxically, worsen it.

From our conversation I understand that the dose reduction is slow and proceeds in ‘fits and starts’; however, the dose escalation has taken many years and it is unreasonable to expect that reduction should be significantly quicker — especially as we are trying to avoid unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. Although there is concern over being misled by this patient’s addiction, I am encouraged that their daily morphine dose has reduced by about 200mg over the past 12 months.

11:00

I review a patient who I have seen twice before, who had initially reported significant neuropathic symptoms. They had been taking co-codamol and had slowly increased their amitriptyline to 40mg at night before bed. Although this dose had reduced their neuropathic symptoms, it had made them very drowsy in the mornings and they struggled to do anything before 11:00.

At their initial appointment, we discussed how they could reduce the sedative effects of amitriptyline after waking by taking the dose earlier in the evening. This change had helped, but left them considering how much pain they could tolerate to minimise the remaining sedation. Consequently, I suggested a change to nortriptyline, which is reported to cause less sedation. At this appointment, the patient confirmed almost total relief from their neuropathic symptoms with minimal ongoing sedation.

This is a niche role in which pharmacists can employ their unique skillset

13:00

I spend the afternoon delivering a patient presentation as part of the pain management programme. I set out the general guidance for using pain medicines effectively for chronic pain. Patients can then apply this to help them best manage their pain according to their circumstances.

This is followed by an opportunity for questions, which tend to fall into two groups. The first are those which demonstrate minimal understanding about medicines in general and analgesics in particular. Answering these questions requires careful assessment of comprehension and baseline understanding. Others demonstrate more knowledge and often relate to information circulating in the press and online.

Almost inevitably, someone seeks information about cannabidiol (CBD) oil. Unless questioned directly, I limit myself to only appropriate pharmaceutical safety advice. I remind patients that they will have to pay for this and, as a result, they need to be sure of benefit and to only purchase CBD from a reputable supplier. I also warn patients that there is very little regulation for such products.

We conclude with a discussion about unusual side effects of medicines. This provides excellent opportunities for reflection and continuing professional development.

17:00 — finish

Today has been a most rewarding day. This is a niche role in which pharmacists can employ their unique skillset, empowering patients to use their medicines in ways that are appropriate for the treatment of their pain.

When I first started in this role, I believed that regular analgesia would significantly improve the patient’s pain. Over the past seven years I have learned that the reality for most chronic pain patients is that nothing in the current pharmacopeia will make them pain free.

I have also learned that each patient’s pain is known only to themselves. The best that can be achieved for most patients is that the appropriate use of the best medicine will mitigate their pain, facilitating the things that are important, but they know will still cause them pain.

Box: Are you interested in a similar role?

- My role is NHS Agenda for Change band 8A;

- Pharmacist involvement within the chronic pain service is very limited and there is need for the pharmacist’s skill set both for treatment and research;

- The need for treatment of chronic pain of unknown origin is immense and most clinical commissioning groups will have contracted for this either in the community or in a local hospital;

- The British Pain Society has a lot of information about chronic pain of unknown origin and pain management programmes;

- You will need to develop a new skill set because chronic pain of unknown origin needs to be treated differently to acute pain. It varies from day to day and, therefore, pain medicines should vary as well. I am not aware of any specific courses that are available for pharmacists, but I would be willing to offer guidance to anyone thinking that this role might be of interest;

- You will probably be surprised by how little patients understand their medicines. The most important question is “Do your medicines help with your pain?”.