PA Images

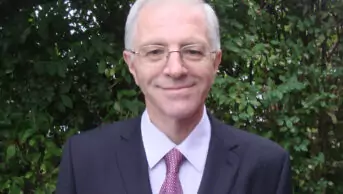

Jean Lindenmann, a Swiss scientist who discovered interferon with British colleague Alick Isaacs at the age of 32, has died of cancer aged 90.

The pair made their discovery in 1957 at the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) in Mill Hill, London, where Lindenmann had arrived in 1956 on a year’s fellowship from the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. Attracted by the need to learn English and greater opportunities than those offered in Switzerland where he found medical microbiology “ossified”, Lindenmann first started work on the polio virus but that project proved unsuccessful.

He was introduced to Isaacs, head of the World Influenza Centre, situated in the next door laboratory to Lindenmann’s, and they discovered a common interest in the phenomenon of viral interference. By March 1957, they had established that a protein produced by embryonic chick cells, previously exposed to heat-inactivated influenza virus, could inhibit replication of live influenza virus. The protein was named interferon because it interfered with viral replication.

“Jean, I believe, suggested the name interferon,” says Derek Burke, former professor of biological sciences at Warwick University, who was working at NIMR at the same time as Lindenmann. “But that didn’t stop Lord Hailsham, chairman of the Medical Research Council (MRC) at the time objecting that it was a nasty hybrid word with both Latin and Greek roots.”

Burke remembers Lindenmann as rather shy, quiet and stolid, with a great capacity for hard work — a good foil to Isaacs who “fizzed with brilliance, talked non-stop and sang opera challenging us to identify the works”.

“1957 was a very special summer and I shall always remember Alick, Jean and I doing haemagglutination titrations in room 215,” he says.

Lindenmann returned to Zurich University in summer 1957 and did not pursue what he knew to be the next step — the purification and structural analysis of interferon. He believed that would be best done by biochemists.

He turned his attention to why inbred laboratory mice were resistant to influenza viruses that killed other strains of mice. And he found interferon played a part.

“The sad truth is that it took me the better part of two decades to find out that genetically determined resistance to influenza virus, my main preoccupation during all those years, was interferon-related,” he wrote in 1981.

Charles Weissmann, of the Institute of Molecular Life Sciences at Zurich University, was a medical student when he first met Lindenmann in 1955, when he was supervising a biology course at the university. A friendship developed and Weissmann was struck by the reticence of this “outstanding scientist and human being”.

“Modest and unassuming, he kept out of the limelight to which many another with his accomplishments would have striven,” he said. Lindenmann had not only laid the foundations of a new field of research, but lived to see its successful evolution, he said.

Lindenmann was born in Zagreb and graduated from medical school in Zurich in 1951 and then did four years post-doctoral work at the city’s Institute of Hygiene, where he also worked between 1957 and 1959. He spent two years (1960–1962) in Bern at the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health and was then appointed visiting assistant professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. In 1964, he returned to Zurich University where he spent the rest of his career. He retired in 1992.

He is survived by his sons, Jean-Michel and Christian. His wife Ellen Buechler, who he married in 1957, died in 2007.

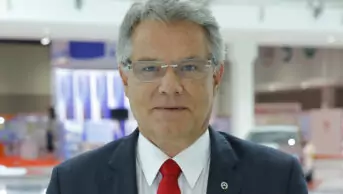

Toine Pieters, author of ‘Interferon: the science and selling of a miracle drug’, published in 2008, believes that early success may have cast a shadow on Lindenmann’s subsequent career. “Lindenmann started his career with a rocket-star performance that would hamper the rest of his life: the discovery of a billion dollar molecule, interferon,” said Pieters, of the Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences, the Netherlands. “He would never match the early productive days at MRC with Alick Isaacs. But he was a most generous and friendly person who shared all his archives and letters with myself in the early 1990s.” In his later years, Lindenmann became increasingly interested in the history and philosophy of science, Pieters added.

Writing in Nature in 1998, Lindenmann said the fate of interferon illustrated how the style of biomedical research had changed drastically over the previous 40 years. “Beginning as a rather esoteric laboratory phenomenon (some would say laboratory artefact), it passed through a sort of cottage industry to end up as part of the metropolis of modern biotechnology.”

You may also be interested in

Nina Barnett (1965–2023)

Dominique Jordan (1960–2023)