Science Photo Library

Impetigo is a highly contagious skin infection caused when bacteria enters damaged or broken skin and is most common in young children aged up to four years. In England and Wales, the incidence of impetigo in children aged 0 to 4 years is 84 per 100,000, and 54 per 100,000 in children aged 5 to 14 years[1]

.

Impetigo infection usually self-resolves within two to three weeks; however, with effective treatment, infection should resolve in seven to ten days[2],[3]

.

While impetigo generally affects the upper layer of the skin, secondary infections and complications (see below) can occur, which may be life-threatening if left untreated[3]

.

This article outlines the symptoms of active infection, appropriate management, prevention and when to refer.

Symptoms

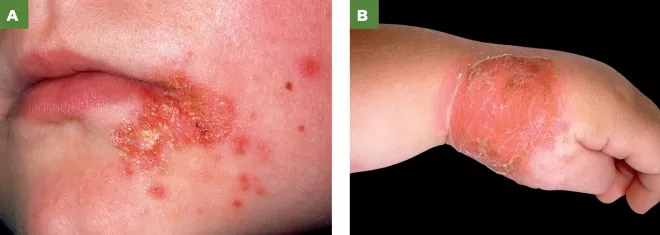

Two forms of impetigo exist: non-bullous (the most common type) and bullous. Their main differences are summarised in Table 1 and can be seen in photoguides A and B[2],[3],[4]

.

Both types begin with the appearance of multiple lesions; either small, red vesicles or sores that burst and dry to form yellow crusting. This may then extend and spread to other parts of the body. Redness varies with natural skin colour; therefore, in patients with darker skin pigmentation, sores with hyperpigmentation would be seen[5],[6]

.

Common infection sites include the face (e.g. around the nose and mouth), flexures, hands and limbs, but infection can also occur on other areas of the body, such as on the abdomen, buttocks and perineal regions[3]

.

| Non-bullous | Bullous |

|---|---|

| Source: NICE 2,4, NHS inform 3 | |

|

|

Photoguide: Non-bullous and bullous impetigo

Source: Science Photo Library

A: Non-bullous impetigo lesions

B: Bullous impetigo. Close-up of a rash on the hand of a child aged 4 years with bullous impetigo

Causes and transmission

Infection occurs because of a break in the skin (e.g. a cut, scratch or insect bite) or an underlying skin condition (e.g. eczema, scabies, herpes simplex, burns)[3]

.

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is the most common causative organism for impetigo in the UK; however, Streptococcus pyogenes, which may co-exist with S. aureus and methicillin-resistantS. aureus (MRSA), are also causative agents[4],[7]

.

Transmission occurs directly through close contact with an infected person (commonly via hands) or indirectly via contaminated objects (e.g. toys, clothes, towels). It has an incubation period of four to ten days; therefore, infection is often transmitted unknowingly[4]

. It is no longer infectious once patches crust over or following 48 hours of antibiotic treatment.

Risk factors

Humid weather, crowded areas, poor hygiene and pre-existing skin conditions (e.g. eczema) are risk factors for developing impetigo[4]

. As impetigo is contagious, should a significant local outbreak in a school or nursing home occur, or is suspected, referral to the local health protection team is required[4],[8],[9]

.

Immunocompromised patients are more prone to developing complications and if widespread infection is present then patients should be referred to secondary care based on clinical judgement [4]

.

Diagnosis

A formal diagnosis is based solely on history and clinical appearance , with further questioning to rule out other conditions[4]

. History-taking should include onset, duration and location of lesions and potential sources of infection (e.g. skin trauma, insect bites and contact with those with similar symptoms), should be identified[4]

. A history of other conditions should be taken to identify underlying skin conditions that may also need treatment or immunosuppression that may put the patient at greater risk of complications[4]

.

Further investigations are usually not required unless the infection is recurrent, persistent or widespread. If impetigo is recurrent, swabs for culture and sensitivity should be considered[2]

.

Alternative diagnoses, such as herpes zoster infection (shingles), eczema, chickenpox or molluscum contagiosum, should be considered in recurrent cases or those not responding to treatment[4],[10]

.

Complications

Infection may progress to more serious complications, such as deep soft tissue infections (cellulitis or osteomyelitis), glomerulonephritis and septicaemia[4]

. As with all suspected infections, pharmacists should be aware of signs of sepsis (such as confusion, tachypnoea, tachycardia, pyrexia, hypotension, cold and clammy skin, vomiting and diarrhoea) and the importance of urgent referral to hospital for urgent treatment.

If the skin is red, hot and painful, then cellulitis should be suspected[11],[12]

. Patients with suspected periorbital/orbital cellulitis (i.e. infection around or in the eye) should be referred to secondary care[12]

. If symptoms are rapidly worsening, this could be a sign of necrotising fasciitis and urgent review in an emergency department is advised[4]

.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a serious complication of impetigo, where a toxin released by Staphylococc us bacteria causes damage to the skin, resulting in painful extensive blistering and the top layer of skin to peel off (see Figure 1)[3]

. Specialist care is required for effective management, as patients will need intravenous antibiotics[3]

.

Figure 1: A baby aged two months with staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Source: DermPics/Science Source/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Although impetigo will usually resolve without scarring, scarring can occur; especially if the lesion is scratched, which should be advised against. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur and is more common in those with darker skin pigmentation[6]

.

Guttate psoriasis is a self-limiting, non-infectious skin condition that may develop after an impetigo infection[3]

. Small, scaly papules develop on the chest and limbs. This is more commonly seen in young patients.

Management

Effective management relies on ensuring that behaviours are adopted that help minimise the chance of spread and aid recovery, alongside pharmacotherapy to decrease recovery time or manage complications.

Pharmacological management

Management is typically completed with either topical or systemic therapy. Oral therapy is typically reserved for patients who show signs of systemic infection.

Topical treatment

Topical therapy should be used in localised non-bullous impetigo[2]

. The topical agent is applied after removal of the infected crusts with soap and water. The disadvantages of topical treatment are that application may be difficult if lesions are particularly widespread and it cannot eradicate organisms from the respiratory tract.

Hydrogen peroxide 1% cream (applied two to three times daily for five days) is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as the first-line treatment for non-complicated, non-bullous impetigo[2]

,[4]

. Hydrogen peroxide is as effective as using a topical antibiotic and adverse effects, such as irritation and skin bleaching, are minimal, as well as a low incidence of development of resistance compared with topical antibiotics[2]

.

Fusidic acid 2% cream (applied three times daily for five days) may be used if hydrogen peroxide is ineffective or unsuitable (e.g. if lesions are around the eyes)[2],[13]

. This may be supplied against a local Patient Group Direction by community pharmacists for the treatment of impetigo in children aged two and over[14]

. It is important to note that high resistance rates have been reported with the use of fusidic acid and its use should therefore be restricted[2]

.

Mupirocin 2% cream (applied three times a day for five days) is recommended if fusidic acid resistance is suspected or confirmed[4]

.

For all three treatments, the duration may be extended to seven days if considered necessary in more widespread infection; however, topical fusidic acid should not be used for longer than ten days to avoid the development of sensitisation and resistance[13]

.

It is important to remind patients to wash their hands before and after applying cream or ointment, and to complete the course prescribed even after symptoms improve. Emphasise the need to continue using the treatment for the prescribed course, even if infection appears to have cleared.

Systemic antibiotic treatment

These are required with systemic infection; for example, patients with swollen lymph nodes and glands, fever and diarrhoea[4]

. Oral antibiotics with gram-positive bacterial cover are indicated in systemic infection, infections that are widespread (e.g. bullous impetigo), complicated (as above) or recurrent[2],[4]

. As impetigo is highly contagious, advise patients to call their GP first as a face-to-face consultation may not be required and may help prevent spread. In addition, if a patient presents in the pharmacy, explain to them that it is contagious and they should adopt appropriate general hygiene practices and avoid visiting the pharmacy or GP. After the consultation, the pharmacy team should follow general hygiene advice of handwashing and wiping down surfaces the patient has touched.

An appropriate choice of oral antibiotics would be flucloxacillin, or a macrolide (e.g. clarithromycin or erythromycin) in penicillin-allergic patients[2],[4]

. A short treatment course of five days is usually sufficient[2]

. The length of the course can be increased to seven days if required, based on clinical judgement, and depending on the severity and number of lesions[2]

.

If symptoms have not resolved, or have worsened, within seven days, then the patient should be reassessed to rule out differential diagnoses, as listed above.

Any recent antimicrobial therapy that the patient may have received should be considered before prescribing topical or oral antibiotic therapy. A combination of oral and topical antibiotics should be avoided because of the risk of development of resistance[2]

.

If the infection is recurrent and MRSA is identified following a nasal swab, advice should be sought from local microbiology as treatment will depend on local resistance patterns[2]

. Mupirocin nasal ointment or neomycin nasal cream may be prescribed as a MRSA suppression treatment. Ensure that the patient does not have an allergy to peanut oil when supplying neomycin cream. Members of the same household may also be swabbed to identify and eliminate carriers and reinfections[7]

.

Non-pharmaceutical advice

Patients and their parents/carers should be advised of hygiene measures that will aid healing and reduce the spread to other parts of the body, prevent secondary infection and reduce spread to others. Pharmacists should advise patients to:

- Wash hands regularly, particularly after touching an affected area;

- Not to share topical treatment (if multiple members of the same family are infected, then ensure cream is provided for each patient);

- Not touch, scratch or pick at lesions as this can help avoid scarring;

- Avoid close contact with children, those with diabetes or those who are immunocompromised;

- Stay away from school, childcare facilities or work until lesions are healed, dry and crusted over, or 48 hours after initiation of antibiotic treatment because of the highly contagious nature of the infection;

- Not go to the gym or play contact sports;

- Keep sores and blisters clean and dry — advise them to cover these in loose clothing of gauze bandages (this may be more difficult for lesions on the face) and to bathe lesions in warm water before applying creams to remove crusting where possible;

- Not share face cloths, towels or other personal care products to prevent infection. In addition, explain it is necessary to wash face cloths, sheets and towels at a high temperature to kill bacteria. To prevent the spread in children, toys should be washed with detergent and warm water;

- Not preparing food for other people if they are infected. Explain that food handlers are required by law to inform employers immediately if they have impetigo;

- Cut children’s nails to prevent damage to infected sites and secondary infection.

- Ensure optimal treatment of any pre-existing skin conditions (e.g. eczema, head lice, scabies or insect bites)[2],[3],[4],[8]

.

Case studies

Case study 1: a five-year-old with a face rash

Consultation

A father comes into the pharmacy concerned about an itchy rash on his five-year-old’s face. On examination, you see that the child has small red sores about 1cm across around the mouth and nose and yellow crusting where these have burst. The father is worried that the child has chickenpox and asks whether it may be contagious to his child who is aeged 18 months.

Diagnosis

Due to the itchiness, crusting and location of the rash, non-bullous impetigo is suspected. Further questioning about duration and location reveals that the sores developed three days ago and are only present around this area.

After asking why he suspected chickenpox, he explains that the child had chickenpox last year and thought he may have it again. You explain that this does not recur and once someone has chickenpox it does not return. Further questioning reveals that the child has no other conditions and is not immunocompromised.

Advice and recommendations

Supply fusidic acid 2% cream via the pharmacy’s Patient Group Direction (PGD). Explain to the patient to use this three times per day for five days, even if symptoms appear to clear. In addition, advise that the child should be kept out of school until 48 hours after first using the antibiotic cream.

As to the father’s concerns around spreading of the infection, explain the importance of hand hygiene for the whole household, avoiding sharing towels or face cloths, cleaning toys with soap and water, and washing towels at a high temperature. The child’s nails should be cut short to avoid scratching of lesions. Advise that the child should be isolated from the younger sibling, where possible, while still infectious, and if the younger child develops similar symptoms, they will need to contact their GP for a prescription as they are under two years of age and not suitable for treatment under the PGD. Emphasise that even if there is some cream left from the first child’s infection, this should not be used as there is a risk of spreading the infection.

Case study 2: a teenager presents with a dry, cracked rash

Consultation

A patient aged 15 years asks for advice for what they have described as a bad eczema flare. They have a background of Crohn’s disease, for which they are currently taking a reducing course of prednisolone following a recent flare.

Diagnosis

On examination, the infection appears to be characteristic of non-bullous impetigo owing to the appearance of red lesions with crusting. The skin is very dry and cracked, and you suspect that bacteria has entered broken skin and caused the infection. The infection is limited to this site and the surrounding area is not swollen or hot. The patient is otherwise well with no fever.

Advice and recommendations

The patient is immunosuppressed because of their corticosteroid use and, as such, is at high risk of complications. Therefore, referral to their GP for oral antibiotics treatment is appropriate, as per NICE advice[2]

. The patient has no known drug allergies, so a prescription of flucloxacillin 500mg four times daily for five days would be reasonable.

Explain to the patient that eczema and the recent steroid course are risk factors for developing impetigo. Encourage them to discuss the management of their eczema with their GP to help manage flares and prevent future secondary infections. Advise the patient to keep eczema sites clean and well moisturised, particularly if taking steroids that may make them more susceptible to infection

Case study 3: an infant has developed a rash after possible contact with a child with molluscum contagiosum

Consultation

A mother asks you to examine a rash her one-year-old has developed on her tummy a couple of days ago. A friend’s child was recently diagnosed with molluscum contagiosum and she thinks that this may be similar.

Diagnosis

While it may be possible that if the children had been in contact with each other, the virus may have been transmitted, but the presence of fluid-filled vesicles on the abdomen of the child, rather than in flexures, appears to be more likely a case of bullous impetigo. The characteristic dimple seen in molluscum contagiosum papules is not visible and some blisters have burst to form yellow crusting. This form of impetigo is more common in children aged under two years.

Advice and recommendation

Bullous impetigo should be treated with oral antibiotics. Refer the mother to the GP to prescribe antibiotics and rule out other differential diagnoses. Advise the mother to call the surgery and explain that impetigo is suspected because of its contagious nature. The GP will likely prescribe a five-day course of oral flucloxacillin liquid. As systemic infection is more common with this form of impetigo and can be serious in young children, advise the mother to look out for a raised temperature, cold and clammy skin, irritability or sleepiness.

Preet Panesar is the lead antimicrobial pharmacist and Emily Green is a rotational pharmacist, both at University College London Foundation Hospitals.

Contact: preet.panesar@nhs.net; emily.green15@nhs.net

References

[1] Elliot AJ, Cross KW, Smith GE et al. The association between impetigo, insect bites and air temperature: a retrospective 5-year study (1999–2003) using morbidity data collected from a sentinel general practice network database. Fam Pract 2006;23(5):490–496. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml042

[2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Impetigo: antimicrobial prescribing. NICE guideline [NG153]. 2020. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng153 (accessed September 2020)

[3] NHS Inform. Impetigo. 2020. Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/infections-and-poisoning/impetigo (accessed September 2020)

[4] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Impetigo. Clinical Knowledge Summary. 2020. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/impetigo (accessed September 2020)

[5] Vashi NA & Kundu RV. Facial hyperpigmentation: causes and treatment. Br J Dermatol 2013;169(S3):41–56. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12536

[6] Davis EC & Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2010;3(7):20–31. PMID: 20725554

[7] Primary Care Dermatology Society. Impetigo. 2020. Available at: http://www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/impetigo (accessed September 2020)

[8] Public Health Agency. Guidance on infection control in schools and other childcare settings. 2017. Available at: https://www.publichealth.hscni.net/sites/default/files/Guidance_on_infection_control_in%20schools_poster.pdf (accessed September 2020)

[9] Public Health England. Health protection in schools and other childcare facilities. 2019. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-protection-in-schools-and-other-childcare-facilities (accessed September 2020)

[10] Sladden MJ & Johnston GA. Common skin infections in children. BMJ 2004;329:95–99. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7457.95

[11] NHS. Impetigo. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/impetigo (accessed September 2020)

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cellulitis – acute. Clinical Knowledge Summary. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cellulitis-acute (accessed September 2020)

[13] BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online). Available at: http://www.medicinescomplete.com (accessed September 2020)

[14] Electronic medicines compendium. Naseptin nasal cream. 2017. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5524/smpc#gref (accessed September 2020)