Shutterstock.com

The threat of patients taking counterfeit medicines continues to be a growing problem as counterfeiters find ever more sophisticated methods to contaminate the medicines supply chain. The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union adopted the Falsified Medicines Directive in 2011. In 2018, the full requirements, yet to be decided, will be implemented.

Every pharmacy across the EU will be affected by this directive. Indeed, the impact is potentially substantial, depending on the stipulations that will soon be determined by the European Commission.

The ultimate aim of this directive is to improve patient safety, but this cannot be achieved if it is not implemented properly and if pharmacists find it difficult to comply with the requirements.

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that up to 1% of medicines available in the developed world are likely to be counterfeit. This figure increases to 10% on a global scale. The multi billion pound global pharmaceutical market is attractive to criminals who seek to exploit weaknesses in global supply chains to insert their illicit and dangerous products. Many more medicines used by patients in the UK are now manufactured overseas, and travel to this country by long and sometimes vulnerable supply chains. The economic consequence of counterfeiting is well understood, such as undermining innovation. But with medicines, there is the additional danger of patient harm. This risk could come from the lack of an active ingredient or from the introduction of a toxic substance into the formulation.

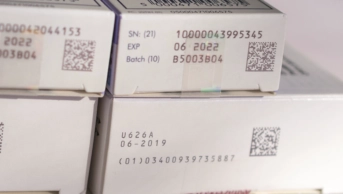

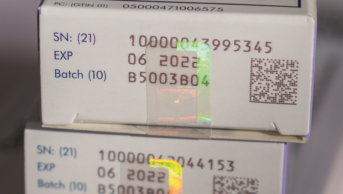

The directive calls for medicines to have a unique serial number applied at the point of manufacture, and this will almost certainly be displayed on the pack via a 2D barcode. All prescription-only medicines (POM) will be included unless a risk assessment excludes them (a ‘white list’ has been created to include POMs that are exempt from the unique serial number) and all over-the-counter medicines will be excluded unless deemed particularly vulnerable (these products will appear on the ‘black list’). This unique serial number will then be placed on to a database. At some point before the supply to the patient, the product will be scanned and the unique number will be checked against the database. This serial number will be deleted from the database so that it cannot be used to authenticate any other products. Products must also carry a tamper evident seal.

Important technical details, such as the identity of products on the white and black lists, are currently being considered by the European Commission as part of the process of issuing the ‘Delegated Acts’. This legal instrument, likely to be published in early 2015, will initiate the three-year countdown to implementation at EU member state level.

Supply chain stakeholders — branded manufacturers, wholesalers, parallel traders and pharmacies — have already started considering how this legislation can be implemented. The stakeholders that will engage with the system on a daily basis argue that they should lead this important IT project, rather than it be controlled centrally by the EU Commission. As a result, the supply chain players (including the Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union, on which the National Pharmacy Association (NPA), the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) and the Pharmaceutical Society of Northern Ireland are the UK representatives) are developing a stakeholder-led model for the authentication process.

Under this model, it is proposed that manufacturers will feed unique serial numbers into an EU Hub database. This will then distribute the numbers to a stakeholder-led database in the local market. This two-level system is required to accommodate parallel trade and manage multi-country packs.

The stakeholders agree that commercial data on the database, such as pharmacy dispensing data, is owned by the organisation that put it there. Discussions have already started between the UK organisations linked to the European stakeholders, including the NPA and the RPS, exploring how the UK database could be developed.

Unanswered questions

So progress has been made by the stakeholders on establishing the databases — but many important questions remain unanswered.

The European Commission is yet to confirm where the process of authentication will take place. Some within community pharmacy in the UK have suggested that wholesalers should do the scanning and present pharmacies with an authenticated product. This would reduce the burden on community pharmacy. Others argue enthusiastically for pharmacy level scanning, which could deliver electronic accuracy checking, better stock control and a more robust system of dealing with recalled medicines.

If the scans are to be done in the pharmacy, then when should they be done? Scanning as the product enters the dispensary would minimise the risk of interrupting the dispensing process, but deliver little in the way of additional benefits. Integrating the scan into the dispensing process will allow an electronic accuracy check that could free staff for other work, but could create delays in an already pressured environment.

And finally, the white and black lists. The European Commission (EC) is considering whether some products should be classified as being at low risk of being counterfeited and should therefore be exempt from the requirements to have a unique serial number and a barcode. The EC would exclude products based on a low price, the nature of the clinical indication and if there had been no previous cases of the medicine being counterfeited.

Low price is not always a deterrent to counterfeiters – fake aspirin was found in France in 2013. The proposed pricing threshold of around £4 would put vast numbers of prescription medicines out of scope and therefore exempt from the requirement to carry an authentication barcode. This may deliver some cost savings for manufacturers, but paradoxically could prove costly in community pharmacy. Dispensary staff would have to assess every medicine individually to determine whether it needs to be scanned. To make scanning feasible, there needs to be a single approach. Either all dispensary products should have a barcode – and therefore should be scanned – or none.

Given the worldwide scope of the problem, it is reasonable for a super-national body such as the EU to work across its member states and with other trading blocks to increase protection for the public from dangerous products. But the implementation of this directive must be viable and cost-effective. Now is the time for pharmacists to consider the implications of these new regulations for their practice and have their say, ensuring that they maximise the benefits of this directive and minimise the risks to patients. For good or ill, the EU regulations on counterfeit medicines will have a huge impact on UK pharmacies.

Gareth Jones is public affairs manager at the National Pharmacy Association.

NPA members can have their say through the organisation’s policy consultation on the Falsified Medicines Directive by contacting independentsvoice@npa.co.uk.

Royal Pharmaceutical Society members should get in contact with Charles Willis, head of public affairs (email Charles.willis@rpharms.com), to give their views and suggestions on the implementation of the Falsified Medicines Directive in the UK.