JL / Shutterstock.com

In the early hours of the morning on 12 April 2015, 21-year-old student Eloise Parry swallowed eight capsules of weight loss pill ‘DNP’. Less than 12 hours later, she was dead.

Parry was bulimic and had bought the 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) pills online from a website run by 31-year-old Bernard Rebelo.

Three years later, in a trial at Inner London Crown Court, it emerged that Rebelo, of Grimsby Grove, Beckton, east London, was importing the chemical in 24kg drums from China and repackaging it into capsules, making a profit of £200,000 per drum. Rebelo admitted selling Parry the pills but insisted he had never intended that they were for human consumption and said a warning on his website indicated this. Rebelo was convicted for two counts of manslaughter, although these have been subsequently overturned by the Court of Appeal on a technicality and he is likely to face a retrial.

Calls for tighter control

The case brought the dangers of DNP hurtling into public awareness. The compound is illegal to sell as a food or medical product, but can be sold legally as a fertiliser, wood preservative or dye, and even as a pesticide.

In January 2019, Victoria Atkins, parliamentary undersecretary of state for crime, safeguarding and vulnerability, wrote to the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) for its view on the appropriate control mechanism for DNP.

However, the ACMD concluded that, since there is no conclusive scientific evidence to indicate that DNP is psychoactive or that it is being misused with the intention of producing psychoactive effects, it would be inappropriate to control it under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. “We would suggest that the different policy teams involved across government work together with poisons experts to find a collective solution to DNP-related poisonings,” it said in a letter to Atkins.

Why is DNP available in any shape or form?

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) is among those calling for tighter controls on how the substance is sold. “Why is this available in any shape or form?” asks Ash Soni, president of the RPS. “It’s a fertiliser. I would’ve thought there’d be other things you could use in a fertiliser rather than DNP. Why can’t it just be banned?”

In March 2019, Soni, along with the Society’s chief scientist Gino Martini, wrote a letter to home secretary Sajid Javid urging the government to “immediately ban DNP to reduce the risk of harm, to commit to prosecuting those seeking to profit from it, and to encourage other countries to do the same”.

Despite heavy publicity around the toxicity of the drug in the past couple of years, the message that DNP is lethal does not seem to be getting through.

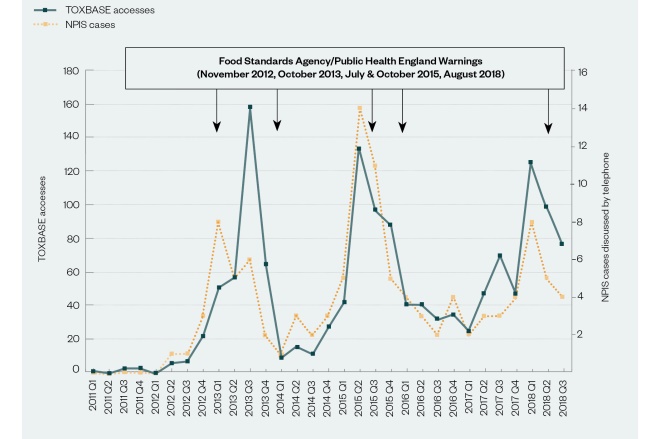

In fact, cases of DNP poisoning in the UK reported to the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) increased in 2018 following three years of steady decline. Latest statistics show that in the ten months between January 2018 and September 2018, there were 17 cases referred to the NPIS, compared with 12 in the whole of 2017. And 35% of these 17 cases proved fatal — the highest fatality rate seen in the past five years (see Table and Figure).

| Year | All systemic NPIS cases | Fatal cases | TOXBASE accesses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: National Poisons Information Service (NPIS). *Combined NPIS, Food Standards Agency and Office for National Statistics data | ||||||

| Males | Females | Total | NPIS data only | All data* | ||

| 2007 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | n/a |

| 2008 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| 2009 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 2010 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 2011 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 2012 | 5 | – | 5 | 1 | 2 | 35 |

| 2013 | 19 | 2 | 21 | 3 | 4 | 331 |

| 2014 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 63 |

| 2015 | 16 | 19 | 35 | 6 | 7 | 361 |

| 2016 | 7 | 6 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 149 |

| 2017 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 190 |

| 2018 (Jan-Sep) | 15 | 2 | 17 | 6 | 6 | 301 |

| Total | 74 | 41 | 115 | 20 | 26 | 1,460 |

Source: Reproduced with permission from the National Poisons Information Service

Figure: Quarterly numbers of NPIS cases referred by telephone and TOXBASE accesses relating to systemic 2,4-dinitrophenol exposure, 2011–2018

The number of cases of DNP poisoning discussed with the NPIS may seem small, compared with the thousands of cases relating to paracetamol poisoning, for example, but the high fatality risk associated with DNP as well as the uptick in cases are a cause for concern.

We only saw three cases of DNP poisoning in the five-year period 2007 to 2011, but since 2012 … we’ve now heard of around a total of 115 cases

“Until 2011, DNP was a very rare poison,” explains Simon Thomas, national clinical lead at the NPIS. “To put that in perspective, we only saw three cases of DNP poisoning in the five-year period 2007 to 2011, but since 2012 … we’ve now heard of around a total of 115 cases.”

Source: Simon Thomas

Simon Thomas, national clinical lead at the National Poisons Information Service, says the difference between the DNP dose required for weight loss and that associated with fatality is relatively small

These cases, of course, only paint part of the picture. By the time a case comes to the attention of the NPIS, a patient is likely displaying symptoms in an emergency room. The total number of people taking DNP in the UK is largely unknown.

What is clear, though, is that all healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, need to be aware of what DNP is and the risk it poses. “You would hope that a red flag is raised when [healthcare] professionals do hear about [DNP], and [they] know it’s potentially toxic,” says Thomas.

Introduction to the market

DNP was first used on an industrial scale to make bombs. Mixed with picric acid during the First World War to make explosives, its impact on workers in the French munitions factories acted as an early omen of how use would evolve. Those exposed felt fatigue, sweated excessively and had elevated body temperatures — and they also lost weight.

These symptoms occur because DNP works by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria. Energy is therefore released as heat, which means that adenosine triphosphate (ATP) — which provides energy for cell processes — is not made, explains Philip Strange, emeritus professor of pharmacology at the University of Reading.

“In principle, a little DNP might cause loss of body mass as the body breaks down fat to compensate for the lack of ATP.”

Observing this unintended weight loss among factory workers led to further studies and, by the early 1930s, it was being touted as a magic bullet for weight loss. According to Strange, by 1934, around 20 wholesale drug firms were marketing DNP and as many as 100,000 people had taken it in the United States alone. At this point the substance was still legal, so most sales occurred through local pharmacies.

If you get the dose wrong then breakdown of body fat coupled with overheating and a lack of ATP can lead to death. There is no effective treatment for someone who has taken too much

However, it quickly became apparent that DNP was less a magic bullet and more a deadly one. “It is very difficult to get the dose right,” Strange continues. “If you get the dose wrong then breakdown of body fat coupled with overheating and a lack of ATP can lead to death. There is no effective treatment for someone who has taken too much.”

As a result, side effects were common and severe and, in some cases, fatal. Finally, in the late 1930s, DNP was banned for sale as a diet pill in the United States (though it took until 2003 for the UK to do the same under General Food Laws).

Market expansion

Illegality was not enough to prevent further experimentation. Most significantly, physician Nicholas Bachynsky established clinics in the United States in the 1980s offering weight loss underpinned by the drug[1]

. It is alleged that 14,000 patients enrolled, but complaints about Bachynsky’s treatment accumulated leading to a US Food and Drug Administration investigation that resulted in his conviction for drug law violations. In 1986, an injunction was issued, prohibiting Bachynsky from dispensing DNP to any patients.

During the 1990s, DNP became increasingly popular among the bodybuilding community and, decades on, bodybuilders remain among the most likely to take the drug. It takes only a quick search to bring up multiple chats in online forums among those using DNP to shed fat and sculpt muscle. Many share progress shots as well as kilograms lost and the amount of the drugs they consume, known as ‘cycles’. Others recommend how first-time users can start with small ‘runs’.

But while males continue to make up the majority of users, there is also an increasing proportion of women turning to the drug as a diet aid. “Due to the rise of social media, there is increased exposure to body shame and ‘thinspiration’,” says Chloe Adams, policy officer at the British Dietetic Association. “Being subject to airbrushed images of perceived ‘perfection’, idolisation of celebrity role models, and frequent use of social media is likely to enhance a young female preoccupation with image,” she explains.

DNP is often marketed with sensationalised claims, which can install hope in those who are emotionally vulnerable seeking a quick and easy fix

“DNP and other supplements are often marketed with sensationalised claims surrounding fat burn and rapid weight loss,” she adds. “This can install hope in those who are emotionally vulnerable seeking a quick and easy fix.”

Source: Chloe Adams

Chloe Adams, policy officer at the British Dietetic Association, says that DNP is now widely available to purchase from the internet through websites which appear to be legitimate

This widening of the potential demographic for DNP is particularly worrying, says Thomas. “That increasing use by females is concerning because the potential market for DNP as a weight loss aid among women is much larger than that for male bodybuilders. It could encourage DNP use at a much larger scale than we’ve seen before.”

This large-scale use could be lethal; of 115 cases referred to the NPIS since 2007, 17% have proved fatal. Though acute overdoses are the most lethal means of consumption, Thomas makes it clear there is no safe level of DNP, because the margins are so small.

“The difference in dose between that required for the weight loss people are looking for and the dose associated with fatality is relatively small,” he says. “It’s one of the reasons the substance is so dangerous and wholly unsuitable for any sort of human use, for any therapeutic or quasi-therapeutic purpose.”

Campaigns and tighter control

Despite the obvious dangers, convincing men and women of the risks of DNP is proving difficult — building awareness doesn’t seem enough to deter people from taking it. One young female user on Reddit describes taking up to 500mg daily for seven days, and losing six pounds. “If you know what you’re doing and are reasonable about what to expect,” she writes, then “DNP is an extremely powerful fat loss drug — its muscle sparing properties are unlike anything else”.

There are enough individuals who are willing to risk unpleasant side effects and potential harm to achieve their idea of bodily perfection that the messages don’t reach them

Ian Musgrave, senior lecturer in pharmacology at the University of Adelaide, Australia, agrees that the situation is challenging. “[There are] enough individuals who are willing to risk unpleasant side effects and potential harm to achieve their idea of bodily perfection that the messages don’t reach them,” he says.

Source: Ian Musgrave

Ian Musgrave, senior lecturer in pharmacology at the University of Adelaide, says that campaigns to raise awareness of the risks associated with taking DNP must be ongoing

Nevertheless, the Food Standards Agency (FSA), under whose remit DNP falls, says it is persevering with its campaign to raise awareness of the risks associated with taking DNP. “The dangers of DNP have been re-emphasised by Public Health England, and the FSA website holds clear information around the dangers,” a spokesperson says.

“The FSA has been vocal on the dangers of DNP in the past, particularly with the #DNPkills social media campaign, which was launched in 2015.”

These campaigns must be ongoing, advises Musgrave. “Public health messaging is a complex area, with variable success, targeting the at-risk communities, not talking down to them, regularly reinforcing the message and changing the campaigns so people are not desensitised.

“The bodybuilding and body sculpting communities will present unique challenges”, he adds.

Adams agrees. “Medical and professional bodies should be campaigning to advocate the dangers associated with the use of DNP through channels specifically targeting at-risk population groups, such as young adults via social media,” she says. “Body-positive role messages and models in the media would also be beneficial to target such audiences.”

As well as raising awareness, some — including the RPS — have called for tighter controls around the sale of DNP.

As was the case with Parry, users can quite easily buy the drug online. “DNP is now widely available to purchase from the internet through websites which appear to be legitimate,” says Adams. “It can be purchased easily from eBay and Amazon with a simple Google search. And websites with apparent testimonials also make the purchase of DNP seem to be desirable and safe.”

Soni says the RPS has a responsibility to keep putting pressure on the Home Office to ban any sales of the drug. “This is a poison at the end of the day,” he says. “If you go back to the origins of the RPS, it was formed as the gatekeeper to poisons, so it fits with our history and our responsibility to raise public awareness and to try to get it reclassified, or banned if we can.”

The FSA’s National Food Crime Unit (NFCU) says it already proactively targets those suspected to be selling DNP to UK consumers for consumption. “The unit constantly monitors the internet to identify websites that are marketing DNP for human consumption, and the people behind them,” a spokesperson says. “Where such people are traced to a UK address, we work with partners to execute search warrants, remove product and prosecute those involved.”

The spokesperson adds that the FSA is clear that DNP presents a serious risk to consumers when marketed for consumption. “This is why the NFCU works hard to limit the availability of DNP, working with partners in the UK and internationally to achieve this. The NFCU continually reviews its approach to this issue, to ensure it is as effective as it can be.”

Some direct-selling platforms are addressing the issue too. The RPS gives the example of eBay as one online marketplace that has been actively removing sellers. Not only does this limit availability, says an RPS spokesperson, but it removes the “apparent credibility that these sites provide”.

With the internet — especially non-UK sites — and with Chinese and Indian labs producing all kinds of chemicals, it is very difficult to shut off availability completely

“It looks as though the FSA has been pursuing suppliers of DNP aggressively,” agrees Strange. “This must have some effect in discouraging suppliers but, with the internet — especially non-UK sites — and with Chinese and Indian labs producing all kinds of chemicals, it is very difficult to shut off availability completely.”

Source: Philip Strange

Philip Strange, emeritus professor of pharmacology at the University of Reading, says it is very difficult to shut off availability of DNP completely

A quick look online, “and it seemed as though I could have bought the substance myself through the internet”, Strange says. He is right: in just two minutes online, you can find a bodybuilding site selling 100 capsules of DNP for around £130 and recommending a DNP cycle that includes appetite suppressants and a very low-carbohydrate diet as a catalyst to weight loss.

“Ultimately, a change in culture and society is required, and this will take years,” says Adams. “To drive this change, a multi-level approach must be taken to educate the population and put pressure on sellers of dangerous weight loss aids.”

Pharmacists’ role

The multi-level approach required includes a role to be played by pharmacists. Primarily, pharmacists need the awareness and knowledge to spot symptoms of DNP poisoning when a patient mentions they have taken it (see Box).

Box: Symptoms and management of 2,4-dinitrophenol toxicity

Symptoms of acute 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) poisoning include fever, dehydration, nausea, vomiting, restlessness, flushed skin and a rapid heartbeat. These can quickly progress to coma and death. Even after prolonged and seemingly uneventful use, this toxicity can develop, says the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS), and anyone with symptoms needs to be referred straight to hospital for treatment.

According to guidelines on TOXBASE, the clinical toxicology database of the NPIS available to NHS healthcare professionals, those handling emergency cases are advised to quickly introduce cooling measures, fluid resuscitation and sedation to increase the likelihood of recovery.

Additional guidance includes ensuring that the patient has a clear airway, and regularly monitoring temperature, pulse and blood pressure. Agitation can be treated with sedation and patients should be observed for at least 12 hours after consuming the drug.

“Managing DNP poisoning in emergency departments can be very challenging,” says the NPIS. “This is an uncommon form of poisoning and healthcare professionals are unlikely to have experience of it.

“There is no specific antidote and patients commonly deteriorate rapidly. Management guidance is available on TOXBASE and this has advised that all cases should be discussed directly with the NPIS because of the high risk of fatality.”

For long-term users, symptoms may include cataracts and skin lesions.

Resources are available for any pharmacist looking to find out more about DNP, says Thomas. “If you, as a pharmacist, can plug DNP into TOXBASE [the clinical toxicology database of the NPIS available to NHS healthcare professionals], it will give you very clear warnings about the toxicity of that straightaway.”

The FSA adds that it asks pharmacists to be vigilant for sales of DNP via marketplace websites. “If you have information to share with the National Food Crime Unit around the sale of DNP, please call the Food Crime Confidential hotline on 020 7276 8787 or visit www.food.gov.uk/contact.”

Weight loss services should be promoted in every pharmacy, just as smoking cessation should be, and it should be an NHS service

More broadly, suggests Sudhir Sehrawat, a member of the RPS Welsh Pharmacy Board, pharmacies could, and should, offer a safe space where patients can come and discuss how to lose weight. “Personally, I think weight-loss services should be promoted in every pharmacy, just as smoking cessation should be, and it should be an NHS service,” he says.

Source: Sudhir Sehrawat

Sudhir Sehrawat, a member of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society Welsh Pharmacy Board, says that pharmacies could, and should, offer a safe space where patients can come and discuss how to lose weight

“I would really push the Department of Health and Social Care and the Welsh Assembly that these should be standard pharmacy services, all part of the healthy wellbeing of the population,” he suggests. “If they were then people would be less inclined to find something on the internet.”

That sentiment is echoed by Soni. “Encouraging people to recognise the need to speak to their healthcare professional, seek professional advice and have that conversation with people, it’s an important part of what we do,” he says.

“The challenge we face is doing it in a way which is not paternalistic, which encourages people to feel there’s nothing wrong with seeking advice and that it’s OK to go and ask those questions.”

“You’ve got to ask yourself, why did Eloise feel the need to search the internet to lose weight?” adds Sehrawat. “Why did she not feel [she could go] to see a healthcare professional?

“Yes, the internet is accessible to anyone, on any smart device. But pharmacies are accessible too. We’ve got to stop people thinking the internet is the first port of call.”

By doing so, lives could be saved.

References

[1] Grundlingh J, Dargan PI, El-Zanfaly M & Wood DM. 2,4-Dinitrophenol (DNP): A weight loss agent with significant acute toxicity and risk of death. J Med Toxicol 2011;7(3):205–212. doi: 10.1007/s13181-011-0162-6