Shutterstock.com

Endometriosis can be a chronic and debilitating condition. It is often difficult to diagnose, taking an average of 7.5 years for a complete diagnosis to be made, owing to the non-specificity of presenting symptoms[1]

. This delay can result in decreased quality of life for patients. Healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, have an important role to play in identifying the signs and symptoms of endometriosis to support diagnosis at the earliest possible opportunity.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists defines endometriosis as “the growth of endometrial-like tissue (the womb lining) outside the uterus (womb)”[1]

. In the UK, it is estimated that endometriosis affects 10% of women from their first menstrual period to menopause and it is the second most common gynaecological condition after fibroids[1]

. Any woman of reproductive age, regardless of race or ethnicity, can be affected by the condition[2]

.

This article will describe the diagnosis and management of endometriosis, as well as the referral process.

Signs and symptoms

Endometriosis can be difficult to diagnose, not only because of the wide variety of symptoms and their different presentations (see Box 1), but also because of the non-specific nature of presenting symptoms (e.g. general malaise and sleep disturbance)[3]

.

Box 1: Signs and symptoms of endometriosis

Endometriosis should be considered when women of any age present with one or more of the following symptoms:

- Chronic pelvic pain (≥6 months);

- Dysmenorrhoea (that affects quality of life);

- Hormonal/cyclical gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. painful bowel movements, bleeding);

- Urinary symptoms (e.g. haematuria, pain passing urine);

- Pain during or after sexual intercourse;

- Fatigue;

- Depression;

- Infertility/subfertility (when associated with ≥1 of the symptoms above).

Sources: Endometriosis UK[2],[5]

; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[4],[6],[7]

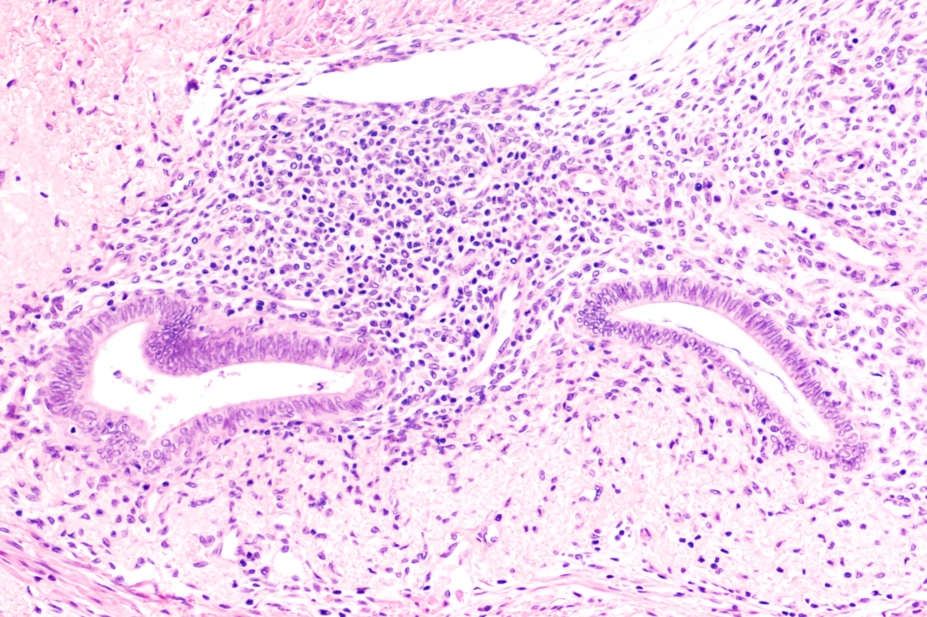

Pathophysiology

Although it is well recognised that endometriosis is mediated by cyclical hormonal fluctuations, the exact pathophysiology is not fully understood[8]

. The monthly hormonal changes that normally cause proliferation of the endometrium also cause the ectopic endometrial cells (endometriosis) to proliferate, resulting in inflammation, pain and adhesions (scar tissue formation)[2]

.

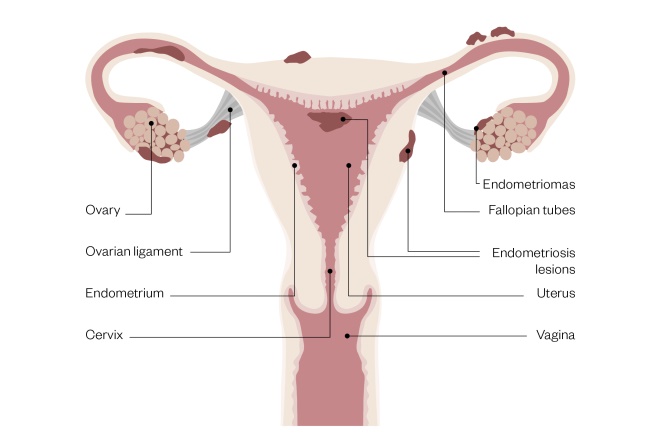

Most of the ectopic endometrial-like tissue deposits in the pelvis. Endometriomas (ovarian cysts) may also develop when the ovaries are affected (see Figure)[4]

.

Figure 1: Female reproductive system with signs of endometriosis

Source: Rich Lee

Aetiology

The aetiology of endometriosis is not fully understood; however, there are several potential causes:

- Retrograde menstruation — the backwards flow of menstrual debris through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity — leads to the possible implantation of refluxed endometrial tissue outside the uterus[9],[10],[11],[14]

. - Metaplasia (an abnormal change in the tissue, i.e. cells in the pelvis differentiating into endometrial cells) has also been proposed. Alternatively, lymphatic or vascular spread of the endometrial cells may occur;

- Immune dysfunction, or altered immune-surveillance, which may allow the proliferation of endometriosis (i.e. the patient’s immune system does not repress endometriosis)[5]

.

Patients may also have a genetic predisposition because familial clusters of endometriosis have been demonstrated in several studies; however, some have shown that any potential inheritance mechanism does not fit the Mendelian model of inheritance (i.e. where any hereditary component is likely to be polygenic in nature)[12]

. Further research is ongoing to identify specific gene groups that may be implicated that may also form potential drug targets[13]

.

Risk factors

There are several risk factors that may increase the chance of developing endometriosis. These include, but are not limited to:

- Having a first-degree relative with the disorder (e.g. mother, sister, daughter);

- Primigravida (being pregnant for the first time) above the age of 30 years;

- Ethnicity — Caucasian women are thought to be at a greater risk of developing endometriosis;

- Anatomical abnormalities (e.g. women with an abnormal uterus or fallopian tubes);

- Menstrual cycle factors (e.g. early age of first menstrual period, dysmenorrhoea, short menstrual cycle [i.e. less than 27 days], long periods [i.e. more than 7 days]);

- Allergies (e.g. food, eczema, hay fever);

- Obesity;

- Exposure to toxins — research suggests that dioxins may contribute to the development of endometriosis[8],[14],[15]

.

Diagnosis

While there are several procedures that can be used to aid the diagnosis of endometriosis (see Table 1), the only definitive way to confirm it is to carry out a full, systematic laparoscopy[15]

. If the results are normal, endometriosis can be excluded and alternative symptom management should be offered[6]

.

| Diagnostic test/procedure | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[6] | |

| Ultrasound | Should be performed to identify endometriomas and deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder or ureter. A transvaginal ultrasound should be considered even if a pelvic and/or abdominal exam is normal; however, if this is inappropriate, a transabdominal ultrasound of the pelvis should be considered. |

| MRI | A pelvic MRI is a secondary investigative tool to assess the extent of deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder or ureter. |

| Laparoscopy | A diagnostic laparoscopy should be performed in women with suspected endometriosis, even if the ultrasound was normal. During a diagnostic laparoscopy:

|

| Physical examination | Pelvic examinations can help identify abdominal masses and pelvic signs (e.g. reduced organ mobility and enlargement, tender nodularity in the posterior vaginal fornix and visible endometriotic lesions). An abdominal examination can exclude abdominal masses if a pelvic examination is not appropriate. |

While serum cancer antigen 125 (CA125) should not be used to diagnose endometriosis, raised levels (≥35IU/mL) may be consistent with having endometriosis[6]

. Elevated CA125 can also be indicative of malignancy[6]

.

Women are most commonly diagnosed with endometriosis between the ages of 30 years and 40 years[4]

. Although endometriosis is uncommon among women aged 20 years and younger, it should not be excluded[6]

. Endometriosis should also not be excluded in women who have returned a normal abdominal or pelvic examination, ultrasound or MRI[4],[6]

. A pelvic examination is unlikely to be abnormal because most cases of endometriosis are usually mild to moderate in severity[4]

.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) also recommends that the patient should keep a pain and symptom diary to aid discussions about suspected or confirmed endometriosis[6]

.

Differential diagnosis

The symptoms of endometriosis can be indistinguishable from other conditions, including:

- Pelvic adhesions, functional or neoplastic ovarian cyst, adenomyosis and uterine fibroids;

- Malignancy (e.g. colorectal, ovarian, cervical or bladder cancer);

- Dysmenorrhoea, ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion, uterine malformation;

- Irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic constipation;

- Appendicitis, cystitis, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, serositis;

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs), chlamydia, gonorrhoea;

- Degenerative disc disease and congenital abnormalities of the reproductive tract (e.g. hemivagina, vaginal septum)[4]

,[8]

.

A full blood count may rule out infection and inflammation, and may distinguish pelvic inflammatory disease from endometriosis. Urinalysis, urine culture and blood serology can rule out UTIs and sexually transmitted infections (STIs)[8]

.

Pharmacological management

The treatment choice for endometriosis depends on the individual patient’s needs and preferences, such as their age and whether they wish to conceive (see Table 2)[4]

.

Analgesia

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, naproxen and mefenamic acid, should be offered unless contraindicated.

NSAIDS inhibit the synthesis of prostaglandins via cyclo-oxygenase and should be commenced prior to pain or menstrual onset[16]

. Prostaglandins have been implicated in the modulation of pain response, inflammation, dysmenorrhoea and menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding)[17]

.

Ibuprofen has a licensed indication for dysmenorrhoea in women of all ages and has a relatively superior gastrointestinal (GI) safety profile[4]

. Naproxen is licensed for patients aged 16 years and over, and is associated with an intermediate risk of GI side effects. While mefenamic acid is licensed for the treatment of dysmenorrhoea, there are concerns about its narrow therapeutic window and its propensity to cause seizures in overdose[4]

. For example, a woman weighing 50kg would only need to ingest an extra 500mg dose in 24 hours (total 2,000mg) for her to be considered at risk of toxicity[4]

.

Paracetamol should be given when NSAIDs are contraindicated or in addition to an NSAID when treatment response is insufficient. Analgesics should be trialled alone or in combination for a period of three months. If they prove to be ineffective, a referral should be considered[6]

.

When response to individual therapy is insufficient, analgesia in combination with hormonal treatment is another option.

Hormone treatment

If conception is not desired, hormonal treatment (e.g. combined oral contraceptives [COCs] or progestogens) should be trialled in suspected, confirmed or recurrent endometriosis. If hormonal treatment is ineffective, not tolerated or contraindicated, a referral should be made to gynaecology services (paediatric, adolescent or adult depending on age) or specialist endometriosis services[6]

.

Combined oral contraceptives

Although COCs are not licensed for the treatment of endometriosis, they are widely used to treat the associated pain, offer contraceptive protection and control the menstrual cycle, without permanent negative effects on subsequent fertility[6]

.

Monophasic COCs (e.g. 30–35 micrograms of ethinylestradiol and norethisterone, norgestimate or levonorgestrel) are usually prescribed first line[4]

. The NICE clinical knowledge summary recommends that a conventional regimen of three months should be trialled, although tricycling or continuous use is recommended when control of symptoms is inadequate, or if there is a symptomatic flare while off active treatment[4]

. The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health reports that evidence suggests that a continuous rather than a cyclical COC regimen is advantageous in the management of endometriosis[18]

.

COCs are usually prescribed first line; however, oral progestogens (see below) should be offered when hormonal contraception has been declined.

Progestogens

Progestogen-only contraceptives (e.g. intrauterine levonorgestrel, oral desogestrel 75 micrograms, depot medroxyprogesterone and subdermal etonogestrel) may also be considered[4]

. Meanwhile, oral non-contraceptive options include medroxyprogesterone and norethisterone[4]

.

By inhibiting ovulation, progestogens reduce oestrogen levels and induce endometrial atrophy[4]

.

Other hormone treatments

Secondary care treatment options include gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (e.g. goserelin) and androgens (e.g. danazol). GnRH agonists inhibit pituitary secretion via negative feedback, while androgens directly inhibit pituitary gonadotrophins, both causing amenorrhoea and inducing a reversible menopausal state that results in the regression of endometriosis[4]

.

Furthermore, the addition of HRT to GnRH agonists can be considered to reduce side effects (e.g. loss of bone density) of GnRH agonists — this is known as ‘add-back therapy’. However, the re-introduction of oestrogen may result in a reactivation of endometriosis symptoms, so women need to be monitored carefully[4]

(see Table 2).

Tricyclic neuromodulators

Neuromodulators (such as tricyclics, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, local anaesthetics, capsaicin patches, N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists, anticonvulsants, and nerve blocks) have been used for symptom control in both primary and secondary care[19]

.

NICE recommends a choice of amitriptyline, duloxetine, gabapentin or pregabalin be trialled in the first instance, and if it is not effective or tolerated, any of the other three options should be considered[6]

.

For further guidance, please refer to the NICE clinical guideline on neuropathic pain in adults

.

| Medicine | Dose | Common adverse effects | Cautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selected initial management options | |||

| Paracetamol | 500–1,000mg orally every 4 to 6 hours, maximum 4,000mg/24 hours | None listed | Caution in use in patients with: weight under 50kg; chronic alcohol consumption; chronic dehydration; chronic malnutrition; hepatocellular insufficiency; or long-term use (especially in those who are malnourished)

|

| Ibuprofen | 300–400mg orally three times per day (increase by 400mg daily if required), with maintenance therapy 200–400mg three times per day | None listed as common, however, the frequency of asthma is not known | Caution in use in patients with: allergic disorders; cardiac impairment; cerebrovascular disease; coagulation defects; connective tissue disorders; Crohn’s disease; heart failure; ischaemic heart disease; peripheral arterial disease; risk factors for cardiovascular events; ulcerative colitis;or uncontrolled hypertension. Caution in use in older people |

| Combined oral contraceptives

| Commence a three-month trial of a conventional regimen — switch to tricycling or continuous use if symptom control is inadequate | Acne; fluid retention; headaches; metrorrhagia (spotting); nausea; weight gain | Caution in use in patients with: active trophoblastic disease; Crohn’s disease, gene mutations associated with breast cancer; history of severe depression; hyperprolactinaemia; inflammatory bowel disease; migraine; history of hypertriglyceridaemia; risk factors for arterial disease; risk factors for venous thromboembolism; sickle cell disease; or undiagnosed breast mass |

| Levonorgestrel (intrauterine progestogen-only) | 20 micrograms per 24 hours — intrauterine device is inserted during the last days of menstruation or withdrawal bleeding, or at any time if amenorrhoeic (effective for four years) | Back pain; breast abnormalities; depression; device expulsion; hirsutism; increased risk of infection; decreased libido; nervousness; ovarian cyst; pelvic disorders; uterine haemorrhage (on insertion); vaginal haemorrhage (on insertion); vulvovaginal disorders; weight gain | Caution in use in patients with: disease-induced immunosuppression; acute venous thromboembolism; anaemia; anticoagulant therapy; diabetes; drug-induced immunosuppression; endometriosis; epilepsy; fertility problems; history of pelvic inflammatory disease; jaundice; marked increase of blood pressure; migraine; nulliparity; severe arterial disease; severe cervical stenosis; severe headache; severe primary dysmenorrhoea; severely scarred uterus; or young age. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy and increased risk of expulsion if inserted before uterine involution

|

| Medroxyprogesterone (non-contraceptive progestogen) | 10mg orally three times per day for 90 consecutive days, begin treatment on day one of cycle

| Increased appetite; cervical abnormalities; constipation; fatigue; headache; hyperhidrosis; hypersensitivity; nervousness; oedema; tremor; vomiting | Caution in use in patients with: asthma; cardiac dysfunction; conditions that may worsen with fluid retention; diabetes; epilepsy; history of depression; hypertension, migraine; or susceptibility to thromboembolism. Possible risk of breast cancer |

| Amitriptyline (tricyclic neuromodulator) | Commence at 5–10mg orally at night (increase by 10mg every two weeks). Maximum 30mg/day | Anticholinergic syndrome; drowsiness; increased QT interval | Caution in use in patients with: cardiovascular disease; chronic constipation; diabetes; epilepsy; history of bipolar disorder; history of psychosis; hyperthyroidism; increased intra-ocular pressure; patients with a significant risk of suicide; phaeochromocytoma; prostatic hypertrophy; susceptibility to angle-closure glaucoma; or urinary retention

|

| Selected specialist management options | |||

| Goserelin (gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist) | 3.6mg, administered to the anterior abdominal wall, monthly for maximum of six months (peri-operative dose differs) | Alopecia; arthralgia; bone pain; breast abnormalities; depression; impaired glucose tolerance; gynaecomastia; headache; heart failure; hot flushes; hyperhidrosis; altered mood; myocardial infarction; neoplasm complications; paraesthesia; sexual dysfunction; skin reactions; spinal cord compression; vulvovaginal disorders; weight changes | Caution in use in patients with: depression; diabetes; hypertension; patients with metabolic bone disease; or polycystic ovary syndrome |

Sources: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[4],[7] | |||

Referrals

Recurrent, persistent or severe signs of endometriosis require referral to a gynaecologist. NICE currently recommends that if pelvic signs of endometriosis are present, or if initial management is contraindicated, ineffective or not tolerated, women should be referred[6]

. Furthermore, specialist endometriosis services should also be enlisted if women have suspected or confirmed deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder or ureter or in women aged 17 years and under[6]

.

Hormonal treatment should not be offered to women with endometriosis who are trying to conceive because it does not improve spontaneous pregnancies — surgical management is preferred when fertility is a priority[6]

.

Non-pharmacological management

Lifestyle advice can be provided to patients with endometriosis to aid symptom relief (see Box 2).

Surgical treatment is an option for patients who do not respond to pharmacological treatment or lifestyle interventions. Laparoscopic treatment with prior patient consent should be considered during diagnostic laparoscopy for peritoneal endometriosis (not involving the bowel, bladder or uterus) or uncomplicated ovarian endometriomas[6]

. However, laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation for chronic pelvic pain is not recommended by NICE.

Further surgery may be required for recurrent endometriosis, deep endometriosis (bowel, bladder or ureter involvement) or when complications arise[6]

. For patients with deep endometriosis, three months of taking a GnRH agonist should be considered prior to surgery as an adjunct. Excision should be considered rather than ablation of endometriomas, and fertility should be conserved if desired[6]

. Hormonal treatment (e.g. COCs) should be considered after excision or ablation to prolong surgical benefits and to manage symptoms[6]

.

If a hysterectomy is indicated, for example if a woman has adenomyosis or menorrhagia that has not responded to other treatments, this should be combined with laparoscopic excision of all visible endometriotic lesions at the time of the hysterectomy. Laparoscopic hysterectomies should be performed when combined with surgical treatment of endometriosis, with or without oophorectomy (removal of one or both ovaries), unless there are contraindications. Patients may still require further surgery after a hysterectomy owing to endometriosis recurrence.

Box 2: Lifestyle advice

- Heat: warm baths and heat packs can provide pain relief;

- Physiotherapy: exercise programmes that strengthen pelvic floor muscles help reduce pain, as well as manage stress and anxiety;

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator (TENS) machines: TENS machines are thought to provide relief by either blocking nociceptor neurotransmitters or by producing endorphins to counter nociception.

Sources: Endometriosis UK[17]

Complications and prognosis

Studies have found that diagnosis of endometriosis can be delayed for up to ten years owing to diagnostic and clinical challenges, resulting in both disease progression and a decrease in quality of life[7]

.

Around 30–50% of women with endometriosis have sub-fertility[4]

. Fertility problems can occur as a result of damage to the ovaries or fallopian tubes, or changes to the pelvic anatomy as a result of adhesions causing inappropriate fusion (e.g. of organs) or endometriomas[11]

.

Endometriomas can develop depending on the proximity of the endometriosis tissue to the ovaries. These fluid-filled cysts can become enlarged and painful[11]

. Although pharmacotherapy will not improve fertility, surgery to remove visible patches of endometriosis tissue can be beneficial[11]

.

Infertility is uncommon in women with mild-to-moderate endometriosis, with eventual resultant pregnancies without the requirement for treatment. Although IVF may be an option in those who find it difficult to conceive, success tends to be limited in those affected by endometriosis[11]

.

The prognosis of endometriosis is variable; in 20–50% of women, symptoms will recur after medical or surgical intervention. Deposits can also spontaneously regress in up to 30% of women after 6–12 months[4]

.

Role of the pharmacist

NICE recommends that analgesics, such as NSAIDS and paracetamol, are trialled alone or in combination for three months in patients with endometriosis[6]

. Pharmacists should check the following:

- There is an appropriate supply of the medicine;

- The correct dose is prescribed depending on any existing disease state;

- There are no drug–drug or drug–disease state interactions;

- There are no contraindications.

The same applies for hormonal treatments and neuromodulators. Advice should also be given on administration and adverse effects (see Table 2).

For an example case study, see Box 3.

Box 3: Example case study

Samantha, an 18-year-old Caucasian woman, enters the pharmacy and asks to speak to the pharmacist. She explains that, over the past 12 months, her period pain appears to be getting worse, with very heavy flow. On some days, it is so bad that she has had to miss work.

After questioning the patient, she explains that she reached puberty quite early and had her first period aged ten years. She also informs you that her mother has endometriosis and needed surgery for it in the past. On further discussion, the patient explains that she is exhausted most of the time but does not have any other symptoms (e.g. chronic pelvic pain, cyclical gastrointestinal symptoms). She is currently not on any medicine and has no known allergies.

Initial advice and treatment recommendations

Samantha is advised to keep a diary of her symptoms and to take ibuprofen tablets (400mg three times per day with/after food) prior to the onset and during her period. Heat packs or warm baths are also recommended to help with the symptoms, and that Endometriosis UK may be a helpful resource. The patient is told to visit her GP if symptoms persist, particularly since her mother has endometriosis.

After one month

The patient returns to the pharmacy and explains that the ibuprofen has helped, but her pain is still problematic. It is recommended that she takes ibuprofen in conjunction with paracetamol tablets (1g four times per day). The pharmacist reiterates that she should see her doctor for further advice/treatment.

Follow-up after GP referral

A few months later, Samantha presents to the pharmacy with a prescription for a combined oral contraceptive (COC). She explains that although the ibuprofen, paracetamol and heat packs have helped to some degree, she is still having to miss work. Therefore, her GP has prescribed a COC while she waits three months for an appointment with a specialist. In the meantime, she was advised to continue with analgesics for symptom relief.

She is advised to take the pill daily for 21 days, followed by a 7-day break, and that while the pill is usually well tolerated, she needs to be aware of some of the side effects such, as:

- Acne;

- Fluid retention;

- Headaches;

- Spotting;

- Nausea;

- Weight gain.

Furthermore, she is advised that if she experiences any sudden severe chest pain, sudden breathlessness, unexplained swelling or severe pain in the calf of one leg, severe stomach pain, yellowing of whites of the eyes or skin, or other serious neurological effects, that she should cease treatment and return to her GP.

Three months later, Samantha returns to the pharmacy with another prescription for the COC. She explains that she has had a few tests and had minor surgery during a diagnostic procedure where endometriosis was confirmed. She explains that her symptoms are much more manageable and that she is grateful for the help and advice that the pharmacist gave her.

How to have effective consultations on contraception in pharmacy

What benefits do long-acting reversible contraceptives offer compared with other available methods?

Community pharmacists can use this summary of the available devices to address misconceptions & provide effective counselling.

Content supported by Bayer

References

[1] Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. New NICE guideline on Endometriosis published. 2017. Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/about-us/nga/nga-news/nice-guideline-endometriosis (accessed August 2019)

[2] Endometriosis UK. Understanding Endometriosis. 2014. Available at: https://www.endometriosis-uk.org/understanding-endometriosis (accessed August 2019)

[3] Prentice A. Endometriosis. BMJ 2001;323(7304):93–95. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.93

[4] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Endometriosis. 2014. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/endometriosis (accessed August 2019)

[5] Endometriosis UK. Causes of endometriosis. Available at: https://www.endometriosis-uk.org/causes-endometriosis (accessed August 2019)

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Endometriosis: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG73]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng73 (accessed August 2019)

[7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings. Clinical guideline [CG173]. 2013. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG173/chapter/1-Recommendations#key-principles-of-care (accessed August 2019)

[8] Medscape. Endometriosis. 2018. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/271899-overview#a3 (accessed August 2019)

[9] Kuznetsov L, Dworzynski K, Davies M et al. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2017;358:j3935. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3935

[10] Mayo Clinic. Endometriosis. 2019. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/endometriosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20354656 (accessed August 2019)

[11] NHS. Endometriosis. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/endometriosis/complications (accessed August 2019)

[12] Bernardi LA & Pavone ME. Endometriosis: an update on management. Women’s Health 2013;9(3):233–250. doi: 10.2217/whe.13.24

[13] Hansen KA & Eyster KM. Genetics and genomics of endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2010;53(2):403–412. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181db7ca1

[14] Fung JN & Montgomery GW. Genetics of endometriosis: State of the art on genetic risk factors for endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;50:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.012

[15] Johns Hopkins Medicine. Endometriosis. 2019. Available at: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/gynecological_health/endometriosis_85,p00573#risk (accessed August 2019)

[16] Better Health Channel. Endometriosis. 2018. Available at: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/endometriosis (accessed August 2019)

[17] Endometriosis UK. Pain relief for endometriosis. 2007. Available at: https://www.endometriosis-uk.org/pain-relief-endometriosis#Pain-modifiers (accessed August 2019)

[18] The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Combined Hormonal Contraception. 2019. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/combined-hormonal-contraception/ (accessed August 2019)

[19] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Endometriosis: diagnosis and management. Appendices D, F and H–J. 2019. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG173/chapter/1-Recommendations#key-principles-of-care (accessed August 2019)

[20] British National Formulary. Paracetamol. 2016. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_970446495?hspl=paracetamol (accessed August 2019)

[21] British National Formulary. Ibuprofen. 2016. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_778077044?hspl=ibuprofen (accessed August 2019)

[22] British National Formulary. Ethinylestradiol with levonorgestrel. 2017. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_296203164 (accessed August 2019)

[23] British National Formulary. Levonorgestrel. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_944861997?hspl=levonorgestrel (accessed August 2019)

[24] British National Formulary. Medroxyprogesterone acetate. 2017. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_500817750?hspl=depot&hspl=Medroxyprogesterone%20acetate (accessed August 2019)

[25] British National Formulary. Amitriptyline hydrochloride. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_366685569 (accessed August 2019)

[26] British National Formulary. Goserelin. 2017. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_219676800?hspl=goserelin (accessed August 2019)