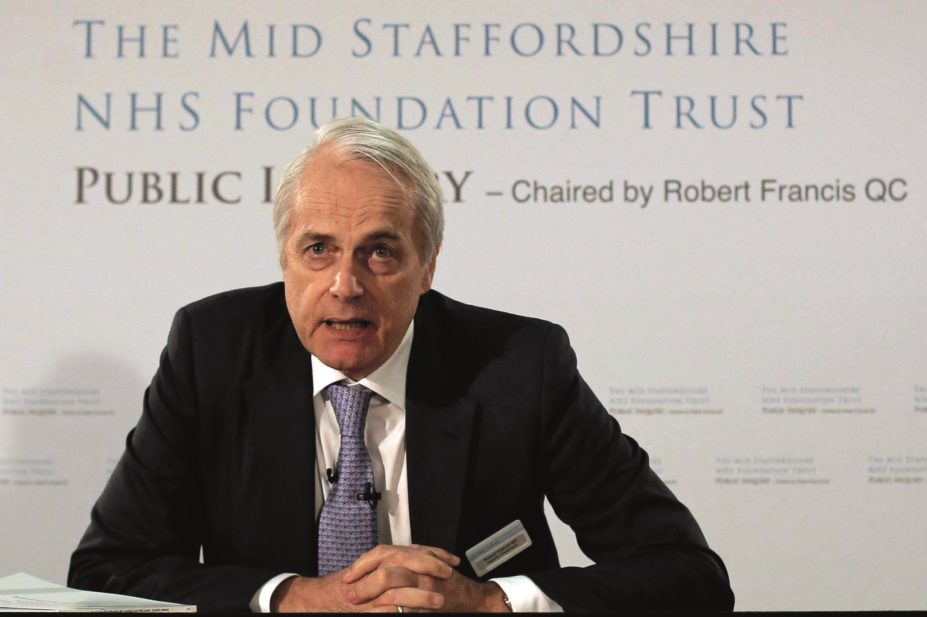

epa european pressphoto agency b.v. / Alamy

NHS organisations should appoint whistleblowing guardians to support staff who have concerns about poor care and staff who whistleblow should have more protection from recrimination, a report[1]

by Sir Robert Francis says.

Francis, who led two inquiries into the care scandal at Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust between 2009 and 2013, published his ‘Freedom to speak up’ review on 11 February 2015. The report sets out 20 principles to create a “more open and honest” reporting culture within the NHS and to provide better support to whistleblowers.

More than 19,500 NHS staff replied to a survey to inform the report and Francis met more than 300 people, including whistleblowers, and took into account written evidence from over 600 NHS staff and 43 organisations. From this evidence he learned that many staff who had tried to speak up about poor care had been bullied and silenced by managers, and some of those who had refused to be silenced had lost their jobs and often found it difficult to find other work.

His report recommends that NHS trusts and other NHS organisations appoint ‘freedom to speak up guardians’, so that staff raising concerns have somewhere to go for independent advice, and a national whistleblowing tsar to support guardians and intervene when things go wrong. Staff should receive better training to help encourage them to speak up about safety risks and prevent bullying of those who do, it adds.

Francis calls for a government review of legislation on discrimination, so that staff who lose their jobs because of whistleblowing do not suffer prejudice when they seek new work. A support scheme for staff who experience difficulty finding employment as a consequence of whistleblowing is also needed, he adds.

Health secretary Jeremy Hunt has accepted all the recommendations in principle and will consult on a package of measures to implement them.

Francis emphasises that the principles in his report should apply to staff working in primary care, including community pharmacy, and acknowledges that such staff can feel particularly isolated. Primary care staff are far more likely to take their concerns outside of their organisation, he points out, but “the demise of primary care trusts” leaves it unclear where they can go.

The staff survey conducted to inform the report highlights just how concerned pharmacists are about whistleblowing issues. Of the 4,500 respondents from primary care, 68% worked in pharmacy and just 19% in general practice.

David Branford, chairman of the English Pharmacy Board at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, suspects that pharmacists are at greater risk of being bullied than other healthcare staff and may find it more difficult to whistleblow. “Firstly, most pharmacists work in isolation. Even if a pharmacist is part of a clinical team they are often the sole pharmacist in that team,” he says. “Secondly, many pharmacists work as locums and the report specifically highlights locums as a vulnerable group.”

He also highlights the importance for pharmacists of a good working relationship with fellow team members. “The ability to be an effective pharmacist depends on that collaboration, whether it is with a GP surgery, a care home or on a ward,” Branford says. “If those persons adopt an antagonistic approach to the pharmacist, or even worse have control over their future employment or livelihood, it takes a really brave person to whistleblow.”

However, he points out that it is vital that pharmacists are enabled to speak up because medicines can be used as a form of control of patients and pharmacists could become aware of circumstances where medicines are being used in an abusive or inappropriate way.

“Every pharmacist should read the report and reflect on their workplace environments,” Branford says. “It provides a large number of recommendations that if followed by organisations would transform the workplace.”

Dave Thornton, president of the Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists (GHP), says the GHP supports the principles within the report, particularly around the culture of safety and raising concerns. “All staff who feel the need to speak up about something within the NHS should know how to do this, be supported in the process and be free from bullying as a consequence of a concern they have raised,” he says.

Cathy James, chief executive of Public Concern at Work, highlights the health sector as unusual. “Evidence demonstrates that whistleblowing concerns raised in the health sector remain under protracted investigations that yield fewer resolutions with more whistleblowers subjected to formal sanctions than in other sectors,” she says.

References

[1] Francis R. Freedom to speak up – An independent review into creating an open and honest reporting culture in the NHS. 2015.

You may also be interested in

NHS Tayside pharmacists felt ‘professionally vulnerable’ drug dosing concerns were ignored

Medicines shortages and slow approvals put ‘significant burden’ on pharmacists, says report