Shutterstock.com

There is a pervasive risk of dispensing errors in both community and hospital practice, owing to dispensing being a mentally and physically demanding activity that can be affected (either positively or negatively) by social, physical and technical features of the pharmacy[1]

. This knowledge has formed the basis of interventions to improve patient safety across different healthcare activities, ranging from interaction with devices or medical records to running a care pathway.

While the body of evidence to support such interventions is yet to be fully developed, the few evaluations that have been carried out, to date, suggest benefits for care processes (such as reduced error rates and increased efficiency), patient outcomes (such as increased confidence of patients to access medical information) and healthcare workers (such as increased job satisfaction)[2],[3]

.

Professional guidance from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society highlights that it is incumbent on pharmacies to report and learn from instances of dispensing errors and near misses, and to share and act on this learning[4]

. In addition, patient safety researchers have advocated the undertaking of prospective risk analyses to identify the potential for errors to happen in future – that is: to be “wise before the event”[5],[6]

. The insights gained from these analyses can inform not just local improvements, but also the design of larger-scale interventions.

This article builds upon the ideas proposed in ‘Understanding dispensing errors and risk’, and also proposes strategies and methods that should be considered for use in the pharmacy to manage the risk of dispensing errors.

Understanding safe practice

A good place to start is with the question: “How safe is your pharmacy’s practice?”. According to Vincent et al., that question could be broken down into the following more specific points:

- “Has your service been safe in the past?” — consider what harm has previously occurred to patients as a result of using the pharmacy’s services;

- “Are your systems and processes reliable?” — reflect on when and how often your work processes function as they should. For example, in catching potential dispensing errors and the frequency of near misses (e.g. daily, weekly, monthly);

- “Is your service safe today?” — consider what is done to ensure a clear understanding of day-to-day work and act on this knowledge. For example, having a regular safety ‘walk-round’ of the pharmacy, conducting regular discussions between staff members or eliciting the experiences of customers or patients;

- “Will your service be safe in the future?” — consider whether the team is prepared if something were to go wrong (e.g. a member of staff being absent). Do they know what the next steps should be? If not, consider what needs to be done to prepare them. For example, assessing the risk in practice or monitoring factors such as staffing and resources;

- “Are you responding and improving in the face of safety issues?” — if data are collected for safety issues, how well is this considered then acted upon? For example, using incident and near miss reports and complaints to change practice, feeding back audit data to staff. Consider if feedback is listened to and whether improvement has taken place[7]

.

Two methods that could help answer these questions for pharmacy are the failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) and the proactive risk monitoring (PRIMO) framework[8],[9]

.

Failure mode and effects analysis

Using FMEA involves identifying specific processes in practice – such as walk-in dispensing and monitored dosage system (MDS) dispensing – and rating potential ‘failure modes’ (i.e. instances of dispensing error in each process) in terms of their:

- Severity — how severe the potential outcome of the failure is;

- Frequency — how often the failure is likely to happen;

- Control measures — what is currently in place to prevent the failure from occurring or leading to harm if it does occur;

- Detectability — how likely the failure can be detected in time to mitigate any harm[8]

.

Severity and frequency are each rated on a scale of 1–4 and multiplied together to give an overall risk rating. This results in a number ranging from 1 to 16. The higher the rating, the higher the priority the failure has for risk reduction measures; ratings of 8 or more are typically classified as high risk. For each failure, existing control measures and detectability are brought in to assist with prioritisation, especially for failures with ratings of less than 8.

Example of a failure mode and effects analysis

This failure mode examines when the wrong medicine is dispensed to a patient in a hospital presurgical ward*.

Severity

The potential outcomes are:

- Lack of pain relief;

- Patient deterioration;

- Adverse reaction;

- Delay to the operation;

- Delay to discharge.

Therefore, severity has been rated as ‘moderate’ (2 on the scale of 1–4)

Frequency

It is not clear from incident reporting data how often this failure occurs because there appears to be some underreporting of incidents at the hospital. However, pharmacy staff are apparently often asked to resolve problems in the presurgical ward and the surgical teams often have to send items back to the pharmacy.

So, the frequency of the failure is rated as ‘frequent’ (4 on the scale of 1–4).

Detection

There is only one type of medication supplied to presurgical patients, which has a distinctive colour, shape and size, compared with other medication available from the dispensary. Therefore, the incorrect substitution of a different medication would be easy to detect.

Control measures

Instances of incorrect medication are typically detected by the ward supervisor or by the anaesthetist during the pre-operative ward visit. It is rare for the patient to have taken many doses of the incorrect medicine, if any at all, before an error is detected. This means that an existing control measure is in place.

Risk rating

The overall risk rating is calculated using severity x frequency, which gives a value of 8. Note that detectability is not used as part of the calculation; instead, it is used to make a qualitative judgement about the priority of failure modes that have a risk rating of lower than 8 (i.e. among failures with a low risk rating, those that are not easily detected are given priority for further examination, albeit after failure modes with a high risk rating, regardless of their detectability).

Using the information

When the same exercise was carried out for dispensing elsewhere in the hospital, it was appropriate to factor in detectability. It was found that:

- In the emergency department, the failure frequency was rated 2 and severity stayed the same (a score of 2), giving a risk rating of 4 (therefore a lower overall risk than in the presurgical ward). As in the presurgical ward, a failure was classed as ‘detectable’ owing to the distinctive medication used in the emergency department, as well as control measures in place — all medications are well organised and clearly labelled at the bedside, and are independently checked by an experienced member of staff before administration;

- In the oncology department, the failure frequency was rated 1, but severity was rated 4, also giving an overall risk rating of 4. Here, different medications look similar, meaning that a failure was regarded as ‘non-detectable’. However, as in the emergency department, all medications were organised well, labelled and checked, and so there were considered to be good control measures in place;

- In outpatient dispensing, as in the emergency department, the frequency and severity were both rated 2, resulting in an overall risk rating of 4. As in the oncology department, medication items were less distinctive in their appearance and so a failure here was also judged to be ‘non-detectable’. Control measures were judged to be poor as many patients use their medication at home without any further support.

In this example, the priority for addressing risk was judged to be dispensing in the presurgical ward, followed by outpatient dispensing, oncology dispensing and then emergency department dispensing. Discussion of the differences in ratings identified that, unlike in the surgery department, the other departments experience peak demand at a time when the pharmacy is able to devote all of its resources to dispensing. The pharmacy department proposes changing its shift pattern and rearranging its administrative tasks so that it has much of its resources available when demand peaks elsewhere. This has been projected to reduce failure frequency to a rating of 2 in the presurgical ward, without increasing the failure frequency elsewhere, as well as apparent negative consequences, and so will be considered for implementation. This leaves the problem of poor controls for outpatient dispensing, and so a future action is for the hospital to liaise with the community services to improve support for patients taking medication at home.

*Please note that this scenario is fictitious and the issues it refers to have been simplified for the purpose of illustrating how failure mode effects analysis works

In its original form, FMEA generates a risk score for each failure; this is then used to establish which failures are in most urgent need of preventative measures. In addition, the risk score would be used to assess the effect of any measure that is put in place to deal with a particular failure[8]

. There has, however, been recent caution against an overreliance on quantifying failure modes, owing to the poor reliability of the ratings; instead, the more useful learning seems to come from the discussions around severity, frequency and detectability that inform the ratings[10],[11]

.

Proactive risk monitoring

Another method — originally developed for use in pharmacies — is the PRIMO framework, which is designed to assess characteristics of a pharmacy that may either give rise to a dispensing error or help prevent one[9]

. Examples of these include:

- Staffing;

- Demand management;

- Training;

- Equipment;

- Team working;

- The physical work environment;

- Safety culture;

- Use of procedures;

- Job descriptions and task allocation;

- Communication[9]

.

Example of a proactive risk monitoring analysis

A community pharmacy has committed to carrying out a periodic review using the proactive risk monitoring (PRIMO) framework. To be able to collect the data needed for this review, the pharmacy staff:

- Reflect on problems that they encounter in the their day-to-day work;

- Examine incident and near miss reports;

- Rate the characteristics of their pharmacy using the PRIMO questionnaire[3]

.

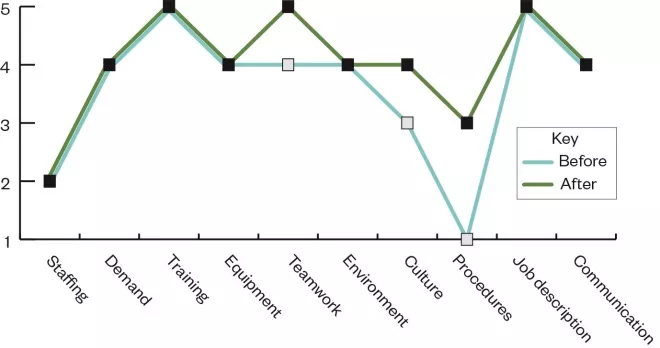

The first time they reviewed their pharmacy, they obtained the pattern of ratings shown in blue in the Figure.

Figure: Example proactive risk monitoring analysis framework before and after intervention

This profile suggests that there were some issues regarding staffing and the use of procedures. The staff’s reflection on their work highlighted that it was difficult to follow the set procedures at times when the pharmacy was understaffed. The pharmacy established an action plan to deal with these issues: they sought to improve their staffing provision and revised their standard operating procedures to make sure these were fit for purpose. The next time they carried out a review, the profile they obtained is shown in green in the Figure.

The purpose of the framework is to help identify issues that may need attention to reduce the chance of any incident occurring[9]

. While failure mode and effects analysis targets specific failures or errors, PRIMO targets specific features of the work setting; as such, these two approaches are complementary. Both are prospective assessments – that is, they ask “What could happen?” as opposed to incident investigation, which aims to ask “What did happen?” in the case of an actual incident[12]

.

Learning from safety incidents

Despite best efforts to prevent them, pharmacies will occasionally experience a dispensing error – with an estimated error rate of between 0.5% to 3%[13]

. When this happens, a responsive incident reporting and learning system will help draw insights about any underlying problems to allow them to be resolved[14]

. The system should be accessible to all members of staff, take a ‘just culture’ approach (considers whether there are problems with the work system that set staff up to fail rather than immediately assuming that staff are at fault) and should provide timely and useful information to the pharmacy team to help them make improvements[14]

.

For each incident that occurs, there will have been several near misses that could have become an incident[15]

. Learning from near misses is important too, as this will help expose the vulnerabilities that exist in the pharmacy’s processes (which then need to be addressed) and what safeguards are working (which should be maintained)[15]

. For example, asking why a medicines tray was completed incorrectly may lead to an understanding about the circumstances (e.g. location, staffing) under which an error is most likely to arise in such work, but also the circumstances under which such an error is most likely to be picked up.

No-harm incidents are as important for learning as those incidents that result in harm. If a no-harm incident occurs and is prevented from causing harm, this provides a learning opportunity. For example, if a carer recognises that the medicine is incorrect and queries it with the pharmacist prior to administration, this allows the pharmacy team to investigate why that issue occurred and put measures in place to prevent it from recurring. It is quite possible that, in the hands of a different individual, the incorrect medicine could have been taken.

Incidents and near misses can be attributed to a set of contributory factors. In broad terms, these relate to the:

- Patient;

- Task and equipment;

- Individual members of staff;

- Team;

- Work environment;

- Education and training;

- Organisational management[16],[17],[18]

.

Examples of each factor as they may relate to dispensing can be seen in Table 1[16],[17],[18]

. In theory, if a factor is implicated in an error, then an intervention or change will help to reduce the likelihood of the incident recurring. However, one factor may interact with another to produce particular instances of an error, and so the most obvious factor identified in an investigation may not be the only, or most important, one to be addressed.

The factors listed here are similar to those listed in the Yorkshire Contributory Factors Framework and those assessed in PRIMO[9],[19],[20]

. A link may be seen between the retrospective analysis of errors that have already occurred and the prospective analysis of situations in which a dispensing error could occur; both pointing to the action and interaction of work system characteristics in creating the circumstances for an error[21]

.

| Table 1: Dispensing errors contributory factors, examples and suggested prevention measures | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor | Examples | Prevention measure |

| The patient |

|

|

| Task and equipment |

|

|

| Individual members of staff |

|

|

| The team |

|

|

| The work environment |

|

|

| Education and training |

|

|

| Organisational management |

|

|

| Source: BMJ [16] , Taylor-Adams S[17] , Vincent C[18] | ||

In England and Wales, information can be sent to the National Reporting and Learning System or to NHS Controlled Drug Reporting to facilitate broader learning[22],[23]

. Pharmacies should have a medication safety officer who can advise on incident reporting and learning[12]

. If the pharmacy is part of a larger organisation or chain, it may have its own systems for collecting and sharing information about incidents.

Safety culture

Underlying a pharmacy’s approach to learning from dispensing errors, whether in anticipation of incidents or in response to them, is its safety culture. This refers to the manner in which a pharmacy deals with safety issues[24]

. More specifically, it describes:

- The values that are implicitly or explicitly communicated in the pharmacy (e.g. “It is worth investing in patient safety”; “We do not worry about an incident happening here”; “We must support our staff to work safely”)

- Patterns of behaviour that arise from these values, for example:

— How much training and equipment is provided;

— What staff are praised or reprimanded for;

— Engagement in incident reporting and learning[24]

.

Safety culture is reflected in how comfortable staff feel about discussing patient safety issues and how fairly they will be treated in the event of an incident[24],[25]

. NHS Improvement is currently promoting a ‘just culture’ approach, in which staff are treated in a constructive and fair way in relation to patient safety issues[25]

. Staff are only held accountable for their behaviour if they have been supported to practise safely by their work system[25]

.

Essential to achieving change in an organisation is engagement from all levels of the organisation. To assist with safety culture change, there are methods available to evaluate it and highlight areas to work on[24]

. Many of these methods are based on questionnaire surveys of pharmacy staff, such as the pharmacy safety climate questionnaire[26]

. An alternative approach is a structured group discussion that is guided by the Manchester patient safety framework[27],[28]

. This provides the group members with descriptions of safety culture that they can compare with their own experience, with the aim of stimulating discussion among the team about what may need to be changed to bring about improvement[29]

.

The ‘second victim’

This describes the pharmacy staff themselves who may be distressed, either by being involved in an incident (particularly if a patient is harmed), or by the consequences of having been involved, such as coming under scrutiny[30],[31]

. It is important that staff members involved in an incident are treated in a supportive and understanding manner – at the very least, non-judgemental listening, respite from the work and objective but sensitive feedback, with access to aftercare if necessary. A comprehensive support programme for ‘second victims’ may include:

- A safe space for reviewing what happened, with commitment to a just culture approach;

- Providing helpful and objective feedback about the incident, which informs broader education for staff members;

- Confidentiality and accessibility;

- Adaptive to the needs of the staff member(s) involved (e.g. basic peer support from colleagues through to in-depth support from pastoral or wellbeing services)[32],[33]

.

Involving patients

There is a question around to what extent patients should be involved in efforts to address safety problems. A recent review suggests that patients could make a valuable contribution to learning from specific incidents or to the prospective assessment of dispensing risks, but that there is not yet conclusive evidence on their involvement[34],[35]

. Including patients may provide an additional safeguard in medicines management processes, and being open and transparent in the case of a dispensing error may increase trust and the likelihood that the patient will cooperate with any investigation[36],[37],[38]

.

Given the current interest in exploring the potential contribution of patient involvement to safety improvement[39]

, and in the absence of firm guidance for pharmacies, pharmacy professionals should reflect and consider the following points in relation to their practice:

- How easy is it for the pharmacy and patients to communicate about medication safety issues? (e.g. Does the pharmacy encourage patients to speak up about concerns regarding their medicines?)

- How much trust exists between the pharmacy and its patients? (e.g. Can patients rely on the pharmacy to provide useful and accurate information about their medicines?)[40]

.

One way of gaining knowledge from patients may be through formal surveys, such as the community pharmacy patient questionnaire[41]

. However, pharmacies should also explore other avenues to involve patients, including through opportunistic conversations or in a more deliberate manner during incident investigations.

Summary

The relative infrequency of dispensing errors is a testament to the hard work of pharmacies in preventing their occurrence. However, there is still a risk of dispensing errors; even more so as pharmacies become busier during the COVID-19 pandemic. This article highlights what pharmacy teams can do to minimise the likelihood of errors and how to deal with them when they do occur. In managing the risk of dispensing errors, pharmacies should examine not just how their staff work, but also how the work of their staff is shaped by the circumstances under which it takes place.

About the authors

Denham Phipps is a lecturer, Ahmed Ashour is a doctoral student, Lisa Riste is a research fellow, Penny Lewis is a clinical lecturer, and Darren Ashcroft is a professor, all based in the School of Health Sciences and the National Institute for Health Research Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre, University of Manchester.

Useful resources

The authors have recently produced a learning package on patient safety for pharmacy staff in conjunction with the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. More details are available at: www.cppe.ac.uk/programmes/l/safety-e-01.

References

[1] Phipps D, Ashour A, Riste L et al. Understanding dispensing errors and risk. Pharm J 2020;305(7943):340–342. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2020.20208528

[2] Greenroyd FL, Hayward R, Price A et al. Using evidence-based design to improve pharmacy department efficiency. HERD 2016;10(1):130–143. doi: 10.1177/1937586716628276

[3] Xie A & Carayon P. A systematic review of human factors and ergonomics based healthcare system redesign for quality of care and patient safety. Ergonomics 2015;58(1):33–49. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2014.959070

[4] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Making things right when there has been a dispensing error. 2018. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/making-things-right (accessed December 2020)

[5] Potts HWW, Anderson JE, Colligan L et al. Assessing the validity of prospective hazards analysis methods: a comparison of two techniques. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-41

[6] Ward J, Clarkson J, Buckle P et al. Prospective hazards analysis: tailoring prospective methods to a healthcare context. Report to the Department of Health Patient Safety Research Programme, PS/035. Cambridge: University of Cambridge; 2010.

[7] Vincent C, Burnett S & Carthey J. The measurement and monitoring of patient safety. 2013. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/the-measurement-and-monitoring-of-safety (accessed December 2020)

[8] DeRosier J, Stalhandske E, Bagian JP et al. Using health care failure mode and effect analysis: the VA National Centre for Patient Safety’s prospective risk analysis system. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002 May;28(5):248–267, 209. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28025-6

[9] Sujan M A. A novel tool for organisational learning and its impact on safety culture in a hospital dispensary. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 2012;101:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2011.12.021

[10] Dean Franklin B, Shebl NA & Barber N. Failure mode and effects analysis: too little for too much? BMJ Qual Saf. 2012 Jul;21(7):607–611. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000723

[11] Ashley L & Armitage G. Failure mode and effects analysis: an empirical comparison of failure mode scoring procedures. J Patient Saf 2010;6(4):210–215. doi: 10.1097/pts.0b013e3181fc98d7

[12] Wake N. How to investigate and manage a medication incident. The Pharmaceutical Journal online. 2019. Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/cpd-and-learning/learning-article/how-to-investigate-and-manage-a-medication-incident/20206083.article?firstPass=false (accessed December 2020)

[13] James KL, Barlow D, McArtney R et al. Incidence, type and causes of dispensing errors: a review of the literature. Int J Pharm Pract 2009;17(1):9–30. PMID: 20218026

[14] NHS England & Improvement. Patient safety incident response framework 2020. 2020. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/patient-safety/incident-response-framework/ (accessed December 2020)

[15] McSweeney T & Moran DJ. Assessing and preventing serious incidents with behavioural science: enhancing Heinrich’s Triangle for the 21st century. J Organizational Behav Man 2017;37:283–300. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2017.1340923

[16] Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Chapman EJ et al. How to investigate and analyse clinical incidents: clinical risk unit and association of litigation and risk management protocol. BMJ 2000;320:777–781. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.777

[17] Taylor-Adams S & Vincent C. Systems analysis of clinical incidents: The London Protocol. 2016. Available at: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/patient-safety-translational-research-centre/education/training-materials-for-use-in-research-and-clinical-practice/the-london-protocol/ (accessed December 2020)

[18] Vincent C. Patient Safety, 2nd ed. Chichester: BMJ Books; 2010. ISBN:9781444323856

[19] Lawton R, McEachan RRC, Giles SJ et al. Development of an evidence-based framework of factors contributing to patient safety incidents in hospital settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21(5):369–380. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000443

[20] Garfield S & Dean Franklin B. Understanding models of error and how they apply in clinical practice. The Pharmaceutical Journal online. 2016. Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/cpd-and-learning/learning-article/understanding-models-of-error-and-how-they-apply-in-clinical-practice/20201110.article (accessed December 2020)

[21] Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ 2000;320:768 doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768

[22] The National Reporting and Learning System. NHS Improvement. 2020. Available at: https://report.nrls.nhs.uk/nrlsreporting/Default.aspx (accessed December 2020)

[23] Controlled drug reporting. NHS England. Available at: https://www.cdreporting.co.uk/ (accessed December 2020)

[24] Phipps D, Boyle T & Ashcroft D. Safety culture. In Tully M, Dean Franklin B (eds.). Safety in Medication Use. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2015. p.137-154

[25] NHS Improvement. A just culture guide. 2018. Available at: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/just-culture-guide/ (accessed December 2020)

[26] Phipps DL, De Bie J, Herborg H et al. Evaluation of the pharmacy safety climate questionnaire in European community pharmacies. International Journal of Quality in Health Care 2012;24(1):16–22. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr070

[27] National Patient Safety Agency. The Manchester Patient Safety Framework. 2006. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20171030124256/http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?EntryId45=59796 (accessed December 2020)

[28] Ashcroft DM, Morecroft C, Parker D & Noyce PR. Safety culture assessment in community pharmacy: development, face validity and feasibility of the Manchester Patient Safety Assessment Framework. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14(6):417–421. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.014332

[29] Phipps DL, Jones CEL, Parker D & Ashcroft DM. Organizational conditions for engagement in quality and safety improvement: a longitudinal qualitative study of community pharmacies. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):783. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3607-7

[30] Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR et al. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(5):325–330. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.032870

[31] Harrison R, Lawton R & Stewart K. Doctors’ experiences of adverse events in secondary care: the professional and personal impact. Clin Med (Lond). 2014;14(6):585–590. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-6-585

[32] Krzan KD, Merandi J, Morvay S et al. Implementation of a “second victim” programme in a pediatric hospital. American Journal of Health System Pharmacy 2015;72(1):563–567. doi: 10.1177/2516043518809457

[33] Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR et al. Caring for our own: deploying a system-wide second victim rapid response team. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2010;36(5):233–240. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36038-7

[34] Health Foundation. Involving patients in improving safety. 2013. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/InvolvingPatientsInImprovingSafety.pdf (accessed December 2020)

[35] Hall J, Peat M, Birks Y et al. Effectiveness of interventions designed to promote patient involvement to enhance safety: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19(5):e10. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.032748

[36] Garfield S, Jheeta S, Husson F et al. The role of hospital inpatients in supporting medication safety: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2016;11(4):e0153721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153721

[37] Fylan B, Armitage G, Naylor D & Blenkinsopp A. A qualitative study of patient involvement in medicines management after hospital discharge: an under-recognised source of system resilience. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27(7):539–546. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006813

[38] Bell SK, Smulowitz PB, Woodward AC et al. Disclosure, apology and offer programs: stakeholders’ views of barriers to and strategies for broad implementation. Milbank Q 2012;90(4):682–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00679.x

[39] O’Hara JK, Reynolds C, Moore S et al. What can patients tell us about the quality and safety of hospital care? Findings from a UK multicentre survey study. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27:673–682. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006974

[40] Phipps DL, Giles S, Lewis PJ et al. Mindful organizing in patients’ contributions to primary care medication safety. Health Expect 2018;21(6):964–972. doi: 10.1111/hex.12689

[41] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Community pharmacy patient questionnaire (CPPQ). 2020. Available at: https://psnc.org.uk/contract-it/essential-service-clinical-governance/cppq/ (accessed December 2020)