Abstract

Objectives

To examine published evidence of a potential interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), determine the significance of the interaction and make recommendations regarding the impact of the interaction on clinical practice.

Method

We performed a MEDLINE literature search using OVID and PubMed (from 1950 to May 2009). Search terms used were proton pump inhibitors, clopidogrel, omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole. All articles published in English describing an interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs were included. The bibliographies of identified articles were reviewed for additional citations.

Discussion

The evidence suggests that the combination of clopidogrel and PPIs results in a reduction in antiplatelet activity. The strongest evidence for an interaction exists for omeprazole and lansoprazole. Combining a PPI with clopidogrel has been shown to increase the risk of recurrent myocardial infarction, stroke and death. An increase in adverse clinical outcomes has been demonstrated for all PPIs. However, this clinical evidence comes from retrospective studies. It would seem prudent to minimise the combination of PPIs with clopidogrel by using H2-receptor antagonists in place of PPIs wherever possible.

For patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) managed medically or using a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), clopidogrel has been proved to reduce atherothrombotic events.1 Patients treated with clopidogrel often have varying responses. At steady state, clopidogrel normally inhibits 40–60% of platelet aggregation, but some patients experience less platelet inhibition than this; they are termed “non-responders”.2 One meta-analysis found that 21% of patients undergoing PCI do not respond to clopidogrel and may be at increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) events.3 One recently proposed mechanism for clopidogrel non-responsiveness is an interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), resulting in decreased platelet inhibition.

Clopidogrel is an antiplatelet agent that causes non-competitive, irreversible inhibition of the P2Y12 receptor on the surface of platelets. Inhibition of this receptor blocks adenosine diphosphate (ADP) from binding and activating glycoproteins IIb and IIIa, thus preventing platelet aggregation.1,4 Clopidogrel is rapidly absorbed after oral administration and undergoes biotransformation by several cytochrome P450 isoenzymes in the liver, including 1A2, 2B6, 2C9, 2C19, 3A4 and 3A5.4,5 Studies have suggested that the 2C19 isoenzyme is a major requirement for biotransformation to the active metabolite, evidenced by a reduction in the area under the curve (AUC) of clopidogrel’s serum concentration-time graph for patients with a CYP 2C19 polymorphism.5,6

For patients who have experienced atherothrombotic events, PPIs can be used to prevent bleeding from pre-existing gastric ulcers or to prevent the formation of new ulcers caused by antiplatelet therapy.7,8 All PPIs are metabolised to some extent by CYP 2C19 and 3A4. Omeprazole is not only metabolised by 2C19 but also competitively inhibits it with a 10-fold greater affinity than for the 3A4 isoenzyme.7,9

Following the results of several studies that alluded to a possible drug interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs, two large regulatory and professional organisations issued position statements. In May 2009, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) in the US recommended that prescribers consider using an H2-receptor antagonist or an antacid instead of a PPI for post-stent patients who were prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy. For patients who require treatment for a gastrointestinal condition, the SCAI suggested that the cardiologist should discuss alternatives to a PPI with the patient’s primary care provider.11 In November 2009 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stipulated a change to the summary of product characteristics for clopidogrel to include a statement about a drug-drug interaction between clopidogrel and omeprazole and esomeprazole citing a reduced efficacy when clopidogrel is combined with these medicines.10

This research examines the data surrounding the proposed drug interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs. This includes data examining the pharmacodynamic interaction (ie, measured platelet function testing) as well as data assessing the clinical outcomes of combining clopidogrel with PPIs. We will then formulate the data into recommendations for clinical practice.

Literature review

A MEDLINE literature search using OVID and PubMed (from 1950 to May 2009) was conducted using the search terms: proton pump inhibitors, clopidogrel, omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole. The bibliographies of identified articles were then reviewed for additional pertinent citations.

Pharmacodynamic studies

The pharmacodynamic data demonstrate an inconsistent interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs. In these studies, the combination of clopidogrel with omeprazole or lansoprazole demonstrated a reduction in antiplatelet activity, presumably from a decrease in the clopidogrel active metabolite due to an inhibition of CYP 2C19 activation.12–14 Interestingly, there was no interaction noted between clopidogrel and esomeprazole or pantoprazole, suggesting this may not be a class effect.15 These conclusions are not completely supported by the outcomes studies presented below.

Outcome studies

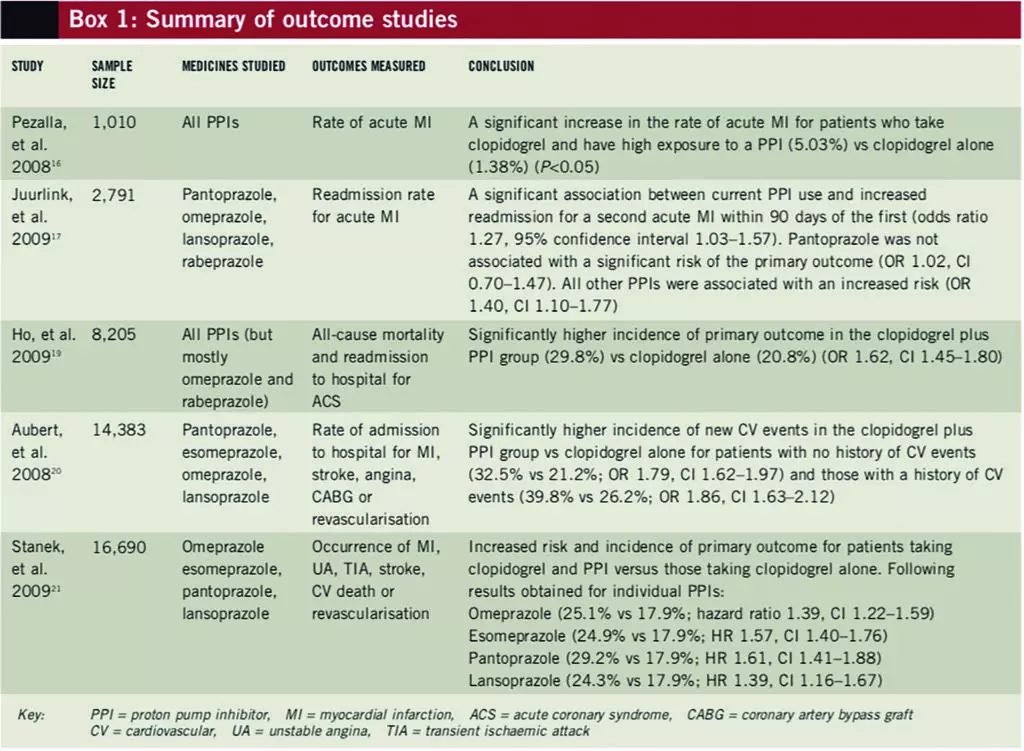

Numerous data assessing the clinical outcomes of using clopidogrel with PPIs have become available in recent years (see Box 1). These studies have been well designed but are all limited by the fact that they are retrospective cohort studies. The two most recent studies (at the time of writing) were only available in abstract form.

In response to the OCLA trial,13 the clinical impact of the interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs was examined by Pezalla et al, who studied the rate of acute myocardial infarction (MI) rate using medical and pharmacy databases from the US.16 Patients aged 65 years or less, who were determined to adhere with clopidogrel therapy, were divided into groups by PPI exposure levels based on their adherence rates: no exposure (n=384); low exposure (n=90); or high exposure (n=536). The rate of acute MI over the one-year study period was 1.38% in the control (ie, no exposure) group, 3.08% in the low PPI exposure group and 5.03% in the high PPI exposure group (P<0.05 for high exposure vs control). Although the high PPI exposure group had a greater number of patients with hypertension and diabetes, and overall had a greater severity of illness, the results remained significant when a subset of patients with similar comorbidities were analysed (P<0.05). This first attempt to examine the clinical outcome of the PPI-clopidogrel interaction exposed the possibility of it having clinical consequences.

Juurlink et al

Another study examined the interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel among older patients discharged from hospital after an acute MI.17 Records were reviewed for 13,636 Ontario residents, aged Δ66 years, who were discharged between 1 April 2002 and 31 December 2007 after an acute MI who had a prescription for clopidogrel dispensed within three days of discharge. Patients were followed up for a maximum of 90 days or until they were readmitted with another acute MI. The 734 patients who died or were readmitted were matched to one or more of the 2,057 controls for age, receipt of PCI, date of discharge and probability of short-term mortality. PPI use was categorised according to date of readmission as current (within 30 days of readmission), previous (within 30–90 days of readmission) or remote (within 90–180 days of readmission).

A significant association existed between the current use of a PPI and readmission for acute MI within 90 days (odds ratio 1.27, 95% confidence interval 1.03–1.57) compared with a more remote history of PPI use. The same association was not significant for those taking pantoprazole, or an H2-receptor antagonist, or for those not treated with clopidogrel. Treatment with other PPIs (omeprazole, lansoprazole and rabeprazole) was associated with reinfarction (OR 1.40, CI 1.10–1.77). The risk of death was not increased significantly by PPI use.17

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design and a failure to evaluate patient adherence, ethnicity (ie, genetic polymorphisms), concomitant drugs (eg, CYP 2C19 inducers) and risk factors for cardiovascular events.18 Imbalances in important comorbid disease states (ie, diabetes mellitus and congestive heart failure) were also present between matched cases. Other limitations include possible miscoding of acute MIs or misclassifications of PPI exposure due to intermittent use.17 Despite these limitations, this was a large, well designed attempt at examining the interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel.

Ho et al

A retrospective cohort study evaluated the risk of adverse outcomes associated with the use of clopidogrel with or without a PPI following ACS — comparing the rates of all-cause mortality and readmission to hospital.19 Data were collected as part of the “Cardiac care follow-up clinical study”. A total of 5,244 patients (63.9%) were prescribed a PPI (either at discharge, during follow-up or both) and 2,961 patients (36.1%) were not prescribed a PPI. Death or readmission to hospital to treat ACS occurred in 20.8% of patients in the clopidogrel only group compared with 29.8% in the clopidogrel and PPI group (OR 1.62, CI 1.45–1.8). Readmission for ACS in the clopidogrel only group occurred in 6.9% of patients compared with 14.6% of patients in the clopidogrel and PPI group (OR 2.29, CI 1.95–2.69). Revascularisation procedures were performed in 11.9% of patients in the clopidogrel only group compared with 15.5% of patients in the clopidogrel and PPI group (OR 1.38, CI 1.19–1.55).

Omeprazole, prescribed for 59.7% of patients, was associated with a risk for adverse outcomes with clopidogrel compared with no PPI treatment (OR 1.24, CI 1.08–1.41). (This study did not assess over-the-counter omeprazole use.) Rabeprazole was prescribed in 2.9% of patients and was also associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes with clopidogrel (OR 2.83, 95% CI 1.96–4.09). Data for other PPIs were limited due to low levels of use. Other limitations included that the study group consisted primarily of male ex-servicemen and no data corresponding with admission to other hospitals were included.19

Nonetheless, the trial confirmed the presence of an interaction between clopidogrel and omeprazole. Unfortunately there were not enough data regarding other PPIs to draw class-wide conclusions.

Aubert et al

The national (US) Medco integrated database was searched to investigate the effect of PPIs on clopidogrel’s efficacy at preventing coronary artery stent restenosis in a retrospective, cohort manner (at the time of writing, this study was only available in abstract form).20 Records were reviewed of patients who underwent stent placement during a one-year period between 2005 and 2006, received clopidogrel at the time of the operation and were at least 80% adherent with clopidogrel treatment for the following year. The incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (ie, admission to hospital for stroke, MI, angina, coronary artery bypass graft or repeat revascularisation) were compared for 4,521 patients taking clopidogrel and a PPI versus 9,862 patients taking clopidogrel alone. Patients received pantoprazole, esomeprazole, omeprazole or lansoprazole for at least nine months.

Patients with no history of cardiovascular events who were taking clopidogrel and a PPI had a higher incidence of subsequent major cardiovascular events (measured after one year) compared with those taking clopidogrel alone (32.5% vs 21.2%; OR 1.79, CI 1.62–1.97). For patients who did have a history of cardiovascular events, this effect was even larger (39.8% vs 26.2%; OR 1.86, CI 1.63–2.12). This investigation confirmed the detrimental clinical outcomes of combining clopidogrel with PPIs, but does not differentiate the information with regard to the individual medicines.

Stanek et al

The examination of the Medco database was expanded further in an abstract presented at an SCAI meeting in April 2009.21 This study examined the effect of individual PPIs on the clinical outcomes of patients treated with clopidogrel. The records of 16,690 patients, who adhered with clopidogrel therapy following coronary stenting, were examined. The primary endpoint was the occurrence of a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE; ie, MI, unstable angina, transient ischaemic attack/stroke, coronary revascularisation or cardiovascular death) over one year following the operation.

The occurrence of MACE was higher in the 6,828 patients taking a PPI compared with the 9,862 patients who were not (25.1% vs 17.9%; hazard ratio 1.51, CI 1.39–1.64). Four individual PPIs — omeprazole (n=2,307), esomeprazole (n=3,257), pantoprazole (n=1,653) and lansoprazole (n=785) — had sufficient data to detect a 25% increase in the incidence of MACE at one year. Each of the four was associated with an increased risk and incidence of MACE (compared with no PPI):

- Omeprazole (25.1% vs 17.9%; HR 1.39, CI 1.22–1.59)

- Esomeprazole (24.9% vs 17.9%; HR 1.57, CI 1.40–1.76)

- Pantoprazole (29.2% vs 17.9%; HR 1.61, CI 1.41–1.88)

- Lansoprazole (24.3% vs 17.9%; HR 1.39, CI 1.16–1.67)

The sample size was not sufficient to examine the effect of rabeprazole. This investigation demonstrates a class-effect for the PPIs with regard to an interaction with clopidogrel. Pantoprazole was no longer excluded from the implicated medicines.

Conclusion

Several studies have indicated that clopidogrel is a prodrug that is converted to its active form mainly by CYP 2C19. All PPIs are metabolised to some extent by CYP 2C19 and several inhibit it. Three pharmacodynamic studies and four outcome studies have shown that combining clopidogrel with a PPI can attenuate its antiplatelet activity. Omeprazole has been cited as the worst offender in two pharmacodynamic studies and one outcome study. Pantoprazole demonstrated the least reduction in antiplatelet activity in the pharmacodynamic studies. However, a recent analysis demonstrated that when used in combination with clopidogrel, pantoprazole’s risk of increased negative cardiac outcomes was no less, and possibly more, than other PPIs.21

The interpretation of the data presented here is difficult due to the major limitations of the studies. All of the outcome studies are retrospective and therefore not optimal. Another quandary regarding the available data is that patients on a PPI tend to be sicker and might have more risk factors for an adverse cardiac event.22,23 Even so, based on the current information, it is safe to conclude that patients on clopidogrel should not be put on a PPI routinely.11,22.23

Prasugrel is now available for the reduction of thrombotic cardiovascular events (including stent thrombosis) in patients with ACS who are to be managed with a PCI.24 Prasugrel has been shown to have a more consistent platelet response than clopidogrel and is less reliant on CYP 2C19 for its activation.2,5,12,24 Its place in therapy is yet to be defined but it may offer an alternative for patients who do not respond to clopidogrel — either due to a drug-drug interaction or a genetic polymorphism.

Options for patients who are taking clopidogrel and need gastroprotective therapy (eg, those at risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, ulcers or reflux disease) might include using an H2-receptor antagonist (eg, ranitidine 150mg twice a day, famotidine 20mg twice a day or nizatidine 150mg twice a day — doses might need to be reduced if the patient has renal impairment). Ranitidine has been found not to effect the platelet inhibitory actions of clopidogrel.25 Furthermore, H2-receptor antagonists have demonstrated no change in patient outcomes when combined with clopidogrel.21

For patients who require a PPI, a thorough risk-benefit analysis should be undertaken. Avoidance of omeprazole, since it is an inhibitor of CYP 2C19 rather than simply a substrate, would be one strategy. Another approach would be to take the PPI in the morning and clopidogrel in the evening; this allows for clearance of the PPI before clopidogrel is taken. This approach is not advocated in the FDA’s position statement.

Another option could be to use an increased dose of clopidogrel in patients who need to take a PPI. However, this concept has not been studied and should not be undertaken without sufficient antiplatelet activity monitoring.

About the authors

Allison Thompson is a resident pharmacist at The University of Chicago Medical Centre, Illinois, US.

Andrew Smith is clinical assistant professor for the division of pharmacy practice and administration at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, US.

Email: smithandr@umkc.edu

References

- Summary of product characteristics for Plavix (clopidogrel). Last updated August 2009. www.emc.medicines.org.uk (accessed 4 March 2010).

- Siller-Matula J, Schror K, Wojta J, et al. Thienopyridines in cardiovascular disease: focus on clopidogrel resistance. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2007;97:385–93.

- Snoep JD, Hovens MM, Eikenboom JC, et al. Clopidogrel nonresponsiveness in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Heart Journal 2007;154:221–31.

- Savi P, Pereillo JM, Uzabiaga MF, et al. Identification and biological activity of the active metabolite of clopidogrel. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2000;84:891–6.

- Brandt JT, Close SL, Iturria SJ, et al. Common polymorphisms of CYP2C19 andCYP2C9 affect the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic response to clopidogrel butnot prasugrel. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2007;5:2429–36.

- Hulot JS, Bura A, Villard E, et al. Cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-functionpolymorphism is a major determinant of clopidogrel responsiveness in healthy subjects.Blood 2006;108:2244–7.

- Blume H, Donath F, Warnke A, et al. Pharmacokinetic drug interaction profiles ofproton pump inhibitors. Drug Safety 2006;29:769–84.

- Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensusdocument on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on clinical expert consensus documents. Circulation 2008;118:1894–909.

- Li XQ, Andersson TB, Ahlstrom M, et al. Comparison of inhibitory effects of the proton pump-inhibiting drugs omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole on human cytochrome P450 activities. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2004;32:821–7.

- Food and Drug Administration. Information for Healthcare Professionals: Update to the labeling of clopidogrel bisulfate (marketed as Plavix) to alert healthcare professionals about a drug interaction with omeprazole (marketed as Prilosec and Prilosec OTC). November 2009. www.fda.gov (accessed 4 March 2010).

- Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. SCAI statement on: “A national study of the effect of individual proton pump inhibitors on cardiovascular outcomes in patients treated with clopidogrel following coronary stenting: the clopidogrel Medco outcomes study”. www.scai.org (accessed 4 March 2010).

- Small DS, Farid NA, Payne CD, et al. Effects of the proton pump inhibitor lansoprazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel and clopidogrel. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2008;48:475–84.

- Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2008;51:256–60.

- Sibbing D, Morath T, Stegherr J, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors on the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2009;101:714–9.

- Siller-Matula JM, Spiel AO, Lang IM, et al. Effects of pantoprazole and esomeprazole on platelet inhibition by clopidogrel. American Heart Journal 2009;157:148 e1–5.

- Pezalla E, Day D, Pulliadath I. Initial assessment of clinical impact of a drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2008;52:1038–9.

- Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, et al. A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ 2009;180:713–8.

- Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 2009;301:937–44.

- Aubert RE, Epstein RS, Teagarden JR. Proton pump inhibitors effect on clopidogrel effectiveness: the clopidogrel Medco outcomes study (abstract 3998). Circulation 2008;118:s815.

- Stanek EJ, Aubert RE, Flockhart DA, et al. A national study of the effects of individual proton pump inhibitors on cardiovascular outcomes in patients treated with clopidogrel following coronary stenting: the clopidogrel Medco outcomes study (abstract O–11). The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention Scientific Session, held in Las Vegas, Nevada, on 6–9 May 2009.

- Lau WC, Gurbel PA. The drug-drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ 2009;180:699–700.

- PPI interactions with clopidogrel. The Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics 2009;51:2–3.

- PPI interactions with clopidogrel revisited. The Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics 2009;51:13–4.

- Varenhorst C, James S, Erlinge D, et al. Genetic variation of CYP2C19 affects both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic responses to clopidogrel but not prasugrel in aspirin-treated patients with coronary artery disease. European Heart Journal 2009;30:1744–52.

- Small DS, Farid NA, Li YG, et al. Effect of ranitidine on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel and clopidogrel. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2008;24:2251–7.