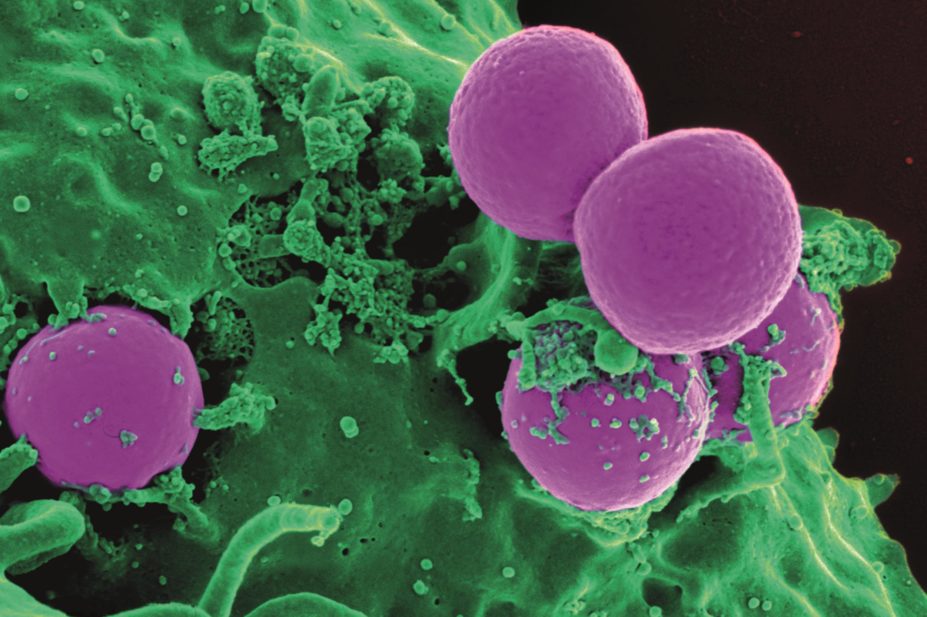

NIAID/NIH / Wikimedia Commons

Treatment with beta-lactam antibiotics could exacerbate methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) skin infections, according to pre-clinical research published in Cell Host & Microbe[1]

on 11 November 2015.

Scientists at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, used a mouse model to show that beta-lactams promote increased inflammation by inducing the resistance gene mecA.

“A poor choice of antibiotic can make MRSA infection worse compared with no treatment,” says Sabrina Muller, lead researcher on the project.

Beta-lactam antibiotics kill bacteria by inactivating penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which are involved in cell wall synthesis. PBPs help generate the bacterial cell wall polymer peptidoglycan (PGN), connecting glycan strands by a process called transpeptidation. However, the MRSA mecA gene confers resistance by coding for PBP2A, which has less affinity for beta-lactam antibiotics than the native PBPs that these antibiotics target.

Because MRSA survives, its PBP2A takes over the transpeptidation process. However, it produces a structurally different PGN, which — it was hypothesised — might induce an altered inflammatory response.

Using a mouse model, the researchers found that PBP2A induction in MRSA results in reduced PGN cross-linking, permitting enhanced degradation by phagocytes. This activates a component of the innate immune system, prompting the release of high concentrations of the cytokine interleukin (IL)-beta.

“MRSA exposed to beta-lactam antibiotics may have an increased deleterious effect on the host immune response to the infection when compared with that of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), or MRSA which has not been exposed to beta-lactams,” says John Coia, director of the Scottish Microbiology Reference Laboratories, who was not involved in the study. “This finding may partly explain the association of MRSA with greater morbidity and mortality than MSSA, and puts forward a biological mechanism for this observation.”

Alan Johnson, head of the department of healthcare-associated infection and antibiotic resistance at Public Health England (PHE), says the work is particularly relevant to the United States, where there have been significant problems with community-associated skin infections caused by MRSA.

The study authors say their research helps illuminate possible reasons to explain the difference in outcome between MRSA and MSSA infections. For example, between 30% and 80% of MRSA-infected individuals are thought to have been inappropriately treated, often with beta-lactam antibiotics, and studies have confirmed that “initial inappropriate antibiotic treatment is an independent predictive factor for mortality during MRSA bacteraemia”.

They further speculate that over-prescription of beta-lactam antibiotics such as ceftriaxone will continue due to lack of awareness, limited MRSA rapid diagnostic techniques and a reluctance not to over-prescribe the gold standard treatment for MRSA — vancomycin.

Coia says the investigators have made an interesting experimental observation worthy of further study, but that “it is unlikely to have immediate implications for the selection of empirical therapy for S aureus infections, particularly among those patients at low risk for MRSA infection”.

“Current empirical therapy for serious sepsis among patients known to be MRSA colonised, or at high risk of MRSA colonisation, should include an agent with activity against these organisms, for example a glycopeptide,” he says.

Johnson adds: “Fully understanding how pathogens such as MRSA cause infections helps us develop healthcare interventions to prevent them, for example, developing effective vaccines or new diagnostic tests.”

According to PHE[2]

, there were 801 cases of MRSA bacteraemia reported by NHS acute trusts in England between 1 April 2014 and 31 March 2015, a reduction of 7.1% in the number of cases compared with the previous year.

References

[1] Müller S, Wolf AJ, Iliev ID et al. Poorly cross-linked peptidoglycan in MRSA due to mecA induction activates the inflammasome and exacerbates immunopathology. Cell Host & Microbe 2015. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2015.10.011

[2] Public Health England. Annual Epidemiological Commentary: Mandatory MRSA, MSSA and E. coli bacteraemia and C. difficile infection data, 2014/15. 9 July 2015.