Tim Graham / Robert Harding / Rex Features

Summary

In this article you will learn:

- The increased risks of health conditions associated with alcohol misuse

- How to assess patients’ alcohol intake and when to refer the patient for further advice

- How to conduct a brief intervention to encourage a patient to reduce their alcohol intake

Alcohol misuse is an international concern. Globally, 6.13 litres of pure alcohol is consumed per person aged 15 years or older each year and it is responsible for around 4% of all deaths worldwide[1]

.

In Great Britain, 58% of adults drink alcohol at least once a week[2]

, and in England around one in three men and one in four women drink more than the daily recommended limits at least once a week[2]

.

In 2012, there were 8,367 deaths directly related to alcohol in the UK, of which 65% were in men[3]

, and in 2012–2013, there were more than one million hospital admissions related to alcohol consumption in England[4]

. Alcohol harm is estimated to cost society in England £21bn each year[4]

.

The effects of alcohol

Pure alcohol, or ethanol, is a volatile, colourless liquid that is a contributing factor in more than 60 medical conditions (see ‘Health risks of alcohol misuse’). It affects the body through a combination of mechanisms. Alcohol alters neurotransmitter activity, primarily by binding to the GABAA receptor, which leads to its pronounced sedative effect as blood-alcohol concentration increases. It is a neurotoxic agent and can cause acute problems, such as intoxication and memory loss, and long-term chronic neurological problems, such as Wernicke-Korsokoff syndrome.

Alcohol also causes cellular toxicity, particularly in the liver. Heart muscle can also be damaged, leading to cardiomyopathy, as can the gastrointestinal tract, causing conditions ranging from gastritis to cancer.

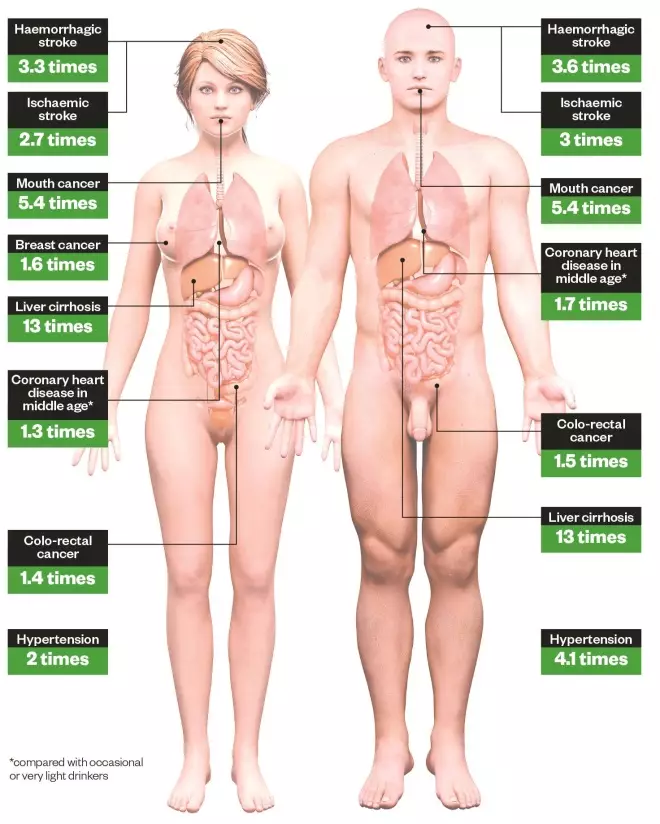

Health risks of alcohol misuse

Increased risks of developing health conditions associated with drinking more than 7.5 units/day (men) or 5 units/day (women) compared with non-drinkers. Source: Department of Health

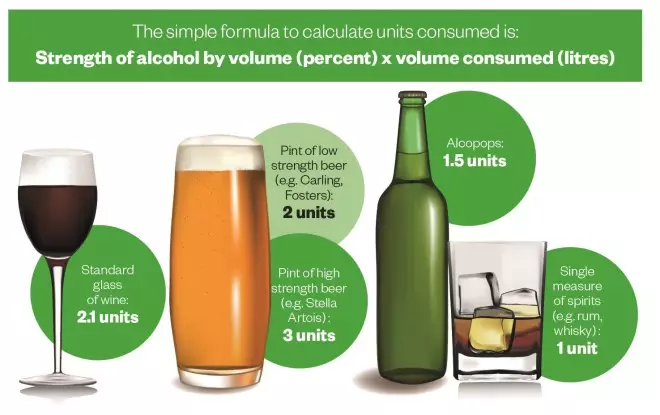

The volume of alcohol consumed is measured in units. In the UK, a unit of alcohol is defined as 8g of ethanol (see ‘Calculating alcohol consumption’).

The Department of Health recommends that[6]

:

- Men should drink no more than three to four units of alcohol a day and have at least two alcohol-free days a week;

- Women should drink no more than two to three units of alcohol a day and have at least two alcohol-free days a week;

- Pregnant women (and women trying to conceive) should not drink alcohol at all. If they choose to drink they should drink no more than one to two units once or twice a week and not get drunk;

- ‘Binge drinking’ is defined as twice the upper limit of the maximum daily drinking level (i.e. six units for women and eight units for men).

Calculating alcohol consumption

Assessing alcohol misuse

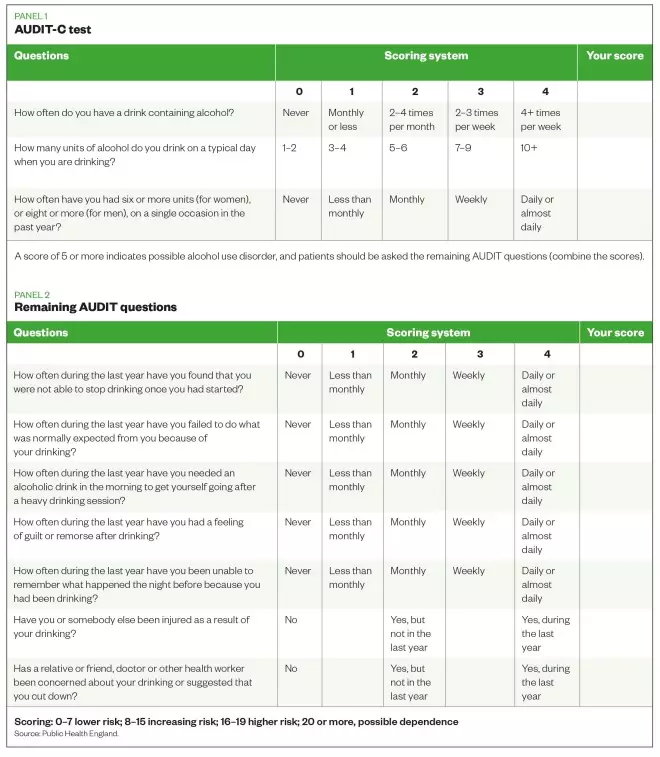

The gold-standard screening tool to identify alcohol misuse is the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Tool (AUDIT). The full version uses ten questions to assess frequency of drinking, dependency indicators and problems related to alcohol use[7]

. A score of 8–15 indicates increasing risk of alcohol misuse; 16–19 points to a higher risk and 20 or more indicates possible alcohol dependency[7]

.

A shortened version of the test, known as AUDIT-C, uses three questions from the AUDIT screen. It is more convenient to employ and can be self-administered by the patient. Although not as sensitive as the full AUDIT tool, it is quick to administer in and scratch cards can be used to engage individuals.

A score of 5 or more is regarded as an AUDIT-C positive score and indicates a possible alcohol use disorder (see ‘AUDIT-C test’).

Brief interventions

Patients identified as potentially at increased risk of an alcohol use disorder (AUDIT score 8-19) should receive a brief intervention by the pharmacist or an appropriately trained staff member. Brief interventions help one in eight people at risk of an alcohol use disorder reduce their drinking to a low level of risk[8]

.

A brief intervention usually lasts around three to five minutes, and can be supported with appropriate literature that highlights the risks associated with drinking at increased levels (see ‘Further resources’).

Advice should be provided in a structured manner, such as the FRAMES framework:

- Feedback: discuss the patient’s personal risk or impairment;

- Responsibility: emphasise the patient’s personal responsibility for change;

- Advice: suggest how the patient can cut down or abstain if indicated;

- Menu: offer the patient alternative options for changing their drinking pattern and, jointly with the patient, set a target for reduction;

- Empathetic: listen reflectively without confronting the patient; explore with the patient the reasons for change as they see their situation;

- Self-efficacy: enhance the patient’s belief in their ability to change.

Referral advice

Brief interventions are not suitable for patients presenting with possible alcohol dependency (AUDIT score of 20 or more), which is a complex medical and psychosocial condition that requires specialist support. Patients with suspected alcohol dependency should be referred to their GP or local specialist alcohol service.

Dependent drinkers should not be advised to stop drinking immediately, as this may lead to delirium tremens, a potentially life-threatening withdrawal complication. This develops in around 5% of cases of withdrawal and has a mortality rate of 5%[9]

. It presents as confusion, disorientation, agitation, tachycardia, hypertension, fever and hallucinations. Delirium tremens is a medical emergency and pharmacists should call an ambulance if a patient presents with these symptoms.

Raising awareness

Raising the issue of drinking behaviour with patients can be difficult. However, many community pharmacies have delivered this service successfully in a number of regions across the UK[10]

[11]

.

Pharmacy teams should create an environment in the pharmacy that supports a discussion with patients about alcohol. This can include using posters in the pharmacy, or creating window displays that engage patients. This will also support increased public awareness of the risks associated with alcohol.

All pharmacy staff should be trained and involved in providing alcohol intervention services. Training could be made available through area teams, the local public health department or specialist alcohol service, or through e-learning from Public Health England (see ‘Further resources’).

When running an alcohol awareness campaign, staff should try to initiate a discussion with all people who enter the pharmacy or hand in a prescription. This ensures that patients do not feel targeted, and conversations about alcohol become a regular part of pharmacy practice. Patients should also be asked about alcohol intake as part of routine healthy living advice, for example during a medicines use review (MUR).

Scratch cards, such as those available from the National Pharmacy Association (NPA), can also be placed in the pharmacy for patients to use and self-assess their alcohol intake. This provides a good non-confrontational approach to engaging patients at increased risk of alcohol use disorders.

Pharmacy staff must not be afraid of patients refusing the offer of an intervention. This is not a personal attack, and many patients may not be ready to discuss their alcohol use.

Starting a conversation

Pharmacy staff should develop and practice phrases to introduce the subject of alcohol misuse with patients. Each staff member should find a phrase they are comfortable with that elicits the best responses from patients.

Example phrases include:

- “I notice you have a prescription for X, Mr Smith. Alcohol can have a significant effect on your condition so we are asking all our patients taking X to complete an alcohol scratch card to see if it could be affecting them. Do you mind completing a scratch card while you wait for your prescription?”

- “As part of our current local public health campaign we are asking all our patients to complete an alcohol scratch card. Have you got a minute to complete one, Mrs X?”

Graham Parsons BPharm(Hons), PGDip (Comm Pharm), IPresc MRPharmS is a pharmacist with a special interest in substance misuse at Devon Clinical Commissioning Group and Steve Mills RMN RGN DipN is a Clinical Nurse Specialist (Alcohol), Torbay Alcohol Team

Further resources

Alcohol withdrawal

Brief intervention tools

Drink diaries

- NHS Choices Drinks Diary

- Devon Partnership NHS Trust drink diary

- Change4life drinks tracker (available on Apple and Android)

Useful websites

References

[1]World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva:WHO 2011.

[2]Office for National Statistics (2013). Statistical Bulleting: Drinking Habits Amongst Adults, 2012. London: Stationery Office 2013.

[3]Office for National Statistics. Alcohol-related deaths in the United Kingdom, registered in 2012. London: Stationery Office 2014.

[4]Health and Social Care Information Centre. Statistics on Alcohol – England 2014. HSCIC 2014. Available from: hscic.gov.uk

[5]Department of Health. Safe, Sensible, Social – Consultation on further action. London:DH 2008.

[6]NHS Choices. Alcohol units. [Online] Available from: nhs.uk/livewell (accessed 2 September 2014).

[7]World Health Organization. Audit: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. Second Edition. Geneva:WHO 2002

[8]Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE et al.Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction 2002;97:279-92

[9]Taylor D, Paton C & Kapur S. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines 10th Edition. London:Informa Healthcare 2009

[10]Parsons, G. Evaluation of the Alcohol Identification and Brief Advice (IBA) service in Plymouth Healthy Living Pharmacies (November to December 2011 [Online]. Available from: www.devonlpc.org (accessed 15 August 2014).

[11]Gray NJ, Wilson SE, Cook PA et al. Understanding and optimising an identification/brief advice (IBA) service about alcohol in the community pharmacy setting. Final Report. Liverpool PCT: 2012.