Tabletalkmedia

Each community pharmacy will encounter around 32 newly diagnosed patients with cancer every year[1]

. This number is likely to increase over the coming years, since half the number of people born after 1960 will have cancer at some point in their lives[2]

.

The Independent Cancer Taskforce has set a target that 57% of patients with cancer will survive for ten years or more by 2020, with 75% surviving for one year[3]

. Evidence suggests that the earlier cancer is diagnosed, the more options are available for treatment and the greater the chance of survival[4]

. The ‘Be clear on cancer’ and ‘One you’ campaigns are part of this strategy[5]

and pharmacy teams should be familiar with these.

The potential role of community pharmacy teams in patient engagement around cancer ‘red flags’ and early diagnosis has been described in a study of 32 community pharmacies in the north of England[6]

. A total of 257 cancer alarm symptoms were raised by patients over a three-month period, providing evidence that each pharmacy will routinely encounter such patients[6]

.

While pharmacy teams will likely come into contact with patients across all stages of the cancer pathway, the first two principles of the 2015 NHS cancer strategy implementation plan, ‘prevention and public health’ and ‘earlier diagnosis’[3]

, are particularly relevant to pharmacy teams in order to identify patients with potentially undiagnosed cancer and refer them promptly to the relevant healthcare professionals.

Raising awareness

Pharmacy teams can raise public awareness of cancers and their causes, and play a part in improving prevention and early detection of cancers[7]

. The practicalities of training pharmacy teams to provide this and examples of five such schemes are described in the ‘Accelerate, coordinate and evaluate’ programme report[8]

.

Several national initiatives can be used as a basis to help pharmacy teams engage with and inspire their patients to initiate conversations (see Box 1)[9],[10]

,[11]

.

The WWHAM pharmacy patient questioning process is a good starting point because it can provide relevant answers[12],[13]

:

- Who is the medicine for?

- What are the symptoms?

- How long has the patient had the symptoms?

- What action has been taken already?

- Are they taking any other medication?

These initiatives, along with the accessibility of pharmacy by locality and without appointment[4]

, and the opportunity to see patients who may not routinely see another healthcare professional, means that community pharmacy teams with knowledge of red flags can help with earlier diagnosis of cancer[1]

.

Box 1: Initiatives to help pharmacy teams to engage with patients

- ‘Making every contact count’ by Public Health England[9]

This initiative employs the use of open-dialogue questioning. Ask ‘what’ and ‘how’, and give the patient time to talk through their own barriers, which is often a quicker process than a conversation skirting around the issue. Avoid giving your own experiences or statements and guide the patient to conclusions using the ‘SMARTER’ (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound, evaluated and recognised) objective setting that enables opportunities for follow up.

- ‘The whites of your eyes’ by the National Pharmacy Association

[10]

A campaign that capitalises on pharmacy’s vital role in face-to-face care in an increasingly threatening online environment. Identification of red flag cancer symptoms provides a perfect example of where opportunistic face-to-face intervention and assessment can be of benefit.

- Healthy Living Pharmacies[11]

This framework encompasses the ethos that pharmacy teams will display information to encourage and inspire conversations with their customers about lifestyle and health issues. This presents opportunities to promote screening and prevention through tobacco, obesity, alcohol and ultraviolet risk awareness. Cancer Research UK in particular has a wide range of leaflets on this topic. Local facilitators are also available to help.

Opportunities to engage and identify individuals arise through purchase of over-the-counter medicines, patients seeking advice on their symptoms and ailments, and indirect conversation through, for example, healthy living information. An increasing number of young people are developing mouth cancer owing to behavioural choices, such as smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, and too many people believe they are not at risk. This presents an ideal opportunity for pharmacy intervention[14]

.

As people see that cancer is treatable and health risk factors are communicated to them effectively, it may encourage them to discuss small but potentially important changes with pharmacy teams and other healthcare professionals[15]

.

However, pharmacy teams should have relevant knowledge of the signs and symptoms of different cancers and current screening programmes.

Red flag identification

Red flags can be described as an alarm or warning signs and symptoms that suggest a potentially serious underlying disease, such as cancer[3]

. A practical guide to red flag symptoms necessitating referral can be found in Table 1[16]

and non-specific symptoms in Box 2.

Several factors should be considered when examining the clinical features that help to identify a symptom as a red flag. These include:

- Duration — when do harmless symptoms become red flags?

Clinical complaints such as cough, tiredness or diarrhoea are common in acute, self-limiting viral illnesses but can transform into red flag symptoms should they persist. The precise period varies, but the upper limit is usually around 4–6 weeks;

- Demographics — age is an important determinant of cancer risk.

Symptoms that are viewed as red flags in older age groups may be more likely to be caused by other diagnoses in younger age groups where that particular type of cancer is rare. Table 1 demonstrates how age is applied to the interpretation of symptoms as red flags;

- Clinical features — anything presenting as ‘not normal’ for the patient should be considered.

For example, a lump (in particular lymph nodes — lymphadenopathy) or mass, a mucosal abnormality (in particular, oral or rectal), unexplained bleeding (in particular, vaginal, rectal or bruising).

| Table 1: Red flag symptoms necessitating referral | |

| Source: suspected cancer guidelines based on the Quick Reference Guide for Pharmacists 2017[16] | |

| Lung | Age 40 years and over with:

|

| Oral [14] |

|

| Upper gastrointestinal |

Age 55 years and over with:

|

| Lower gastrointestinal |

|

| Skin moles | Any age:

|

| Renal tract | Age 45 years and over with:

|

| Head and neck |

Age 45 years and over with:

|

| Breast |

|

Certain combinations of symptoms, including non-specific symptoms (see Box 2), require special attention — for example, an older patient with tiredness, weight loss and unexplained bleeding. The general rule to follow is that if a symptom persists, even if tests are shown to be negative, re-referral should be considered[4]

. Often a serious diagnosis such as cancer is not suspected until symptoms persist or worsen. Patients need to be encouraged to present to their GPs if they have persistent worrying symptoms to avoid late presentations and diagnoses in A&E[17]

.

Box 2: Non-specific symptoms

- Unexplained bleeding (rectal, vaginal, bruising);

- An unusual lump or swelling anywhere on the body;

- A sore that does not heal — skin or surface symptoms;

- Unexplained weight loss;

- Very heavy night sweats;

- An unexplained pain or ache;

- Appetite loss;

- Fatigue;

- Pruritis.

When to refer

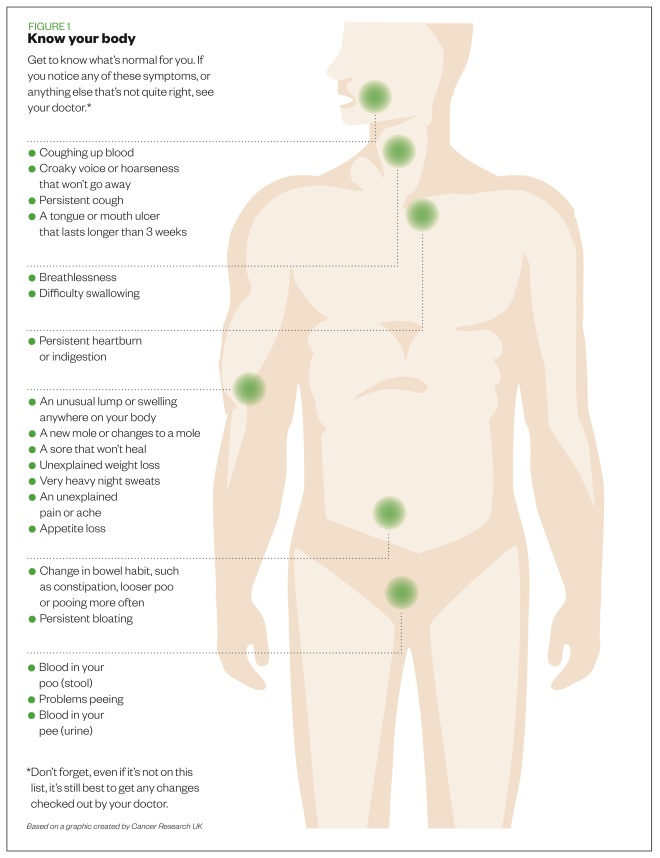

A useful tool to have in the pharmacy for patients is the Cancer Research UK (CRUK) guide ‘Spotting cancer early saves lives’, which has a section on ‘Know your body’ (see Figure 1)[18]

. Pharmacy teams must also be aware of and educate patients to recognise the general red flag symptoms shown in Table 1, some of which include unexplained weight loss and excessive tiredness.

Figure 1: Early warning signs of cancer

Source: Cancer Research UK

Macmillan Cancer Support produced a summary of the recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance on recognising suspected cancer and making referrals that provides additional accessible commentary for all members of the pharmacy team[19]

.

The main dilemma for pharmacy professionals is knowing whether a symptom necessitates referral. Pharmacy teams should be encouraged to refer when a symptom is not normal for the patient and when symptoms do not go away. In the author’s experience working in Devon, GPs provided positive encouragement to community pharmacy teams to help them identify undiagnosed patients at recent training sessions.

Ensuring referral happens

It is important to minimise patient fears but provide support to achieve referral. Support can be offered by addressing appointment barriers, asking patients to let you know how they got on, and helping them to have a meaningful conversation with their GP by writing down worrying symptoms and what may aggravate or relieve those symptoms.

Analysis of the ‘Be clear on cancer’ campaigns showed that public awareness of symptoms and reporting appears to be increasing[20]

. It is important to overcome potential rejection of referral advice leading to lack of attendance by patients at any stage in the diagnostic process. A different approach may be needed to change public perception of GP approachability (see Box 3). Work has been carried out to assess and quantify these barriers[21]

.

Pharmacy professionals should reinforce the message by ensuring the patient does not delay going to see their GP about their ‘worrying symptoms’. Conversational tips to engage the patients and attempt to overcome barriers are outlined in Box 4. Talking through these barriers is helped with using the questioning processes previously described (e.g. WWHAM).

Awareness of the behaviour change cycle and patient beliefs about their health is important to any discussion. For example, your patient may believe their health is under the control of outside influences rather than being caused by their own actions. These patients are said to have an external locus of control[22]

. They may feel they are immune to cancer (e.g. “it couldn’t happen to me” belief) or that their health is the responsibility of healthcare professionals (e.g. “I will wait until my next mammogram and ask them about this lump”). They may have progressed from this to the start of the change cycle and feel they should do something about their symptom but have not done so yet.

Box 3: Barriers to seeing the GP about worrying symptoms

- Embarrassment;

- Perception of wasting the GP’s time;

- Fear;

- Worries about what the doctor might find;

- Difficulty in making an appointment;

- Apparent immunity (e.g. “it couldn’t happen to me” belief);

- Responsibility is that of the healthcare professional (e.g. “my doctor has not said anything”);

- Low perceived risk (around 2–3% of cancer is caused by inherited genes);

- Ignorance — one in five people remain unaware of mouth cancer[14]

.

Source: Cancer Research UK

[23]

Box 4: Conversational tips

- Encourage conversation by displaying relevant materials, such as those explaining how lifestyle decisions (e.g. alcohol, smoking, obesity, diet and sun exposure) contribute to cancer

[23]

; - Think about how you would feel if your patient developed cancer from a lifestyle choice that you could have warned them about;

- Myth busting — there is no evidence to show that mobile phones, deodorants and stress increase the risk of cancer or that ‘superfoods’ prevent or cure cancer[24]

; - You do not need to have answers; help is readily available from the voluntary sector. Ensure you use reliable sources of information, such as NHS Choices, Cancer Research UK and Macmillan Cancer Support. Be aware of the variety of tumours patients can have; there is a range of reliable sources of information and support for patients with different cancers;

- Work with pharmacy colleagues to identify main points to raise when having conversations about cancer. Try questions that do not mention cancer[6]

, such as:- What does your doctor say about that?

- How long have you had it?

- What has changed?

- What is it you are worried about?

Screening processes

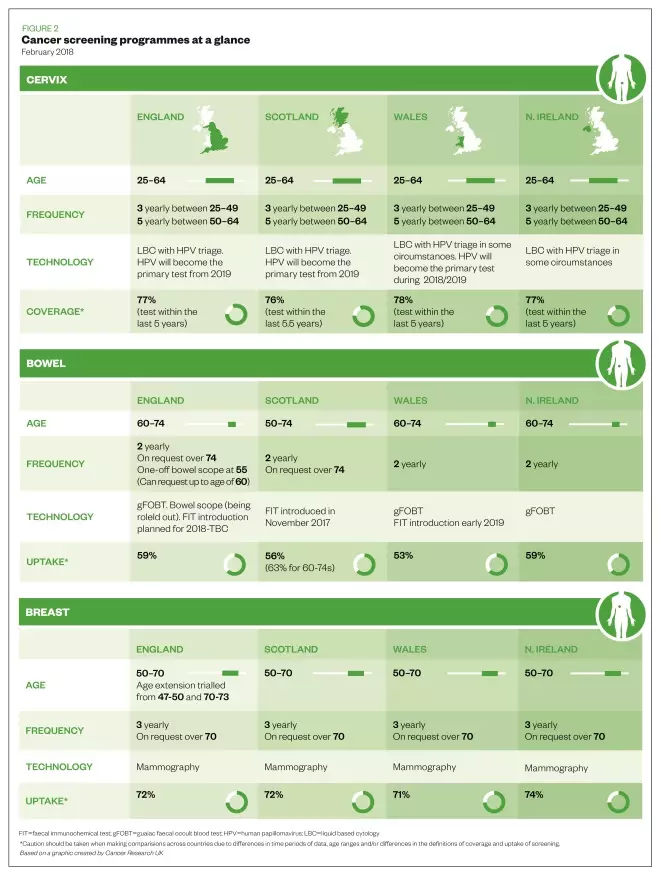

National screening programmes are offered to several age groups for breast, bowel and cervical cancer (see Figure 2)[25]

. Patients should be encouraged to attend screening. The CRUK ‘Talk cancer’ team highlights that some screening processes prevent cancer by detecting abnormal cells before they develop into cancer, including cervical cancer screening and the new bowel scope screening process.

Figure 2: Cancer screening programmes at a glance

Source: Cancer Research UK

Other screening processes for breast cancer and stool sample collection for bowel screening pick up cancers at an early stage, enabling treatment to be more successful. Pharmacists should ensure they have a conversation about screening where possible, as pharmacy teams have a vital role in encouraging self-examination and screening uptake.

Pharmacy teams can use strategies outlined in national initiatives which are simple to use, together with reliable information and support to alleviate fear and encourage early referral and screening to improve outcomes. If pharmacy staff are confident to engage with patients, they can elicit and overcome patient barriers with the use of relevant information and encourage prompt referrals.

Useful resources

- Bowel cancer and the ‘Blood in pee’ campaign

- ‘Suspected cancer guidelines for pharmacists’

- ‘Talk cancer’ (a free online course) run by Cancer Research UK

- Macmillan Cancer Support primary care resource pack

- ‘Accelerate, coordinate, evaluate programme: Pharmacy training for early diagnosis of cancer’

- The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s quick reference guides:

References

[1] Lewis J. How to support cancer patients in community pharmacies. Pharm J 2017. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2017.20202377

[2] Cancer Research UK. Spot cancer early. 2016. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-symptoms/spot-cancer-early (accessed October 2018)

[3] NHS England. Cancer strategy implementation plan. 2016. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/strategy/ (accessed October 2018)

[4] Jones D & Macleod U. Recognition and referral of cancer symptoms in primary care. Practice Nursing 2015;26(9):426–431. doi: 10.12968/pnur.2015.26.9.426

[5] Public Health England. Be clear on cancer. 2017. Available at: https://campaignresources.phe.gov.uk/resources/campaigns/16-be-clear-on-cancer (accessed October 2018)

[6] Badenhorst J, Husband A, Ling J et al. Do patients with cancer alarm symptoms present at the community pharmacy? Int J Pharm Pract 2014;22(Suppl 2):23–106. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12146

[7] Gill J, Sullivan R & Taylor D. Overcoming cancer in the 21st century [lecture/presentation]. UCL School of Pharmacy. January 2015.

[8] Cancer Research UK, NHS England & Macmillan. Pharmacy training for early diagnosis of cancer. Accelerate, Coordinate, Evaluate (ACE) Programme. 2015. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/ace_pharmacy_training_report_june_2017_update.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[9] NHS England. Making every contact count. 2016. Available at: http://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/ (accessed October 2018)

[10] National Pharmacy Association. The whites of your eyes. 2017. Available at: https://www.npa.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Whites-of-your-eyes-article-June-2017.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[11] Royal Society for Public Health. Healthy Living Pharmacy. Available at: https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-services/registration-healthy-living-pharmacies-level1.html (accessed October 2018)

[12] Randall M & Neil K. The patient: Signs and symptoms. Disease Management 2016. Pharmaceutical Press. London. P4.

[13] Training Matters. Getting the most out of WWHAM. 2015. Available at: https://www.tmmagazine.co.uk/getting-the-most-out-of-wwham (accessed October 2018)

[14] Pharmacy Magazine. Oral health: could it be cancer? 2018. Available at: https://www.pharmacymagazine.co.uk/could-it-be-cancer (accessed October 2018)

[15] Schroeder K, Chan W & Fahey T. Recognizing red flags in general practice. InnovAiT 2011;4(3):171–176. doi: 10.1093/innovait/inq143

[16] Devon Local Pharmaceutical Committee. Suspected cancer guidelines — quick reference guide for pharmacists. 2017. Available at: https://psnc.org.uk/devon-lpc/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2017/07/Suspected-Cancer-Guidelines-for-pharmacists-docx.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[17] National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service. Routes to diagnosis: exploring emergency presentations. 2013. Available at: http://www.ncin.org.uk/publications/data_briefings/routes_to_diagnosis_exploring_emergency_presentations (accessed October 2018)

[18] Cancer Research UK. Spotting cancer early saves lives. 2017. Available at: https://publications.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/publication-files/Early%20Diagnosis%20Female%20WEB.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[19] Macmillan Cancer Support. Rapid referral guidelines. 2015. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/documents/aboutus/health_professionals/pccl/rapidreferralguidelines.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[20] Power E & Wardle J. Change in public awareness of symptoms and perceived barriers to seeing a doctor following Be Clear on Cancer campaigns in England. Br J Cancer 2015;112(1):S22–S26. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.32

[21] Cancer Research UK. Delay kills. 2012. Available at: www.cancerresearchuk.org/prod_consump/groups/cr_common/…/cr_085096.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[22] Rotter JB. Social learning and clinical psychology. NY: Prentice-Hall. 1954.

[23] Cancer Research UK. Causes of cancer. 2012. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer (accessed October 2018)

[24] Cancer Research UK. Cancer controversies. 2015. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/cancer-controversies (accessed October 2018)

[25] Cancer Research UK. Screening for cancer. 2018. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/screening (accessed October 2018)