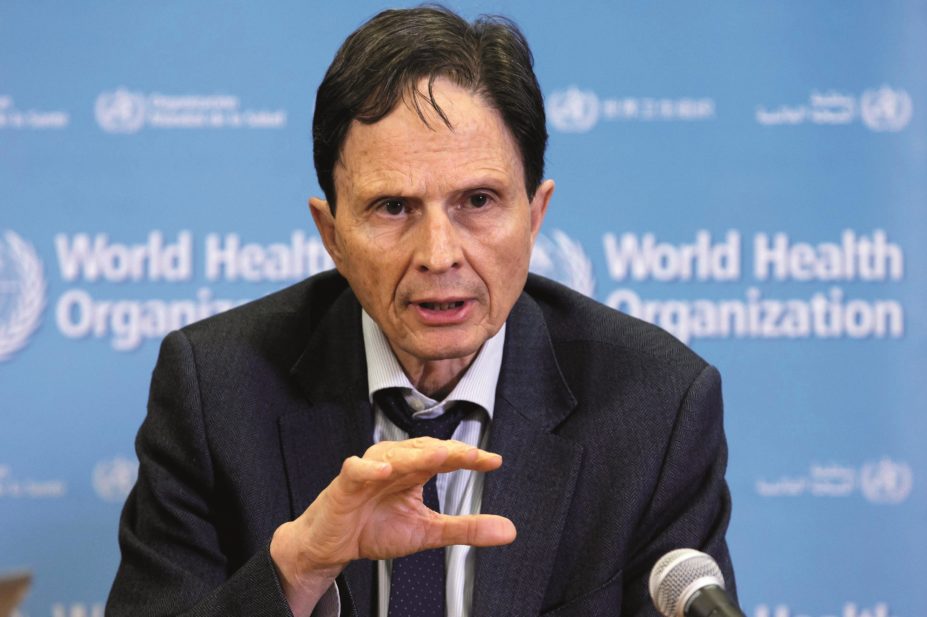

epa european pressphoto agency b.v. / Alamy Stock Photo

David Heymann is chair of the International Health Regulations emergency committee. He is also professor of infectious disease epidemiology at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the head of the Centre on Global Health Security at Chatham House, London, and chairman of Public Health England. Previously he was the World Health Organization (WHO) assistant director general for health security and environment, and representative of the director general for polio eradication.

From 1998 to 2003, he was executive director of the WHO communicable diseases cluster, during which he headed the successful global response to severe acute respiratory syndrome and, before that, was director for the WHO programme on emerging and other communicable diseases.

Before joining the WHO, he worked for 13 years as a medical epidemiologist in sub-Saharan Africa, on assignment from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where he participated in the first and second outbreaks of Ebola haemorrhagic fever, and supported ministries of health in research aimed at better control of malaria, measles, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases.

On 1 February 2016 WHO director general Margaret Chan declared that the recent cluster of microcephaly cases and other neurological disorders reported in Brazil, following a similar cluster in French Polynesia in 2014, constitutes a public health emergency of international concern.

What are your aims now that a public health emergency has been called for microcephaly?

Because the public health emergency was called for the microcephaly instead of the Zika virus, we can do better surveillance and understand which countries that have a Zika outbreak also have microcephaly and other disorders. This requires a standardised case definition and collaborative efforts to determine whether or not there is a link between the microcephaly and the virus.

Is this more a precautionary health emergency compared with earlier ones we have seen such as Ebola or H1N1?

I would like to say it is an emergency because there is so much that we do not understand right now. First of all, it is not even clear whether or not there are clusters of microcephaly or whether they’re using a right gauged definition throughout the world. And those are the things that are being examined right now by the WHO.

Zika is a virus like dengue or chikungunya, and they require vector control

The precautionary measures are for Zika because it’s a virus like dengue or chikungunya, and they require vector control [any method to limit or eradicate the mammals, birds, insects or other arthropods — vectors — which transmit disease pathogens]. We need to understand how infection occurs in order to prevent it from happening, and we need to consider whether a vaccine could be developed. So the precautionary measures are on the virus, whereas the urgency and emergency measures are on the microcephaly.

Is the increase in Guillain-Barre syndrome cases, which can cause paralysis and death, also of concern?

Guillain-Barre is a rare but serious event, and it can happen when there’s a reaction to antibiotics, a vaccine or a viral infection. So, if there’s an increase of these cases, then there’s a different reaction to Zika compared with other viruses. But this has to be verified by standardised surveillance and that’s the appeal for standardised surveillance and research — to determine whether or not there’s a link.

The WHO has said that up to 4 million people could be infected with Zika in the Americas, of which 1.5 million alone will be in Brazil. What about the rest of the world? Are they also at risk?

The virus is already known to circulate in Africa and in Asia. It is known to have been in India also. Now it has made it to Latin America. So really it has just been travelling around the world.

Will disease surveillance be essential here?

Yes, we need to be looking to see if there are clusters of microcephaly that are occurring where Zika outbreaks occur. But you have to wait nine months after the outbreak to determine the link.

How far off are we from an effective vaccine, given there is no effective vaccine against Dengue, which the same vector — the yellow fever mosquito — spread?

It’s not clear how far off we are from a vaccine. But there first has to be basic research to develop the strains that go into a vaccine. Then it has to be tested in the animal model and, if it has been shown to be safe and effective in an animal, then it goes into safety and effectiveness studies in humans. So, we’re probably talking about years after the initial development is done.

Do we know which bodily fluids the virus is present in?

There have been reported cases of sexual transmission and also through blood transfusion. There will be further examinations in all these cases. Hopefully, the WHO will be able to coordinate, which should give an idea of where the risks are.

Do we know how the virus causes the characteristic symptoms of the disease?

In more than 80% of cases, the disease is very mild and causes few symptoms (e.g. fever, rash). But again, there’s not a lot of experience with it because it is so benign to human health.

Do we know by what mechanisms the Zika virus could cause congenital malformations and neurological abnormalities?

No, and it is important to stress that we don’t even know if it does it yet. Therefore, we could not possibly postulate how. First of all, there has to be a causal link between the two, which incidentally, there has been in a virus identified in a few specimens from children with microcephaly. But that’s not confirmation, just coincidental. We call this circumstantial evidence, but it’s not proof.

We don’t even know if the Zika virus definitely causes congenital malformations

Do you think you will need to rally resources like we saw in the Ebola outbreak?

In this case, different types of resources have to be mobilised compared with Ebola. We need money to take care of vector control, and we need money for research to determine whether or not there’s a linkage between the virus and microcephaly.

Is there any research to see if this virus is mutating?

There are genetic studies happening. I would be looking for a change in the structure of the genome to see if there were changes. Those changes might be the cause of the change in virulence and if indeed there is a link between Zika and microcephaly.