Getty Images

Transfer (or transition) of care (TOC) happens when responsibility for a patient’s care is passed from one professional, agency and/or location to another as their conditions and care requirements change. TOC most commonly occurs in the context of discharge from hospital to community settings (e.g., to the patient’s own home, care home or supported and sheltered accommodation), but it is also crucial during patient transfer between hospital wards (handover), to an intermediate care unit, and from the community into a hospital or care home.

There were 15.89 million people admitted into NHS hospitals during 2014–2015[1]

and the majority of these would have been prescribed medicines to improve their care. One study estimated that 60% of patients have three or more changes made to their medicines during a hospital stay[2]

. The TOC process, particularly to and from hospital, is associated with an increased risk of adverse drug events (ADEs): 30–70% of patients experience an unintentional change to their treatment or an error is made, due to lack of communication or miscommunication[3]

. Communication failures between practitioners, and practitioners and their patients, as well as gaps in patients’ medical and drug histories, can lead to preventable drug-related admissions at various stages of the medicines pathway[4]

.

Published reports have identified a number of issues concerning TOC. The Care Quality Commission (CQC), the independent regulator of all health and social care services in England, published a report in 2009 that identified patchy and inconsistent information from GPs on admission to hospital[5]

. An additional report published in 2011 by two independent UK charities, Age UK and The Health Foundation[6]

and a national survey of primary care trust patients in 2007 and 2008[7]

identified the following main issues concerning TOC:

- Untimely and inaccurate discharge information from the hospital to GPs[6]

; - Information about patients’ preferences and conditions that impact on medicines use is not being transferred when care home residents are admitted to hospital. In addition, inadequate information about changes to their medicines carried out in hospital results in conflicting lists between hospital consultant and GP[6]

; - Poor patient (and carer) engagement in discussions about their medicines and inadequate information provided about their medicines[6],

[7]

.

This article focuses on TOC in the context of frail older people because they occupy 70% of hospital beds[8]

, frequently move across care settings, take more medicines[9]

, and suffer more from ADEs than any other age group[10]

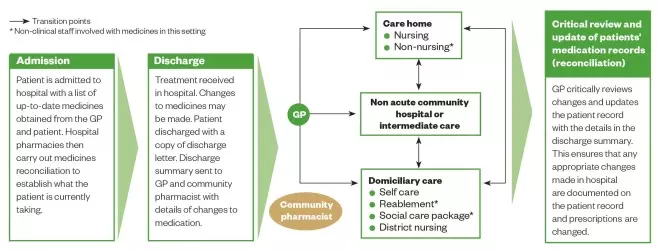

. They are more likely to be the subject of a complex discharge and have multiple individuals, including non-clinicians, agencies and teams involved with the management of their medicines, at several handover points (see Figure 1 for an example of a patient pathway).

Figure 1: Ideal patient pathway

Source: Adapted from Care Quality Commission. Managing patients’ medicines after discharge from hospital. National Study 2009

This pathway illustrates an older patient’s journey from hospital admission, through discharge and to home

Following hospital admission, changes in the patient’s functional status resulting from acute illness or new conditions (such as stroke, dementia, or fracture) should be communicated between healthcare professionals involved in immediate care, and to community based agencies and teams so the patient can get the support they need. While in hospital, closer monitoring of the effects of medicines may also be required while conditions and treatments are being stabilised. Often, many drugs initiated for acute symptoms (e.g., proton pump inhibitors, laxatives, analgesics, haloperidol, lidocaine patches) are continued long after the symptoms resolve, increasing the pill burden and risk of ADEs, factors which healthcare professionals should be mindful of.

When older people are transferred, the communication of accurate patient information between healthcare practitioners can lead to better patient outcomes and contribute to a reduction in polypharmacy, preventable medicines-related admissions and drug wastage. See Box 1 for an example of a patient whose condition worsened following poor communication.

Box 1: Case study – Poor communication results in a worsening eye condition

Following an eye operation, a 78-year-old female with a complex history of multiple eye conditions was prescribed six eye drop preparations, in addition to other medicines, and was subsequently discharged from hospital. Social care workers visited her at home three times daily to administer tablets and district nurses visited three times daily to administer eye drops. Outside these visits, the patient’s daughter helped with eye drops requiring more frequent administration and her other medicines.

Her daughter took her see to the hospital ophthalmology clinic each week where it was decided how her treatment would change in line with her progress. These changes were communicated to the daughter and patient verbally, but these conversations often led to confusion and disagreements with the nurses about what medicines should be taken. For example, at one appointment it was decided that levofloxacin drops would be taken beyond the seven days stated on the label; something that was not communicated to the district nurses or the patient’s GP. Because of this, the drops were not administered for several days, leading to the eye condition worsening.

The problem was resolved when the community clinical pharmacist contacted the hospital to explain the circumstances and to request that written information should be given to the patient and/or carer after each clinic visit.

Guidance

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), England’s health technology assessment body, has published medicines optimisation guidance (NG5)[11]

which builds on earlier publications by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), the membership body for pharmacy in Great Britain[12]

and the CQC[5]

. It places responsibility on commissioners and providers to ensure that robust and transparent processes are in place for safe and effective transfer of information at any point in the care pathway. While there are practicalities to consider and barriers to overcome (see Box 2), this should enable each practitioner involved in a patient’s care to have the information they need to prescribe, administer and monitor medicines safely and to continue evaluating their effects. NICE recommends four key principles for healthcare practitioners:

- The practitioner transferring care should send complete and accurate information about the patient’s medicines to the practitioner receiving care within 24 hours of the transfer. In addition, the transferring practitioner should consider sending the information to a nominated community pharmacy (see Box 2).

- The healthcare practitioner receiving care should check that the information has been received, then document and act on it.

- All practitioners should engage with patients and their carers or advocates as active partners in managing their medicines at the time of transfer. A complete list of medicines should be given to the patient/carer at the time of transfer with an explanation of why they are taking them, and when and how to take them, as well as a description of any changes made. The information provided should be personalised and in a format that is suitable for their needs. Those with complex requirements, e.g. receiving social care or end-of-life packages, should have a discharge plan that clearly states the arrangements that have been made to support them with taking medicines, and details of who to contact about medicine problems within 24 hours of discharge[13]

. - Information about patients’ medicines should be communicated in a way that is timely, clear and unambiguous. It should be generated and transferred in the most effective and secure way, preferably electronically.

Box 2: Barriers to implementing safe TOC in practice

Obtaining accurate and complete information:

- A robust system to notify community pharmacists that patients have been admitted to or discharged from hospital is not in place;

- Test results (e.g. renal function and/or international normalised ratio [INR] results) that are required to dispense, review and prescribe medicines safely are not readily accessible in community settings;

- Access to information on recent conditions or impairments that impact on the patient’s ability to adhere to medicines is limited. An exception is when contact is made to supply medicines in multi-compartment compliance aids (MCA);

- Current publications and guidance are centred on the transfer of information from the hospital to the GP practice or care home. Guidance is less clear, and the processes, referral and communication pathways less established, for transfer to other practitioners and organisations; those involved in re-ablement supported discharge and district nursing teams for example. In reality, some practitioners working within these teams are more likely to be the first to see patients after discharge. This can be problematic when they have to rely on patients with communication difficulties for a copy of the discharge summary;

- Challenges arise when undertaking medicines reconciliation when medicines are dispensed in MCAs.

Communicating information:

- Non-pharmacy staff may find it difficult to interpret abbreviations and acronyms related to medicines on discharge summaries: e.g. POSH (patients own supply at home) and POD (patient’s own drugs) indicate that the hospital has not supplied the drugs but may be interpreted in the community that those drugs have been discontinued;

- To have access to a patient’s summary care records, community pharmacists must obtain consent from the patient on every occasion (see ’How to use the summary care record in community pharmacy’ for more information). This can be challenging for some housebound older people or those patients with hearing difficulties and cognitive impairment.

Strategies and communication tools

Medicines reconciliation in the context of TOC is the process of identifying a complete and accurate list of a patient’s current medicines, comparing it with the admission or discharge list, and recognising and bringing any discrepancies to the attention of the prescriber, while documenting any changes to ensure that a complete list is accurately communicated. It should be undertaken by trained and competent healthcare professionals within 24 hours of transfer to an acute setting and as soon as practically possible in primary care, before a new supply for medicines is issued and within a week of the practice receiving the information. Communicating and taking action for any discrepancies is crucial and it is the practitioner’s responsibility to undertake reconciliation to clarify or pass on the necessary information so that medicines are used in a safe and effective way (see Box 3 for an example of a discrepancy in a discharge letter leading to rivaroxaban not being taken for four months).

Box 3: Case study – Poor transfer of information and lack of follow-up resulted in prescribed rivaroxaban not being taken for four months.

A housebound 80-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation and hypertension was prescribed rivaroxaban a while ago. Following a routine outpatient visit to an older people assessment unit (a multidisciplinary team of older care specialist doctors, nurses and therapists that receive referrals to help patients over the age of 65 years with issues that may be affecting their independence and well being) rivaroxaban was inadvertently omitted from the discharge letter. On receiving her next repeat medicine prescriptions, the patient rang her local pharmacist to query the absence of rivaroxaban. The pharmacist contacted the GP practice who suggested that the drug must have been stopped by the hospital, and so a query was noted in the patient’s records. At her next hospital appointment, three months later, the patient was identified as having problems adhering to her medicines and was referred to a pharmacist for a domiciliary medication review. The discrepancy was finally picked up during medicines reconciliation and after several phone calls, the patient was restarted on rivaroxaban after four months.

The ‘minimum dataset’ for discharge summaries should be consistent with the standard issued by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AOMRC), the body that speaks on standards of care and medical education across the UK[14]

. Ideally the discharge summaries should be sent electronically or given to the patient as a printed copy, and NICE recommends that it should include[8]

:

- Patient and GP contact details;

- Details of other relevant contacts (e.g. nominated community pharmacy);

- Known drug allergies and reactions;

- Current medicines (including non-prescribed); how and why they are taken;

- Changes to medicines and the reasons for them;

- Date and time of the last dose for weekly or monthly medicines;

- What information has been given to the patient or carers;

- Other necessary information; e.g., when to review, monitoring requirements, and support needed for adherence and for specific groups of patients, such as children.

Communication tools used to share information about patients’ medicines include:

- Discharge summaries: The RPS TOC toolkit showcases examples of initiatives and systems that utilise telephone, email, fax, and fully integrated electronic transfer of information from hospital to community pharmacies. Each method has its pros and cons and can be adapted to suit the locality[15]

. - Summary care record: An electronic patient care record which contains up-to-date information about patients’ medicines, adverse drug effects and allergies. It is a useful source of information that is readily accessible to community and hospital pharmacists. With patient consent, it can be viewed in emergency situations and out of hours. For more information on its implementation in community pharmacies, see the

Health and Social Care Information Centre’s website

[16]

and ‘How to use the summary care record in community pharmacy’

[17]

. - NHSmail: A secure email service approved by the Department of Health for sharing patient identifiable/sensitive information. It is available for use across organisations commissioned to deliver health and social care, including community pharmacists. For more information and how to obtain an account, see the Health and Social Care Information Centre’s website

[18]

. - Green Medicine Bag: A designated bag for transporting medicines between and around care settings to keep all the medicines belonging to a patient together in a readily identifiable bag. For more information, see the resources from NHS East & South East England Specialist Pharmacy Services

[19]

. - ‘Message in a bottle’: A record of people’s (particularly vulnerable people) basic personal and medical details, including a list of medicines written on a standard form. The form is kept in a bottle in the fridge in the patient’s home so it’s easily accessible to those involved in their care. For more information on the scheme and how to request supplies for community pharmacies, see

Lions Club International’s website

[20]

. - National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) oral anticoagulant therapy information booklet (formerly Yellow book) and

Steroid treatment warning card: A number of tools to share information with patients about their medicines are available in various formats; electronic and paper versions of patient held medication records are commonly used. These two tools are well known, but more recently, others have been developed to share information about the patient’s medicines in general. - My Medication Passport: This enables patients and their carers to keep an up-to-date list of their medicines and any changes in treatment in order to facilitate better communication with their healthcare professionals. It has been evaluated and is currently available as a pocket booklet and a downloadable smart phone application for both Android mobiles and iPhones[21]

. - My medicine, my choice, my record: A folded A4 sheet developed by the National Care Forum for care home residents to share information about their medicines and preferences with healthcare professionals. See The National Care Forum’s website for more information[22]

. - This is me: A document developed by the Royal College of Nursing, the UK’s largest union and professional body for nursing, and the Alzheimer’s Society, a UK dementia support and research charity, for people with dementia. Although it does not record the list of medicines, it provides information about the patient’s preferences (including how they take their medicines) that impact how they use their medicines. See the Alzheimer’s Society website for more information[23]

. - Predictive tools: For example, PREVENT can identify high-risk patients who may need tailored information and appropriate communication mechanisms to be put in place during transfer, or a referral for follow-up[24]

. This might include patients receiving social care and end-of-life packages, patients with Parkinson’s disease, and patients taking warfarin, insulin, and/or depot antipsychotics, where accurate and timely communication is particularly important. Pharmacy-led initiatives have shown a reduction in readmission rates by identifying high-risk patients and, at the point of discharge, undertaking medicines reconciliation and sending out timely discharge communications to the patients’ nominated community pharmacist, as well as contacting other relevant practitioners involved in their care for follow-up[25]

,[26]

. - The Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) tool: This was developed by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (now incorporated into NHS Improving Quality) and provides an easy way for practitioners to clarify what information needs to be communicated when making recommendations for another clinician’s immediate attention and action[27]

. It has been shown to improve the number of changes made to patients’ care plans and can be used in written or verbal communications. A video clip on how the tool may be used in community pharmacy can be viewed on the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement website

[28]

, and an example of the framework can be found in their resource[29]

.

Lelly Oboh is consultant pharmacist, care of older people, Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (Community Health Services) NHS Specialist Pharmacy services.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] NHS Confederation. Key statistics on the NHS. Available at: http://www.nhsconfed.org/resources/key-statistics-on-the-nhs (accessed May 2016).

[2] Himmel W, Kochen MM, Sorns U et al. Drug changes at the interface between primary and secondary care. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2004;42:103–109. doi: 10.5414/CPP42103

[3] National Patient Safety Agency and NICE. Technical patient safety solutions for medicines reconciliation on admission of adults to hospital. December 2007. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/psg1 (accessed May 2016).

[4] Howard R, Avery A & Bissell P. Error management. Causes of preventable drug-related hospital admissions: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:109–116. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.022681

[5] Care Quality Commission. Managing patients’ medicines after discharge from hospital. October 2009. Available at: http://www.cqc.org.uk/_db/_documents/Managing_patients_medicines_after_discharge_from_hospital.pdf (accessed May 2016).

[6] Age UK and The Health Foundation. Making care safer. Improving medication safety for people in care homes: thoughts and experiences from carers and relatives. June 2011. Available at: http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/MakingCareSafer.pdf (accessed May 2016).

[7] National Survey of PCTs’ patients in 2007/08.

[8] Audit Commission (2006), Living Well in Later Life: A review of progress against the National Service Framework for older people. London: Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection. Available at: http://www.scie.org.uk/publications/guides/guide15/files/livingwellinlaterlife-fullreport.pdf?res=true (accessed May 2016).

[9] The Information Centre for Health and Social Care. Prescriptions Dispensed in the Community, Statistics for England—2001–2011. 2012. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/searchcatalogue?productid=7930&q=title%3a%22Prescriptions+Dispensed+in+the+Community%22&sort=Relevance&size=10&page=1#top (accessed May 2016).

[10] Routledge PA, O’Mahony MS & Woodhouse KW. Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004;57:121–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01875.x

[11] NICE guidelines (NG5). Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. March 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 (accessed May 2016).

[12] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Keeping patients safe when they transfer between care providers – getting the medicines right. Final report. June 2012. Avaialble at: http://www.rpharms.com/current-campaigns-pdfs/rps-transfer-of-care-final-report.pdf (accessed May 2016).

[13] NICE guidelines (NG27). Transition between inpatient hospital settings and community or care home settings for adults with social care needs. December 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng27 (accessed May 2016).

[14] Health and Social Care Information Centre and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Standards for the clinical structure and content of patient records. July 2013. Available at: http://www.aomrc.org.uk/doc_view/9702-standards-for-the-clinical-structure-and-content-of-patient-records (accessed May 2016).

[15] Royal Pharmaceutcal Society. Hospital referral to community pharmacy: An innovators’ toolkit to support the NHS in England. December 2014. Available at: http://www.rpharms.com/support-pdfs/3649—rps—hospital-toolkit-brochure-web.pdf (accessed May 2016).

[16] Health and Social Care Information Centre. Summary Care Record (SCR) in community pharmacy. Available at: http://systems.hscic.gov.uk/scr/pharmacy (accessed May 2016).

[17] Gibson D & Smith L. How to use the summary care record in community pharmacy. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2016;296:7888 online. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20201008

[18] Health and Social Care Information Centre. NHSmail. Available at: http://systems.hscic.gov.uk/nhsmail (accessed May 2016).

[19] NHS East & South East England Specialist Pharmacy Services. Moving Medicines Safely: Implementing and sustaining a ‘Green Bag’ scheme (2013). Available at: http://www.medicinesresources.nhs.uk/upload/documents/Communities/SPS_E_SE_England/Moving_Meds_Safely_Imp_Green_Bag_Scheme_Vs2_Jan13_JH.pdf (accessed May 2016).

[20] Lions Club International. Lions Message in a Bottle (2014). Available at: http://lionsclubs.co/lions-message-in-a-bottle/ (accessed May 2016).

[21] Barber S, Thakkar K, Marvin V et al. Evaluation of My Medication Passport: a patient-completed aide- memoire designed by patients, for patients, to help towards medicines optimisation. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005608. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005608

[22] The National Care Forum. Resources for supporting the safe use of medications in care facilities. Available at: http://www.nationalcareforum.org.uk/medsafetyresources.asp (accessed May 2016).

[23] The Alzheimer’s Society. This is me. Available at: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=1604 (accessed May 2016).

[24] North West London Hospitals NHS Trust. PREVENT TOOL: high risk patient referral form. 2012. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/files/rps-pjonline/Simple%20Tools.pdf (accessed May 2016).

[25] Acomb C, Laverty U, Smith H et al. Medicines optimisation on discharge. The Integrated Medicines oPtimisAtion on Care Transfer (IMPACT) project. Int J Pharm Pract 2013;21:123–124.

[26] Barnett N & Blagburn J. Reducing preventable hospital readmissions: a way forward. Clinical Pharmacist 2016;8(1). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20200365

[27] National Health Service Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Safer Care, Improving Patient Safety. Available at: http://www.institute.nhs.uk/safer_care/safer_care/situation_background_assessment_recommendation.html (accessed May 2016).

[28] NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) escalation films. Available at: http://www.institute.nhs.uk/safer_care/safer_care/SBAR_escalation_films.html (accessed May 2016).

[29] NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) resource. Available at: http://www.institute.nhs.uk/images//documents/SaferCare/SBAR/Pads/SBAR_PrimaryCare_A5_AW.pdf (accessed May 2016).