AJD images / Alamy Stock Photo

With a prevalence of 1% of the UK population[1]

,[2]

, less than a quarter of individuals affected by coeliac disease receive a full clinical diagnosis[3]

. It is therefore estimated that there are more than half a million people with clinically undiagnosed coeliac disease in the UK. With many of these undiagnosed patients visiting community pharmacies, community pharmacists, their staff and other healthcare professionals can play a key role in identifying individuals with symptoms indicative of coeliac disease and can therefore refer them to their GP for testing and diagnosis.

A recent coeliac disease screening service piloted in the UK tested 551 patients and referred 52 (9.4%) patients to their GP for formal diagnosis[4]

. Using the same methodology, the actual detection rate for such a service provided through community pharmacy was predicted to be between 7% and 12%, which is significantly greater than the reported prevalence of 1%[1]

,[2]

. Over half of those patients screened were purchasing over-the-counter (OTC) remedies, such as loperamide and mebeverine for mild gastrointestinal symptoms, with the majority of the remaining patients collecting prescriptions for antispasmodics, mainly for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)[4]

.

The aim of this article is to raise awareness of the presentation of coeliac disease among primary care based pharmacists, their staff and other healthcare professionals, to enable the recognition of symptoms of the condition and provide sufficient information for healthcare professionals to be able to ask the right questions, in order to ensure appropriate advice and that a referral for formal diagnosis is made.

Background

A lifelong autoimmune disease, coeliac disease is caused by an adverse immune response to gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley and rye[5]

. In individuals with a genetic predisposition, a process occurs whereby there is enzyme modification of the gluten to produce immunological peptides. These peptides trigger immune cells to produce antibodies that cause damage to the villi (the finger-like projections in the lining of the gut [see Figure 1]). Consequently, the surface area for absorption of food is reduced and individuals suffer with malabsorption and resulting nutrient deficiencies (see Figure 2).

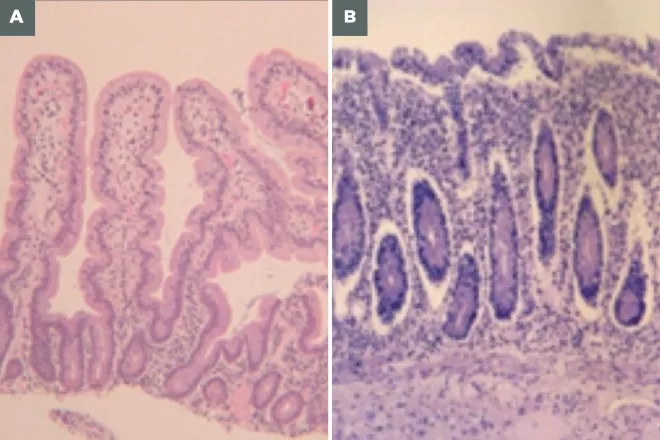

Figure 1: Normal villi and villi damaged by gluten

Source: Courtesy of Prof David Sanders

The surface of the jejunum is abnormally flat (panel B) due to the loss (atrophy) of villi, the small finger-like projections that increase the intestine’s surface area, due to the adverse immune response to gluten in patients with coeliac disease.

A) Micrograph of normal villi

B) Micrograph showing villi damaged by coeliac disease

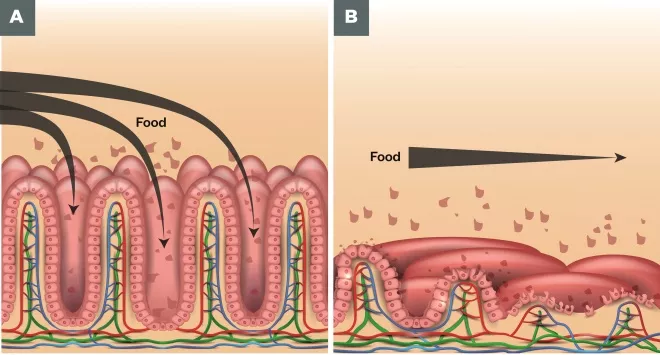

Figure 2: Food absorption in normal villi and in damaged villi

Source: Shutterstock.com

The loss of villi and surface area for absoprtion in patients with coeliac disease (panel B) can lead to the malabsorption of nutrients from food and as well as mineral and vitamin deficiencies in these patients.

A) Food absorption in normal villi

B) Food absorption in damaged villi

The characteristic symptoms associated with coeliac disease include bloating, diarrhoea, constipation, abdominal pain and cramping, wind, nausea, unexpected weight loss (but not in all), unexplained anaemia, extreme fatigue, and severe or persistent mouth ulcers[6]

.

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is the skin manifestation of coeliac disease, affecting around 1 in 3,300 people and commonly manifests as a rash on the elbows, knees, shoulders, buttocks and face, with red, raised patches often with blisters[3]

.

The mean duration of symptoms before formal diagnosis of coeliac disease is 13 years[7]

, which may be attributed to the wide-ranging symptoms of similarity with other conditions and/or lack of awareness and recognition of coeliac disease among the public and healthcare professionals.

Delayed diagnosis and untreated coeliac disease can be associated with osteoporosis, ulcerative jejunitis, unexplained infertility, vitamin D deficiency, unexplained anaemia and, in rare cases, small bowel lymphoma[6]

. The costs to the NHS associated with undiagnosed coeliac disease include more frequent visits to the GP, receipt of either OTC or prescription medicines for symptomatic treatment, and increased tests and referrals for specialist review[8]

,[9]

. The cost to the patient with undiagnosed coeliac disease can be significant suffering and ill health. Patients who have been diagnosed with coeliac disease and adopt a gluten-free diet report greater quality of life compared with pre-diagnosis and a similar quality of life to people who are not coeliac[7]

,[10]

. With the symptoms of coeliac disease being similar to those of many minor gastrointestinal conditions, patients are more likely to discuss them initially with their pharmacist rather than going directly to their GP[11]

.

While diarrhoea with associated gastrointestinal symptoms commonly occurs for a number of reasons, such as bacterial or viral infection and also as a result of dietary excess, it is the ongoing nature of these symptoms that sets coeliac disease apart from acute causes. Recurrence of comparable gut symptoms is also observed with other gut disorders including IBS and inflammatory bowel disorders (IBD). It is therefore perhaps not surprising that one in four people diagnosed with coeliac disease have previously been treated for IBS[12]

.

Screening and diagnosis

In 2009, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), England’s health technology assessment body, recommended that before confirmation of diagnosis of IBS, all patients should be screened for coeliac disease[13]

. Patients presenting at a community pharmacy with IBS who have not been tested for coeliac disease should be referred back to their GP for testing.

Based on current evidence, the UK National Screening Committee does not advocate systematic population screening for coeliac disease[14]

but supports the NICE recommendation of targeted screening of individuals at risk who have related symptoms or associated conditions[6]

. Individuals at risk should be offered serological tests for both total immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgA tissue transglutaminase antibodies (IgA tTGA). Total IgA levels are required because around 2–3% of patients with coeliac disease will have an IgA deficiency[15]

,[16]

and, therefore, if IgA tTGA is tested in isolation, these people will have a risk of false-negative results. It is recommended that patients with a positive serological test result are referred to a gastroenterology specialist for endoscopy with biopsy[6]

.

In the community pharmacy case finding study, the point-of-care test for coeliac disease was offered free of charge, but there is currently no financial model to provide these tests as part of a pharmacy-led NHS screening service[4]

. The NHS applies a NICE care pathway in the recognition, diagnosis and management of coeliac disease recommending referral to the GP and testing in primary care. The cost to patients for the individual point-of-care test is around £30, which is unlikely to be taken up by many patients[4]

.

Role of community pharmacy

The most common symptoms reported in the community pharmacy study for the early recognition of coeliac disease were abdominal problems (51.9%), general gastrointestinal symptoms (43.7%), regular diarrhoea (36.1%), prolonged fatigue (26.5%), regular and unexplained anaemia (11.1%), sudden or unexplained weight loss (3.4%), and regular and severe mouth ulcers (3.4%)[4]

. The presence or reporting of any of these symptoms by patients to pharmacists should act as a ‘flag’ to consider the likelihood of coeliac disease.

The proof-of-concept study was useful in highlighting the potential for targeting individuals at increased risk of coeliac disease presenting in community pharmacies for treatment of symptoms and conditions associated with undiagnosed coeliac disease[4]

. It further highlights the important role of pharmacists and other healthcare professionals in screening and the need for increased awareness of symptoms and appropriate advice to enable earlier recognition and diagnosis.

Box 1 summarises the symptoms and conditions where testing for coeliac disease should be advised, and highlights that patients who seek treatment for recurrent diarrhoea or for IBS and have not already been tested for coeliac disease should be referred. First-degree relatives of patients diagnosed with coeliac disease are also at an increased risk of developing the condition. The prevalence in first-degree relatives is one in 10 compared with one in 100 in the general population[6]

.

Box 1: Symptoms and conditions which should trigger testing for coeliac disease

Conditions

- Irritable bowel syndrome (and not previously tested for coeliac disease);

- Unexplained anaemia (iron, vitamin B12 or folate);

- Type 1 diabetes;

- Autoimmune thyroid disease.

Symptoms

- Recurrent diarrhoea;

- Constipation;

- Abdominal pain and cramping;

- Nausea;

- Wind and bloating;

- Unexplained weight loss (not in all cases);

- Extreme fatigue;

- Severe or persistent mouth ulcers.

Obtaining the required information from patients prior to referral

Community pharmacies are increasingly being used to provide screening services because patients like them, they have extended opening hours, tend to be accessible because they are geographically well distributed, and because trained healthcare staff are available [17]

,[18]

,[19]

. With access to summary care records and patient medication records, community pharmacists are in a position to identify individuals treated for symptoms and conditions that may indicate coeliac disease. The recent availability of reliable point-of-care tests[20]

enables community pharmacies to offer and undertake screening for coeliac disease[4]

, with the potential to reduce time to diagnosis and improve the use of health system resources. However, the cost-effectiveness of this approach is not established and unless the cost of such delivery is significantly less than through medical practices, it is unlikely that community pharmacies will be able to develop this model further.

Until screening for coeliac disease through community pharmacies becomes established practice it is important for community pharmacists, their staff and other healthcare professionals to be aware of the patients at greatest risk of coeliac disease. Open questions to determine the nature and frequency of symptoms, combined with knowledge of age of first appearance can provide the information required to enable appropriate referral to GPs.

Table 1 provides an outline of the information that needs to be obtained by pharmacists, their staff and other healthcare professionals in order to decide whether patients should be referred for testing. With significant overlap with other conditions such as IBS and IBD it is unrealistic for a community pharmacist to determine the cause of recurrent GI symptoms. If there is a possibility a patient could have coeliac disease, they should be referred. It is important to inform patients referred to their GP for testing for coeliac disease to not remove foods containing gluten from their diet at this stage or until diagnosis is completed. The serological test for coeliac disease is based on measuring the antibodies produced in response to eating gluten and if gluten has been removed from the diet there is a risk of a false-negative result.

| Table 1: Information required to enable identification of patients at risk of coeliac disease | |

|---|---|

| Information required from patient | Rationale |

| Weight loss | Persistent non-absorption of fats and nutrients due to coeliac disease may result in weight loss |

| Appearance of stool | Light, fatty and foul smelling stools commonly associated with reduced fat absorption |

| Duration | Prolonged duration suggested undiagnosed pathology such as coeliac disease |

| Recurrence | Due to gut inflammation which will not heal until foods containing gluten are removed from the diet |

| Presence of fatigue | resulting from malabsorption and resulting nutritional deficinecies, including anaemia and therefore commonly associated with coeliac disease |

Coeliac disease is a condition that is relatively simple to treat, resolution of symptoms can provide significant health benefits and referral for screening should not cause undue concern for patients.

- On 14 March 2017, we replaced the images in Figure 1 to better depict normal and damaged villi.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Bingley PJ, Williams AJ, Norcross AJ et al. Undiagnosed coeliac disease at age seven: population based prospective birth cohort study. BMJ 2004;328(7435):322-333. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7435.322

[2] West J, Logan RF, Hill PG et al. Seroprevalence, correlates and characteristics of undetected coeliac disease in England. Gut 2003;52(7):960-965. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.960

[3] West J, Fleming KM, Tata LJ et al. Incidence and prevalence of celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis in the UK over two decades: population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109(5):757-768. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.55

[4] Urwin H, Wright D, Twigg M et al. Early recognition of coeliac disease through community pharmacies: a proof of concept study. Int J Clin Pharm 2016;38(5):1294-1300. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0368-4

[5] Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med 2012;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-13

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NG20 Coeliac disease: recognition, assessment and management. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng20?unlid=20217684220161015201826 (accessed March 2017).

[7] Gray AM, Papanicolas IN. Impact of symptoms on quality of life before and after diagnosis of coeliac disease: results from a UK population survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:105. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-105

[8] Ukkola A, Kurppa K, Collin P et al. Use of health care services and pharmaceutical agents in coeliac disease: a prospective nationwide study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-136

[9] Violato M, Gray A, Papanicolas I et al. Resource use and costs associated with coeliac disease before and after diagnosis in 3,646 cases: results of a UK primary care database analysis. PloS One 2012;7(7):e41308.

[10] Paavola A, Kurppa K, Ukkola A et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life in screen-detected celiac disease. Dig Liver Dis 2012;44(10):814-818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041308

[11] Pharmacy Research UK. Community pharmacy management of minor illness; the MINA study. 2014. Available at: http://pharmacyresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/MINA-Study-Final-Report.pdf (accessed March 2017)

[12] Card TR, Siffledeen J, West J et al. An excess of prior irritable bowel syndrome diagnoses or treatments in Celiac disease: evidence of diagnostic delay. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013;48(7):801-807. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.786130

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). CG86 Recognition and assessment of coeliac disease. 2009. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg86 (accessed March 2017)

[14] UK National Screening Committee. The UK NSC recommendation on coeliac disease screening in adults 2014. 29 January 2016. Available at: http://legacy.screening.nhs.uk/coeliacdisease (accessed March 2017)

[15] Cataldo F, Marino V, Bottaro G et al. Celiac disease and selective immunoglobulin A deficiency. J Pediatr 1997;131(2):306-308. PMID: 9290622

[16] Chow MA, Lebwohl B, Reilly NR et al. Immunoglobulin A deficiency in celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012;46(10):850-854. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31824b2277

[17] Lindsey L, Husband A, Nazar H et al. Promoting the early detection of cancer: a systematic review of community pharmacy-based education and screening interventions. Cancer Epidemiol 2015;39(5):673-681. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.07.011

[18] Taylor J, Krska J, Mackridge A. A community pharmacy-based cardiovascular screening service: views of service users and the public. Int J Pharm Pract 2012;20(5):277-284. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2012.00190.x

[19] Willis A, Rivers P, Gray LJ et al. The effectiveness of screening for diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk factors in a community pharmacy setting. PLoS One 2014;9(4):e91157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091157

[20] Mooney PD, Kurien M, Sanders DS. Simtomax, a novel point of care test for coeliac disease. Expert Opin Med Diagn 2013;7(6):645-651. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2013.836179