Hunterian Museum

On 23 March 1885 almost 100,000 protesters marched through the city of Leicester where they hanged then beheaded an effigy of their common enemy. The dummy they decapitated did not depict an unpopular politician or a foreign foe, but the medical pioneer Edward Jenner.

The demonstration, which drew supporters from all over the UK, was the culmination of decades of public opposition to compulsory vaccination against smallpox. Leicester had become a hotbed of rebellion enflamed by determined health officials who prosecuted — and even imprisoned — thousands of parents for refusing to vaccinate their children.

Most of us today regard the discovery of vaccination as an indisputable public health triumph, which has led to millions of lives being saved, not least through the eradication of smallpox. Yet, as this small but powerful exhibition in the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London makes clear, the history of vaccination is marked by furious — and often violent — struggle between public and state.

Courtesy of the Hunterian Museum / On loan from Edward Jenner’s House, Museum and Garden

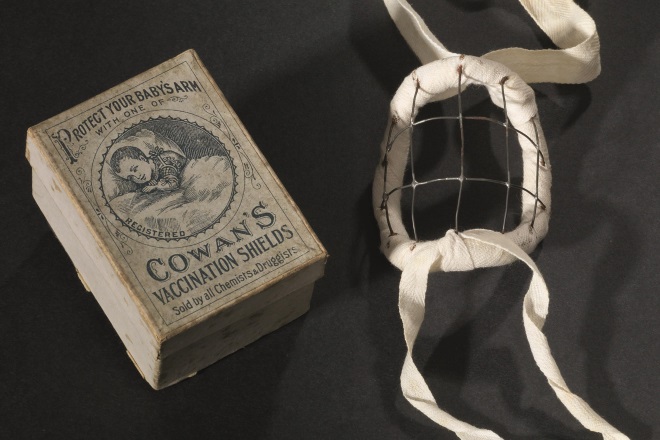

Vaccination shields (circa 1891) were used to protect the patient’s skin from damage or infection following the procedure

The exhibition ‘Vaccination: medicine and the masses’ walks us through the story of vaccination with a particular focus on smallpox. The origins of smallpox are unclear but the disease has been detected in Egyptian mummies dating to 1157 BC. By the 18th century smallpox was the single biggest cause of death in Europe, responsible not only for killing 60 million people but for disfiguring many more, blighting the marriage chances of countless Georgian women.

One poignant specimen from the anatomist John Hunter’s original collection shows a child’s scarred face while another reveals a portion of skin with vivid scarlet pustules. A wax model created by the renowned modeller Joseph Townes depicts a baby’s leg covered with smallpox blisters.

Inoculation, using matter from a smallpox pustule, was commonly used by lay healers in China, India, Africa and the Ottoman Empire long before it was imported to England in 1721 by the writer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the English ambassador to Turkey. She had to battle the medical establishment to establish inoculation in Britain. The idea of inoculating people using cowpox — a much milder disease in humans than smallpox — developed from folk practices, too. Several lay people, including Dorset farmer Benjamin Jesty, successfully inoculated people against smallpox using matter from cowpox pustules before Jenner tested the idea.

It was Jenner, however, who proved the efficacy of inoculation with cow pox — named vaccination from the Latin ‘vacca’ for cow — to the satisfaction of the medical profession after testing the method on an eight-year-old boy in 1796. The exhibition includes the immortal letter from his former teacher, Hunter, urging him to ‘trie the expt’ as well as Jenner’s triumphant letter announcing his success. Yet now that doctors had the upper hand in the battle against smallpox, the battle with the public began.

Courtesy of the Hunterian Museum

Vaccination was vehemently resisted from the start. Some were worried the vaccination method could introduce other diseases while religious leaders objected to the use of animal products. Once the government made vaccination compulsory for babies under four months in 1853 and introduced penalties for non-compliance in 1867, the campaign intensified. Anti-vaccination leagues sprung up all over the country in protest at state interference in parental rights. Rallies and demonstrations turned violent. Vicious cartoons, featured in the exhibition, showed John Bull imprisoned in ‘medical fetters’ and truncheon-wielding police officers rounding up children ‘to POISON their BLOOD’ and ‘make FEES for doctors’.

As parents defied the law so smallpox thrived. The exhibition’s most moving items are pitiful photographs taken in Leicester’s isolation hospital by the doctor in charge in the 1890s. They show children and adults covered with pustules or scarred for life side-by-side with healthy siblings and offspring who had been vaccinated. Finally the government had to admit defeat and compulsory vaccination was abolished in 1907.

From that point onwards public health officials had to rely on education and propaganda such as the 1951 public service film ‘Surprise attack’, which exploited post-war fears of foreign invasion in its melodramatic story of a girl infected by a ragdoll brought back from the East. British governments would never attempt compulsory vaccination again although — as the recent furore over the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine demonstrates – the debate over government intervention in public health remains as controversial as ever.

‘Vaccination: medicine and the masses’ runs until 17 September 2016 in the Hunterian Museum, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London WC2A 3PE. Entrance free.

You may also be interested in

‘Are people believing this information?’: research raises concerns over online drug marketing

Dale and Appelbe’s Pharmacy and Medicines Law: covering ‘essential ground in the most highly regulated areas of healthcare’