Charles Shearn

Dame Sally Davies, chief medical officer for England and chief medical advisor to the UK government, is well known for issuing stark warnings on the careless use of antibiotics. But can pharmacists play a role in protecting the drugs for the future? Here,The Pharmaceutical Journal and Gino Martini, new chief scientist at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), meet with Davies, who weighs in on pharmacists’ centrality to reducing medications errors; pharmacist independent prescribing; and pharmacy’s potential for delivering C-reactive protein testing — a point-of-care diagnostic to support antibiotic prescribing decisions, which could help stem the tide of antimicrobial resistance.

In late February, you co-hosted a Facebook Live session with health and social care secretary Jeremy Hunt on medications errors, soon after he announced a need for action on the issue. What needs to be done to reduce medication errors and can pharmacists play a role here?

Clearly, pharmacists are essential to this. In my own experience as a clinician in a hospital, pharmacists were so helpful when patients went down to pick up their prescriptions; in checking interactions of drugs; and checking that I was using the antibiotics that were actually on our local formulary — depending on the bacteria and antibiotic profiles. Pharmacists on the ward rounds could also advise and check with people in training that they moderated the doses depending on the blood results.

Pharmacists are doing revÂiews of medicines in care homes, and in older people in general practice. It is impressive how they reduce polypharmacy to get the best outcome and the fewest side effects.

Pharmacists are central to our system, and for making it safer. I’m told there are more than a billion prescription items dispensed every year; we know that there are very few dispensing errors, and that must mean that in the past you were good at reading, because doctors don’t have good writing! Electronic prescribing makes this easier, of course, but I think that few errors are a testimony to pharmacy’s professional approach.

We want to increase the reporting of errors so that we can all learn from them. As you may know, the government is putting in place some legislation to improve reporting by removing barriers and protecting pharmacy professionals who work in registered pharmacies. This is all about supporting pharmacists to do a better job because we all understand that you’re not going to be able — whatever your profession — to be as open as you want to be if you’re fearful that you will incriminate yourself. The legislation is a good move. Then we’re going to move onto looking at how we can support pharmacists working in hospitals, too. We need more data to know what’s going on; we need data to make sure it’s all linked up and that we do it properly; and we need to accelerate and support pharmacists to roll out electronic prescribing.

I suppose that this is the moment that I say thank you to the RPS for the resources you produce for the profession, including the

British National Formulary

, because we all know they are high quality, they’re evidence based, and they make a difference.

“I wonder if community pharmacists will do first-line C-reactive protein testing in the future. I’d love to see it in the pharmacy, actually”

As well as reducing risk of harm to patients, can community pharmacists also act as patients’ first port of call to relieve the burden on GPs, or even work in general practice?

Well, I want patients to get the best service they can and, clearly, not all of them need to go to the GP. You can seek advice using the internet, apps like Babylon, or NHS 111. For other ailments — coughs, colds, moderate or mild flu — the pharmacy is the ideal place to go for good advice.

I was in the queue at a pharmacy the other day, because I was picking something up for my husband, and I overheard the pharmacist giving some really good advice — which is just what we need going forward — this interplay of receiving first-line advice for mild conditions, where, in general, you don’t need antibiotics, and if you do need them, being pointed there. Indeed, I wonder whether pharmacists, over time, will be drawn into doing some of those first-line tests, like C-reactive protein, so that you can say, “well, your C-reactive protein looks all right, so you really don’t need to talk to your GP,” and stand even prouder as part of the clinical team that makes patients better. I’d love to see it in the pharmacy, actually. I think there are diagnostic tests for which it would be really useful to back up your clinical judgement. If I’m sitting with a patient in a room and there’s no one else around, I can ask them in-depth questions. I can examine them. You can’t always do that as easily in community pharmacy, so it would be great to do some of the simple tests and screen patients so that you can give them the right advice more easily. I think this is a development that we can explore.

I know that the government have been using the Pharmacy Integration Fund to try and increase the number of pharmacists embedded in GP practices to 2,000 by 2020. I think that’s great. And as I said before, pharmacists are clinicians and they should be part of the clinical team, and bring something different. We don’t have many clinical pharmacologists in Britain now, and although prescribing improved with the General Medical Council doing their prescribing tests, and with people having to go back and learn it if they don’t know enough, pharmacists are the experts. You’re trained in it. We need to harness that expertise in the interests of patients. I’m very supportive of that.

Doctors have sometimes been said to be protective of their prescribing powers — how do you feel about pharmacists taking on extended roles, such as prescribing?

Clearly, pharmacists know what they’re doing with drugs — often better than doctors — so the question is, where is it helpful to prescribe? It is helpful to prescribe for flus, coughs, colds, and simple pain relief. If you get into where antibiotics are needed, I think there’s some real training required to make sure that you’ve got the right diagnosis and the right antibiotic. Not one standard set of training because, of course, the resistance profile of the bacteria will be different in one part of the country to another part. So I think that it’s going to be more difficult to do antibiotic prescribing. I don’t rule it out, but we’d need to think carefully about how you make sure you’ve thought through that the patient doesn’t need to see a doctor, because there may be incipient sepsis, or something like that. And I think there are other specialist areas where I would want to explore quite carefully what training was needed and whether it would work. But I am very content with simple everyday illness being looked after, advised on and prescribed for by pharmacists.

Although, I’ve been wondering about whether you can have pharmacies that are the experts in prescribing antibiotics. I’ve floated a new idea for you. And after you’ve left everyone will say: “We didn’t know you were wondering about that!”

Source: Charles Shearn / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Recent research funded by Public Health England suggests that more than a fifth of antibiotic prescribing in primary care could still be inappropriate. Are campaigns to reduce the prescription of antibiotics without clinical need working?

I think we’re getting the message across in this country, but it always takes time. This is a behavioural thing. We’ve got evidence that patients feel validated in their illness if they’re given an antibiotic. They ring up work and say: “Hey, I really am ill — I’ve got an antibiotic,” so we have to look at the whole picture, not just at the education of patients and the clinicians who are looking after them. We have to look at behavioural issues, and, actually, we picked up an important one while preparing an antibiotic overuse campaign that went out as a pilot in autumn last year in the North West, and then across England over the winter. We have to look at people’s perceptions. We found that if patients were told an antibiotic was not needed, they thought doctors and nurses were trying to save money. So that campaign — and you may have seen it, the antibiotics dancing and singing — aimed to change those behavioural connections. So it’s not saving money. It’s actually: “If I don’t look after them, they may not be there for me in the future.”

Behaviour is so terribly important to understand. And having mentioned the validation of being ill, there is a prescription sheet ‘Treating your infection’ from Public Health England that can be given to people who do not need antibiotics. This ‘prescription’ acknowledges that you have got an illness, but that it doesn’t need antibiotics. This is a way of addressing the validation issue and giving advice, because we all know that when people go to the doctor they don’t always remember the discussion very well. There they are with the advice in their hands and they can go back to it. I thought this was a nice way of doing it.

This is a complex area, but we are making strides. I’ve got the data here, and I think it’s really good data. In primary care, antibiotic prescribing decreased by 11% from 2014 to 2017 — more than 4 million fewer antibiotic items dispensed. And community pharmacists played a massive role in making that happen.

The secondary-care prescribing story is a bit different; antibiotic prescribing still continues to increase, although the increases are smaller. But we’ve reduced use of last-resort antibiotics (piperacillin/tazobactam and carbapenems) by 4% from 2015 to 2016. And importantly in hospitals, 88% — which is good, but I want 98% — of antibiotic prescriptions were reviewed at 24–72 hours, so that’s really good. It’s just about making sure that people started on antibiotics are receiving the right treatments.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has been a big theme of your tenure — in the past, you made headlines for describing the future as a “post-antibiotic apocalypse”. Do you get frustrated that people are not ‘up in arms’ about it and are just letting it pass?

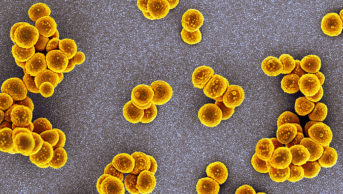

I think we’ve made great progress. I started on this campaign in March 2013, and at that point people were saying: “What are you talking about? Oh, does it matter?” Now, not a week goes by without something about drug-resistant infections, antibiotic overuse, and even the “antibiotic apocalypse”, so I think we’re making great progress, but we haven’t embedded it in beliefs and behaviours yet, so there’s a long way to go. I’ve told you how we are bringing use down, but, worryingly — take Escherichia coli, a common bloodstream infection, usually acquired from our own microbiome — four in ten patients with E. coli septicaemia can’t be treated with common antibiotics. So we are moving into an area where people are suffering, and if you have a drug-resistant infection that takes you into hospital, it doubles hospital stays, it doubles mortality, and it doubles the cost. So, yes, everyone’s losing. But the one I care most about is the patient.

“Demographics and demands are changing, but the NHS will still be there”

Are there models of care being used abroad that you think could be adopted in the NHS?

I think we can always learn from other countries. The ones that spring to mind are Japan for social care and older people, and then Scandinavian countries — if you look at their use of antibiotics, it’s very low. If you look at the data they give about lots of things, it’s because they have these great patient registries. There must be things to learn from those countries. And Cuba, which is fantastic on preventive medicine, their vaccination programmes, their screening programmes — really interesting.

There’s this big push globally on universal health coverage, and we are the first system to truly provide universal health coverage, where it’s available to everyone, and where no one is out of pocket if they are seriously ill. I mean, I’ve given my life to the NHS. I care about it. I think it’s fantastic.

Source: Charles Shearn / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Which technological advancements do you think will have the biggest impact on the NHS in the next few years?

Well, I think it will be digital. Using apps to drive better care will take us into biomarkers. Our phones are already collecting a lot of basic data about us and they can collect far more. I think that apps are the way we’re going to go with medicine, in a big way. But we’ve got to make sure that we have high-quality apps and that we don’t have an increasing divide of inequality. They’ve got to be for our public, not just for those who are rich and choose to pay for them.

And we’ll move into artificial intelligence — there’s a vast amount that we can do with artificial intelligence, but we must check that it works with clinicians for patients. Microsoft made an artificially intelligent bot who had online conversations through Twitter, and it became foul-mouthed within 24 hours! Really awful. It shows you the problems with artificial intelligence. It’s educated by what you show it, so we will have to take that forward very steadily. And of course, I can’t not mention genomics, which is going to play a big role.

July 2018 marks the NHS’ 70th birthday — do you think it will still be around in another 70 years?

Oh, absolutely. It’s become our national religion. It will change, and it has to change. The demographics are shifting, and demands are changing, but it will be there.