Royal Pharmaceutical Society

A host of legislative changes have been introduced in the UK since the Shipman Inquiry concluded in 2005, which are designed to improve controlled drug (CD) manageÂment. More information, including the definition of a CD, can be found in Box 1. The number of CD items being prescribed is decreasing[1],[2]

; however, this decrease does not take into account the quantities prescribed. There remain examples of poor management of opiates, in particular, and there is even more scrutiny of the use of these drugs following the events at Gosport War Memorial Hospital

[2]

. Pharmacists can develop and implement processes (e.g. reviewing existing CD documentation) to ensure guidance is being met.

There are also increasing numbers of non-medical prescribers issuing CD prescriptions[2]

. Pharmacists can review CDs to ensure that the prescription and length of treatment are appropriate for a patient’s condition, and can reduce opportunities for overprescribing and diversion. Furthermore, there is the potential to develop pharmacist-led clinics in both palliative care[3]

and pain management[4],[5],[6]

.

This article examines what pharmacists can do to ensure the safe use and management of CDs in secondary care. This article will not cover CD management in care homes (for more information, see the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] guidelines[7]

).

Box 1: What is a controlled drug?

By law, a controlled drug (CD) is any substance or product as specified in Schedule 2 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971[8]

. In practice, CDs are medicines that are subject to control under several pieces of legislation to prevent them being misused, obtained illegally or causing harm[9]

.

CDs are categorised into three classes — A, B and C. Class A drugs are considered most likely to cause harm and carry the most severe punishment for unlawful possession and supply: up to life imprisonment[1]

.

Healthcare providers in England, Wales and Scotland need to apply for a Home Office licence if they wish to produce, supply, possess, import or export CDs[10]

. A similar licence is required in Northern Ireland (issued by the Department of Health)[11]

. Generally, a hospital will only need a license to possess CDs unless they intend to also undertake wholesale dealing of CDs when a licence to supply is also required.

All designated bodies must appoint a controlled drugs accountable officer (CDAO) who is wholly responsible for the safe and legal management of CDs in line with Regulation 8 of the 2013 regulations[12]

(see Box 2). CDAOs must be a senior manager of board/director level who does not routinely prescribe, supply, administer or dispose of CDs as part of their duties[13]

.

When prescribing CDs it is important to take into account the risks and benefits of the CD, as well as any other medicines the patient may already be taking. The indication and regimen must be clearly documented on the patient’s care record. The quantity of the CD prescribed should be sufficient to meet the patient’s clinical need for no more than 30 days. However, if a larger quantity is prescribed, this should be documented in the patient’s care record. It is also important to provide patients and carers with information about the CD, including whether it affects their ability to drive or if they require identification to collect it[14]

.

Processes and record keeping

As a minimum, all secondary care facilities must have a robust overarching CDs policy in addition to risk-assessed, task-specific standard operating procedures (SOPs). This should include SOPs for the processes listed in Box 2, although it should be noted that this list is not exhaustive. The NICE guidelines include a useful baseline assessment tool for organisations to assess whether they are meeting the recommendations[14]

.

Box 2: Task-specific standard operating procedures that should be present in facilities with controlled drugs

Storage

- For pharmacy and clinical areas, including theatres and ambulatory services (e.g. paramedics, doctors’ bags and midwives’ bags). This should include processes for environmental monitoring, review of security (in particular key security) and segregation of high-strength stock, patient’s own controlled drugs (CDs) and expired CDs.

- For example, CDs must be stored in a cabinet or safe that is locked with a key. It should be made of metal, with suitable hinges and fixed to a wall or the floor with rag bolts that are not accessible from outside the cabinet[15]

.

- For example, CDs must be stored in a cabinet or safe that is locked with a key. It should be made of metal, with suitable hinges and fixed to a wall or the floor with rag bolts that are not accessible from outside the cabinet[15]

Transport

- The movement of CDs to and from the pharmacy department. Risk assessments should be undertaken to determine people authorised for CD transportation. Assessments should also be made for actions required during temporary and permanent ward closure. All movement of CDs must be fully auditable, including the return of CDs back to pharmacy and transfer between wards.

Destruction and disposal of CDs

- For both pharmacy and clinical areas. All facilities disposing of CDs must have a T28 waste exemption certificate issued by the Environment Agency. The records of and disposal of large volumes of part-used amps and infusions should be considered carefully. All care must be taken to ensure that they are not open to abuse; part-used amps/vials/infusions should have their contents withdrawn and denatured using absorbent granules (as part of a denaturing kit or added to a sharps bin).

- All destructions, whether at a clinical level or within pharmacy, need to be witnessed; however, stock CDs no longer fit for purpose can only be destroyed by an authorised witness (e.g. the police CD liaison officer or the facilities authorised witness for destruction, who needs to be registered with the Home Office and Care Quality Commission [as appropriate]).

Stock-checking processes

- There should be standard operating procedures (SOPs) about how to check stock and documentation based on a documented risk assessment of activity.

Prescribing processes

- There should be SOPs to ensure legality of prescriptions, safe prescribing practices, clear instructions and reduced opportunity for dependency, overdose and diversion.

Supplying and administering processes

- There should be SOPs to ensure requests for CDs are legal and volumes are appropriate. Processes should also be in place to ensure anyone requesting CDs or supplying or administering CDs are suitably trained and are authorised to do so.

- All supply and administering of CDs must be witnessed.

Audit provision

- There should be SOPs to monitor all operational processes, including review of prescribing trends and high-volume prescribing.

Providing medicines information

- There should be SOPs for how to inform patients (see Box 3), carers and healthcare professionals about CDs.

Raising concerns and sharing learning experiences

- There should be SOPs about how to raise concerns and share experiences both inside and outside the hospital facility or organisation.

Management of national medicines safety guidance

- For example, patient safety alerts to ensure alerts or new guidance and recommendations are reviewed and acted upon within an appropriate time frame.

Medicines, Ethics and Practice has the most up-to-date legal requirements for record keeping of CD transactions[16]

. At minimum, a separate CD register is legally required to be kept at all premises where CDs are stored[17]

, in which, all records of receipt and supply of Schedule 1 and 2 CDs are made (for Sativex® [GW Pharma Ltd, Bayer], a Schedule 4 Part 1 CD must also be recorded).

The registers are a legal document; therefore, entries must not be cancelled, obliterated or altered. If amendments are made, the register should be clearly documented to show which staff member made the amendments, with dated marginal notes or footnotes[16]

. CD registers must be kept for two years from the date of the last entry[17]

.

Requisitions for CDs, records of destruction and invoices must also be kept. Hospitals or facilities in secondary care who supply stock CDs to another facility that is not the same legal entity must now use the approved mandatory requisition form (except in the case of hospices or prisons)[16]

. Requisitions should be kept for a minimum of two years from the date on the request, while there is a recommendation to keep destruction registers for seven years and invoices for at least six years[14]

.

Audit of CD record keeping is essential to ensure legal requirements are being adhered to. Poor record keeping can lead to problems with fraud, diversion (i.e. removal of CDs for unauthorised use) and stock control. Box 3 describes a CD record keeping review within HCA Healthcare UK hospitals.

Box 3: Review of controlled drug record keeping in hospital

A multidisciplinary review of all current UK controlled drug (CD) legislation and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines regarding CD record keeping requirements was undertaken between April 2017 and September 2017 within HCA Healthcare UK hospitals. A number of changes were made to ensure best practice principles were standardised and adhered to. These included:

- The introduction of bespoke CD registers to incorporate clear management of errors (see Supplementary Figure 1);

- The introduction of a record of part-used infusions/syringe drivers disposal within the CD register (see Supplementary Figure 2);

- The introduction of a bespoke “patient’s own” CD register, CD transfer register and theatre/critical care CD register;

- Standardised balance/check log books were developed to ensure consistency in practice across the organisation.

Since the introduction of the new CD registers, there has been a significant improvement in CD documentation clarity and compliance with legal standards. Preliminary audit results show CD documentation non-conformances at 0% in the pilot site at The Christie Private Care facility in Manchester.

Source: HCA Healthcare UK. Audit data not published

Risk assessment of diversion potential

The Care Quality Commission has reported an increasing number of diversion or misuse incidents of CDs by healthcare professionals[2]

. Within pharmacy, a spike in requests for stock top-ups of codeine or requests for CDs by an unauthorised practitioner may raise suspicions of diversion and should be reported. Potential approaches to reducing the risk of diversion include:

- Use of automated medication dispensing systems at the bedside;

- Restricting the supply of Schedule 3 and 4 ward stocks (e.g. codeine, dihydrocodeine, zopiclone, diazepam) by having smaller stock holdings but more frequent pharmacy ‘top-ups’;

- Checking for discrepancies in stock balances at shift handover;

- Local reclassification to a more strictly controlled schedule (e.g. managing diazepam as a Schedule 2 CD, rather than Schedule 3, that must meet storage and register requirements);

- Close monitoring of repeat prescriptions.

Any approach to managing diversion must be appropriately risk assessed to ensure that it does not detrimentally impact patient safety or experience, and should be undertaken by a pharmacist with appropriate seniority alongside the controlled drugs accountable officer (CDAO).

All organisations must have clear processes for reporting CD-related incidents. In practice, concerns are usually raised with the reporter’s line manager and documented immediately via the organisation’s incident reporting system, while the CDAO has overarching responsibility for managing CD incidents and escalating concerns and learning outcomes outside the organisation where appropriate. This may include liaising with the CDAO’s Local Intelligence Network, the Care Quality Commission, the police or the NHS Counter Fraud Authority (formerly NHS Protect)[14]

. All healthcare professionals are required to raise concerns regarding diversion of CDs.

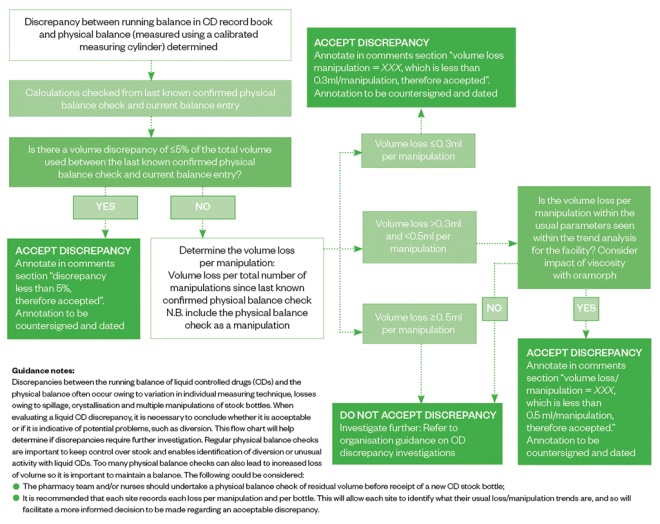

Management of liquid CD discrepancies

Stock control of liquid CDs is extremely difficult as loss of volume is inevitable when repeatedly manipulating a stock bottle of liquid. There is no formal published guidance dictating the value of an ‘acceptable loss’, although, anecdotally, many organisations adopt 5% of total volume as an acceptable loss.

However, this does not consider the number of manipulations made and so looking at the loss per manipulation may be a much more accurate measurement of loss, as the more manipulations, the greater the risk of loss owing to inaccurate measurements, spillage and residue formation. Across HCA Healthcare UK hospitals, any loss of >0.3mL/manipulation is flagged as a concern and any loss of >0.5mL/manipulation requires immediate investigation.

Other measures can help ensure the loss per manipulation is reduced (e.g. ensuring staff have access to suitable-sized enteral syringes, so they can use the smallest size possible to measure the volume required more accurately, and using bungs help reduce spillage). Regular physical balance checks enable identification of diversion; however, the number of checks should be limited because introducing too many may also contribute to losses. See Figure 1 for an example of how to manage liquid CD discrepancies.

Figure 1: Managing liquid controlled drug volume discrepancies — the HCA Healthcare process

Source: Source: Reproduced with permission from HCA Healthcare UK

Pharmacists have a responsibility to ensure the safe and secure management of CDs, both operationally and clinically. They must ensure that the necessary operational processes are regularly process mapped, risk assessed, and embedded via a sustainable programme of audit and sharing of lessons learnt, both within and outside their organisations. Simple changes, such as reviewing CD documentation or reviewing management of liquid CDs, can result in substantial improvements.

Operational standards should be adhered to and pharmacists should be aware of how CDs are managed within their area of responsibility, along with how to spot potential issues and how to report concerns regarding non-conformance or diversion via the appropriate channels. Clinically, pharmacists must take necessary steps to assure themselves that quantities prescribed are appropriate when dispensing prescriptions. Pharmacists should ensure all patients receive clear information on how to take their medication safely, including providing advice about driving and safe disposal at home.

References

[1] The National Archives. The Shipman Inquiry: Fourth report — the regulation of controlled drugs in the community. 2004. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20090808160142/http://www.the-shipman-inquiry.org.uk/fourthreport.asp (accessed September 2018)

[2] Care Quality Commission. The safer management of controlled drugs — annual update 2016. 2017. Available at: http://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20170718_controlleddrugs2016_report.pdf (accessed September 2018)

[3] Johnstone L. Facilitating anticipatory prescribing in end-of-life care. Pharm J 2017;298(7901). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2017.20202703

[4] News desk. Glasgow and Clyde engage pharmacy palliative care facilitators. Pharm J 2014;292(7795). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2014.11133559

[5] Valgus J, Jarr S, Schwartz R et al. Pharmacist-led, interdisciplinary model for delivery of supportive care in the ambulatory cancer clinic setting. J Oncol Pract 2010;6(6):e1–e4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000033

[6] Bellingham C. How pharmacists can help manage chronic pain in primary care. Pharm J 2002. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/pj-online-how-pharmacists-can-help-manage-chronic-pain-in-primary-care/20006090.article (accessed September 2018)

[7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Managing medicines in care homes. Social care guideline [SC1]. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sc1 (accessed September 2018)

[8] The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Misuse of Drugs Act 1971: Chapter 38, Section 2. 1971. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1971/38/contents (accessed September 2018)

[9] NHS Choices. What is a controlled medicine (drug)? 2015. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/chq/Pages/1391.aspx?CategoryID=73 (accessed September 2018)

[10] Home Office. Controlled Drugs: licenses, fees and returns. 2018. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/controlled-drugs-licences-fees-and-returns (accessed September 2018)

[11] Department of Health. Controlled drugs. 2015. Available at: https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/articles/controlled-drugs (accessed September 2018)

[12] Department of Health. The Controlled Drugs (Supervision of Management and Use) Regulations 2013. 2013. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2013/373/contents/made (accessed September 2018)

[13] Department of Health. Controlled Drugs (Supervision of Management and Use) Regulations 2013: Information about the regulations. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/214915/15-02-2013-controlled-drugs-regulation-information.pdf (accessed September 2018)

[14] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Controlled drugs: Safe use and management. NICE guideline [NG46]. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng46 (accessed September 2018)

[15] Department of Health. The Misuse of Drugs (Safe Custody) Regulations 1973. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1973/798/regulation/3/made (accessed September 2018)

[16] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Medicines, Ethics and Practice: The professional guide for pharmacists. 42 Ed. 2018. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/publications/medicines-ethics-and-practice-mep (accessed September 2018)

[17] Department of Health. The Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001. 2001. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2001/3998/contents/made (accessed September 2018)