On 30 September 2004, Vioxx (rofecoxib), a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that had been on the market since 1999, was suddenly withdrawn by its manufacturer MSD owing to concerns about its effect on cardiovascular health.

The legacy of this once-blockbuster drug has been a reshaping of the medicines regulatory system and a re-evaluation, not only of cyclo-oxygenase(COX)-2 inhibitors (like Vioxx) but of the whole class.

“The Vioxx debate did emphasise that there were anxieties for all NSAIDs and caused a re-examination of the whole prescribing of the class,” says Alan Silman, who was then a consultant rheumatologist and is now medical director at Arthritis Research UK. “Why risk even a small chance of a serious event, like a cardiovascular event, for drugs giving symptom relief and not affecting disease outcome?”

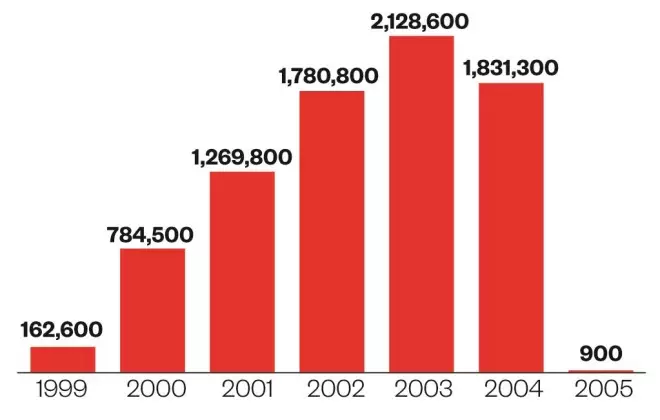

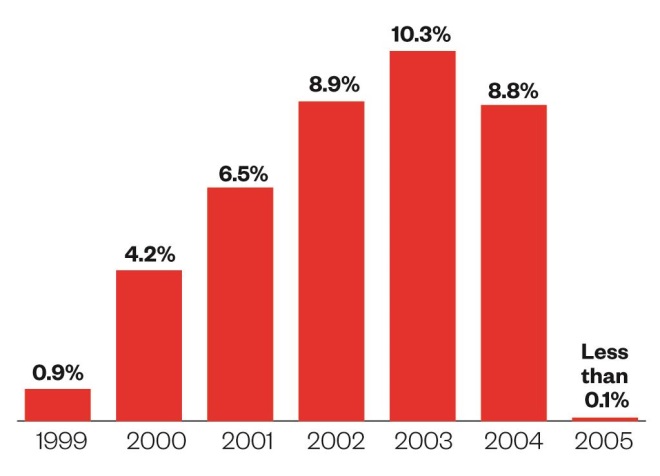

At the height of its eminence in 2003, Vioxx represented 10.3% of all NSAID prescriptions in England, with more than 2.1 million prescriptions dispensed[1]

. More than 2.5 million prescription items of a competing COX-2 product, Celebrex (celecoxib), which was launched soon after Vioxx, were dispensed in England in 2004. However, in 2005, the year after Vioxx’s withdrawal, prescriptions for Celebrex had fallen to around 800,000. Although it’s still on the market today, by 2013, the number of Celebrex prescriptions had fallen to just under 340,000.

In 1999, there were some 18.5 million prescription items dispensed for the NSAID class, including COX-2 inhibitors, but this fell to 15.5 million items1 in 2013.

Regulators are still assessing the safety of NSAIDs — as recently as June 2014, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) announced it was reviewing high-dose ibuprofen (see timeline).

Unknown risks

In the 1990s, there was tremendous hope that safer drugs could be developed to treat osteoarthritis and other painful conditions because NSAIDs were linked with adverse gastrointestinal (GI) side effects. “The medical community and society had always felt the need for safer NSAIDs,” says Silman.

“The ones that were really effective for joint pain struggled because there was this association with GI side effects, such as ulcers, bleeds and perforations,” he says.

So when the promise emerged of selective COX-2 inhibitors, a subclass of NSAIDs, without the GI side-effects, they were welcomed by the musculoskeletal community. “There was a sense that COX-2 inhibitors could be a major advance for patients with osteoarthritis,” Silman says, speaking from personal observations.

However, doctors were not aware of the cardiovascular risks associated with COX-2 inhibitors, let alone with NSAIDs.

The story of Vioxx’s decline starts in 2000 with the publication of a key study called VIGOR (the Vioxx gastrointestinal outcomes research trial). In order to show Vioxx reduced GI events compared with non-selective NSAIDs, MSD (known as Merck in the US and Canada), conducted a large clinical trial comparing Vioxx with naproxen in rheumatoid arthritis patients.

VIGOR found that Vioxx had similar efficacy to naproxen, with significantly fewer GI events. But there was a major problem. While there were similar overall mortality rates, myocardial infarctions were four times higher in the Vioxx arm compared with naproxen (0.4% versus 0.1%)[2]

.

Debate raged as to whether naproxen was providing a cardioprotective effect, similar to that seen with aspirin. However, regulators strengthened precautions on Vioxx’s label to reflect new cardiovascular and GI safety information (see timeline).

Patients need to know about risks. This is about making sure patients can make informed decisions and know the risks

It was the results of another large MSD-sponsored trial, called APPROVe, which led the company to withdraw the product.

APPROVe was supposed to help win another indication for Vioxx for the prevention of the recurrence of precancerous growths in the colon. But the results showed a two-fold increase in the risk of adverse cardiovascular events in patients taking Vioxx compared with placebo: 46 patients taking Vioxx had a serious thrombotic event compared with 26 in the placebo arm. The difference was only apparent after 18 months of treatment[3]

. As a result, the study was stopped early and MSD withdrew Vioxx.

Harlan Krumholz, professor of cardiology at Yale’s School of Medicine

“It took a long time for the risks surrounding Vioxx to emerge,” says Harlan Krumholz, a professor of medicine (cardiology) at Yale’s medical school who has published numerous papers on Vioxx and has provided expert testimony in two US trials on behalf of patients who had taken the drug.

Krumholz conducted an analysis[4]

of published and unpublished trials in 2009, which indicated that the cardiovascular harm signal for Vioxx compared with placebo could have been highlighted as early as 2001. Data used in the analysis were not publicly available when rofecoxib was being marketed but became available later through litigation.

In December 2005, it emerged that three additional myocardial infarction events that had occurred in the Vioxx arm of the VIGOR trial had not been included in the published paper, calling into the question the integrity of the rest of the data[5]

.

Silman, who sat on the trial’s data safety monitoring (DSM) committee, says: “It is clear to us in retrospect that we probably didn’t have all the information we needed to do our job properly.”

He believes members of the committee were vulnerable to criticism because they were paid by MSD to participate in the committee, but also to be independent. Silman has not sat on an industry-funded DSM committee since.

The ups and downs

Source: National archives; HSCIC

Number of Vioxx (rofecoxib) prescription items dispensed in the community in England

Big problem

Source: National archives, HSCIC

Proportion of all NSAID prescription items dispensed that were Vioxx

The fall-out

After Vioxx was withdrawn, there were numerous papers and discussion on the increased risk of cardiovascular events with all NSAIDS and labelling changes were made. However, Silman argues that it has still not been proven in observational studies that Vioxx’s cardiovascular events were any higher than, for instance, diclofenac, a popular non-selective NSAID.

It proved to be complex: not all COX-2 inhibitors have the same cardiovascular risks and not all non-selective NSAIDs have the same cardiovascular risks. “If the VIGOR study had been comparing Vioxx against diclofenac, it is entirely plausible that it would have shown no difference in cardiovascular events,” Silman points out.

It is not possible to say how many people in the UK might have died as a result of taking Vioxx, but the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) says it is estimated that COX-2 inhibitors may be associated with about three additional thrombotic events, such as heart attack and stroke, per 1,000 patients per year in the general population.

In a testimony to the US senate committee shortly after Vioxx was withdrawn, David Graham, then associate director for science and medicine in the US Food Drug Administration’s office of drug safety, estimated that between 88,000 and 139,000 people in the United States had suffered a heart attack or stroke as a result of taking Vioxx, with 30 to 40% of these “probably” dying[6]

.

MSD is still fighting a slew of lawsuits worldwide[7]

— Vioxx made MSD some US$11bn in revenue during its marketing, but has reportedly already cost it nearly $6bn in litigation[8]

[9]

one of the largest settlements being with the US government in 2011 at $950m.

MSD would not tell The Pharmaceutical Journal how much it has paid out to date. The company believes it acted responsibly with Vioxx “from the careful study in clinical trials involving about 10,000 patients before its approval by regulatory authorities around the world, through the careful safety monitoring while Vioxx was on the market, right up through the decision to voluntarily withdraw the medicine in September 2004”, according to a spokesperson.

Chris Deighton, a consultant rheumatologist at the Royal Derby Hospital, who is a former president of the British Society for Rheumatology, says the Vioxx experience made society more conscious that it might not be seeing all the necessary data when it came to company-sponsored randomised clinical trials.

Deighton thinks clinical trial data are now scrutinised more closely by drug regulators. The UK’s MHRA, which acted as the reference member state for approval of Vioxx in Europe, conducted an investigation into the alleged withholding of data by the company which it completed in November 2006, but there was “insufficient evidence to bring a prosecution”.

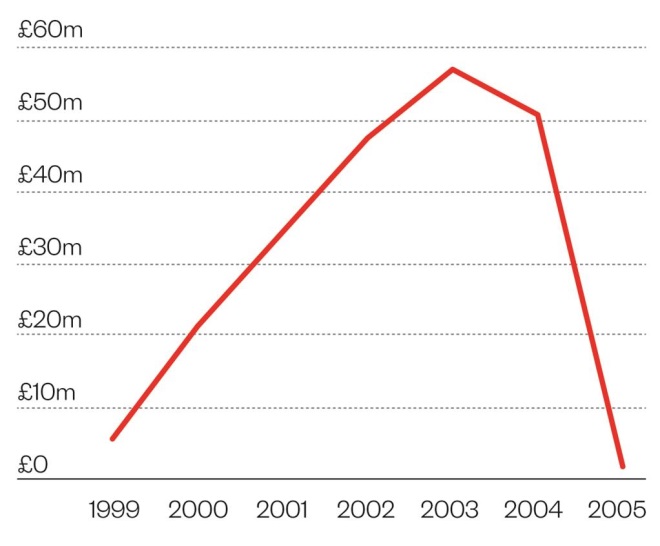

Expensive business

Source: National archives, HSCIC

Cost of net ingredient in Vioxx in England

Revamp pharmacovigilance

The MHRA says the withdrawal of Vioxx was a “significant” drug safety issue which helped inform the evolution of regulatory pharmacovigilance in the EU. Pharmacovigilance has now changed from a system based largely on risk detection using individual case reports from healthcare professionals to proactive benefit risk management throughout a medicine’s existence.

New EU pharmacovigilance legislation came into force in mid-2012, after a review of drug safety systems in 2005. Its objectives are the better collection of data, improved analysis and timeliness of procedures and greater transparency. It also created the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC), which assesses the risk management of medicines for Europe.

“[The legislation] was the biggest change to the legal framework for human medicines since the creation of the EMA in the mid-1990s,” says Noel Wathion, its chief advisor on policy. Over the past ten years, the system of safety monitoring of medicines has been fundamentally re-shaped, he says, allowing for a more proactive management of potential safety concerns and strengthened post-marketing surveillance of medicines.

The EMA has also been attempting to increase transparency around clinical trial data — not as a direct consequence of the Vioxx event but to establish “trust and confidence in the system”.

In doubt

Ten years on, scientists are still debating whether MSD should have withdrawn Vioxx, with some arguing that it was a mistake.

Usually withdrawals occur in a step-wise fashion, says Richard Bergström, the director general of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA). You start with some restrictions on the use of the product, move it to second-line use, then third-line use and then withdraw it completely.

“It is still too early to tell whether it was the right decision as we still don’t know why certain patients have side effects from a drug while others do not,” Bergström admits.

“I would have advocated that Merck not withdraw it but rather release all data about the drug instead,” says Krumholz.

He points out that some patients are willing to take a drug even if they have a cardiovascular risk factor. “Patients need to know about risks. This is about making sure patients can make informed decisions and know the risks. In this case there is good evidence that there is a 30% higher risk of cardiovascular event with a drug like Vioxx,” Krumholz argues.

The joke at the time of its withdrawal was that every rheumatologist was stockpiling Vioxx because of its efficacy

Neither does Silman think Vioxx should have been withdrawn, since it proved to be a very effective anti-inflammatory drug. “The joke at the time of its withdrawal was that every rheumatologist was stockpiling Vioxx because of its efficacy.” The Vioxx story is not so simple and it was not about “Vioxx being the bad guy”, he says.

If MSD had not withdrawn the drug, perhaps regulators would have deemed that it not be used in patients with pre-existing heart conditions and the elderly, Silman ponders. “It was not necessarily a given that Vioxx should have been withdrawn completely. For instance, diclofenac has not been withdrawn and is still on the market but with advice to use with caution,” he says.

Richard Bergström, director general of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations

For Bergström, Vioxx represented the “first real loss of a modern blockbuster medicine” that came out in the 1980s and 1990s, before industry subsequently lost other products such as Avandia (rosiglitazone) and Reductil (sibutramine). “It started a whole new reflection on whether we glossed over the science or not, and contributed to the obsession industry now has with capturing real time data on medicines,” he says.

For industry, data mining on the real use of a product, as opposed to relying on data from clinical trials, will complement spontaneous adverse drug reaction (ADR) reports to provide real data on effectiveness and safety to payers and reimbursement bodies.

Vioxx changed the way pharmacovigilance departments operated within companies and it contributed to a greater emphasis in place now on the role of risk management plans — studies that companies must do after a product gains a licence, rather than relying on ADR reporting.

“Vioxx, along with the Mediator (benfluorex) affair [in 2009] in France, both contributed to the new strengthened pharmacovigilance system that we have in the EU, which came into effect in 2012,” Bergström says.

Safety signals

Normally, society relies on ADR monitoring to pick up drug safety signals, but with Vioxx, it was the APPROVe trial that led to the withdrawal of the product.

Krumholz believes that ADR surveillance is “wholly inadequate”, adding that Vioxx’s cardiovascular events would not have been picked up by ADR reports. “When you have a common problem like heart attack, it is unlikely that clinicians would report it and know it was caused by a drug. We need sophisticated analysis of clinical practice data.” He advocates “big data” initiatives, which leverage data from real-world practice, to help pharmacovigilance activities.

Silman agrees: “[If] you come across a heart attack or cancer, which is so common, would you attribute the cause to a drug that has been taken for a few years. It is difficult to attribute common morbid events as ADR events.” That can only be done with large-scale observational studies, he says, adding that society needs to take advantage of large datasets, such as “care.data” and the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, to identify risks.

Avoiding repeats

The possibility of another Vioxx is real because not all adverse reactions are known at the time a medicine is licensed. There are numerous medicines out there and we still don’t know their full risks. The answer lies with risk-management plans, improved transparency, and using big data to help scientists understand the risks about medicines in the real world.

Krumholz thinks it is not a story about a “bad company, but about human nature”. In all the internal MSD emails that he read during the trial, there were no MSD employees who he perceived as being out to harm people. “People believed in the drug. There will always be people in companies who get overexcited about a product and over-reach its benefits, but this needs to be curbed by independent analysis.”

Elizabeth Sukkar is a news editor for The Pharmaceutical Journal.

Timeline

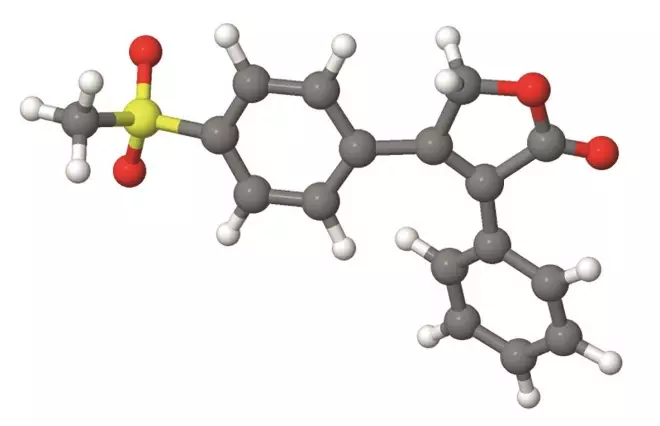

Source: Tarique012 / Wikimedia Commons

1999: Vioxx launched for osteoarthritis, adult pain, menstrual pain.

November 2000: VIGOR published, showing greater number of heart attacks in patients taking Vioxx than naproxen.

April 2002: Vioxx labelling changes made in the US because of VIGOR data.

November 2003: European Medicines Agency (EMA) concludes review of COX-2s, saying benefits outweigh the risks; caution is advised for patients who have history of GI or heart problems and are taking aspirin.

27 September 2004: MSD contacts US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to discuss the data safety monitoring board’s decision to halt its APPROVe study on Vioxx as it showed an increase in cardiovascular risk and stroke. This was the first demonstration of a difference in comparison to a placebo and supported the signal from the VIGOR trial.

30 September 2004: MSD voluntarily withdraws Vioxx worldwide.

October 2004: EMA starts review of all COX-2s.

June 2005: EMA’s review shows increased risk of cardiovascular ADRs for COX-2s. EMA suspends marketing authorisation for valdecoxib (Bextra) and adds new contraindications and warnings for other COX-2s available in the EU.

October 2005: EMA concludes review of non-selective NSAIDs, and finds no new safety concerns.

October 2006: Based on new data, EMA says there is a possibility of a small increased risk of thrombotic events for some non-selective NSAIDs, particularly when used at high doses and for long periods.

October 2011: Because of new studies, EMA starts a new review of cardiovascular safety for non-selective NSAIDs.

Source: Shutterstock.com

October 2012: EMA concludes review, saying new data confirms cardiovascular findings for non-selective NSAIDs found in 2005 and 2006. Recommends that the pharmacovigilance risk assessment (PRAC) committee assesses diclofenac.

June 2013: EU’s PRAC concludes diclofenac review: says the benefits still outweigh risks, but it is associated with a similar cardiovascular risk to COX-2s. Product information updated.

June 2014: EMA initiates review of high-dose ibuprofen (2,400 mg per day), following concerns it could have a similar cardiovascular risk to COX-2s. It will also review data on the interaction of ibuprofen with low-dose aspirin.

References

[1] Prescription Cost Analysis England 2013. Health and Social Care Information Centre. (accessed 18 September 2014).

[2] Bombardier C et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. New England Journal of Medicine 2000;343:1520–1528.

[3] Bresalier RS et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. New England Journal of Medicine 2005;352:1092–1102.

[4] Ross JS et al. Pooled analysis of rofecoxib placebo-controlled clinical trial data: lessons for postmarket pharmaceutical safety surveillance. Archives of Internal Medicine 2009;169:1976.

[5] Curfman GD et al. Expression of concern: Bombardier et al. “Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” New England Journal of Medicine 2000;343:1520–1528. New England Journal of Medicine 2005;353:2813–2814.

[6] Testimony of David J. Graham to the US senate committee on finance on 18 November 2004. (accessed 18 September 2014).

[7] 2013 Merck Annual Report (accessed 18 September 2014).

[8] Loftus P & Kendall B. Merck to Pay $950 Million in Vioxx Settlement. Wall Street Journal. 23 November 2014. (accessed 8 September 2014).

[9] Feeley J. Merck Pays $23 Million to End Vioxx Drug-Purchase Suits. Bloomberg . 19 July 2013. (accessed 8 September 2014).