Imaginechina / Rex Features

Fake vials of cancer drug bevacizumab, containing no active ingredient, reached patients in the United States in 2012 and 2013 after being bought by doctors from unauthorised suppliers. The counterfeit products, branded as Avastin or its Turkish equivalent Altuzan, passed through a complicated web of distributers in the United States, as well as in Turkey, Egypt, Switzerland, Denmark and the UK. The fakes prompted the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue 949 safety notices to 932 doctors and clinics across 48 states and two territories in the United States. It is not known how many patients were affected and so far only 18 individuals have been prosecuted, including US and international suppliers, doctors and a pharmacist[1]

. The case highlights vulnerabilities in the global medicines supply chain as well as the transnational nature of the criminal trade in counterfeit medicines.

Avastin’s manufacturer Genentech is not the only company to find fake versions of its drugs on the market. US pharmaceutical giant Pfizer has found that 69 of its products were falsified in 107 countries in 2014, up from 29 products in 75 countries in 2008 — a doubling of the problem in six years. Over 700,000 deaths per annum from malaria and TB have been attributed to falsified medicines[2]

and the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest in the United States estimated that counterfeits cost the global economy around US$75bn in 2010.

The situation matches the definition of a pandemic perfectly, says Joel Breman, senior scientist emeritus at the National Institutes of Health’s Fogarty International Center: “An epidemic, occurring over a wide area, crossing international boundaries, and affecting a very large number of people.”

We are not seeing more reports just because everyone is more aware of the problem, says Gaurvika Nayyar, programme manager for the US Pharmacopeial Convention, which sets standards for the identity, strength, quality, and purity of medicines manufactured worldwide. Nayyar’s team has brought together a group of policy experts, lawyers, epidemiologists and public health professionals to devise a global response to the global problem. “The truth is that this is really just the tip of the iceberg,” she stresses. ”We’re seeing a lot of places that are reporting to the wrong agencies, or not reporting at all because the patients are often not alive to tell you that they received poor quality medicine.”

It is difficult to pin down the extent of counterfeiting globally. The available data come from a wide range of sources — reports from national medicines regulatory authorities, enforcement agencies, pharmaceutical companies, non-governmental organisations and other studies. Data are collected in different ways, so different studies cannot be compared directly. And while the data from one study are being analysed, the adaptable criminal will have moved on to the next project — a new medicine, a new manufacturing technique, or new markets.

Existing figures probably underestimate the problem, write Breman and colleagues in a special supplement on falsified medicines in the Journal of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

[3]

. “Incidents of distribution and use of poor-quality pharmaceuticals often go unreported because of poor surveillance systems and are kept from the public record by governments and pharmaceutical companies,” they warn.

Researchers at University of California, San Diego, have looked at the depth of counterfeit drug penetration in global legitimate medicine supply chains, based on data from the Pharmaceutical Security Institute, a body created by pharmaceutical companies to monitor the market for counterfeits[4]

. The big surprise for the researchers was just how little is known. “Nobody has a good idea of how big the problem really is,” said Tim Mackey, lead author and assistant professor of anaesthesiology and global public health at the university, in a statement. “The most important takeaway of our study is that we don’t have the necessary data or surveillance to effectuate meaningful public health interventions or policy change,” he added.

One of the problems with gathering data on medicines that have been intentionally fraudulently produced by criminals is the use of inconsistent terms to describe the problem: fake, spurious and counterfeit are just three of the more popular. “We should not get confused by so many other terms, which have hindered the movement in councils of discussion,” says Breman, who himself urges use of the World Health Organization (WHO) term ‘falsified’.

A PubMed search for falsified medicines between 1966 and 2015 shows that, since the year 2000, numbers of publications have almost doubled every five years[5]

.

Another major problem is the paucity of reliable and scalable technology to detect fakes before they reach patients, says Nayyar. She also cites the lack of regulatory and manufacturing frameworks to police the illicit trade, and too little focus on China and India, where most of the medicines, globally, are coming from.

If this pandemic goes unchecked, it will be devastating for all the progress that’s been made against malaria, HIV, and TB in developing countries, but also in other countries that previously didn’t have a problem, she adds. “Morbidity and mortality aren’t the biggest concerns, there’s also the issue of drug resistance, which will magnify the problem of poor quality medicines around the world.”

Global policing

One way of avoiding the confusion generated by numerous independent data sources is the involvement of a global agency. Interpol, the International Criminal Police Organization, is tackling the problem of pharmaceutical crime in three ways: coordinating operations in the field to disrupt transnational criminal networks; training crime-fighting agencies worldwide; and building partnerships across sectors.

Interpol has a membership of 190 countries, each of which maintains a National Central Bureau staffed by national law enforcement officers. The agency is seeing a significant increase in the manufacture, trade and distribution of counterfeit, stolen or illicit medicines and medical devices. It’s an increase compounded by the rise in internet trade, where drugs can be bought easily, cheaply and without a prescription.

Interpol is combating the online sale of counterfeit and illicit medicines through Operation Pangea, a global week of action that has taken place each year since 2008 (Table 1).

| Table 1. Data from Interpol’s Pangea II, with 25 participating countries, to Pangea VII, with 113 participating countries | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Interpol | ||||||

| Pangea II 2009 | Pangea III 2010 | Pangea IV 2011 | Pangea V 2012 | Pangea VI 2013 | Pangea VII 2014 | |

| Participating countries | 25 | 44 | 81 | 100 | 99 | 113 |

| Websites shut down | 153 | 297 | 13,495 | 18,629 | 13,763 | 11,863 |

| Packages inspected | 11,164 | 278,524 | 65,000 | 143,709 | 534,562 | 618,191 |

| Packages confiscated | 2,356 | 21,200 | 7,482 | 9,551 | 41,954 | 35,206 |

| Arrests | 12 | 87 | 92 | 169 | 213 | 434 |

| Medicines seized | – | 2,300,000 | 2,600,000 | 4,353,193 | 10,192,274 | 9,695,815 |

Nearly 200 enforcement agencies across 113 countries took part in the latest Operation Pangea (Pangea VII), which ran from 13–20 May 2014. Nearly 10 million medicines were seized, over 11,000 websites were shut down and 434 arrests were made. UK medicines regulator the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) played an important role in the operation, seizing £8.6m of counterfeit and unlicensed medicines in the UK, including huge hauls of potentially harmful slimming pills and controlled drugs such as diazepam and anabolic steroids. The majority of packages seized that contained medicines supplied illegally originated from India and China, with 72% and 11% of seizures originating from these countries, respectively.

“Counterfeit medicines are the number one black market of all crime,” says Mark Jackson, head of intelligence at the MHRA. Keeping ahead of the curve is essential, with the MHRA now seeing a worrying uptake in ‘smart drugs’ like methylphenidate alongside a host of other lifestyle drugs and treatments for life-threatening diseases, says Jackson. On top of this, the recent Ebola epidemic saw adaptable counterfeiters entering the market. Keeping close tabs on these and related activities is essential, he says, particularly through ongoing global operations like Interpol’s Pangea.

Fending off the fakers

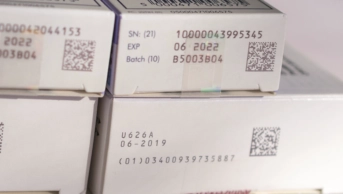

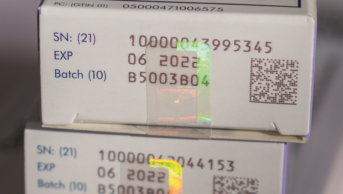

In order to stump counterfeiters, medicine manufacturers can incorporate difficult to copy features either into the medicine itself or on to the packaging.

There is an extensive range of shapes, sizes, colours, flavours, embossing and coatings available to tablet manufacturers. It’s something that the patient is more likely to see than the prescriber or pharmacist, and relies on patients who take their medicine regularly enough to recognise it. The effects can give instant reassurance to patients, and make copying difficult. There are also covert drug labels within the tablet — ‘micro taggants’ — that contain a code or picture that can only be seen under a microscope.

Altering the appearance, feel, or flavour of tablets is an extra cost that companies in developing countries, and generics companies, are unlikely to swallow. Packaging, which applies to all medicines not just tablets, is something that all drug manufacturers can, and should, be striving to make counterfeit proof. The information contained in effective packaging will also help identify substandard medicines.

Packaging, like banknotes, can incorporate printed patterns that are too intricate to copy easily, or can only be viewed under UV light. Packs can be folded in a distinct way or use particular inks in unique colours.

Aside from what they look like, packs can include information about exactly what the drug is and where and when it was made. Batch numbers were used traditionally, but they contain relatively limited information (one ‘lot’ may include thousands or tens of thousands of bottles) and they are easy to fake.

Trevor Jones, visiting professor at King’s College London, one-time director general of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), and a founder member of the not-for-profit Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV), is joining the call for a unique 2D barcode on each pack. They are not easy to fake, and can include all the information related to a medicine, from its manufacture right through to dispensing.

From 2018, when Europe’s Falsified Medicine’s Directive comes into force, every prescription-only medicine in the EU will have a unique serial number applied at the point of manufacture, which will most likely be displayed on the pack as a 2D barcode.

“We need a system that goes right back to the actual point where these things were made,” says Jones. “And not just in the developed world.” There is an argument that 2D technology may be beyond the resources of developing countries – this doesn’t wash with Jones. ”Most people in the developing world do have mobile phones,” he notes. The use of mobile phones — by doctors or pharmacists or, in some cases, patients — to read barcodes has been suggested previously by WHO working groups and others to make data both secure and accessible.

Time for action

The pharmaceutical industry is global, and a global common authentication system needs to be finalised and implemented urgently, says Jones. Global surveillance of supply chains needs to be improved, alongside active policing of counterfeit sources. To this end, WHO has developed a web-based monitoring and surveillance system dedicated to improving global intelligence and data collection to assess the scope, scale, and harm caused by spurious/falsely labelled/falsified/counterfeit (SFFC) medicines (see Table 2). A rapid alert form is completed and the information automatically populates a WHO database, with each incident having its own record and all data fields within the database being searchable. Since its roll out in July 2013, more than 625 suspected products have been reported from 73 countries, and nine WHO drug alerts have been issued as a result.

| Table 2: Examples of falsified medicines reported to the World Health Organization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Source: World Health Organization | ||

| SFFC medicine | Country/Year | Report |

| Avastin (for cancer) | United States, 2012/2013 | Affected 932 medical practices in the United States. The drug lacked active ingredient. |

| Viagra and Cialis (for erectile dysfunction) | UK, 2012 | Smuggled into the UK. Contained undeclared active ingredients with possible serious health risks to the consumer. |

| Truvada and Viread (for HIV/AIDS) | UK, 2011 | Seized before reaching patients. Diverted authentic product in falsified packaging. |

| Zidolam-N (for HIV/AIDS) | Kenya, 2011 | Nearly 3,000 patients affected by falsified batch of their antiretroviral therapy. |

| Alli (for weight loss) | United States, 2010 | Smuggled into the United States. Contained undeclared active ingredients with possible serious health risks to the consumer. |

| Anti-diabetic traditional medicine (for high blood sugar) | China, 2009 | Contained six times the normal dose of glibenclamide. Two people died, nine people were hospitalised. |

| Metakelfin (antimalarial) | United Republic of Tanzania, 2009 | Discovered in 40 pharmacies. The drug lacked sufficient active ingredient. |

Globalisation has redefined the field of medical product regulation by adding layers of complexity to the supply chain and creating opportunities for the potential contamination or intentional adulteration of the ingredients and finished products that pass through its links, writes Margaret Hamburg, the recently retired president of the FDA, in the foreword to the Journal of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene’s supplement on falsified medicines[6]

.

Source: epa european pressphoto agency b.v. / Alamy

Drug makers can design features to help thwart counterfeiters

In 2014, writes Hamburg, member states at the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution aimed at strengthening regulatory systems for medical products, which are fundamental in providing the oversight and enforcement needed to improve supply chain integrity. “This resolution is a global health milestone, providing a framework for collective action and representing a comprehensive systems approach that draws attention to emerging priorities and the core components required for effective medicines regulation.”

Jones says: “The time for ‘talk talk’ is over, let’s get on with the job.”

Substandard medicines

Substandard medicines are different to counterfeits but can result in similar problems because they contain too much or too little active ingredient. Substandard medicines are genuine medicines produced by authorised manufacturers that do not meet quality specifications set for them by national standards because of poor manufacturing procedures or degradation during transport and storage. Alarming reports have suggested that up to 35% of antimalarial drugs in malaria-endemic countries are fake[7]

. However, a study that is currently in press found that substandard antimalarials were more common than counterfeits in six malaria-endemic countries.

Harparkash Kaur, a chemist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in London, and her team, purchased more than 10,000 artemisinin-containing antimalarials from Cambodia, Ghana, Tanzania, Nigeria (Enugu and Ilorin) and Equatorial Guinea using a variety of sample-collecting approaches (openly explaining why drugs were being selected, or employing actors pretending to be patients). In previous studies, samples have predominantly been collected using the convenience approach, in which products are selected because of their convenient accessibility and proximity, and sometimes specifically because they looked likely to be counterfeit.

Kaur’s samples were analysed quantitatively using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and qualitatively using mass spectrometry, in three independent laboratories in the UK and the United States. The data show that, of the 10,092 samples analysed, 92.8% were authentic, 5.7% were substandard, 0.6% were degraded and just 1% were falsified.

“This type of study is very cost intensive, both for the purchase and analysis of drugs,” says Kaur, whose study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation. A luck of funds, particularly in developing countries, holds back research in this area.

“Just because we did not find any falsified drugs does not mean that we can be complacent,” she says. The presence of substandard medicines is definitely a concern.

References

[1] Mackey, TK, Cuomo R, Guerra C et al. After counterfeit Avastin — what have we learned and what can be done? Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2015;12:302–308.

[2] Mackey TK & Liang BA. The global counterfeit drug trade: patient safety and public health risks. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2011;100:4571–4579.

[3] Nayyar GML, Breman JG & Herrington J. The global pandemic of falsified medicines: laboratory and field innovations and policy perspectives: summary . Supplement to the American Journal of Tropical Hygiene and Medicine ‘The global pandemic of falsified medicines: laboratory and field innovations and policy perspectives’ 20 April 2015.

[4] Mackey TK, Liang BA & York P. Counterfeit drug penetration into global legitimate medicine supply chains: a global assessment . Supplement to the American Journal of Tropical Hygiene and Medicine ‘The global pandemic of falsified medicines: laboratory and field innovations and policy perspectives’ 20 April 2015.

[5] Nayyar GML, Attaran A, Clark JP et al. Responding to the pandemic of falsified medicines . Supplement to the American Journal of Tropical Hygiene and Medicine ‘The global pandemic of falsified medicines: laboratory and field innovations and policy perspectives’ 20 April 2015.

[6] Hamburg M. Foreword: the global pandemic of falsified medicines: laboratory and field innovations and policy implications. Supplement to the American Journal of Tropical Hygiene and Medicine ‘The global pandemic of falsified medicines: laboratory and field innovations and policy perspectives’ 20 April 2015.

[7] Nayyer GML, Breman JG, Newton P et al. Poor-quality antimalarial drugs in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2012;12:488–496.