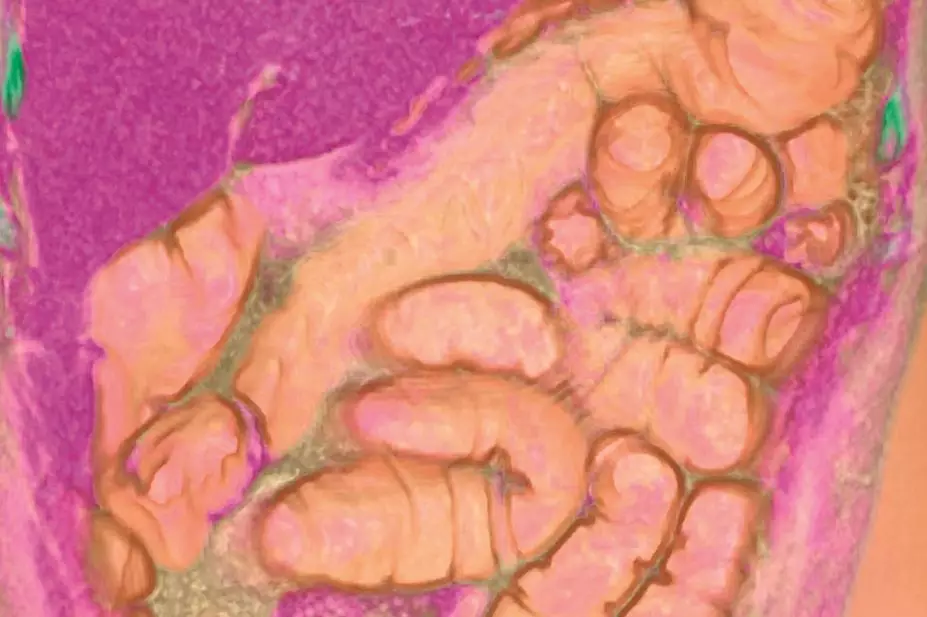

BSIP, Gondelon / Science Photo Library

In this article you will learn:

- The common medicines that may cause constipation

- The effect of different laxatives and when to use each option

- How to manage complications including faecal impaction

Constipation describes infrequency and difficulty when emptying the bowels. It can affect people of all ages, although it is more common in women; particularly those who are pregnant due to hormonal fluctuations. Older people — particularly those aged over 70 years — are also more likely to be affected by constipation because of several factors, including a more sedentary lifestyle, level of fluid intake, diet, and delaying the urge to defecate because of mobility issues.

For many people, constipation is transient in nature and easily treatable, but for others it can be a chronic condition causing substantial discomfort and pain[1],[2]

.

The prevalence of constipation in the UK is estimated at around 8.2% of the general population. However, the perception of constipation is widely variable, and 39% of men and 52% of women report straining when emptying their bowels in at least one in four occasions[3]

.

The incidence of constipation per year is five times higher in the elderly than in younger adults and is usually multifactorial since this population group is exposed to various risk factors for constipation, including medication (see Medicines known to cause constipation)[4],[5]

. Reduced appetite in the elderly can lead to poor diet with a reduction in fibre intake and decreased fluid intake causing hard stools that are difficult to pass. Reduced mobility is also a common risk factor in the elderly since this reduces gut motility and contributes to constipation and faecal impaction[5]

.

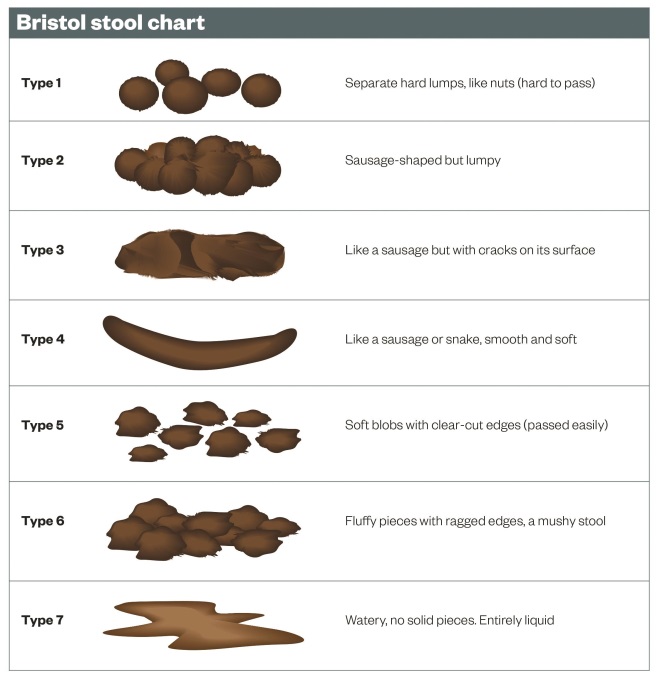

Typical symptoms of constipation include abdominal pain, cramping, bloating, nausea and straining during bowel movements[1],[2]

. Stools tend to be dry, hard and lumpy, and indicated as type 1 or 2 on the Bristol stool chart (also known as the Meyers scale)[6]

. The pain and discomfort from chronic constipation and the associated complications can impact on a person’s quality of life, particularly in the elderly.

Chronic constipation can be classified as functional (or idiopathic) or secondary constipation[1],[2]

. Functional constipation occurs without an anatomical or physiological known (e.g. because of poor diet). It is diagnosed by the exclusion of a pharmacological or medical cause.

Secondary constipation is caused by a drug or medical condition (see ‘Medicines known to cause constipation’). Conditions known to cause constipation include disorders that alter the functionality of the gastrointestinal tract, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Less obvious conditions include multiple sclerosis, diabetes, hypothyroidism and Parkinson’s disease because of reduced mobility, weight gain, or reduced food and fluid intake. Conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis can also have direct effects on the nerves that control bowel function, leading to a weakness and uncoordinated contraction of pelvic floor and abdominal muscles and preventing the passage of stools.

Medicines known to cause constipation

| Drug class | Management |

|---|---|

| [7]. Andrews CN & Storr M. The pathophysiology of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;25:16B–21B. | |

Antihypertensives Diuretics, clonidine, calcium channel blockers |

Switch (if clinically appropriate) to less constipating medicines such as beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin-II receptor antagonists. Diuretics can cause constipation because of less available fluid causing dry, hard stools. Therefore, laxatives such as docusate may be appropriate to act as a surfactant and softener, or osmotic laxatives can be used to increase the amount of water in the large bowel. |

Antidepressants Tricyclic antidepressants | Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and serotonin and noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors are alternatives less associated with constipation. |

Antimuscarinics procyclidine, oxybutynin |

Laxatives can be co-prescribed. The choice will depend on the pharmacodynamic mechanism causing the constipation. For example, anticholinergic agents (e.g. oxybutynin, procyclidine) decrease GI motility and therefore a stimulant laxative may be more appropriate. There is conflicting literature over whether laxatives should be used regularly in patients with Parkinson’s disease, and the decision whether to use laxatives should be made on an individual patient basis after considering the risks and benefits. |

Antiparkinsonian medicines levodopa, dopamine agonists, amantadine | |

Iron supplements | Intravenous iron could be used, or a laxative may be co-prescribed. |

Aluminium-containing agents Sucralfate and antacids | Replace with proton pump inhibitors. |

Analgesia Opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Opioids cause constipation by decreasing peristalsis and by enhancing the resorption of fluid and electrolytes[8] Use the lowest effective dose and co-prescribe a stimulant laxative (e.g. senna). |

Assessment

Constipation is usually diagnosed if a patient reports a reduced frequency of bowel movements, typically less than three bowel movements in one week[4]

. This is not definitive, and the patient should also be asked about the frequency and character of any stools, and when constipation first presented. A physical or internal rectal examination may also be performed, which may confirm that faecal masses are palpable abdominally or perianally[2]

.

When assessing a patient for constipation, it is important to consider possible causes, such as medication and comorbidities. It is also important to check for red flag symptoms such as unexplained weight loss, rectal bleeding, a family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, or signs of obstruction[2]

. Patients with any red flag symptoms should be referred to a specialist for further investigation.

The Rome III diagnostic criteria can be used to classify functional gastrointestinal disorders, and may be useful when functional constipation is suspected and contributing medicines or medical conditions have been excluded[9]

.

Using the Rome III diagnostic criteria, constipation may be diagnosed if patients who do not take laxatives report at least two of the following in any three-month period during the previous six months:

- Straining in at least 25% of bowel motions;

- Lumpy or hard stools in at least 25% of bowel motions;

- Sensation of incomplete evacuation in at least 25% of bowel motions;

- Sensation of anorectal blockage in at least 25% of bowel motions;

- Manual manoeuvres have been required to facilitate at least 25% of bowel motions (e.g. digital evacuation);

- Fewer than three bowel movements per week;

- Loose stools are not present, and there are insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome[9]

.

Treatment

It is important to consider the primary cause when treating constipation. In many cases, constipation may be a result of poor diet and lack of exercise, and therefore patients should be encouraged to increase the fibre in their diet and fluid intake before trying laxatives.

Fibre increases the bulk and plasticity of stools, which in turn promotes propulsive activity and movement through the colon, thus preventing constipation[3]

. Good sources of fibre can come from pulses, such as beans, chickpeas and lentils, as well as wholegrain bread, rice and pasta, nuts and dried fruit. Typically, patients should be warned to avoid caffeine containing products since they can contribute to constipation through dehydration. Low-fibre or high-fat foods, such as dairy products and eggs, can slow down digestion and therefore cause constipation.

There is little evidence that exercise can also increase gut motility. However, one study found that women who reported physical activity of once a week or more were significantly less likely to report constipation[10]

.

Although improved diet and exercise may relieve acute constipation, many patients require pharmacological treatment. In 2010, the then-NHS Information Centre (now the Health & Social Care Information Centre) reported that 15.9 million prescriptions were dispensed in the community in England for laxatives, at a cost of £70.6m[11]

; this did not include laxatives purchased over the counter. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended that clinicians review the prescribing of laxatives for adults and ensure they are limited to the short‑term treatment of constipation in circumstances when dietary and lifestyle measures have proven unsuccessful or if there is an immediate clinical need[12]

.

There are many different classes of laxatives with differing modes of action; as such, a combination of laxatives is usually employed to maximise efficacy.

Stimulant laxatives (e.g. senna, bisacodyl) improve intestinal motility via muscle contractions and reduce water loss from the faeces, softening the stool. A potential side effect of stimulant laxatives is abdominal cramping (caused by the increased intestinal motility).

Faecal softeners (e.g. docusate) stimulate peristalsis by increasing faecal mass; they act to lower surface tension and allow water and fats to penetrate hard, dry faeces.

Co-danthromer and co-danthrusate are combination products containing the stimulant laxative dantron and a stool softening agent (poloxamer ‘188’ and docusate, respectively). Dantron-containing products must only be used in terminally ill patients because it may be carcinogenic[13]

.

Opioid-induced constipation

Stimulant laxatives are the treatment of choice for opioid-induced constipation because their mode of action counters the constipating action of opioids. If patients with opioid-induced constipation do not achieve adequate results after three to four days of taking a stimulant laxative, a faecal softener should be added. Osmotic laxatives are also effective for opioid-induced constipation and can be better tolerated than stimulant laxatives which can cause abdominal cramping.

Methylnaltrexone is an alternative treatment option, given by subcutaneous injection, if conventional laxatives are ineffective. It acts as an opioid-receptor antagonist without altering the central analgesic effect of opioids[13]

. Methylnaltrexone is licensed for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in palliative care, where it can be used as an adjunct to laxative therapy.

Bulk-forming laxatives (e.g. ispaghula husk, methylcellulose) treat constipation by increasing faecal mass through water binding to stimulate peristalsis[13]

. This class of laxatives usually takes a couple of days to achieve full effect.

Osmotic laxatives (e.g. macrogols, lactulose) increase the amount of water in the large bowel, either by drawing fluid from elsewhere in the body or retaining the fluid consumed with the medicine[13]

. Patients may feel dehydrated when using this class of laxatives; this can be avoided by drinking fluids when taking the laxative.

Enemas are another option for the treatment of constipation, particularly for patients unable to take oral laxatives. Enemas containing arachis oil (ground-nut oil, peanut oil) lubricate and soften impacted faeces to encourage a bowel movement, although they are contraindicated in patients with nut allergies. Phosphate enemas and sodium citrate enemas are also used when bowel clearance is required rapidly (e.g. before radiology, endoscopy or surgery).

Prucalopride was licensed by the European Medicines Agency in 2009 as a treatment option for women in whom laxatives fail to provide adequate relief[14]

. Prucalopride is a selective serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonist that stimulates colonic motility and accelerates gastric emptying[15]

. The efficacy and safety profile of the medicine has not been investigated fully in men, and therefore its licence is limited to women. It is contraindicated in patients with intestinal perforation or obstruction, and those with severe inflammatory bowel conditions including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis[15]

.

Lubiprostone is a novel medicine licensed for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation as a two-week treatment course; alternative treatment should be sought if there is no response after two weeks. Studies have found lubiprostone to be well tolerated in up to a year of treatment[16]

. Its mechanism of action involves the activation of chloride channels, increasing intestinal fluid secretion and thus facilitating intestinal motility[17]

.

Complications

Faecal impaction can occur in patients with untreated constipation. This is when dried, hard stools collect in the rectum, causing an obstruction and making it difficult for stools to pass naturally. The accumulation of stools unable to pass increases the pressure against the muscles in the rectum, causing them to weaken[1],[10]

. This reduction in muscle tone can lead to overflow incontinence, where watery stools leak around the impacted hard stools.

Faecal impaction is painful and can be distressing for patients, who may remain housebound because of the fear of incontinence in public areas. It is very unlikely for patients to pass the stools naturally if impacted; treatment usually starts with a high dose osmotic laxative. If inadequate response is achieved through oral laxatives, a bisacodyl suppository or sodium citrate enema can be used (see below for case study regarding faecal impaction). It could take several months for colorectal tone to be restored and some patients are given exercises to help accelerate the healing process.

Case study: faecal impaction

Patient details: 79-year-old male care home resident with increased confusion over the past two weeks. His appetite is reduced and he has been less mobile since recovering from surgery a month ago.

Past medical history: Alzheimer’s disease, osteoarthritis, fractured neck of femur and subsequent hip replacement one month ago.

Drug history: galantamine 12mg twice daily, Adcal D3 twice daily, alendronic acid 70mg once weekly on Sundays, paracetamol 1g four times a day, codeine 30mg four times a day (acutely started post op).

Presenting complaint: One week history of faecal and urinary incontinence, including the passing of watery stools. Patient reports the leaking of stools from coughing. He also complains of bloating, cramping and abdominal pain. Care home staff report that he is more confused and agitated that normal.

On examination: Tender, distended abdominal area. Evidence of intestinal mass on palpation. Digital rectal examination confirms the presence of dry, hard stools indicating impaction.

Treatment day 1: Osmotic laxative (macrogol) started.

- Why this choice of laxative? The primary goal is to hydrate and soften the stool. Laxatives that work by stimulating the bowel or cause cramping should be avoided to reduce further damage to the bowel. Faecal softeners such as docusate can be used to help soften stool higher in the colon.

Treatment day 3: Symptoms have not improved and an enema is prescribed.

- Why is an enema used? The time of effect is more predictable than with oral laxatives. More localised mode of action if stools impacted at base of rectum.

- Which one is preferable? Sodium citrate enema or phosphate enema are both osmotic enemas that are useful for the removal of hard, impacted stools. They act within 5–15 minutes for a more immediate effect; however, if impacted stools are particularly large, this does not allow enough time for faecal mass to soften adequately to be expelled. Arachis oil enema can therefore be used in this case.

The care home staff should be advised to increase the patient’s dietary fibre. Regular physiotherapy visits to the home are required to encourage movement following hip replacement surgery. The dose of codeine should be reduced as this can contribute to constipation. Laxatives should be continued while the patient is still immobile following his hip operation (for review in one to two weeks, once mobility has improved).

Haemorrhoids are areas of swelling containing enlarged blood vessels around the anus, caused by increased pressure in the blood vessels as a result of straining while defecating. Haemorrhoids can cause bleeding after the passing of stools and can be itchy; they are usually relatively simple to treat with a short course of topical product containing corticosteroids and a local anaesthetic[13]

.

In severe cases, laser therapy or banding ligation may be used. Banding ligation involves tying elastic bands tightly around each haemorrhoid, restricting the blood supply and causing them to detach[12]

. Surgery may be required to remove haemorrhoids if these treatments are ineffective.

Rectal prolapse is a more serious complication of repeated straining during bowel movements, which involves a protrusion of the lower intestine through the anus. This is treated surgically[1]

.

Anal fissures are a possible complication of constipation, where the forced passage of hard stools causes small tears through the lining of the anal canal. Patients experience a burning pain and may notice bleeding following bowel motions. Anal fissures are usually self-limiting and heal without the need for medical intervention. However, topical glyceryl trinitrate ointment can relieve the associated pain by the release of nitric oxide, which mediates the relaxation of the internal anal sphincter, thus reducing anal pressure and improving blood flow.

Alternatively, a topical anaesthetic such as lidocaine can be applied before a bowel motion. Once healed, patients may be required to take laxatives or increase their dietary fibre intake to prevent recurrence[13]

.

Emma McClay is a specialist pharmacist in gastroenterology at Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust.

References

[1] NHS Choices. Constipation 2014.

[2] National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Constipation 2015.

[3] Mueller-Lissner SA, Wald A. Constipation in adults. BMJ Clin Evid 2010.

[4] World Gastroenterology Organisation. Constipation: a global perspective. Milwaukee: WGO 2010.

[5] Gallagher P & O’Mahony D. Constipation in old age. Best practice & research. Clin Gastroenterol 2009;23:875–887.

[6] Lewis SJ & Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:920–924.

[7] Andrews CN & Storr M. The pathophysiology of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;25:16B–21B.

[8] Kurz A & Sessler D. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: pathophysiology and potential new therapies. Drugs 2003;63:649–671.

[9] Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999;45.

[10] Dukas L, Willett WC & Giovannucci EL. Association between physical activity, fiber intake, and other lifestyle variables and constipation in a study of women. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1790–1796.

[11] NHS Information Centre. Prescriptions dispensed in the community: England, statistics for 2000 to 2010 Health and Social Care Information Centre. London: NHSIC 2011.

[12] Giamundo SR, Geraci M, Tibaldi L et al. The hemorrhoid laser procedure technique vs rubber band ligation: a randomized trial comparing 2 mini-invasive treatments for second- and third-degree hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54: 693–698.

[13] British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society. British National Formulary. London: RPS 2014.

[14] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Prucalopride for the treatment of chronic constipation in women. London: NICE 2010.

[15] Shire Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Summary of Product Characteristics: Prucalopride (Resolor). 2014.

[16] Sucampo Pharma Europe Ltd. Summary of Product Characteristics: Lubiprostone (Amitiza). 2013.

[17] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lubiprostone for treating chronic idiopathic constipation. London: NICE 2014.