Introduction

The UK’s population is ageing. The percentage of the population aged 65 and over increased from 15 per cent in 1983 to 16 per cent in 2008 — an increase of one-and-a-half million people in this age group. By 2033, it is estimated that 23 per cent of the population will be aged 65 and over.[1]

The number of people in residential care homes is also growing rapidly and it is likely that this need for long-term care will continue to increase. The Government census carried out in 2001 found that 440,000 people in Britain are living in communal care home establishments, of which the majority live in residential care homes or nursing homes. The average age of care home residents is 85 years.[2]

A national contract to enable community pharmacists to advise residential care homes was introduced in 1989. This meant that community pharmacists who have completed the appropriate training could be paid by the NHS to provide pharmacy services to care homes that requested them.[3]

With the introduction of the new pharmacy contract in 2004,[4]

however, these services were reclassified as enhanced services, which meant that pharmacists who wished to offer them had to negotiate payment with the local primary care organisation.

The contractual framework says: “The pharmacy will provide advice and support to the residents and staff within the care home, over and above the dispensing essential service, to ensure the proper and effective ordering of drugs and appliances and their clinical and cost effective use, their safe storage, supply and administration and proper record keeping.”[5]

This appears to place the responsibility for safe supply on the pharmacist providing the service rather than on the care home management. Despite that, care home services were one of the 10 local enhanced services with the highest provision in 2006–07.[6]

In 2006, the Commission for Social Care Inspection (CSCI) published a report that examined the performance of care homes in relation to the National Minimum Standards (NMS). The report revealed that “nearly half of all nursing and care homes in England failed to meet the NMS for the handling of medicines. 12 per cent of care homes completely failed to meet standards, 43 per cent almost met standards and 44 per cent of care homes met the minimum standards.”

- The key failures identified by the CSCI inspectors were:[7]

- Failings in medicines administration to residents

- Failure in training before staff were expected to administer medicines

- Poor record keeping

- Poor systems in place for administering medicines

- Poor management of Controlled Drugs, especially morphine

- Poor management of medicines that should be administered when required

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has identified eight core principles[8]

of safe and appropriate handling of medicines in social care settings. They are:

- People who use social care services have freedom of choice in relation to their provider of pharmaceutical care and services, including dispensed medicines

- Care staff know which medicines each person has and the social care service keeps a complete account of medicines

- Care staff who help people with their medicines are competent

- Medicines are given safely and correctly, and care staff preserve the dignity and privacy of the individuals when they give medicines to them

- Medicines are available when the individual needs them and the care provider makes sure that unwanted medicines are disposed of safely

- Medicines are stored safely

- The social care service has access to advice from a pharmacist

- Medicines are used to cure or prevent disease, or to relieve symptoms, and not to punish or control behaviour

The purpose of this study was to examine which services care home managers access and how they rate the service provided.

Method

In 2006, a pilot study was conducted by self-administered questionnaires that were sent to 65 care homes in England. As a result of this study, the questionnaire was improved and it was decided to direct the questionnaires specifically to managers of care homes for the elderly. Subsequently, in 2007, questionnaires were sent to 2,000 managers of care homes for the elderly in four regions of England: the south west, midlands, home counties and the north. The homes were identified using the CSCI database of care homes. Only those classified as “elderly residential” were included in the study. In each region, the first 500 homes identified were sent a questionnaire. (A copy of the questionnaire is available from the author.)

Respondents were asked what type of care home they managed and the type of pharmacy providing the service. They were also asked about the frequency of visits by the pharmacist.

A list of possible services offered by community pharmacists was provided and respondents were asked to indicate which services they accessed and to rate them on a five-point Likert scale. Finally, the respondents were asked to provide an indication of their overall level of satisfaction with the services provided by the pharmacy with space for comments where appropriate.

Results

Completed questionnaires were received from 1,062 care homes (53.1 per cent). Most of the homes were privately owned (75 per cent), with 15 per cent being local authority run and 10 per cent being run by charitable organisations.

When asked specifically, overall satisfaction expressed by the managers of the homes was highest in the charitable homes, with 95 per cent of respondents indicating that they were very or fairly satisfied. Similarly, 93 per cent of managers of privately run homes expressed a high level of satisfaction. In the local authority homes, this figure was lower (75 per cent). Respondents were asked to indicate the type of pharmacy that provided the service from a choice of large multiple, supermarket pharmacy, independent or other.

Of the pharmacies cited as providing services, 624 (59 per cent) were large multiples and 410 (39 per cent) were independent with only 28 (3 per cent) coming under other categories, such as supermarket or GP surgery-owned.

Two hundred and seventy-eight respondents (68 per cent) were very satisfied and 108 (26 per cent) were fairly satisfied with the overall service provided by independent pharmacies whereas, of the 624 respondents accessing services from multiple pharmacies, 365 (58 per cent) were very satisfied and 210 (34 per cent) were fairly satisfied.

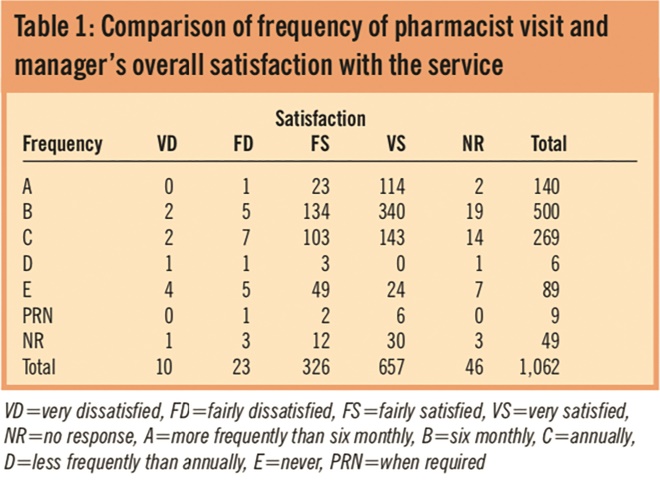

Overall satisfaction with the service was compared with the frequency of the pharmacist’s visit (Table 1). No significant difference was found (chi-squared test, P=0.8).

Table 1. Comparison of frequency of pharmacist visit and manager’s overall satisfaction with the service

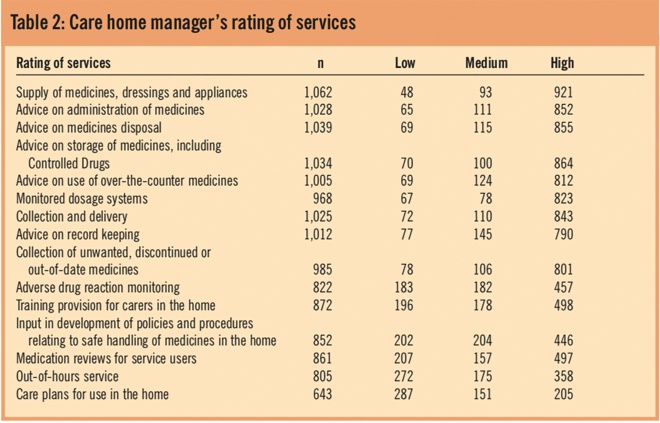

Care home managers were asked to detail the services they received from the pharmacy and to rate them on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 was very poor and 5 was very good. The results are shown in Table 2 in which a rating of 1 or 2 is shown as “low”, a rating of 3 is shown as medium and a rating of 4 or 5 shown as “high”.

Table 2. Care home manager’s rating of services

The most commonly accessed services were the supply of medicines, dressings and appliances, advice on the storage and disposal of medicines and collection and delivery services. Over 96 per cent of respondents accessed these three services.

The least commonly accessed service was the provision of care plans for use in the home, which was used by 60 per cent of respondents. Respondents were also asked if there were any additional services that they would like to receive. Some of the requests were for services that pharmacists were unable to provide, such as podiatry, but the most common response was for the provision of an out-of-hours service for urgently needed medicines.

Discussion

Care home managers were generally satisfied with the overall service they receive from their pharmacists. This level of satisfaction is not affected by the type of pharmacy providing the service or by the frequency of visits to the home by the pharmacist, although the contractual framework requires that visits are at least every six months.[5]

Services that could be improved include the provision of medicine supply outside of the normal pharmacy working hours and better staff training. A lack of care home staff training was highlighted in the CSCI report[7] and this is an area in which pharmacists could provide a valuable service. This would have financial implications for the pharmacist but funding is available through Government agencies, such as the Skills for Care and Train to Gain initiatives.[9]

Another service that showed a lower level of satisfaction was the provision of care plans. This is an area that could be developed jointly between pharmacists and carers in conjunction with regular medicines use reviews for residents.

Conclusion

The results from this study complement the observations from a recent study by Barber et al,[10]

who, in a multi-area survey, found that 69.5 per cent of patients in care homes were subject to at least one medication error during the study period and that errors occurred at all stages of the medication process (prescribing, monitoring, dispensing and administration).

The study highlighted lack of medicines training, medicines management and the need to appoint a pharmacist to take responsibility for the latter in a home or group of homes. Results from the present study indicate that many care home managers would welcome greater pharmacy input.

About the authors

Peter Clark, MRPharmS, is senior lecturer in pharmacy practice at the University of Portsmouth.

Dinesh Bolaky, Deborah Ferrigan, Ronak Patel and Dalprit Virdee were fourth year pharmacy students at the University of Portsmouth.

Correspondence to: Peter Clark (e-mail peter.clark@port.ac.uk)

References

[1] Office for National Statistics. Mid year population estimate. Available at www.statistics.gov.uk (accessed 21 January 2010).

[2] Office for National Statistics. Focus on older people 2005 Edition. Available at www.statistics.gov.uk.

[3] Somerville H. Pharmacy services for the elderly in residential and nursing homes. The Pharmaceutical Journal 1997;259:683–5.

[4] The new contract for community pharmacy. London: Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee; 2004.

[5] NHS Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework. Care home (support and advice on storage, supply and administration of drugs and appliances). London: Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee; 2005.

[6] Department of Health. Pharmacy in England. building on strengths — delivering the future. London: Department of Health; 2008

[7] Handled with care? Managing medication for residents of care homes and childrens homes — a follow up study. London: Commission for Social Care Inspection; 2006.

[8] The handling of medicines in social care. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2007.

[9] Siggers B. Access to funding for training. United Kingdom Care Home Association; 2009.

[10] Barber ND, Alldred DP, Raynor DK, Dickinson R, Garfield S, Jesson B. Care homes’ use of medicines study: prevalence, cause and potential harm of medication errors in care homes for older people. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2009;18:341–6. Available at qshc.bmj.com (accessed 21 January 2009).