This content was published in 2004. We do not recommend that you make any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Scotland’s pharmacy plan “The right medicine: a strategy for pharmaceutical care in Scotland” called for proactive developments in pharmaceutical care of patients. It highlighted areas where high quality work had been achieved and suggested other areas where work had still to be done in the modernisation of pharmacy services.1 Pre-admission clinics were described in the document as representing an area where pharmaceutical care had not really been explored. The pharmacist’s role at pre-admission clinics has been described previously and these reports formed the basis for the pre-admission pharmacist’s activities as described below.2–5

An opportunity for change

At Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, pre-admission clinics are run within the ear, nose and throat, maxillofacial, urology and ophthalmology departments. ENT was chosen as the first department to introduce the service since the pre-admission clinic was established, had dedicated nursing staff and reliable patient numbers. Patients are invited to attend one to two weeks before their theatre date and have all the necessary pre-operative tests carried out. They are also admitted by a nurse and clerked by a member of the junior medical staff. Following criteria agreed by the anaesthetic department a decision can be made as to whether the patient can be admitted to hospital the day before or the morning of their operation.

Following a literature search and tele phone enquiries to all hospital pharmacy departments in Scotland to gauge current practice, standard operating procedures were drafted for services to be carried out at the clinic. The pharmacist’s role involves:

- Taking a detailed medication history, with specifically created documentation to be filed in the medical notes

- Checking patients’ own drugs for use in hospital

- Writing the inpatient medication chart

- Counselling patients on current medication and post-operative therapy

- Communication with primary care health professionals if appropriate

- Advice to medical staff on administration of medicines during the peri-operative period

- Writing discharge prescriptions and organising supplies for inpatient stay and discharge

- General health promotion

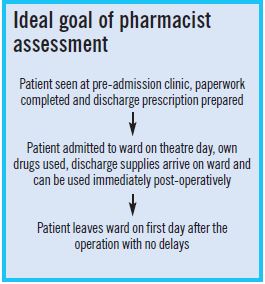

It was envisaged that the pharmacist would see patients after nursing staff had made their assessment but before the doctor had seen them. This would mean that medical staff have access to a detailed medication history and would allow them to check and sign the inpatient medication chart and discharge prescription in preparation for admission. One year on, this arrangement has continued, since it is a natural progression to a final assessment by the doctor.

Current practice

Medication history

It has been documented in the literature that pharmacists are the most effective health care professional to take an accurate medication history.6 A standard operating procedure was written and a form devised and piloted to allow documentation of the history. This includes prescription and over the-counter remedies, including herbal and homoeopathic preparations, and any drug allergies or adverse drug reactions. The finalised form has now been printed in trust format and serves as a reference in the medical notes.

Checking patients’ own drugs

The letter inviting patients to attend the clinic was amended to ask them to bring in all their medicines, including over-the-counter remedies. This allows the pharmacist to check patients’ own drugs and obtain consent for their use, thus reducing waste and the need for large stock lists on surgical wards. At the clinic, patients are given a medicines management leaflet to reinforce the reasons why their own medicines are used in hospital.

Writing the inpatient medication chart

The patient’s usual medicines can be written on the inpatient medication chart in preparation for admission. A symptomatic relief policy (allowing nurses to treat minor ailments with Mucogel, senna, Strepsils, peppermint water, paracetamol, glycerin suppositories and simple linctus) operates within the hospital and this can also be written up with any relevant exceptions. The doctor then checks and signs the medication chart at the pre-admission clinic. Before a pharmacist was present at the clinic problems such as incomplete prescriptions, omissions, inappropriate prescribing and errors were encountered.

Counselling patients

The opportunity can be taken at this time to counsel patients on their current therapy. For example, confirmation of inhaler operation, reinforcing advice on timing of doses and meals, etc. Our experience is that patients often feel that they can ask more questions in a relaxed one-to-one conversation with the pharmacist. The pharmacist then explains to patients what medicines they can expect to use after the operation and on discharge. A guide to standard post-operative medication was written in partnership with the ENT consultants. This information is rein forced with patient information leaflets and again on the ward on admission to hospital.

Communication with primary care

Pharmacists in pre-admission clinics are in an ideal setting to assess the pharmaceutical care needs of patients. The surgical team managing the patient during admission may not address interventions that the pharmacist believes are necessary for ongoing medical problems. A pharmacy referral form in Grampian allows any issues regarding current therapy to be referred to the patient’s GP, practice pharmacist, nurse or community pharmacist.

Administration of medicines during the peri-operative period

A protocol has been written which is used by the pharmacist at the pre-admission clinic to advise the medical staff and the patient on administration of medicines during the peri-operative period. This ensures patients receive all usual therapies unless contraindicated during this time. Important advice can be given regarding stopping any medicines before surgery, therefore preventing patients from having their surgery cancelled at the last minute, eg, warfarin and clopidogrel. In time, this will be used as a ward-based reference source for nursing staff administering medicines to patients who are fasting for theatre.

Writing discharge prescriptions

Discharge prescriptions are prepared by the pharmacist at the pre-admission clinic and are checked and signed by the doctor. Standardised regimens of post-operative medication have been agreed with the ENT surgeons, following an audit of the discharge prescriptions from the ward over a three month period. he prescriptions may be for warded to the hospital pharmacy where they are dispensed on the day of surgery. This means:

- The patient receives the right medicine, at the right time and in the appropriate form

- The supply is labelled for discharge so appropriate courses of medication, eg, antibiotics, are assured

- Patients do not need to wait for medicines at the time of discharge, increasing patient satisfaction

- Beds are managed more efficiently because the discharge process runs more smoothly

- There is less drug waste

At any point during the admission, medical staff are free to add any appropriate medication and can order supplies through the normal procedures. In some instances, dis charge prescriptions are held in the notes to be confirmed after the operation.

Audit and evaluation

There are numerous areas of this development that could be used as audit points. An assessment could be made as to the perceived advantage of a pharmacist at the pre admission clinic by way of a satisfaction questionnaire to both patients and staff. An assessment could be made of the interventions carried out affecting the time of patients’ admissions, administration of medicines, etc. The accuracy of transcribing could be compared with with that of the medication charts written by medical staff for patients who have not attended the pre-admission clinic and are clerked on the ward.

The impact of the protocol for administration of medicines during the peri-operative period could be measured by first assessing nurses’ opinions and practice as to the medicines given to patients while fasting and then reassessing after the protocol is released and training has been given. The impact of pharmacists writing the discharge prescriptions could be assessed using various tools, eg, waiting time of patients, number of items added post-operatively and costs after standardisation.

Conclusion

The introduction of a pharmacist to the pre admission clinic has been a rewarding task mainly due to the enthusiasm of the staff involved. Work will continue to expand the peri-operative medication protocol and train nursing staff in its use. Audit work will be carried out to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of this role and we aim to extend it to other surgical specialties.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to our colleagues within the pharmacy department for their support for this new role. Also special thanks to Susan Healy, principal pharmacist, Susan Davidson, senior clinical pharmacist and Sheila Wheeler, senior staff nurse, whose enthusiasm and support were invaluable.

References

- Scottish Executive. The right medicine: a strategy for pharmaceutical care in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive; 2002.

- Jay C. The role of the pre-admissions pharmacist. Hospital Pharmacist 1998;5:105–6.

- Hebron B, Jay C. Pharmaceutical care for patients undergoing elective ENT surgery. The Pharmaceutical Journal 1998;260:65–6.

- Hick H, Deady P, Wright D. The impact of the pharmacist on an elective general surgery pre-admission clinic. Pharmacy World and Science 2001;23:65–9.

- Shah R. Medicines management in elective surgery patients. Hospital Pharmacist 2000;7:73–8.

- Higham C. Drug history taking — a role for the ward pharmacist. The Pharmaceutical Journal 1987;228:302–5.