Power and Syred / Science Photo Library

In this article you will learn:

- The possible presenting symptoms of iron deficiency anaemia

- Patient groups who are at increased risk of iron deficiency anaemia

- How to start and manage iron replacement therapy

Mary, a 36-year-old woman, asks for your advice in the pharmacy. She is very active, eats a balanced vegetarian diet, and is a committed club-level hockey player. She has noticed that she has much less energy and has found her training sessions more challenging in the last couple of months. She is also now finding she has less energy at work and is uncharacteristically irritable.

She recalls that her mum had recurring problems with low iron levels and she thinks she may have an iron deficiency too. She mentions that she has experienced heavy menstrual bleeding, which she has heard is linked to low iron levels.

Assessment

Mary has described fatigue (tiredness, low energy, irritability). The differential diagnosis includes conditions such as depression, pregnancy, insomnia, hypothyroidism, and side effects of medicines.

Mary should also be asked whether she has had symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding, rapid weight loss, or significant change in bowel habit. These could suggest a serious underlying condition (e.g. bowel cancer).

Iron deficiency anaemia

Anaemia is lack of haemoglobin, which is proportional to the oxygen-carrying ability of red blood cells. It is defined by the World Health Organization as:

- Haemoglobin below 13g/dl in men aged over 15 years;

- Haemoglobin below 12g/dl in non-pregnant women aged over 15 years;

- Haemoglobin below 11g/dl in pregnant women.

As haemoglobin is required to effectively deliver oxygen to all the cells in the body, a shortage of haemoglobin inevitably leads to fatigue and other symptoms, including irritability and lethargy. If left untreated, this can progress to more severe symptoms, including shortness of breath, tachycardia and heart failure[3]

.

Iron is required to produce haemoglobin. Iron deficiency anaemia occurs when the iron deficit reaches a level where there is insufficient haemoglobin to make healthy red blood cells; this means red blood cell production is reduced, and smaller (microcytic) and paler (hypochromic) red blood cells are formed. Around 1mg of iron is used and excreted by the body each day[3],[4]

, and people who live in the Western world typically consume 15mg of iron each day[5]

, of which around 1mg is absorbed; this means that it only takes a comparatively small imbalance on an ongoing basis to cause iron deficiency.

Assuming Mary does not have symptoms suggestive of a more serious cause, the most likely diagnosis is iron deficiency anaemia.

Iron deficiency anaemia is usually related to intake of iron, and is particularly common in pre-menopausal women (occurring in around 5–12% of women), as menstruating women lose an additional 0.5–0.7mg of iron a day (averaged over a month); this means women with heavy menstrual bleeds are at increased risk of iron deficiency anaemia[1]

. Around 20–30% of all cases of iron deficiency anaemia are related to menstruation.

Women who are pregnant also require extra iron (an extra 1–2mg iron is needed a day, with increasing demand as pregnancy progresses), again increasing the risk of developing iron deficiency anaemia.

There is no evidence that iron deficiency anaemia is genetic (although family history can be a risk factor for some possible causes, e.g. colorectal cancer).

Meat and fish are among the richest sources of iron, and a vegetarian diet can make iron deficiency anaemia more likely to occur. It has been proposed that athletes are also more likely to become iron deficient because of training induced inflammation that lowers iron absorption[2]

.

Iron deficiency anaemia may also be secondary to more serious causes, including infection and side effects of medicines (see ‘Other causes of iron deficiency anaemia’).

Other causes of iron deficiency anaemia

Hookworm or tapeworm infection – patients should be asked if they have travelled abroad recently or have other rectal symptoms[3]

.

Medicines – non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin use are causative factors in 10–15% of cases as a result of gastric bleeding[4]

.

Coeliac disease – the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) recommends all iron deficiency anaemia patients should be screened for coeliac disease. It is implicated in 4–6% of cases.

Helicobacter pylori

– H.pylori is responsible for less than 5% of cases, and impairs iron absorption. It is often a missed cause of iron deficiency anaemia[5]

. It will not respond to iron, and symptoms may be masked by the side effects of iron treatment.

Other possible causes include a history of alcohol misuse, chronic kidney disease, malignancy and Crohn’s disease.

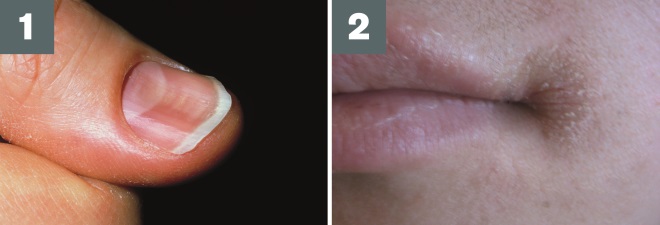

Pallor is a common sign of anaemia, which can be seen in even mild cases[2]

. Signs that are seen rarely but are indicative of more severe iron deficiency anaemia include:

- Shortness of breath (this requires urgent referral)

- Atrophic glossitis (inflamed, swollen tongue);

- Changes in the nails — they become brittle and ridged (koilonychia);

- Angular cheilitis (inflammation in the corners of the mouth)[2], [3]

.

Photo guide

Source: John Radcliffe Hospital / Science Photo Library and James Heilman, MD / Wikimedia

1) Koilonychia: also known as spoon nails, this presents as brittle, flat or concave nails

2) Angular cheilitis: can indicate iron deficiency anaemia, but may also be caused by a range of other conditions (e.g. dry mouth, lip licking, immunosuppression)

Referral

Patients with suspected iron deficiency anaemia, such as Mary, should be referred to their GP, who will order blood tests (full blood count, iron profile, C-reactive protein and liver function test) and rule out more serious conditions. The British Society of Gastroenterology states that the following results are indicative of iron deficiency anaemia[5]

:

- Reduced mean cell haemoglobin

- Reduced mean cell volume

- Low ferritin

- Raised total iron binding capacity

- Low reticulocyte haemoglobin.

Low ferritin is the most consistently reliable indicator of iron deficiency anaemia except if there is co-existent inflammatory disease (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, liver disease or infection), which can cause ferritin levels to rise and mask iron deficiency anaemia.

The threshold for iron deficiency anaemia is a ferritin below 12–15mcg/l without co-existing inflammatory disease; in patients with inflammatory disease a concentration of 50mcg/l or more could still be consistent with iron deficiency anaemia.

Iron deficiency anaemia and anaemia caused by chronic disease may co-exist.

Management

The first-line treatment for iron deficiency anaemia is iron replacement therapy. The course of iron tablets must be long enough to allow the haemoglobin to be normalised and to allow a full body iron store to be replete. Patients must be monitored thereafter to spot any relapses into iron deficiency anaemia early on[4]

.

The usual dose of elemental iron is 100mg to 200mg daily. The specific formulation or salt is not critical, but usually patients are prescribed one ferrous sulphate 200mg (contains 65mg elemental iron) tablet twice or three times a day. An alternative regimen is to take one tablet once a day, as studies have shown that 15–20mg elemental iron daily is as effective and has fewer side effects[2]

.

Slow-release iron tablets are not recommended as they do not increase the absorption of iron[5]

.

Mary should be advised to avoid taking iron tablets at the same time as a cup of coffee or tea, as this has been shown to reduce iron absorption dramatically[6],[7]

. There is mixed evidence on whether ascorbic acid aids absorption of iron[4]

. Medicines that reduce the acidity of the stomach (e.g. antacids, proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists) lower the absorption of iron and may reduce the effectiveness of iron treatment[2]

.

The most common side effect of iron treatment is constipation, which may improve during the course of treatment. Patients should be advised on the usual measures to reduce constipation, which include drinking plenty of water, eating a healthy, varied diet with plenty of fibre, and taking regular exercise. If constipation persists, a laxative can be prescribed.

Mary should be advised to stop taking iron if she develops a severe infection and seek advice from her doctor[6]

.

She should also be advised that it may take a few weeks (typically two to four weeks) of iron treatment before she notices a difference in energy levels. Patients on iron therapy should be monitored regularly, usually with a repeat blood test four to six weeks after starting treatment. Once levels are corrected, patients should continue taking iron tablets for a further three months to reduce the risk of relapse. Patients with a history of iron deficiency anaemia should also have a blood check annually to monitor ferritin levels, and should be advised to return to their GP if symptoms return in the interim[4]

.

All patients with iron deficiency anaemia should be advised to try to include iron rich foods in their diet. Dietary sources of iron are typically classified as haem (i.e. meat and fish) or non-haem (i.e. plants and legumes); it is particularly helpful to increase the haem content of the diet, as the body is more efficient at absorbing iron in this form[2]

.

This case study is focused on the basic management of iron deficiency anaemia. For further information, read ‘How to identify and treat adults with iron deficiency anaemia’, available here.

Niamh McGarry is a clinical pharmacist at Mater Hospital, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, and teacher-practitioner at Ulster Hospital, South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust.

References

[1] Mason, P. Understanding iron requirements. Pharm J 2008;281:47–51.

[2] De Loughery TG. Microcytic anemia. New Engl J Med 2014;371:134–1331.

[3] Longmore JM, Makin R & Longmore M. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. Fifth Edition. Oxford: OUP 2002.

[4] Goddard AF, James MW, McIntyre AS et al. (British Society of Gastroenterology) Guidelines for the management of iron deficient anaemia. Gut 2011;60:1309–1316.

[5] Frewin R, Henson A, Proven D et al. Iron deficiency anaemia. Clinical Review. BMJ 1997;314:360–364.

[6] Munoz M, GarcÃa-Erce JA, Remacha AF et al. Disorders of iron metabolism. Part 1: Molecular basis of iron homeostasis. J Clin Pathol 2011;64:281–286.

[7] Lynskey D & Machin S. How to identify and treat adults with iron deficiency anaemia. Clin Pharm. 2012;4:55–57.

You might also be interested in…

Pharmacy regulator considers giving up legal authority to conduct covert investigations of pharmacists

More than 40% of people with ADHD waiting at least two years to access mental health service, study finds