Administration of morphine following nerve injury can prolong the duration of pain, even after treatment has stopped, a study in rats has found.

Lead author Peter Grace from the University of Colorado in Boulder and team have shown for the first time that pain can last for months after morphine treatment has ended

The researchers say that such an effect has not previously been observed with opioid drugs and is concerning given their widespread use in pain management.

“It was known that opioids caused an increase in pain sensitivity, but prior studies had only investigated the time when opioids were still in the system,” says lead author Peter Grace from the University of Colorado in Boulder. “Here, we show for the first time that the pain lasts for months after the morphine treatment ends.”

Reporting their findings in PNAS

[1]

(online, 31 May 2016), the team first looked at the effect of a five-day course of morphine administered following sciatic chronic constriction injury. They found that it doubled the duration of nociceptive sensitisation compared with rats who received a saline placebo.

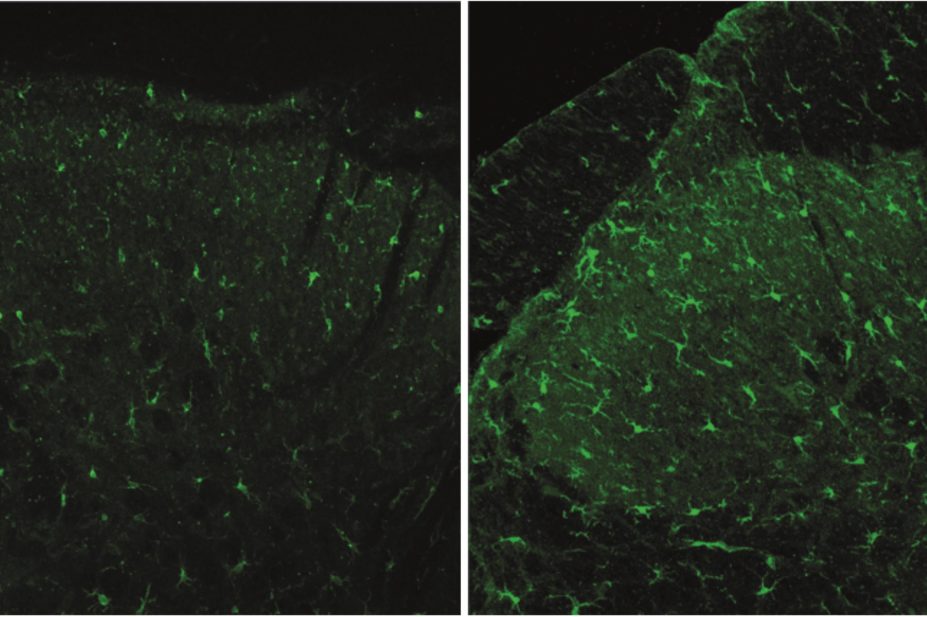

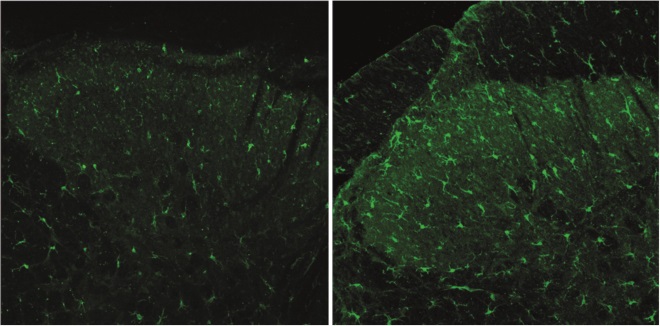

The researchers then explored the mechanism behind this and found that it was mediated by signalling pathways involving spinal microglia. They found that morphine activates inflammasomes in the spinal cord known as NLRP3, and that pharmacologically inhibiting this process can prevent or reverse morphine-induced pain sensitisation.

CD11b expression in the dorsal horn, five weeks after morphine (pictured right) or saline (left) treatment concluded, illustrating peripheral nerve injury. The morphine treatment prolonged the microglial activation

They say the data support a recently proposed “two-hit hypothesis” whereby microglia are activated by the first hit – nerve injury – resulting in an exaggerated reaction to the second hit – morphine.

“The implications of such potent microglial ‘priming’ has fundamental clinical implications for pain and may extend to many chronic neurological disorders,” the researchers say.

Catherine Stannard, consultant in pain medicine at Southmead Hospital, Bristol, says that while the study on short-term experimental pain is interesting, persistent pain in adult humans is more complex

However, Catherine Stannard, consultant in pain medicine at Southmead Hospital, Bristol, says that while the findings are interesting, they cannot easily be extrapolated to humans.

“This is a short-term experimental pain, whereas persistent pain in adult humans – the sort in people using opioids in the long-term – is much, much more complex; it’s more driven by emotions and distress and experiences, and so on.”

Stannard says that findings like this might come up in conversations with patients about whether or not to begin opioid treatment but they also have the potential to distract prescribers from addressing the real reasons why a patient’s pain is not responding to opioids.

“Scientifically, it tells us a bit more, and adds to this rather difficult picture, trying to understand about opioid-induced hyperalgesia, but I think in reality it doesn’t really help much more in terms of understanding why complex patients get stuck on opioids in the long term that don’t work,” she says.

Stannard is involved in a project called Opioids Aware, funded by Public Health England, that aims to address an increase in opioid prescribing for long-term pain for which there is little evidence of efficacy. “Chronic pain is just a different condition to acute pain,” she says. Stannard believes the problem is not a lack of caution around prescribing opioids, but that many prescribers may not have enough information about the potential inefficacy and harm of the drugs.

She adds that pharmacists have an important role to play in promoting the appropriate prescribing of opioids, and that it is important for community pharmacists to feel empowered to query GPs when they spot prescribing that does not seem in line with best practice.

“Pharmacists, if they have time, can have the conversation with patients — is this working, is this taking away your pain? It’s a really good opportunity.”

In a separate study[2]

, presented at the Euroanaesthesia conference held in London on 27–30 May 2016, researchers found that patients undergoing surgery for breast cancer needed less postoperative pain relief if they received opioid-free anaesthesia.

Among 64 women undergoing lumpectomy or mastectomy, those who received opioid-free anaesthesia used an average of 8.1mg piritramide via patient-controlled pump in the 24-hour post-operative period, compared with 13.1mg among patients who received opioid anaesthesia.

The researchers say the findings suggest an “interesting benefit” to non-opioid anaesthesia, which can also help avoid other opioid-related side effects, such as post-operative nausea. However, they add that further research is needed before opioid-free anaesthesia could be recommended for all breast cancer patients.

References

[1] Grace PM, Strand KA, Galer EL et al. Morphine paradoxically prolongs neuropathic pain in rats by amplifying spinal NLRP3 inflammasome activation. PNAS 2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602070113

[2] Saxena S, Hontoir S, Gatto P et al. Comparing analgesic requirements after a non-opiate anesthesia and an opiate anesthesia in breast cancer patients: a prospective randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial. Presented at: Euroanaesthesia; 27–30 May 2016; London, UK.