St Stephen's Hospital / Science Photo Library

In this article you will learn:

- The initial steps when managing a burn

- How to assess a burn’s severity

- Signs that may suggest a burn is non-accidental

Max Gordon, a 43-year-old man, was placing a baking tray into a preheated oven when his hand slipped. His forearm was pushed against the wall of the oven causing a burn. His wife calls the pharmacy for advice on what they should do.

Step one: initial action

A burn is an injury caused by thermal (heat), electrical, chemical or radiation energy. Scald is a term used to describe a burn injury caused by hot liquid or steam[1]

. For the purposes of this article, the term burn refers to both burn and scald.

For all burns, basic first aid should be carried out immediately. In most cases, a health professional will not be present when the burn is sustained. Anyone responding to a burn incident must first ensure his or her own personal safety, before checking the patient’s airways, breathing and circulation (i.e. the ABC of first aid). Patients should be stabilised before a burn is treated[1]

.

Initial action depends on the type of burn sustained.

Heat burns should be managed as soon as the person is separated from source of heat (if safe to do so). Clothing should be removed, but material that has become stuck to the skin should not be peeled off. Flames, if present, should be doused with a wet cloth[1]

.

Irrigate (i.e. wash with a continuous flow of water) the burn with tap water for 20–30 minutes. Avoid using ice-cold water to irrigate the burn: cold temperatures can precipitate vasoconstriction and slow the healing process[1].

Patients should be kept warm. Children and the elderly are particularly susceptible to hypothermia; the mechanism for this is unknown, but it is not caused by shock or burn and is likely to be a result of the higher body surface to weight ratio in children, and impaired thermoregulation in the elderly.

Cover the burn with cling film (plastic bags can be used if the hands have been injured). Layer the cling film on the burn (enough to provide a barrier but the burn is still visible without removing the film), but avoid wrapping a burnt limb circumferentially (all the way around the limb).

Electrical burns should be managed only after the patient is separated from the source of electricity. If possible, isolate the source of electricity (e.g. turn off the mains power). Attempt a rescue if the source of electricity is of low domestic voltage (e.g. 110–240 volts), using a non-conductible object (e.g. a wooden stick or wooden chair) to separate them from the current. Do not attempt to rescue someone who is connected to 1,000 volts or more (e.g. electrical train lines) because the risk of conduction is very high[1]

.

Electrical burns are usually deep and an ambulance should be called immediately.

Chemical burns require irrigation and cooling for one hour by running the burn under a tap (irrigation with sodium solution is used for cleaning only). Identify the chemical that has caused the burn; different types of chemical will produce different burns.

Chemical burns are usually deep[1]

and an ambulance should be called immediately.

Step two: assessment

Max has sustained a heat burn. He immediately moved his forearm off the heat source (the wall of the oven). He had been holding his arm under a running tap for five minutes when his wife called the pharmacy. The pharmacist advises him to hold it under the running water for another 20–25 minutes and to seek medical attention so that the severity of his burn can be assessed by a health professional.

All burns should be assessed by a clinician competent to do so; if there is doubt, the patient should be referred to accident and emergency (A&E). Most burns can be classified as minor or major. Most minor burns can be treated in primary care, whereas major burns need to be referred to specialist secondary care units, such as a regional burns unit or a burn centre that provides 24-hour advanced burn care[2]

.

The main criteria for assessing a burn can be remembered using the mnemonic ASDA:

- Age of patient

- Site of burn

- Depth of burn

- Area of burn; burn surface area (BSA) expressed in terms of percentage of total body surface area (TBSA).

Other non-burn related factors to consider include the presence of any pre-existing comorbidities and other injuries sustained during the incident. Non-accidental injuries (see ‘Non-accidental injuries’) and the patient’s social situation are also important factors to take into account.

Age, together with the area of burn (see below), determines if referral to the local hospital’s A&E department is warranted. Referral should be considered for children under five years of age and adults over 60 years of age.

The site of the burn is an important factor in referral. Burns to the face, hands, feet, genitalia, flexures and axillae (armpits) should be referred to A&E. The risk of complications — such as cosmetic, loss of movement, loss of function and infection — are high with burns to these sites of the body, hence the need for special care. Burns to these areas must be referred regardless of how deep the burn is[1],[2]

.

There may be local arrangements in place for referring patients straight to a regional burns unit rather than via A&E[1]

. Pharmacists in England can find out about these by contacting their local clinical commissioning group (CCG).

Depth of burn is now classified as:

- Superficial

- Partial thickness-superficial

- Partial thickness-deep dermal

- Full thickness

The older classification system described the depth of a burn as first, second, third or fourth degree. Deep partial thickness and full thickness are classified as major burns. The depth of a burn can be hard to classify, and this should only be done by experienced clinicians (see ‘Different skin depths of human burns’)[2]

.

| Table 1: Different skin depths of human burns | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Type of burn | Older classification | Layer affected | Examination |

Superficial

| First degree | Epidermis only, dermis intact (similar to sunburn) | Simple erythema. Skin appears red, painful and there is no blistering. Capillary refill* (CR) — skin blanches and regains colour quickly. |

Partial thickness — superficial dermal

| Second degree | Whole epidermis and upper layers of dermis | Skin is pale pink. Blistering is present. CR — skin blanches and regains colour slowly. |

Partial thickness — deep dermal

| Third degree | Whole epidermis and deep layers of dermis | Skin is dry or moist and blotched or red. Can be blistered and painful but may not be. CR* — does not blanche. |

Full thickness

| Fourth degree | Epidermis and dermis layers are all affected. Extends to subcutaneous layers. | Skin dry and white, brown or black in colour. It is painless, looks leathery or waxy. CR* — does not blanche. |

*Capillary refill — this is usually performed by pressing on the skin with a finger. For burns patients, a sterile swab should be used to prevent introducing infection to the burn wound. | |||

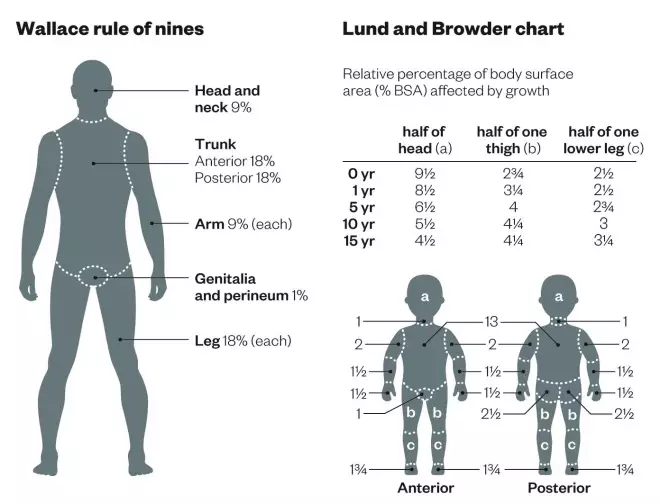

Area covered by burn can be determined in adults using the Wallace rule of nines or, in children, using the Lund and Browder chart (see ‘Wallace rules of nines with Lund and Browder chart’). Adults with more than 3% TBSA and children with more than 2% TBSA should be referred to A&E. People with circumferential burns should also be referred to A&E regardless of TBSA because the risk of losing the limb or limb function is high with circumferential burns[1],[3]

.

Wallace rules of nines with Lund and Browder chart

These two methods are used to determine the surface area covered by a burn; the Wallace rule of nines is used for adults and the Lund and Browder chart for children, as the percentage surface area changes as the child grows

Pre-existing comorbidities or conditions

can increase the risk of complications and prevent healing. People with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and those who are immunocompromised or pregnant should be referred to specialist care for management.

Other injuries, such as inhalation injuries, can be sustained during burn incidents. Pulmonary oedema (caused by irritation of lung tissue by inhaling a hot source) in the airways can be fatal. Signs that a person has sustained an inhalation injury include[1]

:

- Burns to the face, neck, or torso;

- Singed nasal hair;

- Carbonaceous sputum (i.e. sputum that is black or brown) or soot particles in oropharynx;

- A change in voice with hoarseness;

- Dyspnoea and stridor (breath sounds caused by a narrowed or obstructed airway);

- Erythema or swelling of oropharynx on examination.

Step three: management

Max is advised to visit an urgent care centre near his home to have his burn assessed. A blister that has formed on the affected area and the skin surrounding the burn is pink. The capillary refill check shows blanching with a return to normal within four seconds. Max also reports that the burn is causing him pain. It is determined that Max has a superficial burn of partial thickness depth. The area affected by the burn is calculated using the Wallace rule of nines and is found to be less than 2% TBSA. He has no pre-existing comorbidities and has sustained no other injuries.

For the management of minor burns, simple analgesics such as paracetamol or ibuprofen are suitable for pain relief. Consider codeine if the pain is severe or persists[1]

.

No topical creams are indicated for burns because there is inconclusive evidence to suggest they offer any benefit and they may impede accurate assessment of the burn[1]

.

Blisters should not be de-roofed or aspirated as doing so can be a cause of infection. Burn areas that restrict movement, or blisters that are large, may be aspirated using a sterile technique but de-roofing should be avoided[1]

.

A prophylactic tetanus vaccination should be considered for people at high risk of tetanus infection (e.g. burns that have been in contact with soil or people who have not had primary prophylaxis)[1]

.

Burn wounds should be cleaned with sodium chloride 0.9% solution before a primary non-adherent bandage is applied, such as Jelonet or Mepitel. A secondary bandage should then be applied to absorb any exudate. The social situation of the patient should also be considered when managing burns. People with no fixed abode may need special consideration because rough living conditions may impede healing, and analgesia and wound dressings may be difficult to manage in their living arrangements[1]

.

All major burns and red flags should be referred to A&E (and then specialist care) for treatment. These include[4]

:

- Burns covering more than 2% of TBSA for children (aged under 16 years);

- Burns covering more than 3% of TBSA for adults;

- Superficial burns to the face, neck, axillae, hands, genitalia, feet, and areas that could affect mobility;

- Deep dermal and full thickness burns;

- Superficial circumferential burns;

- Electrical, chemical, frictional or cold burns;

- Suspected non-accidental burn.

Patients who sustain major burns are at a higher risk of hypovolaemia, which can be managed with intravenous fluids. Intubation may be required for patients with inhalation injuries, such as oedema or obstruction of the airways.

Max is prescribed oral co-codamol 30mg/500mg tablets for pain relief. The burn is dressed with a primary dressing (Mepitel) and has a sterile dressing pad applied on top and affixed with surgical tape.

Step four: follow-up

The wound should be assessed after 24 hours and dressings should be changed every three to five days. The wound should be assessed for signs of infection (e.g. discharge, pallor, pain, stiffness, elevated temperature) at each dressing change. Infected burns can be treated with a seven-day course of oral flucloxacillin[1]

. Burns only require a microbiology culture for sensitivity testing if the infection does not respond to first-line and second-line antibiotics (e.g. co-amoxiclav).

Post-traumatic stress may affect some patients, especially those with major burns. Psychosocial support should be offered if necessary[2]

.

Max returns the next day for a review. His pain is under control, there are no signs of infection and he reports feeling well. He is asked to return in three days. After three days, the blister has burst and the skin is healing well with no signs of infection. He is advised to see his GP for review in five to seven days.

Non-accidental injuries

Non-accidental injuries need to be referred to a regional burns unit within 24 hours as they may be more severe. It also allows an experienced burns clinician to assess the burn and decide whether it really is non-accidental. In some cases, this could result in a child being taken into care. Clinicians will need to report these cases according to local safeguarding protocols. Signs of non-accidental injuries include[1],[3], [4],[5]

:

- Unusual or bizarre explanation of the cause of the burn;

- Burns in children who are not independently mobile;

- Injuries to areas that are unlikely to be in contact with a hot object, such as soles of the feet, backs of hands, the buttocks or back;

- Signs of forced immersion, such as scalds to the hands that resemble a glove or stocking, or symmetrical burns to the limbs. The “doughnut sign” (sparing of area in contact with bottom of bath) that suggests a person was held down with force is seen in non-accidental burns on children with immersion burns;

- Inconsistencies with the history of events leading to the burn, history of inadequate supervision of the child, poor compliance with healthcare services, such as no immunisations;

- Lack of guilt or lack of concern with regard to treatment;

- Inconsistencies between the reported age of burn and visual presentation;

- No splash marks for scald injuries;

- Signs of restraint on upper limbs.

Sam Akram is a senior lecturer in prescribing and Jan Lovelle is a registered general nurse and deputy head of the Department of Health, Social Care and Education, both at Anglia Ruskin University. Su Nambisan is a principal general practitioner at Chapel Street Practice in Walsall.

References

[1] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Burns and scalds. May 2013.

[2] British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons. Burns. Available at www.bapras.org.uk.

[3] NHS Choices. Map of Medicine: Burns. February 2014.

[4] Stockdale N. Clinical guidelines burn injury. Dudley: Russells Hall Hospital; 2012.

[5] Hettiaratchy S. Pathophysiology and types of burns. The BMJ 2004;328(7453):1427.