Shutterstock.com

For the vast majority of people, the benefits of physical activity far outweigh the risks. However, even moderate physical activity is not without risk of injury. Between April 2011 and February 2012, around 388,500 cases of sport-related injury were treated in emergency departments (A&E) in England, an increase of 14% compared with the previous year[1]

. Around half of A&E attendances for sports-related injuries involve males aged 10–29 years[1]

and an English survey found that football was responsible for more than a quarter (29%) of sport incidents[2]

, although rugby accounts for the highest injury rate (injuries/participation occasions)[3]

.

The location and accessibility of community pharmacies means that pharmacists are likely to consult with patients about and observe a wide range of sport and physical activity related injuries. Pharmacists and healthcare professionals should, therefore, have an understanding of the risk factors and prevention of sports-related injuries, be able to identify common injuries, as well as provide specific advice to patients on their effective management, including the role over-the-counter (OTC) pharmacological treatments.

Common minor sport-related conditions, including

verrucas

[4]

, athlete’s foot

[5]

and foot pain

[6]

, have been covered in previous articles and do not feature in this article.

Injury and the healing process

Risk factors and prevention

Common risk factors for sports injury include inadequate warm up, fatigue, over intensive training, unsuitable equipment and a changed environment (e.g. very hot weather, poor lighting, or physical contact with another person or equipment)[7]

.

Injury prevention can be achieved through dynamic stretching before activity[8]

. Dynamic stretching consists of exercises that use sport-specific movements to prepare the body for exercise (see additional resources for a useful video). The athlete moves parts of their body, gradually increasing reach, speed of movement or both. This contrasts with static stretching where the athlete reaches forward to a point of tension and holds the stretch. Although static stretching has been used for years, it is now considered to decrease performance and will not protect against injury in the majority of cases[9]

. Other ways to prevent injury include the use of protective equipment (e.g. mouthguards, helmets or knee pads) and appropriate, activity-specific training regimens, which include recovery between activity episodes.

The healing process and inflammation

There are three overlapping phases in the healing process accompanying injury. The initial inflammatory response promotes the influx of inflammatory mediators (e.g. leucocytes and macrophages), which effectively clean the injury site of unwanted debris through phagocytosis (the process of engulfing particles such as bacteria, parasites, dead host cells, and cellular and foreign debris by a cell)[10]

. Inflammatory mediators also provide some protection against infection and the presence of inflammation is in itself part protective, as it significantly reduces movement. The vascular element of the early inflammatory process includes clot formation, scar tissue and proliferation of blood vessels. The amount of inflammation is related to the extent of vessel damage. Early appropriate treatment of an injury can enhance recovery by limiting the inflammatory process at an appropriate phase of recovery.

Symptoms of inflammation include:

- Redness;

- Pain;

- Heat;

- Swelling;

- Sometimes loss of function.

Assessment and management of injury in the pharmacy

Many pharmacists or healthcare professionals have not received the required training, time, facilities or equipment to undertake a full diagnostic assessment. However, they are able to determine whether the condition is mild, self-limiting and can be managed with appropriate self-care and advice, or whether the patient requires referral.

Effective early management can reduce pain, promote rapid healing and shorten rehabilitation. Taking a comprehensive history from the patient is vital, since understanding the cause of the injury can help identify the possible mechanism of injury and likely severity[11]

.

Points to consider when taking a history from the patient include:

- Was the patient treated immediately or later after the injury?

- What treatment was received?

- Was the patient able to continue with their activity?

- What was the intensity of the activity leading up to sustaining the injury?

- Has this or any other injury occurred before?

- Is this an acute or chronic injury?

- Other medical history including medication (see ‘How to take a detailed medicines history’

[11]

, for more information).

Examination of the patient

When examining a patient’s injury, preferably in a consultation room, it is recommended that healthcare professionals request that the patient removes their own footwear to avoid additional pain. However, an injured foot or lower leg may swell once the footwear is removed and, therefore, may not be replaceable.

During the examination, it is important to look for any of the following symptoms and the degree to which they are present as this may indicate underlying damage and the severity of the injury:

- Skin damage;

- Bruising;

- Swelling;

- Fluid accumulation;

- Lumps;

- Deformity;

- Inability to weight bear;

- Restriction of movement;

- Pain.

The presence of deformity, inability to use the limb or weight bear on a leg associated with severe pain could be indicative of a possible fracture or dislocation. In these instances, it may be useful to consult the Ottowa Guidelines[12]

,[13]

on when an X-ray is recommended, before referring the patient to secondary care (e.g. A&E).

Injuries to the head, cervical spine, or the thoracic or abdominal organs should be treated as potentially life-threatening and referred to secondary care urgently. A patient with suspected concussion following a blow to the head, face, neck or where an ‘impulsive’ force may be transmitted to the head, who presents subsequently with changes in behaviour, vomiting, dizziness, headache, doublevision or excessive drowsiness requires urgent medical assessment.

General management of injuries in the pharmacy

Two approaches exist for the immediate treatment of acute injuries, the main one being a simple five-step protocol, PRICE (P rotection, R est, I ce, C ompression, E levation). Rest after injury is usually considered appropriate for the first 48–72 hours. During this time, non-weight bearing is usually recommended and crutches or slings can provide support. After 48 hours, MICE (M ovement, I ce, C ompression, E levation) can be introduced, with gentle movement replacing rest. If pain is experienced on repetition of gentle movement, or if there is constant pain, then rest should continue for another 24 hours before the introduction of movement is tried again. If this is unsuccessful, referral to a GP should be considered. Earlier referral may be advised if pain is particularly severe.

Drug treatment

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used to treat many of the symptoms of injury and generally work to reduce pain, reduce heat around the affected area, decrease swelling and improve mobility. Pain relief should start soon after the first dose and a full analgesic effect occurs within a week. Although evidence suggests that long-term use of NSAIDs to manage fracture pain and inflammation carries the risk of impaired bone healing, the use of NSAIDs for shorter periods probably has little impact on the overall healing process[14]

.

In tendinopathies (painful tendons), where inflammation plays a lesser role, NSAIDs probably have little influence on healing but may be of some benefit on a short-term basis for analgesia.

With sprains, strains or tears of ligaments, NSAIDs may be used to limit pain and swelling, increasing the chances of the patient regaining function and returning to activity sooner, if used in the short-term (three to seven days)[14]

.

Evidence also supports the short-term use of NSAIDs for the management of muscular injury, to provide pain relief and allow earlier resumption of normal activity. If used long-term, the risk of side effects (e.g. gastrointestinal and cardiovascular effects) increases and the patient should be counselled accordingly. It is estimated that 20–30% of people taking NSAIDs regularly experience side effects[15]

.

Topical NSAIDs can be applied directly to the affected area or site of the injury. Topically applied NSAIDs penetrate the skin and result in therapeutically significant concentrations in underlying inflamed soft tissues, joints and synovial fluid, probably entering the synovial joint mainly via systemic circulation[16]

.

Clinical trials generally demonstrate that topical NSAIDs are slightly more effective than topical placebo preparations when used to relieve musculoskeletal pain in acute musculoskeletal conditions (e.g. strains, sprains and overuse injuries) and lack associated systemic side effects (e.g. gastrointestinal bleeding and renal impairment)[17]

. Local side effects may include skin reactions (e.g. dermatitis, pruritis or erythema) and photosensitivity reactions, which usually resolve on discontinuation of treatment. Patients are unlikely to gain any additional benefits by using topical NSAIDs as an adjunct to oral NSAID therapy. Topical NSAIDs as sole therapy may be useful if the patient cannot tolerate oral NSAIDs.

Paracetamol and opioids can be recommended for rapid treatment of pain and consequent muscle spasm. Opioid use is limited by the development of side effects, such as constipation, dizziness and drowsiness, which may arise even at OTC doses, especially with prolonged use.

Common injuries and their specific management

Muscle injury and soreness

Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is distinct from pain felt during exercise. It typically develops 12–24 hours after exercise has been performed and may produce the greatest pain 24–72 hours post-exercise. Soreness is not caused by lactic acid accumulation — it is a side effect of the repair process that develops in response to microscopic muscle damage[18]

. DOMS can be experienced after any activity and may even occur in elite athletes if the intensity of training is stepped up.

NSAIDs and massage may help relieve symptoms of DOMS[19]

. Patients should avoid heat and the use of heat rubs in the first 48 hours after injury, as heat encourages bleeding, which could be detrimental. Thermotherapy and cryotherapy has been covered in a previous article[20]

. The gradual build-up of exercise is the best preventive measure.

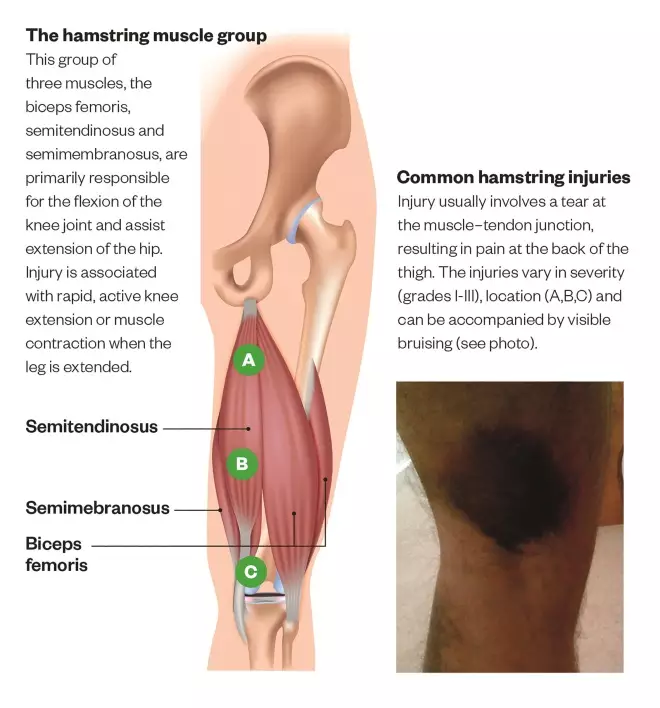

Hamstring injuries account for about a third of all lower-limb injuries in sport and are especially common in sprinting and jumping sports, martial arts and water skiing[21]

. The hamstrings are a group of three muscles that act as flexors of the knee and extensors of the hip (see ‘Figure 1: The hamstring muscles, common injuries and their locations’). Injury is associated with rapid, active knee extension or muscle contraction when the leg is extended. Injury usually involves a tear at the muscle–tendon junction, resulting in pain at the back of the thigh. It may be sudden and disabling, and is often accompanied by a popping sound (see Figure 1). Reoccurrence is common unless treated properly.

PRICE should be recommended as a first step, however, patients may also require pain relief. In this instance, the use of NSAIDs should be limited to a few days[21]

. Eccentric resistance exercise under specialist supervision is recommended to prevent re-injury[22]

.

Figure 1: The hamstring muscles, common injuries and their locations

Source: Shutterstock.com, Daniel Cardenas / Wikimedia Commons

Hamstring injuries account for around a third of all lower-limb injuries in sport and are common in sprinting and jumping sports, martial arts and water skiing. Reoccurrence is common unless treated properly.

Common hamstring injuries and locations:

A. Grade I: Strain

Patient may experience tightness at back of the thigh, discomfort, mild swelling and spasm. Bending of the knee unlikely to cause much pain.

B. Grade II: Tearing

Patient may present with a limp, hamstring muscle swelling and tenderness. Bending of the knee is likely to cause pain.

C. Grade III: Complete tear

Patient will experience severe pain and weakness in the muscle. Swelling immediately noticeable and bruising will usually appear within 24 hours.

Tendinopathies, or lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow), affects the tendon that attaches the muscles of the forearm to the prominent part (the lateral epicondyle) of the elbow. The condition usually results from overuse but may be related to poor technique or inappropriate/faulty equipment. Symptoms include pain and tenderness over the tendon close to the elbow, but may also spread up and down the arm. Hand grip may also be affected. It is common in racquet sports and golf, particularly in patients aged 40–60 years.

PRICE should be recommended in the acute stages of the injury with stretching and eccentric loading introduced after 48 hours, depending on pain response. Topical NSAIDs may be effective, although there is generally thought to be little inflammation with this condition[23]

. A reassessment of equipment and technique should be recommended to the patient to prevent long-term problems. Chronic cases should be referred to a GP or specialist for assessment.

Ligament injuries occur in the bands of fibrous connective tissue, which connect bone to bone, and can be classified into three grades:

- Grade I: where the ligament is stretched. There may be micro tears and some discomfort only;

- Grade II: involves a partial tear with moderate pain and swelling. There is some loss of mobility and the joint may be weak;

- Grade III: full rupture of the ligament with significant pain, marked swelling and bruising. There is loss of function and the patient cannot weight bear.

Ligament injuries of the ankle are the most common sporting injury, with an estimated one sprain per 10,000 people per day, with women more prone to this injury than men[24]

. Ankle sprain is particularly frequent in participants of ball sports involving jumping and landing (e.g. netball).

The stability of the ankle is ensured by three sets of ligaments. The most commonly injured of these is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), when the ankle is turned or twisted to the lateral side (an ankle inversion). Recurrence is common, with more than 50% of patients suffering a repeated problem and a quarter of all patients who twisted their ankles experiencing a similar injury regularly. Grade I ankle sprains (unless recurring) can be treated with PRICE (although evidence is lacking) and short-term use of NSAIDs[25]

.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a large ligament in the knee that helps provide stability by limiting the forward translation of the lower leg in relation to the thigh and prevents excessive lateral rotation of the knee. It is usually damaged in twisting of the limb, especially if in a flexed position. A torn ACL will result in bleeding into the joint, which causes severe pain and immediate swelling. The patient may have been aware of a ‘pop’ at the moment of injury. Damage to the meniscus and other knee ligaments may occur simultaneously[26]

. Patients with a suspected knee ligament damage should be referred to a physical therapy specialist for assessment.

The plantar fascia is the long ligament that joins the heel bone (calcaneus) to the ligaments at the base of the toes. In plantar fasciitis, the ligament becomes stretched as a result of chronic overuse. An acute injury should be treated with PRICE and analgesics/NSAIDs. Exercise that involves rolling the foot over a bottle of water filled with ice can be recommended for milder cases. Stretching, wearing training shoes, avoiding barefoot walking and losing weight (if appropriate) have all been shown to be beneficial[27],[28]

. Recurrent conditions require referral to a GP or specialist for assessment and treatment.

Skin problems

Chafed skin can be common in people who exercise or play sport and usually affects the thighs, underarms, nipples and under breasts. If the area becomes damp and dirty, it can become sore and may bleed, making it prone to fungal infection. Petroleum jelly, plasters or similar, or a change of clothing as appropriate can assist with prevention.

The skin should be cleaned thoroughly but gently using a non-perfumed soap to remove sweat and dirt as soon as possible after activity. Suspected fungal infection usually responds to topical antifungal therapy.

Referring sport and physical activity related injuries

In ‘Table 1: Referring patients with sport and physical activity related injuries to specialists’, there is further information on the referral pathway for specialists providing treatment for sport and physical activity related injuries, as well as details of the type of injuries they generally treat. In ‘Box 1: Pharmacists as athlete support personnel’, there is additional information on the role of pharmacists in supporting athletes.

| Table 1: Referring patients with sport and physical activity related injuries to specialists | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional | Qualifications | Referral pathway | Appropriate for |

| ‘Sports doctors’ | Includes orthopaedic surgeons, physicians or rheumatologists | NHS (via patient’s GP) | Ongoing, recurring, structural problems where surgery or longer term pain relief or disease modification is indicated |

| GP with special interest | Local accreditation recognises specialist training in sports medicine but maintains generalist role — often holds a Diploma or MSc in sports medicine | Usually private practice, although may be accessible via NHS | Assessment where precise approach uncertain or where a mixture of physical, surgical, manipulative and pharmacological therapies require coordination and overview |

| Physiotherapists | Member of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapists (MCSP) and also Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) registered (regulatory body) — look for specialist interest in sports injuries | Some available through NHS, also private practice and private hospitals | For musculoskeletal assessment, appropriate forward referral or rehabilitation including physical therapy primarily. Some specialists offer injection or prescribing to assist management |

| Chiropractor | General Chiropractic Council | Usually private practice | Treatment will mostly include manipulation to correct altered joint positioning, often spinally focused |

| Osteopath | General Osteopathic Council | Usually private practice | Treatment often includes mobilisation and/or manipulation of joints/soft tissues to address mechanical issues found on assessment |

| Podiatrist | HCPC registered — look for specialist interest in sports injuries | NHS and/or private. Avoid foot care assistants as they are not podiatrists | Suitable for conditions where gait or postural problems are suspected. May offer gait or biomechanical analysis and orthotic production |

| Sports masseurs | May be unqualified — look for the letters FSMT, which indicates Fellowship of Sports masseurs and Therapists | Not applicable | Patient believes massage may be helpful (no explicit evidence indicating physiological benefit) |

Box 1: Pharmacists as athlete support personnel

Pharmacists have a role in advising athletes on the prohibited status of medicines used in sport. These are detailed in the annual prohibited list of methods and substances produced by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) (see additional resources). Athletes should be warned that over-the-counter (OTC) medicines and their ingredients may vary from country to country. Elite athletes must declare use of OTC medicines during anti-doping testing procedures. An excellent resource available to all healthcare professionals is GlobalDRO (see additional resources), which provides information about the prohibited status of medicines and their ingredients purchased in the United States, Canada, the UK, Japan and Australia.

Additional resources:

- Whyte G, Loosemore M, Williams C (eds.) ABC Sport and Exercise Medicine. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Global DRO

- Mottram DR and Chester N (Eds). Drugs in sport. 6th Edition. Routledge. 2014.

- World Anti-Doping Agency. The prohibited list international standard. 2016.

- Dynamic stretching warm up routine

Trudy Thomas is a clinical lecturer at Medway school of pharmacy and a locum pharmacist,David Mottram is professor of pharmacy practice at Liverpool John Moores University andColin Waldock is associate lecturer at the University of Kent.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Hospital Episode Statistics Online. Rise in sport injury cases reported in A&E. 2012. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/article/2087/Rise-in-sport-injury-cases-treated-in-AE (accessed June 2016)

[2] Nicholl JP, Coleman P & Williams BT. The epidemiology of sports and exercise related injury in the United Kingdom. Br J Sports Med 1995;29(4):232–238. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.29.4.232

[3] British Government Strategy Unit. Game plan: a strategy for delivering government’s sport and physical activity objectives. 2002. London: Cabinet Office.

[4] Akram S & Zaman H. Warts and verrucas: assessment and treatment. T he Pharmaceutical Journal 2015;294:7867. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2015.20068680

[5] Ho S-L & Walming N. Over-the-counter treatments for athlete’s foot. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2014;293:7822/3. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/learning/cpd-article/over-the-counter-treatments-for-athletes-foot/20065964.cpdarticle (accessed July 2016)

[6] Leigh R. An A to Z of foot pain for pharmacists. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2012. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/learning/learning-article/an-a-to-z-of-foot-pain-for-pharmacists/11093072.article (accessed July 2016)

[7] Bahr R & Holme I. Risk factors for sports injuries – a methodological approach. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:384–392. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.5.384

[8] Woods K, Bishop P & Jones E. Warm-up and stretching in the prevention of muscular injury. Sports Med. 2007;37(12):1089–1099. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737120-00006

[9] McHugh MP & Cosgrave CH. To stretch or not to stretch: the role of stretching in injury prevention and performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20:169–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01058.x

[10] International Association of Athletics Federations. Medical manual Chapter 9: soft tissue damage and healing. Available at: https://www.iaaf.org/about-iaaf/documents/medical (accessed July 2016)

[11] Nickless G & Davies R. How to take an accurate and detailed medication history. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2016;296:7886. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/learning/learning-article/how-to-take-an-accurate-and-detailed-medication-history/20200476.article (accessed July 2016)

[12] Physiopedia. Ottowa Ankle Rule. Available at: http://www.physio-pedia.com/Ottawa_ankle_rule (accessed August 2016)

[13] Physiopedia. Ottowa Knee Rules. Available at: http://www.physio-pedia.com/Ottawa_Knee_Rules (accessed August 2016)

[14] Patel DS & Adrian BA. Do NSAIDs impair healing of musculoskeletal injuries? Rheumatology Network 2011. Available at: http://www.rheumatologynetwork.com/articles/do-nsaids-impair-healing-musculoskeletal-injuries (accessed July 2016)

[15] Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1888–1899. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906173402407

[16] Singh P & Roberts MS. Skin permeability and local tissue concentrations of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs after topical application. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1994;268:144–151. PMID: 8301551

[17] Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H et al. Topical NSAIDs for acute pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;6:CD007402. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007402.pub3

[18] Connolly DA, Sayers SP & McHugh MP. Treatment and prevention of delayed onset muscle soreness. J Strength Cond Res 2003;17(1):197–208. doi: 10.1519/00124278-200302000-00030

[19] Cheung K, Hume PA & Maxwell L. Delayed onset muscle soreness: treatment strategies and performance factors. Sports Med 2003;33(2):145–164. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333020-00005

[20] Mason P. Thermotherapy and cryotherapy. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2014;292(7815/6):641. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2014.20065362

[21] Brukner P. Hamstring injuries: prevention and treatment—an update. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1241–1244. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094427

[22] Schmitt B, Tim T & McHugh M. Hamstring injury rehabilitation and prevention of reinjury using lengthened state eccentric training: a new concept. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2012;7(3):333–341. PMID: 22666648

[23] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Tennis elbow. Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/tennis-elbow#!scenario (accessed July 2016)

[24] Doherty C, Delahunt E, Caulfield B et al. The incidence and prevalence of ankle sprain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective epidemiological studies. Sports Med 2014;44(1):123–140. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0102-5

[25] van den Bekerom MPJ, Struijs P, Blankevoort L et al. What is the evidence for rest, ice, compression, and elevation therapy in the treatment of ankle sprains in adults? J Athl Train 2012;47(4):435–443. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.4.14

[26] Shelbourne KD & Nitz PA. The O’Donoghue triad revisited. Combined knee injuries involving anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligament tears. Am J Sports Med 1991;19(5):474–477. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900509

[27] Sweeting D, Parish B, Hooper L et al. The effectiveness of manual stretching in the treatment of plantar heel pain: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res 2011;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-4-19

[28] Tu P & Bytomski JR. Diagnosis of heel pain. Am Fam Physician 2011;84(8):909–916. PMID: 22010770