Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the circumstances in which patients requested antivirals for swine influenza during the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009. To assess severity and duration of symptoms, compliance, side effects, patient perceptions and treatment effectiveness.

Design

A quantitative and descriptive, cross-sectional study.

Subjects and setting

Patients who had received an antiviral at one of the antiviral collection points within NHS North Lancashire boundaries during the months of August and September 2009.

Results

The antivirals were only effective at reducing the duration of illness if given in the first 48 hours of symptoms. A mean reduction of 1.2 days of illness was seen in patients who received the antiviral during the first 48 hours of symptoms. There was no evidence to suggest that the antivirals reduced the severity of symptoms. Compliance was relatively high with 86 per cent of patients completing their course of medication; however a total of only 31.5 per cent of patients received their medicines in the first 48 hours and completed the course of treatment. Of the patients who received their medicines after the first 48 hours of illness, 82 per cent still believed that the antivirals helped their recovery even though there is no evidence to suggest they did.

Conclusions

During a pandemic there should be a clear message to the public that the earlier antiviral medication is started the better and that medication has little benefit if given after 48 hours of illness. Measures should be put into place to ensure patients access antivirals promptly during any future pandemic. What the public needs to do to avoid spread of the disease should be widely publicised, including the need to stay at home and not to return to work until symptoms are no longer present.

Swine influenza is a respiratory illness caused by the type A influenza (H1N1) virus. The influenza pandemic that affected many countries around the world in 2009 was caused by a new strain of the virus named Pandemic H1N1 2009 by the World Health Organization. On 11 June 2009, the WHO declared a pandemic as a result of ongoing community level outbreaks of swine influenza in many parts of the world.

The UK strategy during the initial containment phase of the pandemic, when numbers reported were relatively low, was to organise laboratory testing of throat swabs taken from symptomatic patients. If the test result was positive the patient was offered antiviral medication, which was distributed via the Health Protection Agency. The antiviral of choice was oseltamivir; zanamivir was reserved for those not able to take the first-line antiviral due to contraindications.

Contact tracing and prophylaxis measures were carried out in an attempt to reduce the spread of the virus. The Department of Health (DoH) issued guidance to doctors to ensure that those at higher risk of developing disease complications received priority access to antivirals within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms. High-risk patients included those with chronic lung, kidney or heart disease, the under-fives, the over-65s and pregnant women.

As the number of cases increased in the UK, the health secretary announced on 2 July 2009 the NHS had moved to a “treatment for all” phase: people were treated based on their symptoms and contact tracing and subsequent prophylactic treatment ceased.

Primary care organisations had already begun to establish antiviral collection points and patients’ “flu friends” were presenting at these collection points with authorisation vouchers for antivirals issued by GPs.

An influenza friend is a representative of a symptomatic patient who collects antivirals on their behalf. The friend may be a family member, a friend, a carer or a trusted person allocated by the primary care organisation.

Authorisation vouchers were developed by the DoH to assist prescribing and issuing procedures. Patients were not required to pay for the antiviral medicines.

To alleviate the pressure on GPs the National Pandemic Flu Service was launched in July 2009 to ease pressure on GPs so they could focus on helping those in at-risk groups and patients with other illnesses. The service was available 24 hours a day, seven days a week to facilitate quick patient access to the antivirals.

Patients could telephone or go online to access the service. After answering questions about their illness patients were given, where appropriate, a unique reference number to take to a nearby antiviral collection point. Some high-risk patients, such as the under-fives, were directed to their GPs.

During the treatment phase protocols from the DoH were amended to enable patients to receive antivirals after the initial 48 hours of symptoms. The National Pandemic Flu Service decided that symptomatic individuals who had had influenza symptoms for up to seven days would be eligible for treatment with an antiviral.

As part of the national programme NHS North Lancashire opened antiviral collection points for issuing oseltamavir and zanamivir. Two of the collection points were initially located at the primary care trust’s two bases in Lancaster and Wesham. PCT staff were trained to take on new roles and responsibilities and rooms were rearranged to accommodate the antiviral collection points.

The PCT was well prepared for both the pandemic and opening of the collection points thanks to the emergency planning work that had been taking place during the previous years. To cope with the increase in the number of cases and to offer better access to the antivirals, a local enhanced service was offered to community pharmacies to act as antiviral collection points and 10 extra centres were set up in the region as a result.

January 2010 saw the start of de-escalation of the original plans. The National Pandemic online and telephone influenza service was closed on 11 February 2010. PCTs were advised to close all remaining antiviral collection points by the end of March 2010, with responsibility for issuing antivirals reverting to GPs via a normal FP10 prescription.

During the pandemic PCTs were collecting data for the DoH on patient demographics and number of antivirals issued to flu friends; the opening of the National Pandemic Flu Service allowed these data to be more easily collated.

According to the DoH, a total of 1,780,202 people were issued with a unique reference number from the National Pandemic Flu Service for oseltamivir between 23 July 2009 when it opened and 11 February 2010 when it closed. Out of these people 1,146,445 (64 per cent) collected their medicines from an antiviral collection point. This means that 36 per cent of individuals who had received authorisation did not collect the antivirals allocated to them via this route.

There were a number of patients in North Lancashire whose unique reference number was incorrectly transcribed and who were unable to collect the medicine using this number. Since the antiviral collection points were unable to assess patients for treatment, these patients, or their flu friends, had to be redirected to their GP to obtain new authorisation.

Method

This was a quantitative, descriptive and cross-sectional study, which sought to quantify the relationships between different variables within a group of individuals during their treatment. The study was descriptive as there was no attempt to change the behaviour or conditions of the treatment or actions of the individuals; the study merely identified and measured their behaviour.

The study focused on variables of interest in the sample to determine the relationships between them. Although this study only provides a case-study analysis of the individuals and treatment it does reveal relationships between the variables and has enabled suggestions of causal connections to be made. Through combining the results of this study with other research studies that are more methodologically advanced, we are able to draw reasonable conclusions and recommendations.

This study was put together by a joint group, which included representatives from medicines management, public health and research and development. The questionnaire was disseminated throughout the research and development governance team and the Caldicott guardian for the PCT for expert opinion. It was concluded that it did not require full NHS ethical approval as it came under the criteria for clinical audit.

The survey was handed out to 1,000 flu friends collecting patients’ antiviral medicines from our antiviral collection points during the months of August and September 2009. The influenza friend was instructed to ask the patient, or the patient’s representative, to complete and return the survey on the patient’s recovery.

The first 500 surveys were handed out during August and another 500 were handed out during September. Three extra questions were added to the second batch of surveys in September. We decided to determine how many days of symptoms patients had experienced when they received the antiviral, whether they had already received an antiviral for swine influenza before this issue and whether they would want to receive a swine influenza vaccine were one available.

The vaccination was still being developed and was not yet available at the time of the survey. Patient identifiable data was not collected and patients were asked to fill in an equality and diversity questionnaire.

Results and discussion

Patient demographics

During August and September 2009 when the survey was carried out, 1,780 antivirals were issued to flu friends at antiviral collection points in North Lancashire; 1,759 issues (99 per cent) were for oseltamivir and 21 issues (1 per cent) were for zanamivir. The first-choice antiviral was used for 99 per cent of cases during these two months.

During the early part of July before the National Pandemic Flu Service opened only GPs were issuing authorisation notes for antivirals. Their prescriptions mirrored those of the national influenza line; 99 per cent were for oseltamivir and 1 per cent for zanamivir. This shows that GPs were following the national protocol for prescribing antivirals during the pandemic.

Respondents to the survey represented a balanced cross section of patients. A total of 188 patients responded, a response rate of 18.8 per cent. This was considered to be good since it was not possible to send out reminder questionnaires. The group of patients who had the highest percentage response rate to the survey was females aged 66 years and over.

During the initial phases of the pandemic, in compliance with DoH protocols, GPs were asked to target patients who were considered to be at greatest risk if complications developed and to prioritise these patients for treatment with antivirals. However during July, shortly before the National Pandemic Flu Service opened, all patients were given equal access to treatment as part of the treatment-for-all phase.

Demographics collected and patients’ reporting on their comorbidities shows us that treatment was available to the whole population of North Lancashire during the time of the survey. Only 28 per cent of respondents had comorbidities that classified them as being at high risk of complications.

The percentages were mostly in line with PCT prevalence taken from Quality and Outcomes Framework (QoF) data1, except for that of people with asthma or lung disease. Nineteen per cent of patients in the study reported having asthma or other lung disease; however the PCT prevalence is only 8.4 per cent of the total population.

This increased rate of accessing antivirals seen in patients with asthma or other lung diseases may have happened for a number of reasons, such as patient concerns with developing complications of influenza, increased influenza illness rates in patients with lung disease or people may have been accessing antivirals for prophylactic use.

Symptoms and duration of influenza

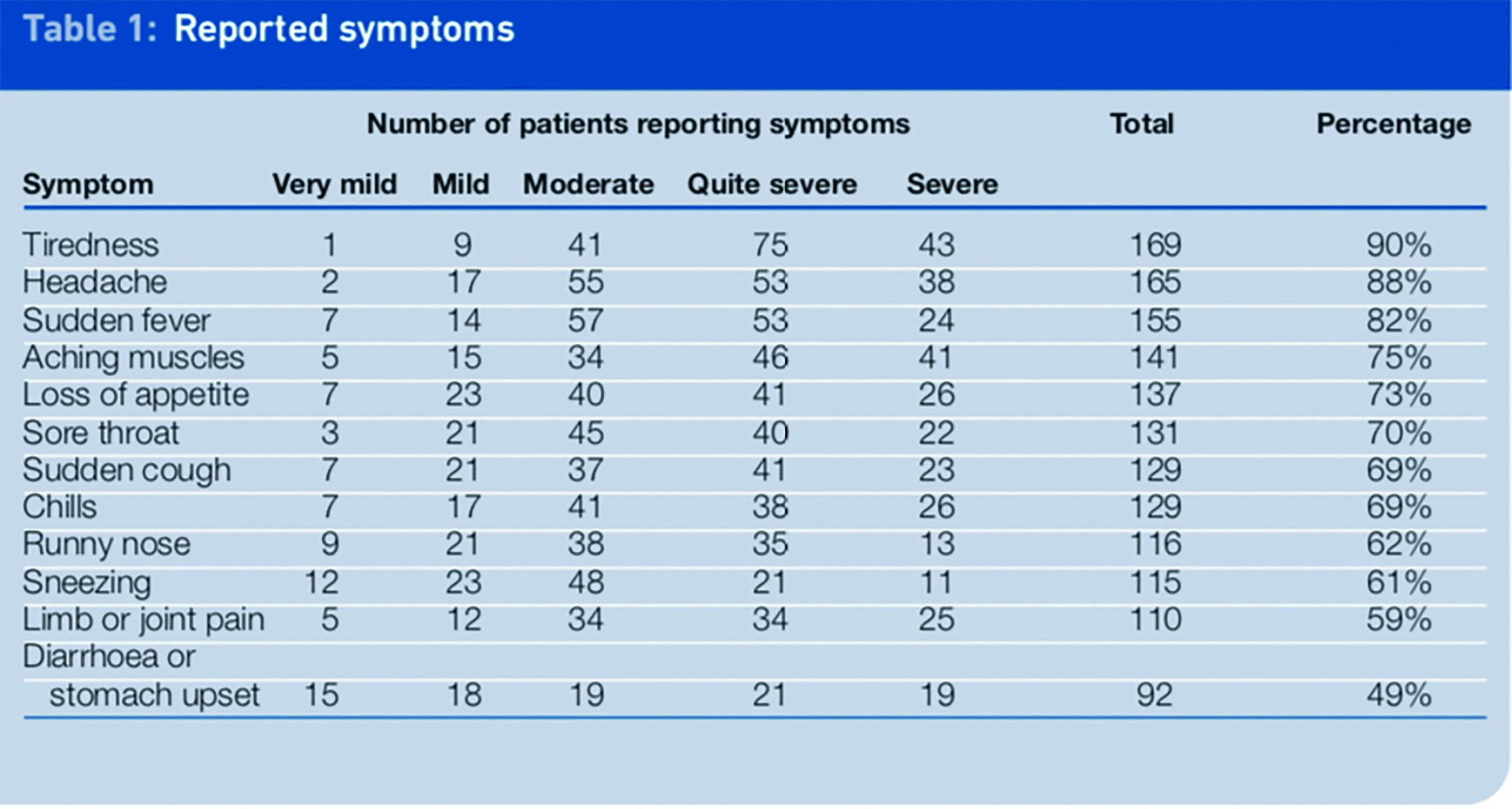

Patients were given a list of symptoms of swine influenza and asked to report on the severity of each symptom that they experienced. Patients were also asked to report or comment on any other symptoms that were not on the list provided.

The most commonly reported symptoms were tiredness (90 per cent of patients), headache (88 per cent) and sudden fever (82 per cent). All of the established symptoms of the H1N1 virus were reported in a high percentage of patients as shown in Table 1. The most commonly reported adverse drug reactions for oseltamivir from studies are nausea, vomiting and headache, with the occurrence of both nausea and vomiting shown to be statistically different between placebo and oseltamivir in clinical trials.2

Diarrhoea or stomach upset are recognised symptoms of swine influenza2 and were reported in 49 per cent of patients in the survey. As these symptoms can also be side effects of oseltamivir this result should be interpreted with caution since it may have been difficult for patients to distinguish between a symptom and a side effect. Other reported symptoms, which were not common to the H1N1 influenza virus, included chest pains, eye problems, earache and wheezing.

Symptoms reported in the study were most frequently quite severe (31 per cent) or moderate (31 per cent), with 20 per cent of symptoms reported as being severe. Very mild or mild symptoms were only reported in 18 per cent of respondents (n=1,589).

During the early stages of the pandemic symptoms were described by the DoH as being mostly mild and resembling those of seasonal influenza. Our data conflict with this description possibly because symptoms became more severe after the initial phase of the pandemic; patient perceptions of severity of symptoms differed from those of healthcare professionals, or people with mild symptoms may have chosen not to use the antivirals.

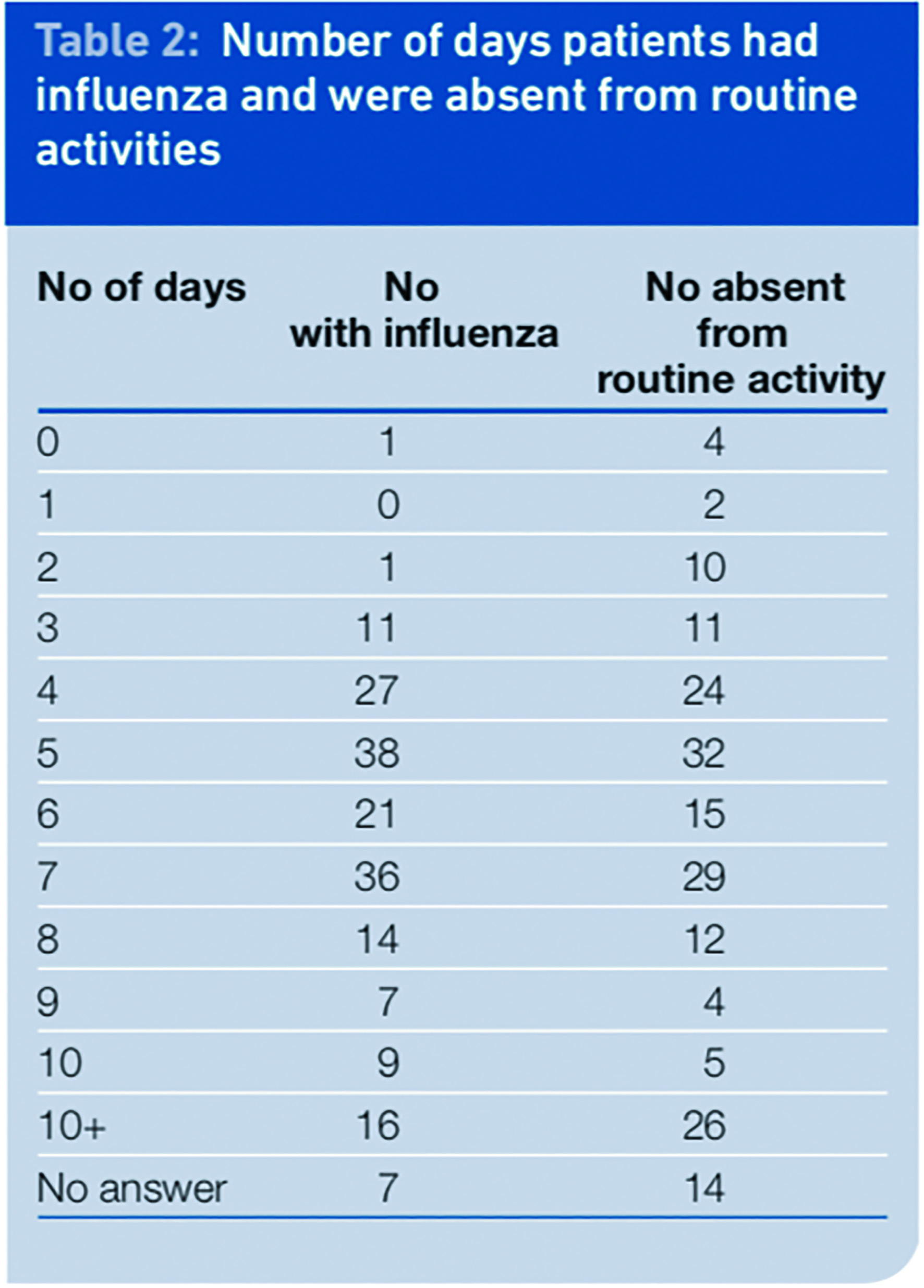

We found the most likely duration of swine influenza illness to be between four and seven days, which was consistent with a higher incidence of a period away from work or routine activities of between four and seven days. However there were a proportion of people (32 per cent) who returned to routine activities while they still had symptoms.

It is difficult to determine what the individual routine activities comprised; no differentiation was made between household activities and work or school. This therefore does not tell us how many people returned to work or left the boundaries of their home while they still had influenza symptoms. However, it potentially highlights the need to reinforce the message to patients to stay at home while they have symptoms to limit the spread of the infection, because prevention is the most effective way to reduce the burden and costs of influenza.

One of the areas flu friends oftten asked for advice about was when patients could return to work. These questions were redirected to the pharmacist on duty at the centre, because staff working as issuers were working to a DoH action card and were instructed only to give information to the influenza friend to tell the patient to start taking the medicine as soon as possible.

An information leaflet was supplied to the influenza friend to give to the patient and this advised patients to stay at home until they felt well, although no specific information was given by the DoH about returning to work.

Nine per cent of patients had symptoms for more than 10 days. We did not collect data to determine how many actual days of symptoms this group of people experienced; the choice of answer on the survey was simply “more than 10 days”. This group could have represented patients who had developed complications or a secondary infection.

Effectiveness of treatment

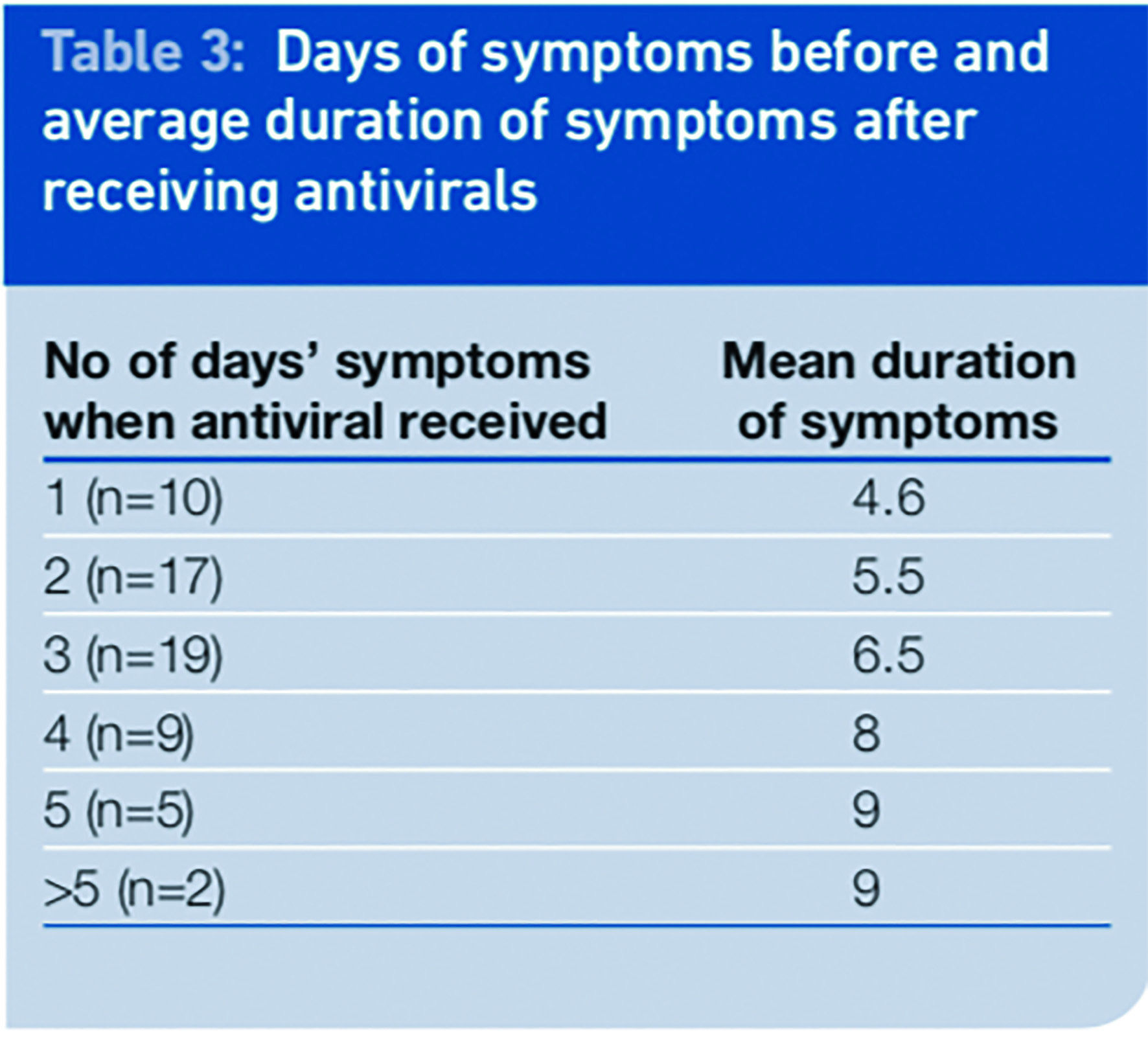

In the September survey we evaluated the benefits of early intervention with an antiviral. Patients were only included in this analysis if they had completed the course of antivirals and supplied the data needed (n=62).

The number of eligible respondents was small and this should be taken into account when evaluating the results. We looked at the relationship between the time from onset of symptoms to receiving the antivirals and the duration of the symptoms. There was a correlation between the day of receiving the antiviral after symptom onset and the illness duration, such that the duration of illness was shorter the earlier treatment was received.

The mean period of illness was 6.3 days for the 62 patients in this analysis; however patients started their treatment on different days and there was no control group of patients who did not take any antivirals.

When antivirals were given one day after the start of illness the mean duration of symptoms was 4.6 days, which is a reduction of 1.7 days of illness or 27 per cent compared with the mean of the total group.

When received two days after onset the mean reduction was 0.8 days or 13 per cent . There was no reduction in mean duration of illness when the antivirals were received three days or more after the onset of symptoms. If received in the first 48 hours of illness the mean duration of symptoms was reduced by 1.2 days (19 per cent) to 5.1 days.

We had no placebo group in our study. However, our findings support evidence from randomised controlled trials that, if taken within the first 48 hours of symptoms of influenza, an antiviral can reduce the duration of illness, and the earlier taken the better the outcomes.2–5

One study found that patients starting oseltamivir within 24 hours of symptom onset had a 37 per cent reduction in illness duration compared with placebo.6 Other studies looked at the effects of treatment within the first 12 hours of symptoms and found the benefits to be even greater.

The IMPACT (immediate possibility to access oseltamivir treatment) study looked at the benefits of early administration of oseltamivir in influenza; the results showed that treatment within 12 hours of symptom onset further reduces the duration of illness by 3.1 days or 41 per cent compared with starting treatment 48 hours after start of treatment.5

For every six hours earlier that oseltamivir was initiated, the predicted median illness duration is shortened by an acceleration factor of 1.09 (9 per cent). The study went on to say that virus replication in influenza peaks in the respiratory tract in about 24 to 72 hours and drugs like oseltamivir that inhibit virus replication must be administered in the first 48–72 hours of illness, and preferably as early as possible.5

Studies have shown that early intervention with oseltamivir is strongly associated with a shorter time to return to baseline activity, a reduction in the duration of fever and a reduction in severity of illness.3–5 Reduced severity of symptoms is seen when an antiviral is started very early, for example during the first 12 hours of illness.4,5 Our study did not capture data when antivirals were given as early as 12 hours. Our findings showed that there was no significant difference in the severity of symptoms when the antiviral was commenced in the first 48 hours of symptoms.

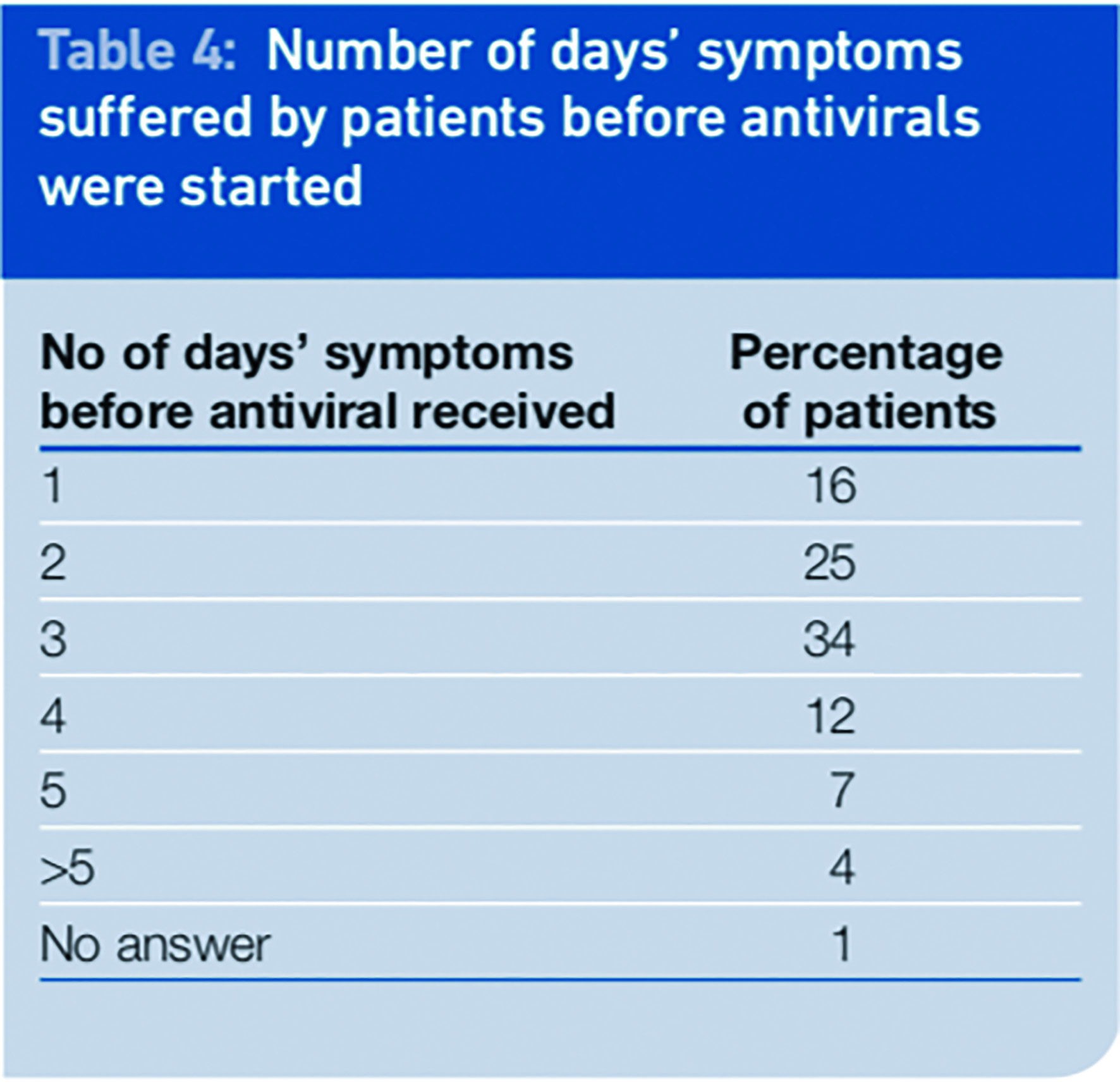

Evidence suggests that to be effective at reducing the duration of illness oseltamivir should be taken within the first 48 hours of the start of symptoms. Also the earlier treatment starts the better the outcomes. Data from our survey show that 57 per cent of patients in the study did not receive their antivirals until after the first 48 hours of influenza symptoms or illness.

Processes had been put in place to enable patients to access the antivirals as soon as possible, which suggests that the late collection of the antivirals may have been due to patient or influenza friend factors. Patients may have benefited from a clear message to obtain their antivirals as soon as possible after influenza symptoms develop.

The information leaflet produced by the DoH, which was handed to the influenza friend at the same time as the antiviral, advised the patient that the antiviral would aid recovery if taken within seven days of the symptoms developing. This differed from the information leaflet that was distributed to all households at the start of the pandemic: it advised that patients would benefit from antivirals if taken within two days of getting influenza symptoms (DoH).

At some time during the pandemic the DoH changed its guidance on the effectiveness of the antivirals. A potential recommendation from this research would be that the most important consideration during an influenza pandemic should be to concentrate on getting antivirals to patients as soon as possible to reduce the impact of influenza on the individual and society.

The National Pandemic Flu Service was opened to facilitate an early intervention. However, it involved a two-step approach; step 1 entailed obtaining a unique reference number and step 2 involved a visit to an antiviral collection point to obtain the antivirals. A one-step approach of authorisation and issue might allow patients faster access to the antivirals.

Medicines management

As part of the second wave of surveys in September, patients were asked to report on how many days of symptoms they had suffered before they received their antiviral. We can equate this to being the day they started to take the medicine because part of the issuing role was to advise the influenza friend to deliver the medicine to the patient straight away and instruct the patient to start taking it immediately.

The results of the survey show that in most cases antivirals were issued after 48 hours of symptoms of swine influenza (57 per cent). Only 41 per cent of patients received the antiviral in the first 48 hours of symptoms. Medicines were most likely to be issued on the third day of symptoms (34 per cent) and some patients received antivirals on day five of symptoms or beyond.

Compliance can be an issue with antimicrobial medication. Evidence suggests that compliance with the instruction to finish courses of antibiotics can be between 57 per cent and 74 per cent , with a mean compliance of around 62 per cent.7 This may be because patients start to feel better or they may suffer side effects and so stop taking the medicine.

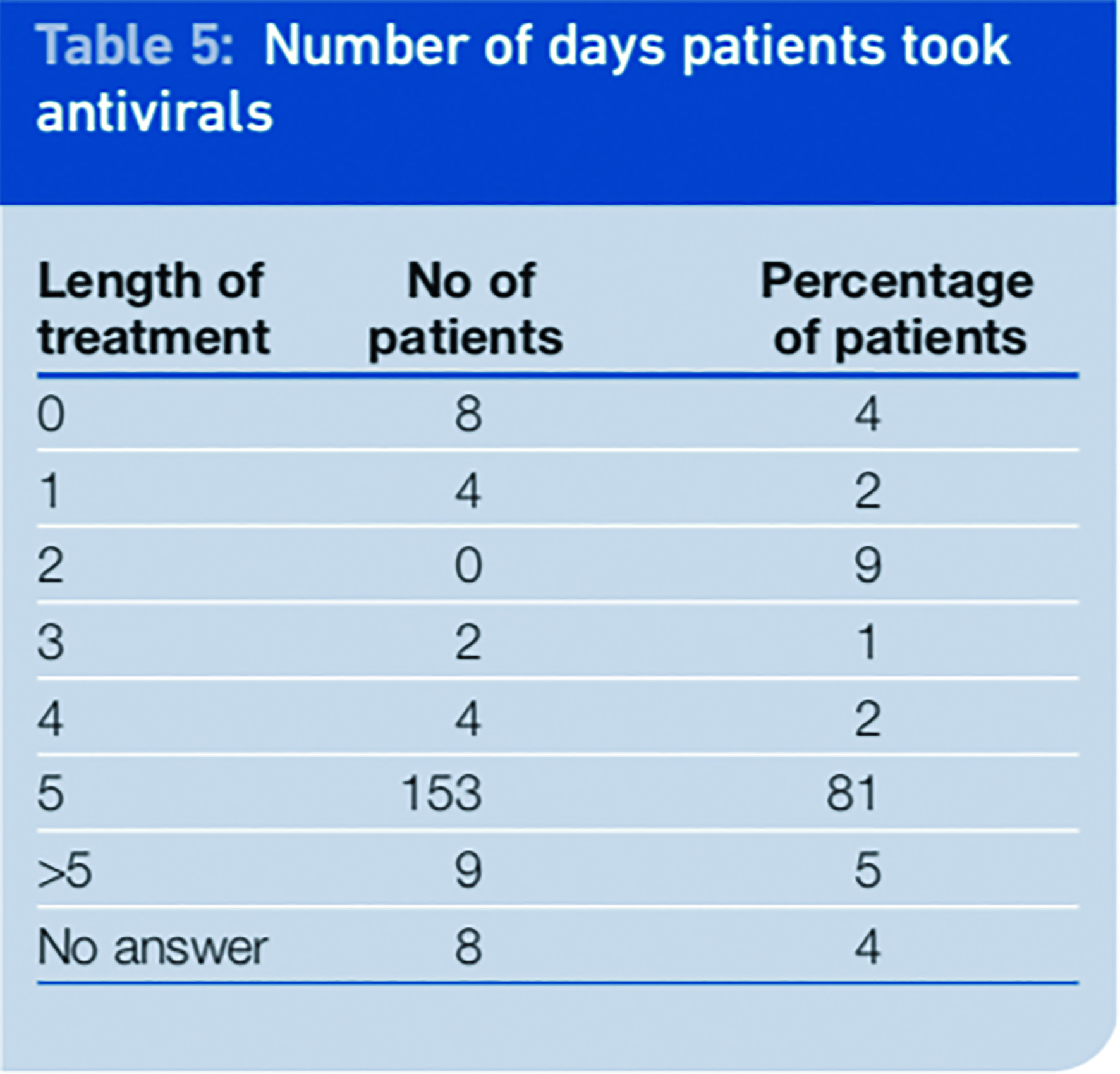

We asked patients to report on compliance and if they did not fully comply to explain why not. Compliance was shown to be generally good among the respondents to the survey, with 86 per cent of patients claiming to have taken their medicines for five days or more. A total of 9 per cent of patients were non compliant with their medication. That figure includes 4 per cent who never started the treatment and 5 per cent who stopped short of the full course of five days’ treatment. We found compliance to be better than that seen with antibiotics in other studies.7

The main reason for non-compliance was not starting the course of medication (eight patients). Reasons given for this included: being worried about potential side effects; not having influenza (either confirmed by a GP or NHS Direct or suspected by themselves); or feeling better. Patients who did not complete the course of treatment after they had started gave the reasons that symptoms had gone or were better, they suffered side effects, they were afraid of side effects or they thought they did not have swine influenza.

Analysis of the data showed that only 31.5 per cent of patients received the antivirals in the first 48 hours and completed the course.

Effective medicines management is about getting the right drug to the right patient at the right time. This signifies, among other things, ensuring that the medicine is effective, necessary, appropriate, timely and safe.

During a pandemic, influenza disrupts the normal activities of individuals and results in a considerable burden on society because of the large number of people incapacitated by the illness. For influenza the direct costs relating to hospital admission and treatment occur more frequently in high-risk patients.

In addition to the direct costs of medical care, there are substantial indirect costs, largely attributed to absenteeism and loss of work productivity. Estimates of indirect costs show that they can be five- to 10-fold higher than direct costs and can account for 80 to 90 per cent of the total costs.8

Prevention of influenza is the most effective way of reducing costs; however targeted treatment should also reduce total costs. The expected benefits of antiviral treatment in a pandemic are:

- Reduction of illness duration and therefore more rapid mobilisation of affected individuals including essential workers

- Possible reduction in admissions to hospital of infected individuals with complications

- Reduction of subsequent antibiotic use by individuals with secondary infections

Evidence to date does not suggest there will be a reduction of overall mortality, however this cannot be ruled out.8 An increase in consultations for influenza-like illness in general practice intensifies pressure on primary healthcare services; the National Pandemic Influenza Service was created to lessen this burden.

Evidence suggests that to be most effective the course of antivirals should be started within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms. There is little evidence to support their use after 48 hours. Efficacy of oseltamivir, as reported in its summary of product characteristics, has been demonstrated when treatment is initiated within two days of first onset of symptoms.1 This is based on studies of naturally occurring influenza in which the predominant infection was influenza A.

Influenza H1N1 is a subgroup of the influenza A virus.6 Both oseltamivir and zanamivir are licensed for use within 48 hours (within 36 hours for zanamivir in children) of the first symptoms.6,9

The provisional clinical management guidelines for treating patients during an influenza pandemic suggest that there may be two exceptions to the advice not to start treatment later than 48 hours after onset of illness. These are for patients who are immunosuppressed and patients who are severely ill but who have not been admitted to hospital for non-clinical reasons. The guidelines go on to say there is no strong evidence to support antiviral use in these exceptional situations.10 A systemic review and meta analysis found that oseltamivir did not reduce influenza-related lower respiratory tract complications.11

Side effects and patient experiences

Some patients did not start taking the medicine because of the possibility of side effects; others stopped taking it because they believed they had experienced side effects. Forty-nine patients (26 per cent) thought they had side effects from the antivirals and 125 (66 per cent) said they had no side effects; 14 patients did not answer this question.

The survey was aimed at all age groups and it would have been difficult to determine if a young child had experienced side effects; this may be why not all responders answered this question.

The discontinuation rate due to side effects was only 1.6 per cent (three patients). Of the 49 patients who thought they had suffered side effects only seven (14 per cent) said they reported this to their GP or pharmacist.

Studies show that in adults the most likely side effect of oseltamivir is vomiting and nausea, mostly once on the first or second treatment day. This usually resolves spontaneously within one or two days. Nausea occurs in around 13.6 per cent of people and vomiting in around 11.2 per cent of people; the incidence of nausea is reduced when the first dose is taken with food.2–5 Studies show that the numbers of people who discontinue oseltamivir due to this side effect are small. In children the most common reported side effect with oseltamivir was vomiting.5 Adverse effects with zanamivir are very rare and include bronchospasm, dyspnoea, facial and oropharyngeal oedema and rash.9

Patients were questioned on whether they thought the antiviral medicine they received had helped relieve their symptoms or reduce the duration of their illness. For this question patients were asked to tick any box that applied. The results show that 70 per cent of patients believed that the antivirals helped: 52 per cent of patients thought that the antiviral reduced the duration of their illness and 53 per cent thought that their symptoms were relieved in some way.

Just 14 patients (7 per cent ) thought that they did not help at all and 22 per cent either did not know or left the answer blank. Some patients (35 per cent) thought the antivirals reduced symptoms and the duration of their illness.

We only found evidence that antivirals reduced the duration of illness when given in the first 48 hours and we found no evidence to suggest that symptom severity was reduced.

Only 41 per cent of patients received the antivirals in the first 48 hours and just 31.5 per cent received them in the first 48 hours and completed the course. This shows that patients’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the antivirals exceeded the evidence.

How people perceive whether medication assists in their illness affects their compliance and willingness to request the medicine should the need arise again. A high percentage of patients thought the antivirals helped in their recovery when evidence from this research shows they had little or no effect.

Of the patients who received the antiviral after 48 hours, 82 per cent (n=39) thought that it still helped their recovery by either relieving symptoms or reducing illness duration.

This high percentage (82 per cent, n=17) was also seen in patients who received the antivirals on days 4 and 5 of illness, supporting the idea that patients believe that antimicrobial medication assists respiratory illnesses caused by pathogens even when there is no evidence to support this and recovery was actually the natural course of the disease.

When asked whether they would have a vaccine if it were available, 52 per cent said “yes”, 8 per cent said “no” and 40 per cent were undecided.

Only one patient had been prescribed antivirals for swine influenza during the past year. This patient was in the age band 0 to 5 years, had influenza for eight days and did not receive the antiviral until day 4 of symptoms.

As a result of using the National Pandemic Influenza Service two patients (1 per cent) who responded to the survey received a misdiagnosis: one patient had an Escherichia coli infection and the other had a kidney infection.

Conclusion

During the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009 access to antivirals was extended to all patient groups as part of the “treatment for all” phase. The severity of symptoms reported was higher than that perceived by the DoH and health professionals at the start of the pandemic and although the neuroaminidase inhibitors have been shown to reduce severity of symptoms in influenza, this effect was not demonstrated in this study.

The antivirals used in the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009 reduced the duration of illness when given in the first 48 hours of influenza-like illness by a mean of 1.2 days. There is no evidence to support their efficacy when given after 48 hours of symptoms.

If the results of this small study can be extrapolated to the general population during the pandemic, we can conclude that systems put in place for the safe issue of antivirals during the pandemic, including the use of the National Pandemic Influenza Service, failed to achieve one of the desired outcomes of getting the medicine to the patient as early as possible for most patients. This may have been partly due to patients not accessing the service until a few days into their symptoms.

More than half of all issues of antivirals during the pandemic may not have been in line with the evidence-based recommendations for treatment.

Patients have a strong belief that antivirals help recovery in a influenza pandemic in situations where there is no evidence that this is the case. Coupled with the fact that patients often accessed the influenza service after the first 48 hours, this demonstrates that the public often have a poor understanding of how antivirals work.

Patients should be given more information on antiviral medication to empower them to make informed decisions on their treatment. There should be a clear message to the public during a pandemic to access the antivirals as soon as possible after the onset of influenza symptoms and this should be before 48 hours; the earlier they start taking them the better the outcomes.

The most effective way to reduce the costs to society of an influenza pandemic is to prevent spread of the disease and to start treatment with neuroaminidase inhibitors as early as possible following the onset of symptoms. The recommendation is that the focus during a pandemic should be on these two elements.

This study shows that reduction of illness duration was not optimal due to the late collection of antivirals by most people; this could be seen as an inefficient use of resources. However, we do not know if we would have seen a difference in the pattern of the pandemic and spread of the disease if the UK had not used antivirals in the way it did.

Another piece of research could compare the spread of the disease in the UK with spread in a country that used antivirals more conservatively. Trials are urgently needed to investigate whether neuroaminidase inhibitors are more effective than symptomatic treatment and hygiene and barrier measures to interrupt influenza transmission in healthy adults.

About the authors

Julie Lonsdale, BSc, MRPharmS, is deputy head of medicines management, and Rosalind Way, MA, is head of research innovation and development, both at North Lancashire Teaching Primary Care Trust

Correspondence to: Ms Lonsdale (email julie.lonsdale@northlancs.nhs.uk)

References

- QoF prevalence reports. Available at: www.nhscomparators.nhs.uk/NHSComparators/ (accessed on 4 June 2010).

- Summary of product characteristics. Tamiflu 75mg capsules. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/10446/SP C/Tamiflu+75mg+hard+capsule/ (accessed 21 May 2010).

- Kawai N, Ikematsu H, Iwaki N, Satoh I, Kawashima T, Maeda T et al. Factors influencing the effectiveness of oseltamivir and amantadine for the treatment of influenza: A multicenter study from Japan of the 2002-2003 influenza season. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2005;40:1309-16.

- Stiver G. The treatment of influenza with antiviral drugs. CMAJ 2003;168:49-56.

- Aoki FY, Macleod MD, Paggiaro P, Carewicz O, El Saey A, Wat C et al. Early administration of oral oseltamivir increases the benefits of influenza treatment. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2003;51:123-129.

- Nicholson KG, Aoki FY, Osterhaus ADME, Trottier S, Carewicz O, Mercier CH et al. Efficacy and safety of oseltamivir in treatment of acute influenza: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 355:1845-50.

- Kardas P, Devine S, Golembesky A, Roberts C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of misuse of antibiotic therapies in the community. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2005;26:106-113.

- Szucs T. The socio-economic burden of influenza. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 1999;44:11-15.

- Summary of product characteristics. Relenza inhaler. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/2608/SPC /Relenza+5mg+dose+inhalation+powder./ (accessed on 21 May 2010).

- British Infection Society, British Thoracic Society and Health Protection Agency. Pandemic Flu Clinical management of patients with an influenza-like illness during an influenza pandemic provisional guidelines. 2006; version 10.5.

- Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, del Mar C. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal 2009;339:b5106.

- World Health Organisation, WHO. Available at: www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/en/index.html (accessed on 21 May 2010).

- NICE technology appraisal guidance 158. Oseltamivir, amantadine (review) and zanamivir for the prophylaxis of influenza. 2008.

- The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Available at: www.rpsgb.org.uk/flu/ (accessed on 21 May 2010).

- Pechère JC, Hughes D, Kardas P, Cornaglia G. Non-compliance with antibiotic therapy for acute community infections: a global survey. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2007;29:245-253.

- National Prescribing Centre. The benefits and risks of oseltamivir (Tamiflu) for the treatment of influenza. MeReC Extra Issue No.4.