Alex Baker

Dry eye is a particularly common ocular condition; prescribed treatments, which include artificial tears and lubricants, were dispensed at a cost of more than £27m to the NHS in England alone in 2014[1]

. Patients, typically with mild to moderate levels of dry eye, will often present to their optometrist or community pharmacist and are managed without the need for referral to their GP or an ophthalmologist. In a recent, unpublished survey by The Pharmaceutical Journal (see ‘Supplementary information’), over two thirds of community pharmacists reported speaking with patients about a dry eye condition more than once a week. Therefore, the cost of £27m does not include over-the-counter sales and the true economic burden of dry eye in the UK is unknown.

Initial patient presentation

When a patient presents with symptoms of a dry eye condition, such as irritation, grittiness, burning, soreness, watery eyes and visual disturbances generally affecting both eyes, a detailed history should be recorded by the pharmacist because it may elicit information about contributing factors[2]

. Briefly, this should include details of the signs and symptoms, duration of symptoms and exacerbating factors, such as the environment, changes in humidity or computer use. It should also record details of topical and systemic medicines taken by the patient, whether the patient wears contact lenses and if the patient has any dermatological, inflammatory or other systemic diseases. A differential diagnosis for other eye conditions (such as conjunctivitis, allergy and acute red eye) should be established because initial presentation may be similar.

For a more detailed explanation about identifying patients with dry eye conditions in a community pharmacy setting, please refer to this article: ‘Identification of dry eye in community pharmacy’

[3]

. At a meeting of dry eye experts held at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in London on 25 April 2016, a list of several pertinent questions were suggested that would help pharmacists with a differential diagnosis (see ‘Seven questions to ask a patient with suspected dry eye disease’).

Seven questions to ask a patient with suspected dry eye disease

- Is the dryness/burning/watering in both eyes?

- How long has it lasted?

- Do you have mouth dryness?

- Was it precipitated by an event?

- Are you in pain?

- Does your vision clear when you blink?

- Is there redness or swelling?

The main types of dry eye are aqueous deficiency, evaporative or a combination of the two. There is increasing evidence that meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), which causes evaporative dry eye, is the leading cause of dry eye[4],[5]

. There are no current UK national guidelines for the management of dry eye

[1]

, although local prescribing guidelines are available from a variety of NHS authorities, which typically recommend hypromellose as a first-line treatment[6],[7]

. However, treatment with artificial tears or lubricants alone can be unsuccessful, especially if other contributing factors are not appropriately managed[2]

. Treatment should take an aetiology-based approach and, given the wide variety of products available, this will enable individualised care[8]

.

Giving lifestyle advice

Patients experiencing intermittent or mild symptoms of dry eye can benefit from advice on management from a pharmacist. Initially, patients can be given appropriate lifestyle advice to try to reduce the symptoms of their condition. This includes: using humidifiers; stopping smoking; taking regular breaks from the computer to encourage blinking; ensuring the top of the computer monitor is at eye level to reduce the aperture width between the eyelids; and increasing dietary omega-3 fatty acid intake or oral supplementation[2],

[9]

,[10],[11]

.

Exogenous factors, such as taking medicines including antihistamines, diuretics and antidepressants, may also contribute to symptoms of dry eye. Patients with established comorbidities, such as blepharitis or MGD, should be advised of suitable lid hygiene and lid warming therapies (see ‘Managing blepharitis and MGD’). Once these potential causes and contributing factors to dry eye conditions have been initially addressed, treatment with artificial tears or lubricants may be indicated.

Tear supplementation

The ultimate goal of dry eye treatment focuses on symptomatic relief[9]

, usually using tear supplements. Despite this, the underlying mechanism of symptomatic improvement with tear supplementation is still poorly understood. It is thought that increased tear volume, improved tear stabilisation, reduced tear osmolarity or a dilution of inflammatory biomarkers or a combination of these factors play a vital role[12]

.

Topical ocular lubricants are the mainstay of dry eye treatment[12]

, with the choice of tear substitute depending on the severity of the condition[13]

. Pharmacological interventions in all forms of dry eye conditions range in formulation, such as drops, sprays, gels and ointments, with most available as either medical device products, general sales list (GSL) or pharmacy medicines (P).

Hydrogel polymers, such as those containing hypromellose or carbomer 980, can be effective in some cases of mild dry eye disease, especially if combined with the lifestyle changes outlined above.

In 2015, the most commonly prescribed artificial tear in England was hypromellose[14]

. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), more commonly known as hypromellose, is an inert, viscoelastic polymer. In The Pharmaceutical Journal’s survey, more than 70% of community pharmacists who responded said that they recommend hypromellose drops to patients very frequently, compared with more than 44% who said the same of carbomer. Hypromellose is cost effective and readily available both in preserved and non-preserved formulations, and is often indicated when ocular lubrication is required. However, to gain adequate relief, it may be necessary to administer this treatment very frequently (for example, hourly), so more viscous products are often required.

Carbomer 980, a viscoelastic lubricant, binds moisture to the ocular surface, increasing the time for which moisture is retained. This is particularly appropriate for overnight use or where extended protection is required during the day. Such carbomer-based gels tend to cause less blurring than ointments because the carbomer viscosity decreases on exposure to increased tear osmolarity, which is common in dry eye patients[15]

.

Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) is often seen as a second-line treatment option if hypromellose or carbomer 980 fails to give the desired relief[9]

. If severity is more advanced or if symptoms are chronic, it may be necessary to use a lubricant with viscosity increasing properties, such as sodium hyaluronate (SH). SH has a residency time on the ocular surface that is significantly higher than other artificial tears, such as hypromellose. Studies have shown SH to have greater symptomatic benefit than other formulations, including hypromellose[16],[17]

, carbomer[18],[19]

or CMC[20]

, particularly in more severe dry eye cases.

Hydroxypropyl guar (HP-guar) products increase in viscosity in contact with the ocular surface, forming a bio-adhesive gel. This in turn mimics the mucous layer of the tear film and increases aqueous retention. These products may be beneficial in mucous and aqueous deficiency, with specific product choice depending on severity[21],[22]

.

The proposed mechanism of action for lipid-containing artificial tear products involves stabilising the superficial lipid layer and subsequently reducing tear film evaporation. These products may be particularly useful in patients with evaporative dry eye disease, caused by either environmental conditions or secondary to MGD[23],[24]

. Furthermore, liposomal sprays have been shown to improve ocular comfort, increase the lipid layer thickness and promote tear film stability[25]

, particularly those containing soya lecithin, although some sprays worsen the condition[26]

.

Higher viscosity products are often required in severe dry eye or where increased residency time is required, for example, patients who cannot administer treatment on a regular basis because of physical difficulty, such as arthritis, or those with jobs that do not permit constant application of drops. Increased residency time is also beneficial for all patients, regardless of severity, for overnight wear because the corneal epithelium regenerates and added ocular lubrication is beneficial.

Paraffin, a high viscosity polymer, is the most common ointment, mixed with either wool fat, vitamin A, mineral oil or lanolin. Research suggests a superior long-lasting effect compared with aqueous based ocular lubricants[27]

, although these preparations can blur vision, irritate the eye and potentially delay wound healing[28]

.

Despite the variance in tear film supplements available, evidence is lacking in the superiority of particular treatments for subtypes of dry eye, making it difficult to apply an evidence-based approach when recommending specific products[29]

. However, specific treatments should depend on dry eye severity and aetiology[2]

. The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS), published as the DEWS report in 2007 (an updated version is due to be published in 2017), recommends a symptoms-based diagnosis and treatment plan with objective tests providing additional information[30]

. This highlights the important role of symptom assessment in the diagnosis of this disease.

Administration

Patients should be reminded that dry eye is a chronic condition, particularly where there are contributing or causative conditions such as blepharitis or MGD, so ongoing treatment is essential.

Many patients struggle with instillation, particularly older patients who may have arthritis. Therefore, an appropriate administration method and the ease of use of the recommended product should be considered. Some patients may prefer preparations that are squeezed from tubes or bottles, while others may find a larger “pump-action” multiuse bottle or spray is easier to use.

Furthermore, the pharmacist should provide advice about storage, how long a product can be used after first opening and how to reduce contamination by avoiding contact with the ocular surface and recapping the product. If products are used in conjunction with other eye drops or eye ointments, there should be an application time interval of approximately five minutes between uses. The most viscous products should be applied last. If the viscous preparations are used before other products — for example, if a patient uses a lubricant followed by an eye ointment before bed — the interval between treatments should be increased. This should be made clear to patients to ensure efficacy of the recommended treatment.

Dosage

It is vital to advise patients not only on how to use the prescribed treatment but also on the correct dosage. Many patients only apply drops when symptomatic. This sporadic use of treatment will provide temporary symptomatic relief but will not improve long-term ocular health. Although manufacturers’ instructions should usually be followed, four times daily dosage is generally considered necessary for symptomatic improvement[29]

. Ointments should be used overnight only, except in severe cases. If patients use these formulations during waking hours, they must be made aware of the potential side effects, including irritation and blurred vision.

Preservatives

To minimise the microbial load of products in use, many multipurpose preparations contain preservatives. However, most dry eye treatments require multiple administrations of topical therapies throughout the day and frequent use of preserved preparations can lead to worsening of the condition. This is because commonly used preservatives are surfactants that disrupt the tear film[9]

.

An additive often used in preparations with preservatives is disodium edetate (EDTA). Alone it is not a sufficient preservative; it is usually used to augment the preservative efficacy of benzalkonium chloride and other preservatives. Although it has shown efficacy in limiting microbial growth, reports propose EDTA may have a toxic effect on the ocular surface epithelium[31]

.

‘Vanishing’ preservatives, such as sodium perborate or sodium chlorite, although expensive to manufacture, allow the use of multiuse lubricants as opposed to unit dose and avoid preservative toxicity[9]

. However, the best option is to use preservative-free eye drops. Vanishing preservatives may be tolerated by some users but in patients with inadequate tear films these products are not usually well tolerated[9]

.

Managing blepharitis and MGD

The traditional treatment of blepharitis and MGD typically relies on improving eyelid hygiene with the use of diluted baby shampoo[32],[33]

. There is no consensus about the dilution factor, however, and there are concerns that this could result in an allergic response[34]

.

There are a wide variety of lid hygiene products available, including wipes, solutions and gels. Commercial lid cleaning products have demonstrated a significant improvement in eyelid margin tissue in subjects with blepharitis or MGD over a three-month period[35]

. Furthermore, a recent study reported a significantly increased benefit from using a commercial product compared with diluted baby shampoo[36]

. Patients have indicated a preference for commercial lid hygiene products compared with diluted home remedies on account of convenience and ease of use[37]

but increased cost implications must be considered.

MGD management should also include the use of a warm compress, such as a hot wet towel or eyelid warming mask, to improve gland function[11]

. However, eyelid temperature influences how effective this is[38]

and a hot flannel does not retain sufficient effective heat compared with commercial lid warming devices[39]

. Performing lid massage after a warm compress may be of further benefit; patients should be instructed to apply traction to the outer corner of the eyelid before applying gentle pressure with the other hand, working across the whole eyelid in an upward motion towards the lid margin[11]

.

Initially, patients should be advised to clean their eyelids twice daily. Once signs and symptoms start to improve, the frequency can be reduced but should be sufficiently regular to allow for effective management. Warm compresses are typically recommended for a ten-minute period, twice daily, although manufacturers’ recommendations for different lid warming devices may vary. Again, this may be reduced in frequency. However, the chronic nature of blepharitis and MGD should be carefully explained to the patient to ensure they understand the need for ongoing management.

Lid hygiene or warm compresses alone may not achieve significant improvement in moderate to severe cases. Combination therapies, such as the use of lid wipes, ocular lubricants and omega-3 supplements, have been shown to be effective in patients with MGD[40]

.

A meta-analysis of seven randomised controlled studies indicated that omega-3 supplementation improves tear film properties[41]

. Several formulations of omega-3 supplements, specifically for dry eye, are now commercially available, including Visonace (Vitabiotics) and PRN Omega Eye (Scope Healthcare). While the mechanism is not understood, improvements in patients with evaporative dry eye from MGD or contact lens wear have been observed following supplementation[42],[43]

.

Pharmaceutical management may also be indicated. If lid hygiene is ineffective, especially if there are signs of staphylococcal infection, then chloramphenicol eye ointment can be prescribed for application twice daily for six weeks, although it is not available over the counter for this indication[32]

. There is increasing evidence that low-dose oral tetracyclines are effective in MGD and blepharitis management[34],[44]

with good overall tolerance[11]

. Ciclosporin (cyclosporine), an anti-inflammatory treatment, is also being increasingly used to manage various forms of dry eye[11],

[45],[46],[47]

and has received approval in England and Wales from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for use in patients who are unresponsive to tear supplementation. It has also received approval in Scotland for the treatment of severe keratitis in adult patients with dry eye disease that has not improved despite treatment with tear substitutes.

Contact lens wearers

Dryness is a leading cause of discomfort in contact lens wearers[48]

. While occasional drying with contact lenses can be managed with appropriate topical lubricants often specifically marketed as “comfort-drops”, patients reporting regular discomfort should visit their optometrist. Changes to the contact lens material, replacement frequency (such as changing reusable lenses to daily disposables), contact lens solution or compliance, or addressing contributing factors, are often more effective than managing symptoms with lubricants alone[49]

.

Advice should be given to patients regarding contact lens wear. Many non-preserved products are contact lens compatible and can be used with contact lenses in situ. Others require waiting for a short period (normally 15 minutes) after application before contact lenses can be inserted.

Particular care should be taken with products containing preservatives. Preservatives are known to be absorbed by the matrix of soft contact lenses. Over time this can build up in contact lenses, causing irritation and discoloration. For this reason, many products are not licensed for use with contact lenses and this information should be relayed to the patient. Manufacturers’ guidance should be adhered to in this instance.

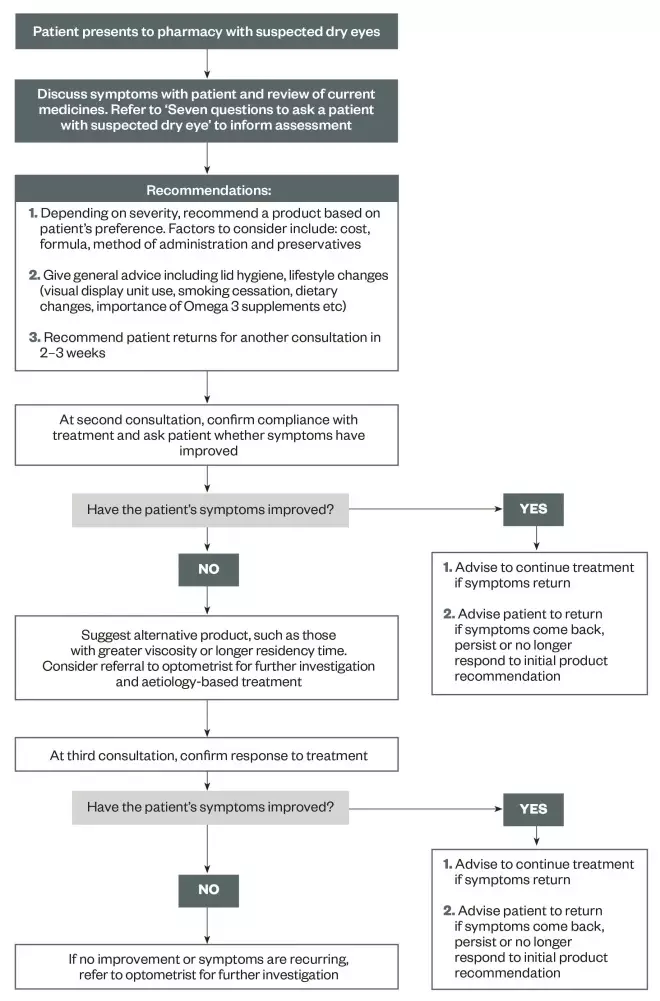

Referring patients

A management algorithm for patients presenting to community pharmacy with intermittent or mild symptoms of dry eye is shown in ‘Figure 1: Treatment algorithm for patients with dry eye’. The majority of dry eye conditions can be managed effectively in the community.

Assessment of symptoms alone cannot enable the pharmacist to make a differential diagnosis of aqueous deficiency or evaporative dry eye because they typically share characteristics[2]

. Therefore, patients presenting with symptoms of dry eye who do not respond to initial tear supplementation or with severe symptoms should be encouraged to visit their local optometrist for further investigation to allow the aetiology to be established. Evidence shows that optometrists can adequately tailor treatment to the severity of the dry eye[50]

so management is likely to be more effective with the involvement of an optometrist.

Optometrists who have undertaken additional training may offer supplementary NHS tests or partake in shared care initiatives (including Primary Eyecare Assessment and Referral Scheme [PEARS] or Minor Eye Conditions Service Pathway [MECS]) for patients reporting acute, specific eye complaints such as dry eye.

Analysis of the PEARS scheme indicated that the majority of patients were managed within optometric practice without further referral and a good availability of access[51]

. Furthermore, a small proportion of optometrists have gained an independent prescribing qualification, allowing them to prescribe licensed drugs where necessary, and some practices offer specialist dry eye clinics for a fee. The level of service can vary between different practices so pharmacists should engage with their local optometrists to discuss each other’s practice and the preferred route for referral.

Compliant patients with increasing symptoms, who do not respond to treatment after 4–6 weeks, should be considered for referral into secondary care[10]

.

Figure 1: Treatment algorithm for patients with dry eye

Suggested pathway for treating patients presenting to community pharmacy with intermittent or mild symptoms of dry eye.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Drugs and Therapeutics Bulletin. The management of dry eye. The BMJ 2016;353:i2333. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2333

[2] American Academy of Ophthalmology.Dry Eye Syndrome. Preferred Practice Pattern 2013. Available at: http://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/dry-eye-syndrome-ppp–2013 (accessed 28 May 2016)

[3] Wolffsohn J & Bilkhu P. Identification of dry eye conditions in community pharmacy. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2016. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20201138

[4] Nichols KK, Foulks GN, Bron AJ et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: executive summary. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52(4):1922–1929. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997a

[5] Baudouin C, Messmer EM, Aragona P et al. Revisiting the vicious circle of dry eye disease: a focus on the pathophysiology of meibomian gland dysfunction. Br J Ophthalmol 2016;100(3):300–306. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307415

[6] Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Prescribing Guidelines for Ocular Lubricants. Available at: http://www.moorfields.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/Prescribing%20Guidelines%20for%20Ocular%20Lubricants%202014.pdf (accessed 10 May 2016)

[7] Surrey, North East Hampshire & Farnham CCG, Crawley CCG and Horsham & Mid-Sussex CCG. Prescribing Guidelines for Dry Eye Management. Available at: http://www.surreyandsussex.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Surrey-PCN-Dry-Eyes-Management1.pdf (accessed 10 May 2016)

[8] Korb DR & Blackie CA. “Dry eye” is the wrong diagnosis for millions. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92(9):e350–354. doi: 10.1097/opx.0000000000000676

[9] Management and therapy of dry eye disease: report of the Management and Therapy Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop. Ocul Surf 2007;5(2):163–178. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70085-x

[10] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Dry Eye Syndrome. Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/dry-eye-syndrome#!scenario (accessed 9 May 2016)

[11] Geerling G, Tauber J, Baudouin C et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on management and treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52(4):2050–2064. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997g

[12] Asbell PA. Increasing importance of dry eye syndrome and the ideal artificial tear: consensus views from a roundtable discussion. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22(11):2149–2157. doi: 10.1185/030079906x132640

[13] Baudouin C, Aragona P, Van Setten G et al. Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: a clear and practical algorithm. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98(9):1168–1176. doi: bjophthalmol-2013-304619

[14] Health and Social Care information centre. Prescription cost analysis – 2015. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB20200/pres-cost-anal-eng-2015-rep.pdf (accessed 18 May 2016)

[15] Vehige JG & Simmons PA. Ocular lubrication vs. viscosity of ophthalmic products. Available at: http://www.clspectrum.com/articleviewer.aspx?articleID=12720 (accessed 18 May 2016)

[16] Prabhasawat P, Tesavibul N & Kasetsuwan N. Performance profile of sodium hyaluronate in patients with lipid tear deficiency: randomised, double-blind, controlled, exploratory study. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91(1):47–50 doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.097691

[17] Prabhasawat P, Ngamkae R, Nattaporn T et al. Effect of 0.3% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose/dextran versus 0.18% sodium hyaluronate in the treatment of ocular surface disease in glaucoma patients: a randomized, double-blind, and controlled study. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2015;31(6):323–329. doi: 10.1089/jop.2014.0115

[18] Baeyens V, Bron A & Baudouin C. Efficacy of 0.18% hypotonic sodium hyaluronate ophthalmic solution in the treatment of signs and symptoms of dry eye disease. J Fr Opthalmol 2012;35(6):412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2011.07.017

[19] Johnson ME, Murphy PJ & Boulton M. Carbomer and sodium hyaluronate eyedrops for moderate dry eye treatment. Optom Vis Sci 2008;85(8):750–757. doi: 10.1097/opx.0b013e318182476c

[20] Oh HJ, Li Z, Park S et al. Effect of hypotonic 0.18% sodium hyaluronate eyedrops on inflammation of the ocular surface in experimental dry eye. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2014;30(7):533–542. doi: 10.1089/jop.2013.0050

[21] Gifford P, Evans BJ & Morris J. A clinical evaluation of Systane. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2006;29(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2005.12.003

[22] Foulks GN. Clinical evaluation of the efficacy of PEG/PG lubricant eye drops with gelling agent (HP-Guar) for the relief of the signs and symptoms of dry eye disease: a review. Drugs Today (Barc) 2007;43(12):887–896. doi: 10.1358/dot.2007.43.12.1162080

[23] Kaercher T, Thelan U, Brief G et al. A prospective, multicenter, noninterventional study of Optive Plus((R)) in the treatment of patients with dry eye: the prolipid study. Clin Ophthalmol 2014;8:1147–1155. doi: 10.2147/opth.s58464

[24] Aguilar AJ, Marquez MI, Albera P et al. Effects of Systane((R)) Balance on noninvasive tear film break-up time in patients with lipid-deficient dry eye. Clin Ophthalmol 2014:8:2365–2372. doi: 10.2147/opth.s70623

[25] Craig JP, Purslow C, Murphy PJ et al. Effect of a liposomal spray on the pre-ocular tear film. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2010;33(2):83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.12.007

[26] Pult H, F Gill & Riede-Pult BH. Effect of three different liposomal eye sprays on ocular comfort and tear film. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2012;35(5):203–207;quiz 243–244. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2012.05.003

[27] Pilotaz F, Pecout A & Do M. Study of Xailin Night physical properties versus marketed ocular lubricant products. Acta Ophthalmologica 2015;93:((S225)). doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2015.0590

[28] Heerema JC & Friedenwald JS. Retardation of wound healing in the corneal epithelium by lanolin. Am J Ophthalmol 1950;33(9):1421–1427. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(50)91839-3

[29] Downie LE & Keller PR. A pragmatic approach to dry eye diagnosis: evidence into practice. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92(12):1189–1197. doi: 10.1097/opx.0000000000000721

[30] Methodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: report of the Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop. 2007. The Ocular Surface 2007;5(2):108–152. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70083-6

[31] Lopez Bernal D & Ubels JL. Quantitative evaluation of the corneal epithelial barrier: effect of artificial tears and preservatives. Curr Eye Res 1991;10(7):645–656. doi: 10.3109/02713689109013856

[32] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: blepharitis. Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/blepharitis#!scenario (accessed 27 May 2016)

[33] The College of Optometrists. Clinical management guidelines: blepharitis (Lid Margin Disease). Available at: http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/utilities/document-summary.cfm/docid/91502CC4-6126-47D9-A707F0E015D55230 (accessed 28 May 2016)

[34] Thode AR & Latkany RA. Current and emerging therapeutic strategies for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD). Drugs 2015;75(11):1177–1185. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0432-8

[35] Guillon M, Maissa C & Wong S. Symptomatic relief associated with eyelid hygiene in anterior blepharitis and MGD. Eye Contact Lens 2012;38(5):306–312. doi: 10.1097/icl.0b013e3182658699

[36] Khaireddin R & Hueber A. [Eyelid hygiene for contact lens wearers with blepharitis. Comparative investigation of treatment with baby shampoo versus phospholipid solution]. Ophthalmologe 2013;110(2):146–153. doi.org/10.1007/s00347-013-2804-3

[37] Key JE. A comparative study of eyelid cleaning regimens in chronic blepharitis. CLAO J 1996;22(3):209–212. PMID: 8828939

[38] Nagymihalyi AS, Dikstein S & Tiffany JM. The influence of eyelid temperature on the delivery of meibomian oil. Exp Eye Res 2004;78(3):367–370. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00197-0

[39] Bitton E, Lacroix Z & Leger S. In-vivo heat retention comparison of eyelid warming masks. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2016;39(4):311–315. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2016.04.002

[40] Korb DR, Blackie CA, Finnemore VM et al. Effect of using a combination of lid wipes, eye drops, and omega-3 supplements on meibomian gland functionality in patients with lipid deficient/evaporative dry eye. Cornea 2015;34(4):407–412. doi: 10.1097/ico.0000000000000366

[41] Liu A. & Ji J. Omega-3 essential fatty acids therapy for dry eye syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Med Sci Monit 2014:20:1583–1589. doi: 10.12659/msm.891364

[42] Macsai MS. The role of omega-3 dietary supplementation in blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction (an AOS thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2008;106:336–356. PMC: 2646454

[43] Bhargava R & Kumar P. Oral omega-3 fatty acid treatment for dry eye in contact lens wearers. Cornea 2015;34(4):413–420. doi: 10.1097/ico.0000000000000386

[44] Doughty MJ. On the prescribing of oral doxycycline or minocycline by UK optometrists as part of management of chronic Meibomian Gland Dysfunction (MGD). Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2016;39(1):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2015.08.002

[45] Ames P & Galor A. Cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsions for the treatment of dry eye: a review of the clinical evidence. Clin Investig (Lond) 2015;5(3):267–285. doi: 10.4155/cli.14.135

[46] Leonardi A, Van Setten G, Amrane M et al. Efficacy and safety of 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion in the treatment of severe dry eye disease: a multicenter randomized trial. Eur J Ophthalmol 2016;26(4):287–296. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000779

[47] Sy A, Kieran S, O’Brien MP et al. Expert opinion in the management of aqueous Deficient Dry Eye Disease (DED). BMC Ophthalmol 2015;15:133. doi: 10.1186/s12886-015-0122-z

[48] Nichols JJ, Willcox MD, Bron AJ et al. The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: executive summary. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54(11):Tfos7–13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13212

[49] Papas EB, Ciolino JB, Jacobs D et al. The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: report of the management and therapy subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54(11):Tfos183–203. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13166

[50] Downie LE, Rumney N, Gad A et al. Comparing self-reported optometric dry eye clinical practices in Australia and the United Kingdom: is there scope for practice improvement? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2016;36(2):140–151. doi: 10.1111/opo.12280

[51] Sheen NJ, Fone D, Phillips CJ et al. Novel optometrist-led all Wales primary eye-care services: evaluation of a prospective case series. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93(4):435–438. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.144329

You might also be interested in…

The importance of diverse clinical imagery within health education

Entrustable professional activities: a new approach to supervising trainee pharmacists on clinical placements