Shutterstock /JL

There have been significant increases in opioid prescribing in the UK over the past 15–20 years. The number of prescriptions for co-codamol, for example, has increased from 9 million in 2001 to 15 million in 2011, and there was a tenfold increase in tramadol prescribing between 1994 and 2009. The majority of such prescriptions are issued to people with chronic non-cancer pain[1]

,[2]

,[3]

, despite increasing concern over the lack of evidence to support opioid use at all in managing this type of pain[4]

.

Use of opioids for periods longer than around 16 weeks has been associated with limited clinical benefit and significant risk of harm[5]

, including the development of comorbid conditions, such as endocrine dysfunction[6]

and depression[7]

. We must learn from the well-documented opioid problems in the United States[8]

to avoid an ‘opioid crisis’ of our own.

The increasing use of opioids may be the result of a growing awareness of chronic pain as a long-term condition in its own right, like diabetes or heart failure, that needs to be managed[9]

. Once clinicians recognise a condition, they can feel obliged to treat it, even in the face of a poor evidence base.

The GP is the main source of support for most people living with pain[10]

, but, in a time-constrained environment, they may not be able to sufficiently explore non-medical approaches that will allow the patient a better quality of life. Medicines can be an easier option for both patient and prescriber[11]

, even when the prescriber knows that non-pharmacological alternatives may be more beneficial in the long term[12]

.

Prescribers’ knowledge may also be limited by their undergraduate training on pain. Teaching for pharmacists and doctors still predominantly concentrates on acute or palliative pain models. Yet, in the UK, chronic non-cancer pain is the most prevalent pain type — with as much as 43% of the population affected[13]

— and the most prevalent symptomatic long-term condition[14]

. Still, opioids are commonly prescribed to treat the condition[1]

,[6]

,[7]

and it appears that many healthcare professionals are unaware of the long-term harm of opioid use. The prescribing of doses that do not help the patient to improve their function is common[15]

.

Pharmacists may be well placed to offer meaningful intervention and support for people using opioid medicines for chronic, non-cancer pain in community pharmacy and primary and secondary care, but they must also be well equipped. We propose three main areas where pharmacists can promote safer use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: addressing the knowledge gap; regular reviews; and involving patients.

Addressing the knowledge gap

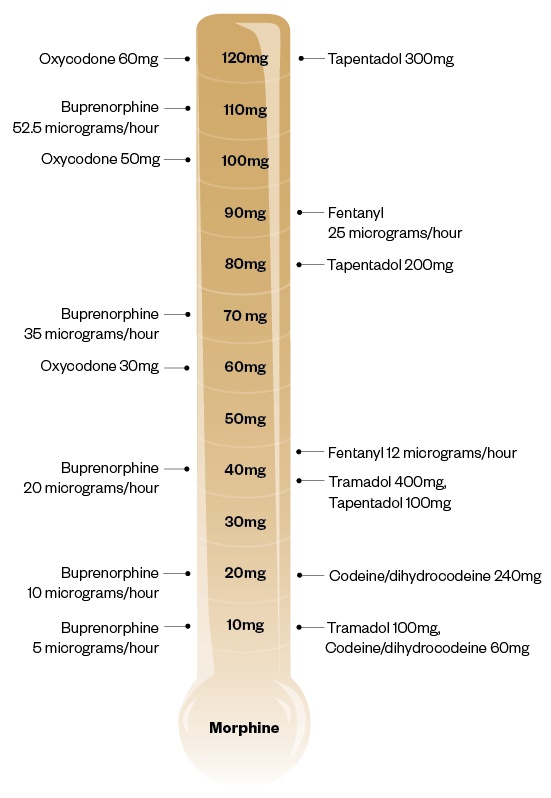

The British Pain Society recommends that the maximum dose of an opioid for chronic non-cancer pain should be 120mg ‘morphine equivalent dose’ (MED) per day. Above this dose, analgesic and functional benefits are limited and the risk of harm rapidly increases[16]

. But the concept of MED is not well understood by all prescribers[17]

.

Clinicians may have difficulty understanding what is considered a high dose, which can make it difficult to explain the potential problems of continuing current prescribing to the patient[18]

. A pharmacist may find it difficult to check prescriptions and highlight concerns about escalation or continued use of doses above the recommended maximum if they are not exactly sure where the lines are drawn.

The thermometer helps to identify where a person’s opioid prescription sits on the scale

To counter this problem, we have designed the opioid thermometer — a visual aide-memoire based on estimated dose equivalences and maximum opioid doses found in sources, such as the BNF and summaries of product characteristics (see Figure). The thermometer supports the understanding of opioid equivalence and helps to quickly identify where a person’s opioid prescription ‘sits’ on the scale. It can also help to demonstrate to prescribers how multiple opioids on a single prescription might add up to a large overall intake. It is not intended to be used to guide switches between different opioids, but may be helpful when comparing commonly used opioids in terms of morphine equivalence. It includes non-oral formulations, such as transdermal preparations, and challenges the assumption that they may be less harmful.

Figure: Opioid equivalence thermometer

Source: JL / The Pharmaceutical Journal

A memory aid for estimated dose equivalences and maximum opioid doses (this is not intended for use to calculate doses or for switching to alternative opioid medicines)

Familiarisation with opioid dose equivalences may increase the pharmacist’s confidence to identify a high dose and warn about potentially harmful rapid escalations, and instances where multiple opioids are prescribed to an individual.

Ensuring regular reviews

While pharmacists may be familiar with many of the common side effects of opioid medicines, the long-term adverse effects of opioid use may be less frequently rÂecognised and are often attributed to comorbid or newly diagnosed conditions (see Box). Certain effects (such as nausea and vomiting) may be short lived, but others are associated with longer term use (for example, sexual dysfunction). Effects may be dose-related, but it should not be assumed that effects noted at low doses are not induced by opioids[6]

,[7]

,[16]

.

Box: Adverse effects of opioid medicines (not exhaustive)

[6]

,[7]

,[16]

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Depression

- Drowsiness

- Changes in cognition

- Tolerance

- Dependence

- Misuse

- Lack of effect

- Driving impairment

- Opioid-induced hyperalgesia

- Sexual dysfunction

- Loss of libido

- Endocrine dysfunction

- Immune dysfunction

- Osteoporosis

- Increased risk of falls

- Risk of sudden death

- Kidney failure

- Liver failure

- Respiratory depression

With this in mind, any person prescribed opioids who presents with new symptoms should have their opioid use reviewed to see whether it may have contributed to the presentation of these symptoms. Trial and continual review of the benefits and risks of opioids is important; prescription should continue only if the person is benefiting by improvements to or maintainence of function in the mid-to-long term[1]

.

The coverage of opioids in the mainstream media has highlighted misuse and addiction as the most concerning outcomes of using opioids; however, there is currently limited evidence of this for prescribed opioids. A bigger problem lies in identifying people who are showing harm from their prescribed opioids, or when, despite a reasonable trial (of 3–4 months), there is limited functional improvement. In either case, reducing the medication is the safest option[16]

.

Pharmacists can help inform people about the benefits and the risks of using opioid medicines

At present, review of opioids is more likely to occur in general practice, where pharmacists are ideally placed to make changes, including reductions, that are made in agreement with patients. GP pharmacists are in an excellent position to assist with progress reviews and offer support. In the community, pharmacists can provide ongoing support and reinforcement for this process and may, in the future, continue the review and provide subsequent reductions.

Informing and involving patients

It can be difficult to talk about the changing risks and benefits of a prescription that was previously effective. For people living with pain, the idea of reducing ‘painkillers’ can be frightening and the change can feel out of their control. Pharmacists carrying out reviews must recognise these feelings and develop skills in person-centred consultation. Empathy with the person’s situation — and identification of the person’s values, beliefs and attitudes toward managing their situation — are important parts of shared decision-making, which should be supported by appropriate guidelines.

The Choosing Wisely campaign’s ‘BRAN’ initiative is a good guide on how to explore the pros and cons of the available treatments and management methods[19]

. This asks:

- What are the benefits?

- What are the risks?

- What are the alternatives?

- What if I do nothing?

Through person-centred consultations, pharmacist prescribers can help people who live with chronic pain to become better informed about the benefits and the risks of using opioid medicines, for any duration, at the start of treatment. Discussions should include the side effects that may be experienced, when and how the effectiveness of the opioid will be reviewed and how it will be tapered and stopped if that effect is not demonstrated; this approach reduces the chance of any harm occurring.

Get involved

Opioids may be helpful for some, but they have the potential to harm many others. Pharmacists are medicines experts who can deliver person-centred care. They have, or can develop, the knowledge and skills to support people to use opioids safely and effectively, and to review and reduce opioids when they are not delivering benefit.

People who reduce opioids after years of use have described the experience as ‘waking up’[20]

. Now, we must wake up as a profession and demonstrate leadership in opioid management.

- This article was amended on 23 November 2018 to correct the volumes of buprenorphine and tapantanol at 70mg and 80mg morphone, respectively.

Emma Davies is advanced pharmacist practitioner in pain management at Abertawe Bro Morgannwy University Health Board

Nina Barnett is consultant pharmacist at London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust and NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service

References

[1] Shapiro H. Opioid painkiller dependency (OPD): an overview. A report written for the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Prescribed Medicine Dependency. 2015. Available at: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/25398/ (accessed November 2018)

[2] Davies E, Phillips C, Rance J & Sewell B. Examining patterns in opioid prescribing for non-cancer-related pain in Wales: preliminary data from a retrospective cross-sectional study using large datasets. Br J Pain 2018; in press. doi: 10.1177/2049463718800737

[3] Mordecai L, Reynolds C, Donaldson LJ, & de C Williams, AC. Patterns of regional variation of opioid prescribing in primary care in England: a retrospective observational study. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68(668):e225–e233. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X695057

[4] Stannard C. Opioids in the UK: what’s the problem? BMJ 2013;347(7922):f5108. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5108

[5] Els C, Jackson TD, Kunyk D et al. Adverse events associated with medium- and long-term use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;10(10):CD012509. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012509.pub2

[6] Seyfried O & Hester J. Opioids and endocrine dysfunction. Br J Pain 2012;6(1):17–24. doi: 10.1177/2049463712438299

[7] Mazereeuw G, Sullivan MD & Juurlink DN. Depression in chronic pain: might opioids be responsible? Pain 2018;159(11):2142–2145. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001305

[8] White House. Health Factsheet: President Donald J. Trump is taking action on drug addiction and the opioid crisis. 2017. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trump-taking-action-drug-addiction-opioid-crisis (accessed November 2018)

[9] Niv D & Devor M. Chronic pain as a disease in its own right. Pain Pract 2004;4(3):179–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2004.04301.x

[10] Price C, Hoggart B, Olukoga O et al. National pain audit — final report 2010–2012. 2012. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/members_articles_npa_2012_1.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[11] Finestone HM, Juurlink DN, Power B et al. Opioid prescribing is a surrogate for inadequate pain management resources. Can Fam Physician 2016;62(6):465–468. PMID: 27302997

[12] Gordon K, Rice H, Allcock N et al. Barriers to self-management of chronic pain in primary care: a qualitative focus group study. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67(656):e209–e217. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X688825

[13] Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford RM et al. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open 2016;6(6):e010364. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010364

[14] British Pain Society. The silent epidemic — chronic pain in the UK. 2016. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/mediacentre/news/the-silent-epidemic-chronic-pain-in-the-uk (accessed November 2018)

[15] Stannard CF. Pain and pain prescribing: what is in a number? Br J Anaesth 2018;120(6):1147–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.03.002

[16] Royal College of Anaesthetists Faculty of Pain Medicine. Opioids Aware: A resource for patients and healthcare professionals to support prescribing of opioid medicines for pain. 2015. Available at: https://www.fpm.ac.uk/faculty-of-pain-medicine/opioids-aware (accessed November 2018)

[17] Rennick A, Atkinson T, Cimino NM et al. Variability in opioid equivalence calculations. Pain Med 2016;17(5):892–898. doi: 10.1111/pme.12920

[18] Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada. Sink or swim? Helping patients and practitioners to understand opioid potencies and overdose risk. 2017. Available at: https://www.ismp-canada.org/download/safetyBulletins/2017/ISMPCSB2017-08-UnderstandOpioids.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[19] Choosing Wisely UK. About Choosing Wisely UK. 2016. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.co.uk/ (accessed November 2018)

[20] Underwood C. ‘They wake up out of a fog’: Opioid taper program helps chronic pain patients wean off powerful drugs. 2018. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/amp/1.4747716 (accessed November 2018)