Mclean/Shutterstock.com

As soon as Gilead Sciences announced that the antiviral remdesivir (Veklury) had shown efficacy in treating COVID-19, the race was on to get the investigational new drug to patients[1]

.

In the UK, this was achieved by way of the early access to medicines scheme (EAMS), which was developed to give patients with untreatable, life-threatening or seriously debilitating conditions access to medicines that have not yet received a marketing authorisation — and, in turn, hope.

“We have worked very hard to ensure that any medicines that are coming through the pipeline in the pandemic can reach patients as soon as possible,” says Daniel O’Connor, expert medical assessor at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), who manages EAMS.

On 26 May 2020, after an initial submission on 22 April 2020 and following a rolling review of clinical data submitted from mid-May 2020, remdesivir became the first COVID-19 treatment to receive a ‘positive scientific opinion’ under EAMS, allowing for its use in patients with COVID-19.

The EAMS status continued until 3 July 2020, when it received a conditional marketing authorisation from the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Pre-approval access is nothing new. In many instances, there has been ad-hoc compassionate use of unlicensed drugs, such as the successful new hepatitis C drug combination — ledipasvir and sofosbuvir — approved in 2014. But EAMS was developed to provide a more robust programme to support access.

The scheme was introduced in April 2014 to bridge the long, often agonising, gap between positive clinical trials and marketing authorisation. EAMS was welcomed by patient organisations and enthusiastically taken up by the pharmaceutical industry, which saw it as a valuable opportunity for early dialogue with government and arm’s length bodies about product uptake within the NHS.

It may be that the EAMS alone is not enough to truly improve medicines access for the patients that are most in need

However, uncertainty has grown as to whether the scheme is making progress on what it set out to achieve.

An independent review carried out in 2016 found that out of 17 companies asked, 10 reported that the EAMS was not currently delivering an attractive proposition for industry and 9 said that that the scheme had not been successful in delivering early patient access[2]

.

Jayne Spink, chief executive of Genetic Alliance UK, a national umbrella organisation that supports more than 200 rare disease charities, has previously said that EAMS has been a disappointment for patients with rare diseases: the very population who should be benefitting from it.

It may be that the EAMS alone is not enough to truly improve medicines access for the patients that are most in need.

How EAMS works

The two-step process developed by the MHRA starts with a company applying for a promising innovative medicine (PIM) designation, based on available clinical and non-clinical data to assess the benefit-risk balance.

“We commit to conducting a PIM designation meeting within four weeks of receipt of that application,” explains O’Connor. After the meeting, the designation is granted within four weeks, giving an early indication that a product is suitable for the second step — a positive scientific opinion — which then leads to patient access.

Progressing from an application to a positive scientific opinion usually takes around 75 days. Once the EAMS approval is granted, physicians can request the medicine, which is supplied for free by the company. For a positive scientific opinion, the benefits need to be shown to outweigh the risks, and this includes a safety assessment (see Box). The principles of the safety criteria are similar to those required for a marketing authorisation but include rigorous pharmacovigilance and risk management.

Box: Evidence for efficacy

With any early access scheme, there is a danger that access could be granted without real evidence of efficacy — an issue that was recently highlighted by the US Food and Drug Administration’s emergency use authorisation (EUA) for convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19. As with EAMS, the EUA scheme is able to provide access to treatments before they have received full authorisation.

The approval was backed only by data from an observational study, which the World Health Organization labelled as being of “very low quality”.

Doctors from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine voiced concerns that the early access and accompanying publicity will stimulate patient demand, making it more difficult to enrol patients into ongoing trials, where some patients receive only a placebo. They argue that this will make it more difficult to ascertain if the treatment shows efficacy.

Even with the most efficient system, there still needs to be processes in place to ensure that early access is appropriate.

“I’m a mum who looks after a son, who is wasting away in front of my eyes, and I think, the earlier we can get a treatment, the better,” says Alex Johnson, co-founder and joint chief executive of Duchenne UK. “But I am also a mum who is data driven.

“We need to see that the drugs are working [and] we need to see that there is a safety profile there.”

The EAMS approval lasts until marketing authorisation is received, but for patients already receiving the medicine, companies are required to ensure access continues until reimbursement is secured via the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), or an equivalent body.

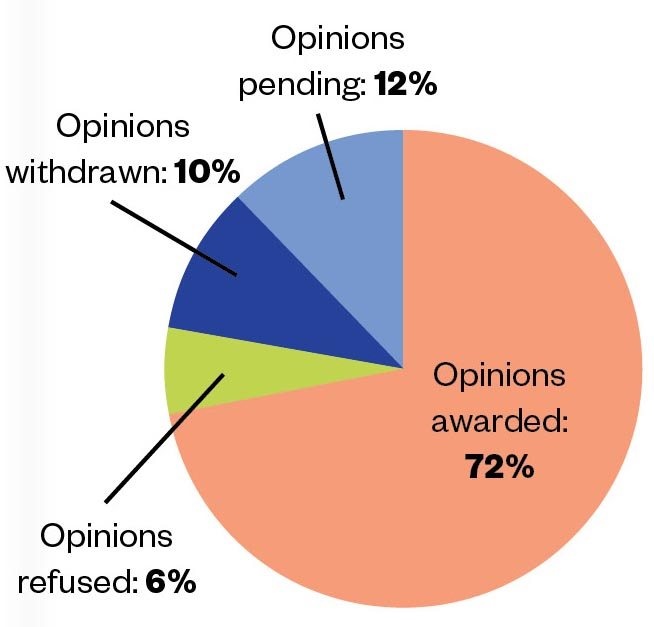

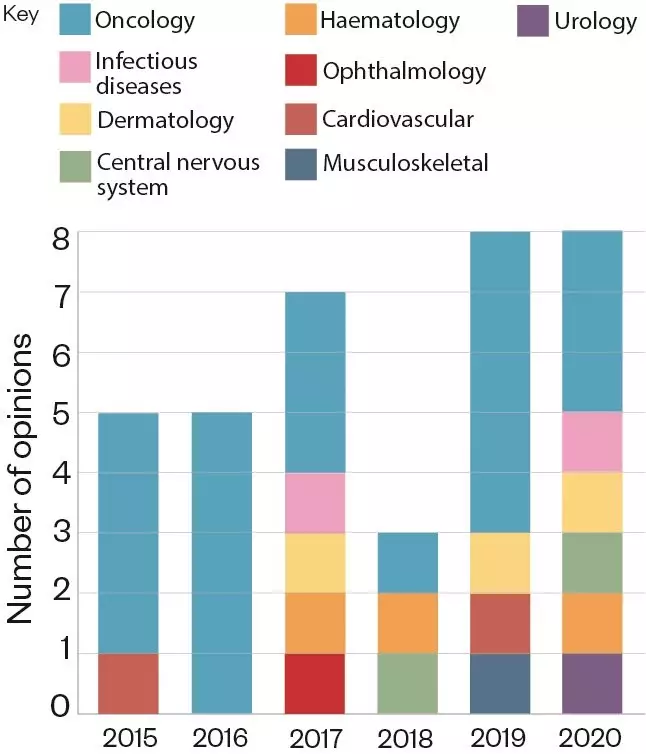

Since 2014, and as of 12 November 2020, the MHRA has issued 88 PIM designations and 36 positive scientific opinions for the benefit of more than 1,400 patients (see Figure 1)[3]

. According to O’Connor, the largest proportion of these was for cancer drugs but, increasingly, they are being issued for drugs to treat other areas of unmet medical need (see Figure 2).

Source: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

Figure 1: Between April 2014 and November 2020, 50 EAMS scientific opinion applications were made. Of these, 36 were awarded, 3 were refused, 5 were withdrawn and 6 are pending.

Source: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

Figure 2: Number of positive EAMS scientific opinions awarded in each therapeutic area, per year, since 2015.

He estimates that around 75% of PIM applications are granted and 60%–70% of applications for scientific opinions are positive.

Paul Catchpole, value and access director at the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), who was involved in the scheme’s inception, says he is slightly disappointed by the numbers: “Let’s say it’s 1,500 over six years, that’s only about 250 patients a year … I always thought, when we designed it, we’d be putting a lot more patients through … that just didn’t seem very many.”

One of the issues with the scheme is the length of time that the drug can be provided to patients within the programme

Perhaps it’s not a surprise that the list of companies that have embarked on the EAMS process is dominated by big pharma. Roche’s latest EAMS application was submitted in May 2020 for risdiplam (Evrysdi) — the first oral medicine for spinal muscular atrophy, a genetic disease affecting the nervous system. Since 2017, the company has run eight EAMS programmes. There were initially internal debates and resource concerns around the company’s participation, but Gregory Thomas, UK medical programmes leader at Roche, says it was concluded that “if [Roche] can establish early access with an EAMS, we should go for it”.

However, others have been critical of the scheme. At a 2018 meeting hosted by The House parliamentary magazine, Jasmin Hussein, head of dermatology at Sanofi, reported that the EAMS process could be a logistical nightmare. This was based on the company’s experience with dupilumab, an immunosuppressive drug for children with severe atopic dermatitis, which was awarded a PIM in 2015 but did not get a positive scientific opinion until August 2020.

One of the issues with the scheme is the length of time that the drug can be provided to patients within the programme. The MHRA had hoped that drugs could be made available for 12 to 18 months, the timescale it takes to apply for an EMA marketing authorisation; however, in practice, this is not the case.

“You need quite a robust dossier to submit to the MHRA; you need a lot of data which you are using for the EMA filing as well,” says Thomas. The longest EAMS Roche has run was seven months.

Widening participation

This issue, among others, may explain why uptake has been low with smaller drug companies.

“[They] have a smaller number of resources and, therefore, it might be particularly challenging for them to allocate [the task to] their internal regulatory and clinical trials [staff] who are preparing the main global regulation dossiers,” says Catchpole. But O’Connor says in the past few years he has started to see an increasing number of smaller companies apply for PIM designations.

One way to encourage participation could be to support companies in collecting pre-approval data from patients taking the drugs in real-world settings. This would help validate clinical trial findings and could assist companies in making their case for patient benefit in post-approval health technology assessments.

“It’s something that we are actively looking at,” says O’Connor, but it relies on the drug being available for a long enough period of time[4]

. “At the minute [the positive scientific opinion] tends to be quite close to the licensing point,” explains Catchpole.

However, early access to medicines continues to be on the agenda of many patient groups.

“We were very passionately involved in campaigning for the scheme,” says Alex Johnson, co-founder and joint chief executive of Duchenne UK, who found herself and her son Jack on the front pages of newspapers during their EAMS campaign. Jack was diagnosed with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), an incurable degenerative muscle-wasting condition, in 2011.

Between June 2017 and October 2020, idebenone (Raxone; Santhera Pharmaceuticals) was made available via EAMS for DMD patients who were showing a decline in respiratory function and not taking steroids[5]

. “We were obviously delighted to see that the company made this decision to give patients early access,” says Johnson.

Idebenone was turned down by the EMA in 2017 because of insufficient evidence of efficacy from its 66-patient clinical trial; however, in consultation with patient groups, the MHRA renewed its positive scientific opinion while further trials were ongoing.

But, in October 2020, Santhera made the decision to discontinue the idebenone EAMS programme and to stop all existing and further clinical development of the drug in DMD. This followed interim analysis of a phase III, randomised controlled trial, called SIDEROS, which suggested that idebenone did not slow the decline of participants’ respiratory function.

“An EAMS scientific opinion can only remain in place if there is some prospect of a licence for a medicine being granted, and that is no longer the case for idebenone,” a spokesperson for the MHRA told The Pharmaceutical Journal.

Idebenone will continue to be made available for periods of up to three months to UK patients who are currently receiving the medicine through EAMS, following discussions with their clinician.

We know of patients who felt idebenone was improving their respiratory function, and now feel breathless since the trial has stopped and are worried about dying.

Emily Crossley, who is co-founder and joint chief executive of Duchenne UK with Johnson, says the charity was “disappointed” to see the early termination of the SIDEROS trial, and the end of access to idebenone through the EAMS.

“It is worth noting that the failed clinical trial had a steroid-using patient population, while those receiving idebenone under EAMS are non-steroid users — a population which has seen a benefit from idebenone in previous studies.

“The shocking withdrawal of a promising treatment can be devastating to families and patients, and can be hard news to come to terms with,” she adds. “We know of patients who felt idebenone was improving their respiratory function, and now feel breathless since the trial has stopped and are worried about dying.”

A band-aid on a bullet wound

The issue of who pays for the drug during EAMS is a factor that may be holding back participation.

And Johnson says the situation is likely to worsen as new expensive cell and gene therapies are developed. “I struggle to see how, under the current scheme, [cell and gene therapies] could be provided through EAMS.”

Catchpole and the ABPI are asking for commercial recognition of the value of EAMS stock. “We’re not saying [the NHS should] pay for all of the EAMS medicines — that would be not appropriate,” he says; but in any subsequent commercial access agreement, they would like to see the value of stock already provided being taken into consideration.

Another problem holding back patient access is getting information to physicians, since many NHS staff are unaware of the scheme. Pharmaceutical companies are not able to communicate before marketing approval is granted, so this is down to the MHRA. However, communication is improving, afccording to O’Connor: “Now, after we give the PIM designation, we share [it] in confidence to other stakeholders.”

EAMS is not the be-all and end-all of freeing up access for patients

Six years after the EAMS scheme was introduced, Thomas believes there is some room for fine tuning, and a government-industry stakeholder task group is currently developing EAMS procedures.

Spink says, though, that while the scheme is part of the solution, “[EAMS] is not the be-all and end-all of freeing up access for patients”.

In 2019, Genetic Alliance UK published a report about the issues that slow down access to treatments for rare diseases — one of them being the small patient populations in clinical trials[6]

. This injects large degrees of uncertainty into proving the value of new drugs to agencies such as NICE.

There is also a problem with the fragmentation of the regulatory system, particularly at the health technology assessment stage. “Excluding EAMS, we counted 15 different mechanisms across the UK for evaluating a rare disease medicine, which is somewhat shocking when you consider that it might just be [for] a handful of [patients] within the UK,” says Spink.

Catchpole agrees, pointing out there is a “black hole” in the system where, after a marketing authorisation is granted, the EAMS designation immediately stops. This can lead to a three- or four-month gap where no further patients can gain access to the drug until its cost-effectiveness is assessed by NICE and reimbursement agreed with the NHS. “You’ve got to have good connectivity between all of those stages,” he says.

Schemes such as EAMS are important but, for Spink, they represent a small tweak of a system that requires much more fundamental change.

“It should be about examining the [whole] path from research to clinical care and removing hard boundaries to ensure, particularly where there’s unmet need and where conditions are progressive, that there aren’t any unnecessary barriers to people being able to access treatments.”

EAMS may have worked well in the case of remdesivir, but with so many patients missing out on other treatments, it is only a matter of time before a more fundamental overhaul is needed.

References

[1] Goldman J, Lye D, Hui D, et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 days in patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med online. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015301

[2] Accelerated Access Review. 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-early-access-to-medicines-scheme-eams (accessed November 2020)

[3] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2015. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/early-access-to-medicines-scheme-eams-scientific-opinions (accessed November 2020)

[4] Pang H, Wang M, Kiff C et al. Early Access to Medicines Scheme: real-world data collection. Drug Discovery Today 2019;24(12):2231-2233. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.06.009

[5] Buyse G, Voit T, Schara U, et al. Efficacy of idebenone on respiratory function in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy not using glucocorticoids (DELOS): a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2015;385(9979):1748–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60025-3

[6] Genetic Alliance. Action Access: A report from Genetic Alliance UK for the All Party Parliamentary Group on Rare, Genetic and Undiagnosed Conditions. 2019. Available at: https://actionforaccess.thesmarthub.com/custom/Downloads/GAUK_report-digital.pdf (accessed November 2020)