Abstract

Aim

To determine if suitably trained pharmacists and dietitians can safely and effectively prescribe peri-operative parenteral nutrition.

Design

Assessment by two blinded independent observers.

Subjects and setting

A pharmacist and a dietitian at Hope Hospital, Salford.

Results

370 separate decisions were made. Decisions were of major clinical benefit in 2–8% of cases, and of at least positive value in 46–63% of cases. No decisions were considered harmful or to have exposed patients to risk.

Conclusions

Pharmacists and dietitians given suitable training can safely prescribe parenteral nutrition, and may be as, if not more, capable of prescribing than junior medical staff. Consideration should be given to developing extended clinical roles for these health professionals.

Although there have been advances in the formulation and delivery of nutritional support, provision in the peri-operative period remains associated with a high incidence of complications, which include feed-related morbidity and adverse events related to nutrient delivery.1

Provision of safe and optimally effective nutritional support requires a satisfactory knowledge base, yet concern has been expressed on both sides of the Atlantic about the adequacy of training in the fundamental principles of clinical nutrition2–5 and even simple fluid and electrolyte therapy,6 during undergraduate and early postgraduate medical training.

Potential deficiencies in the knowledge and training of junior doctors in nutrition and metabolic care for sick surgical patients are likely to be compounded by the introduction of the European Working Time Directive (EWTD), which has introduced a legal requirement that employing authorities restrict junior doctors’ working hours to a maximum of 48 hours per week. Potential training deficiencies could be compounded if proposals to shorten postgraduate medical training7 are implemented. These initiatives represent a major challenge for the delivery of high quality healthcare, because of their manpower implications8 and their potential impact on training.9 It has been proposed that the shortfall in medical input in key clinical areas might be addressed by the development of extended clinical roles for other health professionals. For example, the NHS Plan stated that there would be over 6,500 more healthcare professionals by 2004, with the introduction of consultant therapists to help reduce junior doctors’ working hours.10

The extension of prescribing rights, including supplementary prescribing, defined as a voluntary partnership between a responsible independent prescriber (a medical practitioner) and a supplementary prescriber (another health professional) to implement an agreed patient-specific clinical management plan11 has been introduced to assist in the creation of these new roles, with the aim of providing patients with quicker and more efficient access to medicines and improving patient safety.

The shortfall of core knowledge and training of junior doctors in nutritional and metabolic care, combined with the considerable expertise available from allied health professionals and the potential applicability of supplementary prescribing makes nutritional support an area of obvious clinical relevance for the development of extended clinical roles for allied health professionals.

Since the proposal, in 1992, that nutritional support should be delivered by a multidisciplinary nutritional support team (NST), comprising medical staff, specialist nurses, pharmacists and dietitians,12 NSTs have been shown to improve the safety13 and cost effectiveness14 of nutritional support in hospitals.

The combination of poorly trained junior medical staff and experienced and motivated allied health professionals with a background of multidisciplinary team working suggests that the development of an extended role for pharmacists and dietitians in the prescribing and administration of nutritional support might compensate for the lack of junior medical expertise in this area, and facilitate the provision of a clinical service that is as effective and at least as safe as that currently available.

Salford Royal Hospitals NHS Trust was chosen by the Changing Workforce Programme, part of the NHS Modernisation Agency, as a pilot site to explore the role of the consultant dietitian. Following discussions with the hospital trust nutrition steering group, the management of short-term parenteral nutrition was identified as a potential area for study and clinical protocols were devised to allow allied health professionals to undertake, in a carefully controlled manner, peri-operative nutritional and metabolic support tasks that would normally be delegated to junior hospital doctors.

We report here the results of a prospective study, which tested the hypothesis that a suitably trained dietitian and pharmacist could independently manage the provision of short-term peri-operative parenteral nutrition with levels of safety and clinical effectiveness that were satisfactory and at least comparable to those expected from junior medical staff.

Methods

Specialist training of allied health professionals

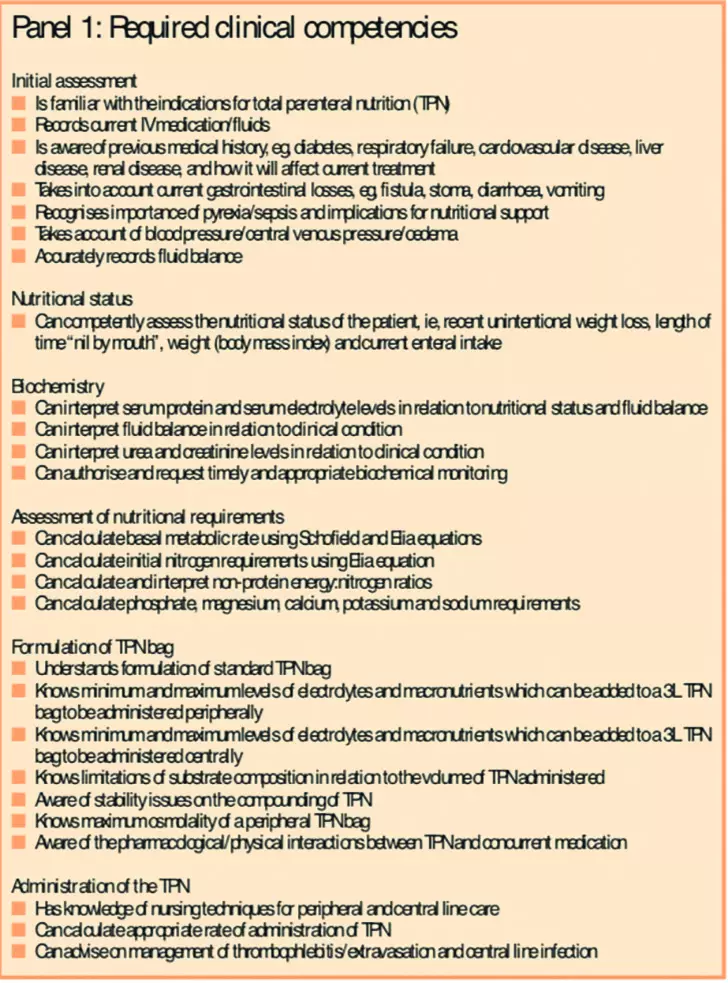

Additional training on the clinical indications for, and management of peri-operative nutritional support was provided to an experienced dietitian and pharmacist from the NST at Hope Hospital, from the consultant medical staff. The training programme lasted three months and included attendance at ward rounds, tutorials and at the Care of the Critically Ill Surgical Patient Course organised by the Royal College of Surgeons, which includes a significant element on nutritional management of the critically ill postoperative patient.15 The dietitian and pharmacist provided training for each other in their professional competencies. At the end of the training period, both were formally assessed by the consultant medical staff against a series of predefined clinical competencies (Panel 1).

Patients

All patients in whom parenteral nutrition was initiated as part of routine peri-operative care by the surgical unit were included in the study. Although the decision to initiate parenteral nutrition was taken by the consultant in charge of the patient’s overall medical care, subsequent decisions about the administration and formulation of parenteral nutrition were taken by the dietitian and pharmacist. The junior medical staff were advised about the requirements for haematological and biochemical investigation and the consultant was informed when a decision was made to stop or alter the route of nutritional support.

All patients who needed parenteral nutrition before or after general surgical procedures on the general surgical wards or the surgical high dependency unit were included in an unselected, consecutive manner, irrespective of the nature of surgery undertaken. Patients on the intensive care unit or the highly specialised intestinal failure unit, with complex nutritional and critical care requirements were excluded from this study.

Study design

When the consultants were satisfied with the level of competence demonstrated by both individuals, the referral and management process for parenteral nutrition was altered. Previously, once the NST had approved a request for nutritional support, the day-to-day management of parenteral nutrition was undertaken by the junior medical staff of the relevant clinical team and the NST provided advice and support only when changes to the nutrition regimen and/or decisions about cessation of nutritional support were felt to be required. After the adoption of the study protocol, decisions about the continued need for nutritional support, the appropriate route, day-to-day provision of nutritional, fluid and electrolyte requirements and initial management of nutrition-related complications, previously undertaken by junior medical staff, were instead referred by the nursing staff to the dietitian and pharmacist in the first instance. Decisions about nutritional support were communicated daily by dietitian and pharmacist to the relevant medical team, but only the consultant was permitted to make alterations to the programme of nutritional support and the nature of and reasons for alteration were communicated by the consultant to the dietitian and pharmacist and recorded prospectively.

Measurement of outcome

In each case, detailed prospective collection of data including patient demographics, underlying diagnosis, indication for treatment, route of administration of parenteral nutrition, length of time on parenteral nutrition, nutritional status, nutritional requirements for fluid, macro and micronutrients, and justification for any clinical decision which was thought to directly influence the provision of nutritional support were recorded.

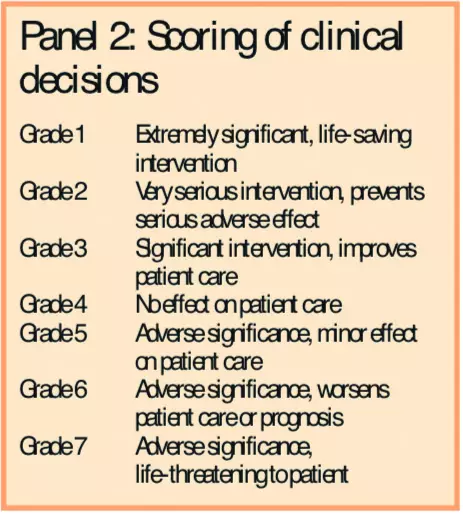

The clinical significance of each decision for every patient studied was subsequently graded independently by a consultant surgeon and consultant gastroenterologist, using the seven-point grading system of Overhage and Lukes16, (panel 2) in which the clinical importance of each therapeutic intervention was graded on a scale from 1 (an extremely significant, actual or potentially life-saving intervention) to 7 (an intervention which resulted in an adverse event of actual or potentially life-threatening significance). The consultants were unaware of the identity of the individual patients concerned and were blinded to each other’s conclusions.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data and data pertaining to length of treatment were analysed non-parametrically and presented as median (range). Statistical comparison between groups and individual consultant assessments was undertaken with Mann-Whitney U test. All data were analysed statistically using Graphpad Prism PC software software (Graphpad Prism Inc, San Diego, California) and P<0.05 taken as the level of statistical significance.

Results

The provision of peri-operative parenteral nutrition was evaluated in 46 (23 male, age range 22–79 years) patients, who were consecutively referred to the dietitian and pharmacist. Twenty-six patients (56.5 per cent) received parenteral nutrition via a peripheral line, 18 (39.1 per cent) via a central line and two (4.3 per cent) via a peripherally inserted central venous catheter.

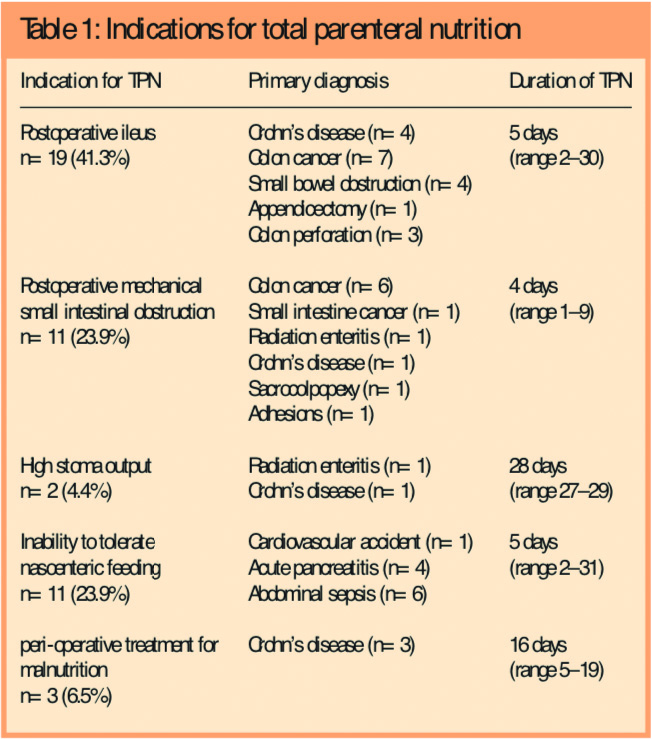

Parenteral nutrition was administered postoperatively in 43 patients (93.5 per cent) and was started pre-operatively, and then continued postoperatively in three patients (6.5 per cent). The indications for parenteral nutrition (Panel 3) were: paralytic ileus (n=19, 41.3 per cent), postoperative mechanical small bowel obstruction (n=11, 23.9 per cent), inability to eat and tolerate enteral nutritional support (n=11, 23.9 per cent), and presence of a high output jejunostomy (n=2, 4.3 per cent).

The median (range) length of parenteral nutrition was five (range 1–31) days, with a total of 368 patient days of parenteral nutrition for the entire cohort. The duration of TPN was similar in all groups, except in the patients with high output jejunostomy, who required a significantly longer period of post-operative TPN (P<0.001, MWU test).

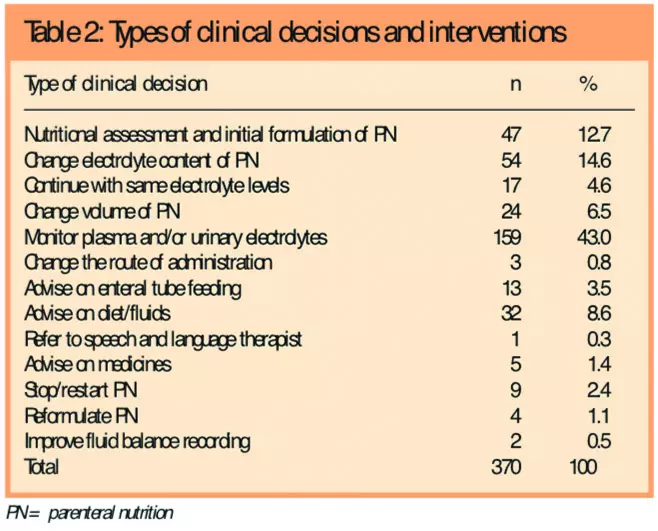

During this period the dietitian and pharmacist made a total of 370 individual decisions that directly affected the management of parenteral nutrition in these patients (Table 1).

Most of these (n=159, 43 per cent) were decisions to request measurement of electrolyte content in plasma or urine samples to ensure safe and adequate fluid and electrolyte provision. Over one third of the decisions (n=129, 34.9 per cent) related to the volume and/or formulation of TPN, either on initiation of treatment, or in respect of change that was felt to be subsequently required.

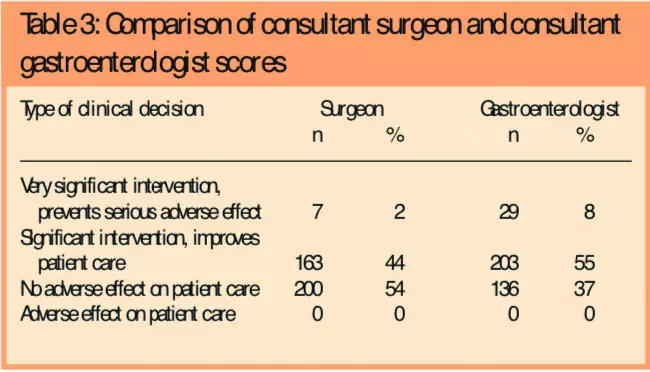

Assessment of the safety of the prescribing decisions (Table 2) revealed that neither consultant considered any of the decisions to have had a significant adverse effect on patient outcome.

Review of the clinical notes for each patient revealed no evidence of nutrition-related morbidity during the provision of parenteral nutrition to this patient group. Almost half of the clinical decisions made by the dietitian and pharmacist with respect to the administration of TPN were viewed as having being beneficial by both clinicians (n=170, 46 per cent surgeon, n=232, 63 per cent physician, Table 3). The surgeon considered 2 per cent of the decisions to have been of major benefit, and to have potentially prevented adverse events, whereas, in the physician’s, view, 8 per cent of decisions of this magnitude were of individual importance.

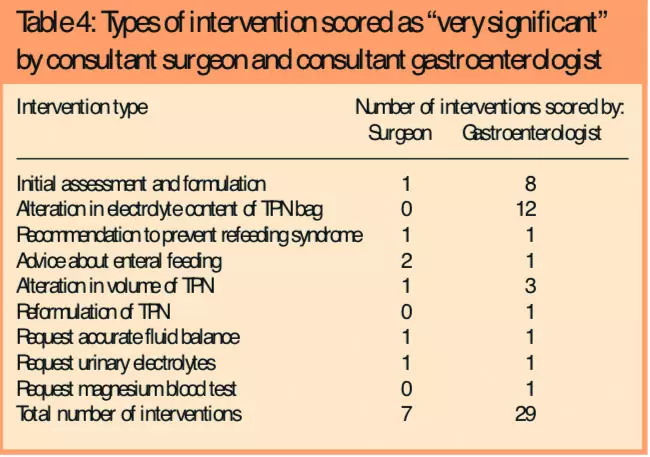

Individual interventions that were held to be very significant in preventing serious adverse events (Table 4) included strategies to prevent refeeding syndrome, alterations to the electrolyte content of TPN, and provision of advice to the medical team about cessation of TPN and resumption of enteral feeding.

There were significant differences when the opinion of surgeon and physician were compared, with the physician tending to categorise many of the changes in electrolyte composition as being of sufficient benefit to prevent adverse events (grades 1 and 2), while these interventions were more usually scored as of positive benefit only (grade 3) by the surgeon. Similarly, the physician concluded that the process of initial formulation of the TPN was likely to have prevented significant adverse events, while these interventions were seldom regarded as being of equivalent significance by the surgeon.

Discussion

There has been growing concern about the medical school curriculum where the teaching of fluid and electrolyte balance and nutrition is concerned,3,5 and similar anxieties have been expressed with respect to postgraduate medical training.17 Studies of fluid, electrolyte and nutritional prescribing by junior medical staff in the UK have revealed alarmingly low standards of knowledge and clinical practice.18–20 The routine prescription of intravenous fluids and electrolytes has been shown to be almost invariably delegated to preregistration house officers.6,21 They are frequently unaware of the sodium content of the fluids they prescribe or the normal daily sodium requirement, fail to make reference to the daily fluid balance charts on almost 50 per cent of occasions and frequently prescribe excessive amounts of sodium.6

Although there are considerably fewer published data about levels of knowledge about parenteral nutrition among junior medical staff, it seems reasonable to conclude from the foregoing that junior medical staff will be even less well equipped to prescribe parenteral nutrition. While improvements in education are desirable, the recent streamlining of medical training engendered in Modernising Medical Careers7 seems unlikely to facilitate the acquisition of this knowledge, and the reductions in junior doctors working hours and the institutions of patterns of shift working associated with the EWTD may compound the ability of junior doctors to put theory into practice.

Although it is many years since the introduction of nutrition support teams was recommended12 the development of a culture of multidisciplinary teamworking recognises that health professionals other than clinicians may be better placed to deliver some aspects of complex treatments. Nutritional support teams have been shown to reduce inappropriate use of parenteral nutrition22 and to be associated with reduced complication rates as well as significant cost savings.23 We therefore considered it appropriate to examine the possibility of developing the roles of the dietitian and pharmacist beyond their traditional advisory roles in the nutritional support team and to determine whether they could safely take over the formal role as the principal prescriber of parenteral nutrition for a group of perioperative surgical patients.

The historical development of medical practice has led to the establishment of tight controls on the prescription of drugs. Traditionally, the ability to prescribe certain drugs in the UK lawfully has required recognition of the training and qualifications of medical practitioners, commensurate with inclusion on the medical register. There is sound justification for this practice, based on patient safety, since safe prescribing of drugs is most likely to be undertaken by individuals who have received training in the appropriate pharmacology and relevant clinical specialties. On the same basis, however, given the apparent lack of training and knowledge of medical graduates in clinical nutrition, it is unclear whether junior medical practitioners are the most appropriate individuals to prescribe parenteral nutrition. The rationale for the study was not simply based upon potential or actual cost savings, but on the recognition that other health professionals with a greater clinical focus and more expertise and knowledge in clinical nutrition might be better placed to prescribe parenteral nutrition safely.

The findings of the study suggest that parenteral nutrition can be safely administered by dietitians and pharmacists, provided they are given special training, a carefully constructed governance framework in which to work, and the support of senior clinicians. In order to provide a framework in which the dietitian and pharmacist could work without potential risk to patients, existing recommendations about the knowledge base and clinical support were followed closely in the study. There is no formally recognised training programme or accreditation process for dietitians and pharmacists with respect to prescribing TPN and the study was therefore undertaken under the auspices of the UK government Department of Health (DoH), with the clinical governance arrangements of the NHS trust ensuring patient safety. Before the clinical pathway for TPN prescription was altered, the consultants responsible for the project ensured that the dietitian and pharmacist had demonstrated to their satisfaction, during a series of interviews and clinical assessments, the requisite expertise. The clinical support24 and competency frameworks11, recommended by the DoH had been defined in advance by the clinicians, the pharmacist and dietitian, and had been established and tested before introduction of the project.

Although the surgeon and gastroenterologist were blinded to each other’s decisions about the clinical value of the interventions undertaken, they agreed that none of the 370 clinical interventions appeared to have been detrimental to patient care. Although the scoring system employed has been previously validated for healthcare prescribing in a different context16 there were differences of opinion about the clinical significance of the interventions. In general the gastroenterologist scored the changes in electrolytes and the initial assessment as more significant than the surgeon. Whether these differences reflect variations in clinical priorities or attitudes to uncertainty between clinical disciplines, as has recently been documented between surgeons and physicians,25 or individual prejudices, is unclear. However, while great care should be taken in attributing the opinions expressed by individual clinicians to the medical profession in general, the findings of the study indicate that there was agreement between the clinicians that not one of the 370 decisions made by the pharmacist and dietitian were associated with an adverse effect on patient care.

There has been considerable controversy about the development of extended prescribing roles for nurses.26 At present, pharmacists who have obtained the supplementary prescribing certificate can prescribe certain drugs, in partnership with an independent prescriber, using a patient-specific clinical management plan. Since May 2004, dietitians have been added to the list of allied health professionals who are allowed to supply and administer medicines under carefully controlled and tightly regulated circumstances, and it is envisaged that dietitians will shortly be able to participate in supplementary prescribing on the same basis, under the superv sion of the Health Professions Council.27

The aim of this study was to determine whether an appropriately trained dietitian and pharmacist could safely take over the prescription of short-term peri-operative parenteral nutrition in a cohort of surgical patients. The study did not aim to compare directly the performance of these allied health professionals with junior doctors and there will undoubtedly be significant challenges in designing a randomised clinical trial in order to compare the safety and efficacy of nutritional and fluid management undertaken by specially trained dietitians and pharmacists with current, junior doctor-based practice. Great care should be taken in extrapolating the findings to non-specialist units and it is also important to note that the findings of the study should not be taken to indicate that parenteral nutrition can be safely prescribed by dietitians and pharmacists under routine clinical conditions, but simply that some individuals may be able to do so safely, given appropriate training and an appropriate clinical governance framework.

The findings of the study do, however, provide support for further studies addressing this issue and suggest that such an approach would appear safe and potentially more cost effective than the current arrangements under which a great deal of peri-operative parenteral nutrition is administered.

About the authors

Kirstine Farrer, MPhil, RD, is consultant dietitian , Lindsay Harper, BSc, MRPharmS is principal clinical pharmacist, Jon Shaffer, FRCP, is consultant gastroenterologist, Nigel Scott, FRCS, is consultant surgeon, Iain Anderson, MD, FRCS, is consultant surgeon, and Gordon Carlson, MD, FRCS, is consultant surgeon at Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust and Salford Primary Care Trust.

Correspondence to: G. L. Carlson, Department of Surgery, Clinical Sciences Building, Hope Hospital, Salford M6 8HD (e-mail gordon.carlson@manchester.ac.uk).

References

- Woodcock NP, Zeigler D, Palmer MD, Buckley P, Mitchell, CJ, MacFie, J. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition: a pragmatic study. Nutrition 2001;17:1–12.

- Jackson AA. Human nutrition in medical practice: the training of doctors. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2001;60:257–63.

- Cooksey K, Kohlmeier M, Plaisted C, Adams, K, Zeisel, SH. Getting nutrition education into medical schools: a computer-based approach. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000;72:868S–76S.

- Makowske M, Feinman RD. Nutrition education: a questionnaire for assessment and teaching. Nutrition 1. 2005;4:2.

- Lo C. Integrating nutrition as a theme throughout the medical school curriculum. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000;72:882S–9S.

- Lobo DN, Dube MG, Neal KR, Simpson J, Rowlands BJ, Allison SP. Problems with solutions: drowning in the brine of an inadequate knowledge base. Clinical Nutrition 2001;20:125–30.

- Neville E. Modemising medical careers. Clinical Medicine 2003;3:529–31.

- Paice E, Reid W. Can training and service survive the European Working Time Directive? Medical Education 2004;38:336–8.

- Pickersgill T. The European working time directive for doctors in training. BMJ 2001;323:1266.

- Department of Health. The NHS plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

- Department of Health. Supplementary prescribing by nurses, pharmacists, chiropodists, physiotherapists and radiographers within the NHS in England: a guide for implementation — updated May 2005. London: Stationery Office, 2005.

- Lennard-Jones J. A positive approach to nutrition as treatment. London: King’s Fund, 1992.

- Naylor CJ, Griffiths RD, Fernandez RS. Does a multidisciplinary total parenteral nutrition team improve patient outcomes? A systematic review. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2004;28:251–8.

- Roberts MF, Levine GM. Nutrition support team recommendations can reduce hospital costs. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 1992;7:227–30.

- Hunter M, Carlson GL. Nutrition. In: Anderson ID (editor).Care of the critically ill surgical patient. London: Arnold,2003; pp113–125.

- Overhage JM, Lukes A. Practical, reliable, comprehensivemethod for characterizing pharmacists’ clinical activities. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacists 1999;56:2444–50.

- Flynn M, Sciamanna C, Vigilante K. Inadequate physician knowledge of the effects of diet on blood lipids and lipoproteins. Nutrition Journal 2003;2:19.

- Lane N, Allen K. Hyponatraemia after orthopaedic surgery. BMJ 1999;318:1363–4.

- Stoneham MD, Hill EL. Variability in postoperative fluid and electrolyte prescription. British Journal of Clinical Practice 1997;51:82–84.

- Nightingale JMD, Reeves J. Knowledge about the assessment and management of undernutrition: A pilot questionnaire in a UK teaching hospital. Clinical Nutrition 1999;18:23–27.

- Walsh SR, Walsh CJ. Intravenous fluid-associated morbidity in postoperative patients. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 2005;87:126–30.

- Saalwachter AR, Evans HL, Wlicutts KF, O’Donnell KB. Radigan AE, McElearney ST, et al. A nutrition support team led by general surgeons decreases inappropriate use of total parenteral nutrition on a surgical service. American Surgery 2004;70:1107–11.

- Kennedy JF, Nightingale JMD. Cost savings of an adult hospital nutrition support team. Nutrition 2005;21:1127–33.

- National Prescribing Centre. Maintaining competency in prescribing — an outline framework to help allied health professional supplementary prescribers. NPC, 2004.

- McCulloch P, Kaul A, Wagstaff GF, Wheatcroft J. Tolerance of uncertainty, extroversion, neuroticism and attitudes to randomized controlled trials among surgeons and physicians. British Journal of Surgery 2005;92:1293–7.

- Avery AJ, Pringle M. Extended prescribing by UK nurses and pharmacists. BMJ 2005;331:1154–5.

- National Prescribing Centre. Outline curriculum for training programmes to prepare allied health professional supplementary prescribers. NPC, 2004.