Abstract

Aim

To identify any changes in pharmacists’ professional activities following participation in and completion of a postgraduate qualification.

Design

A quantitative study using a pre-piloted postal questionnaire consisting of closed and open questions as well as rating scales.

Subjects and setting

227 pharmacists who had completed a postgraduate qualification for community pharmacists or hospital pharmacists with the Department of Medicines Management, Keele University, between 1999 and 2002.

Results

131 questionnaires were returned and analysed (response rate 57.7%). A number of changes in professional activities were identified including an increase in the number and complexity of clinical interventions made by respondents. These were irrespective of whether the respondents had changed job. Respondents identified a number of activities they believed they would not be doing had they not completed a programme of postgraduate study. These included medicines management and providing prescribing advice. This appeared to be related to the clinical and communication skills that they identified as being the most useful skills derived from their qualification.

Conclusions

Postgraduate qualifications for community pharmacists and hospital pharmacists appear to have a positive impact on pharmacists’ professional activities. Postgraduate programmes must continue to evolve to provide for future developing needs.

There have been a number of developments within the NHS and the pharmacy profession that have provided many new opportunities for pharmacists over the past few years.1–12 These include:

- Primary care pharmacy

- Repeat dispensing schemes

- Advanced clinical roles

- Medicines management

- Public health roles

- Implementation of national service frame-works and National Institute for Healthand Clinical Excellence guidance

- Patient group directions

- Pharmacist prescribing

Relevant and timely postgraduate education and training that equips pharmacists with necessary knowledge, skills and competencies is required to enable them to realise these opportunities. A number of postgraduate courses in specific professional and clinical areas are available in the UK for pharmacists. During the past decade there has been a rapid expansion in the number of pharmacists undertaking formal, postgraduate clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice programmes.13 However, little is known about the impact that such courses have on pharmacists’ professional activities. Previously published studies suggest that postgraduate courses have a positive impact on practice for pharmacists and other health care professionals.14–17 Wilson and Wen14 found that, on average, respondents thought that the knowledge and skills obtained from a master’s degree in pharmacy administration had been useful in practice. The benefits most frequently cited by respondents were management skills, increased competence in areas of pharmacy business and the opportunity to advance their careers.

Bassan et al15 evaluated students’ and mentors’ perceptions and views of a diploma in hospital pharmacy management. They found that all students considered the content of the course to be useful in practice. All mentors believed that service benefits would result from students undertaking the course.

The impact of part-time post-registration degrees on the practice of nurses was evaluated by Hardwick and Jordan.16 Most respondents thought that their graduate skills were used in practice, with increased confidence, evidence-based practice, reflective practice and critical thinking being particularly cited. However, no specific examples of how practice had changed were given by respondents.

Wildman et al17 also found that higher education had a positive impact on nurses’ clinical practice. The skills respondents found to be most useful in practice were those not taught during their preregistration courses.

The aim of this study was to identify any changes in pharmacists’ professional activities following participation in and completion of a postgraduate qualification. The courses providing the qualification are delivered principally using distance learning media with some face-to-face contact on study days. There is an option to study for a one-year certificate or two-year diploma award. The development and assessment of clinical and professional knowledge and skills within practical experience is integral to all courses.18

Method

In January 2003, a 16-item pre-piloted postal questionnaire was sent from the principal researcher (JA) to 227 pharmacists who had completed a postgraduate certificate/diploma programme for community pharmacists (n=133) or hospital pharmacists (n=94) with the Department of Medicines Management, at Keele University between 1999 and 2002. The principal researcher was not involved in any course delivery. Pharmacists’ addresses were sourced from the then current edition of the Register of Pharmaceutical Chemists, not university records. A follow-up letter was sent to non-responders one month after the initial mailing.

The questionnaire consisted of both open and closed questions. Rating scales were used for some responses. Open questions gave participants the opportunity to comment freely on some aspects. The questionnaire was designed to identify:

- Why respondents chose to undertake the course

- Changes in job or job responsibilities and professional activities during or following completion of the course

- The perceived importance of the postgraduate qualification achieved to any employment changes

- Barriers to changing professional activities

- The most and the least useful aspects ofthe course in general

- Job satisfaction following completion ofthe course

This paper focuses on changes in job, job responsibilities and professional activities during or following completion of the course, and the importance of the postgraduate qualification to any changes. Specific extended role activities were not defined in the questionnaire. These were identified spontaneously by participants in their responses to relevant open questions and categorised accordingly.

The local multicentre research ethics committee was contacted regarding ethical approval for the study. It was subsequently confirmed that ethical approval was not required because the study population was derived from former students of the university and was not considered to come within the purview of research that required NHS Research Ethics Committee approval.

A quantitative approach to this study was employed for a number of reasons to address the research objectives. Being former distance learning students, subjects lived at widely dispersed locations across the UK thereby making a qualitative approach infeasible with the resources available. A postal questionnaire had the advantage of reaching a larger number of subjects and would also provide a broad perspective that could be explored in more depth in the future using qualitative methods. However, although a questionnaire was chosen to obtain the data for this study, it included open questions and rating scales to provide a qualitative aspect.

The results of the questionnaire were coded and stored in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Analysis of the results included descriptive statistics such as counts, means, standard deviation, percentages and two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. Responses to the open questions were grouped into themes for analysis. Quotes that expanded upon a particular theme or were found to be representative of a group of responses were selected for inclusion in the results.

Results

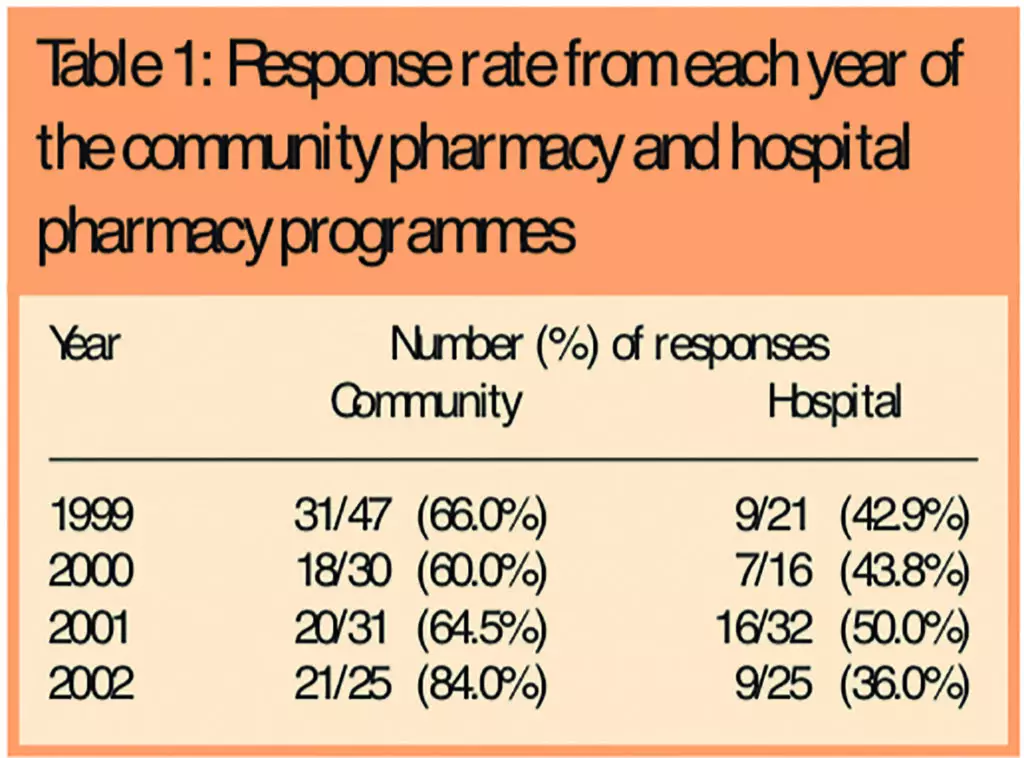

Response rate

One hundred and thirty-one questionnaires were returned and analysed (an overall response rate of 57.7 per cent). Twenty-four (18.3 per cent) were received after the second mailing. The response rate for pharmacists who had participated in the community pharmacy (CP) programme (90, 67.7 per cent) was greater than that for the hospital pharmacy (HP) programme (41, 43.6 per cent). The response rate from each year group is shown in Table 1.

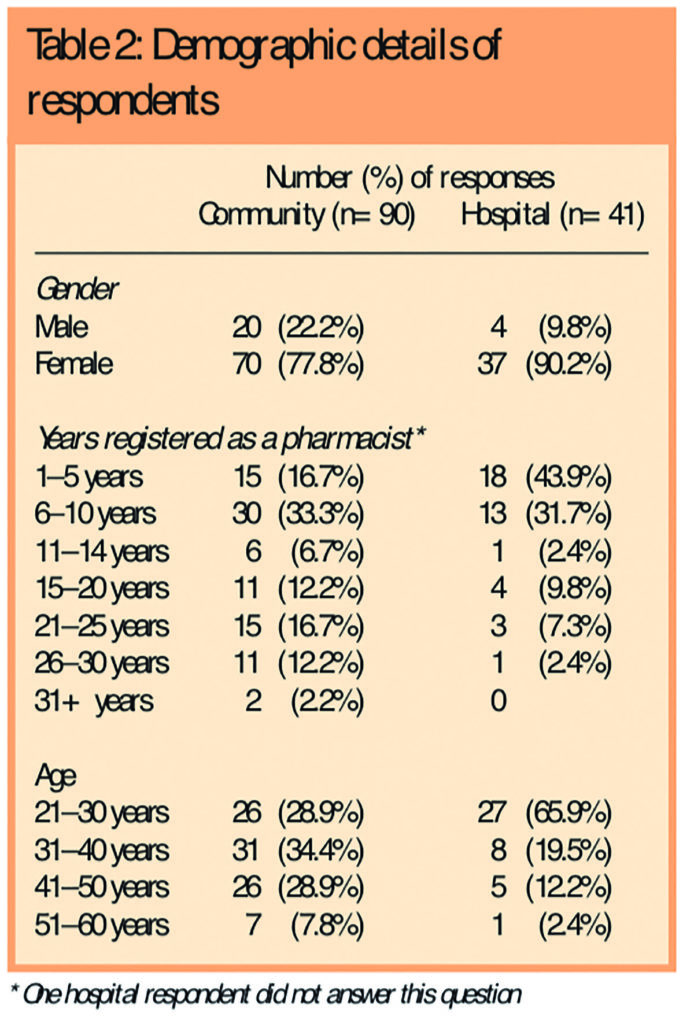

Demographic details

The demographic details of respondents are shown in Table 2.

Most respondents from both programmes were female. The questionnaire was posted to 99 females (74.4 per cent) and 34 males (25.6 per cent) from the CP programme and to 84 females (89.4 per cent) and 10 males (10.6 per cent) from the HP programme. This reflects the gender split of participants on these programmes in general. Respondents from the HP programme were generally younger and hence had been registered with the Royal Pharmaceutical Society for a shorter time. None of the respondents was aged over 60 years.

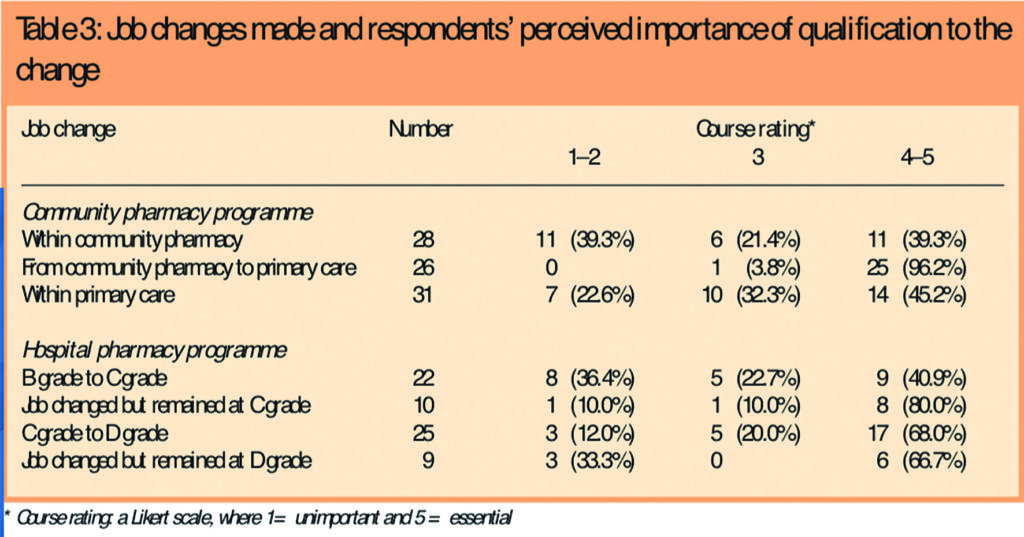

Job changes

A number of respondents indicated that they had changed job or pharmacy career path during or after completion of their course. This accounted for 56 CP respondents (62.2 per cent) and 37 HP respondents (90.2 per cent). Most of these respondents had changed job more than once. The number of respondents making at least two job changes was 34 CP respondents (60.7 per cent) and 27 HP respondents (65.9 per cent). The most common types of job change(s) made by CP respondents included a change where they remained within a community pharmacy environment and a change from a community pharmacy to a primary care environment; some had subsequently made further job changes within primary care. HP respondents generally tended to obtain higher work grades following a job change, although 19 respondents changing job remained at “C” or “D” grade. These changes are summarised in Table 3.

Respondents were also asked to rate how important they believed the qualification was for each of their job changes. This was assessed using a five-point Likert scale where “1” indicated unimportant and “5” indicated that the course was essential for that job change. These results are also shown in Table 3.

Changes in professional activities

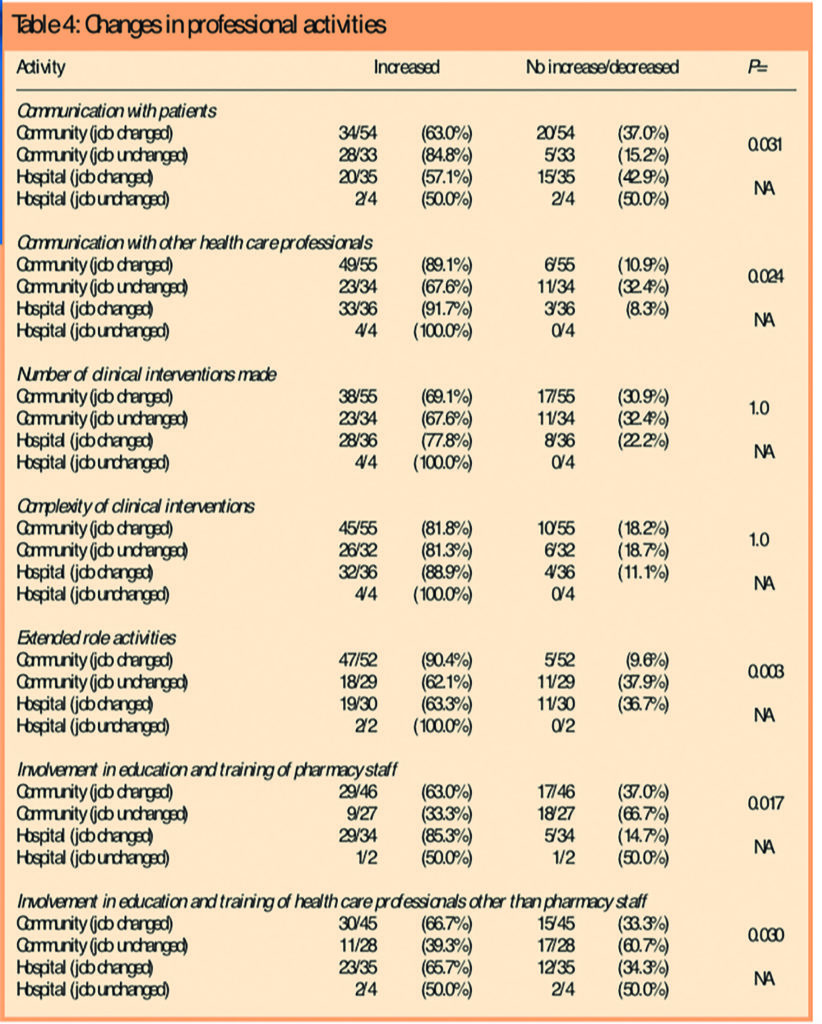

Respondents had been asked to identify how a series of professional activities had changed since participating in the relevant postgraduate programme. These activities included communication with patients and health care professionals, the number and complexity of clinical interventions, extended role activities, and education and training involvement with other pharmacists and health care professionals. Two-tailed Fisher’s Exact test was used to identify whether there was a statistically significant (P<0.05) difference in activities between CP respondents who had and had not changed job. Not all professional activities were relevant to all respondents. Those respondents who indicated that a particular activity was not relevant to them were excluded from the analysis. There was a statistically significant difference for all activities apart from the number and complexity of clinical interventions between these two groups (P=1.0 for both categories). The data are presented in Table 4. Statistical analysis was not used in relation to the data emerging from HP respondents since the lower number of responses from this group rendered statistical analysis inappropriate.

Communication activities

Most respondents from both postgraduate programmes indicated that their communication with patients had increased, irrespective of whether they had changed job. However, 20 CP respondents (37.0 per cent) who changed job thought that communication with patients had decreased or not changed. Most also expressed the view that their communication with other health care professionals had increased (Table 4). Respondents often cited confidence alongside communication:

I would not have had the confidence/tools to review patients’ medicines in a GP practice prior to the course. The skills helped with building bridges with prescribing advisers. — Primary care pharmacist

The course improved my confidence in my abilities, allowed me to communicate more effectively in assisting development of services within company. — Community pharmacy manager

The diploma gave me confidence to deal with other health care professionals. Since my employers were more involved with their GPs. I needed to be up-to-date and able to provide evidence to support my thoughts. — Community pharmacist

Clinical interventions

Respondents from both programmes indicated that the number and complexity of clinical interventions they made in their professional practice had increased (Table 4).

Extended role activities

Most respondents from both programmes who had changed job thought that their involvement in extended role activities had increased. This accounted for 47 CP respondents (90.4 per cent) and 19 HP respondents (63.3 per cent). For those who had not changed job, most believed that these activities had increased (Table 4). Medicines management activities (22, 24.4 per cent) and prescribing advice activities (29, 32.2 per cent) were specifically mentioned by CP respondents as activities that they now participated in as a result of completing the course, irrespective of having changed their job or not. A number of respondents described their extended role activities, often linking them with other behaviours and skills derived from the course such as confidence and communication:

More confident in taking part in extended role activities, eg, involved with provision of emergency hormonal contraception under a patient group direction. Prescribing advice — would not have had the confidence to get involved in this area. — Community pharmacy manager and prescribing adviser

I now attend preadmission clinics for cardiothoracic patients and give rehab talks to cardiac patients . . . the diploma gave me the confidence to do these activities — Hospital pharmacist (grade C)

Pharmacy services now include a smoking cessation clinic and training of GPs on the pharmacist’s role. I am also involved in a national medicines management services collaborative programme. I have also been involved in a diabetes screening trial and am currently preparing for a medicines clearout programme where patients are invited to return unused medicines for destruction and opportunities are taken to do simple medicines review where possible. — Community pharmacy manager

Involvement in education and training

Pharmacists’ involvement in education and training activities with other pharmacy staff (pharmacists, preregistration students, pharmacy technicians) and other health care professionals (medical staff and nurses) tended to increase for those respondents who had changed job.

With regard to training other pharmacy staff, 29 of those CP respondents who had changed job (63.0 per cent) indicated an increase in this activity compared with nine who had not changed job (33.3 per cent). Twenty-nine HP respondents who had changed job (85.3 per cent) identified these activities as having increased.

In relation to their involvement with the education and training of other health care professionals, 30 CP respondents who had changed job (66.7 per cent) thought that the training they provided to other health care professionals had increased. This was in comparison with 11 who had not changed job (39.3 per cent). Whether or not they had changed job, half or more hospital pharmacists who responded felt they provided more training to other health care professionals, and just over a quarter (11, 28.2 per cent) specifically mentioned that they would not have participated in such activities had they not completed the postgraduate programme (Table 4). One respondent described how the staff training element of her job had resulted in the transfer of the knowledge and skills she had gained on the course to others:

I now play a key role in developing health care staff. The outcome is that our team is educated to a much higher standard as evidenced in their performance with customers, questioning, responding to symptoms etc. — Community pharmacist

Course content

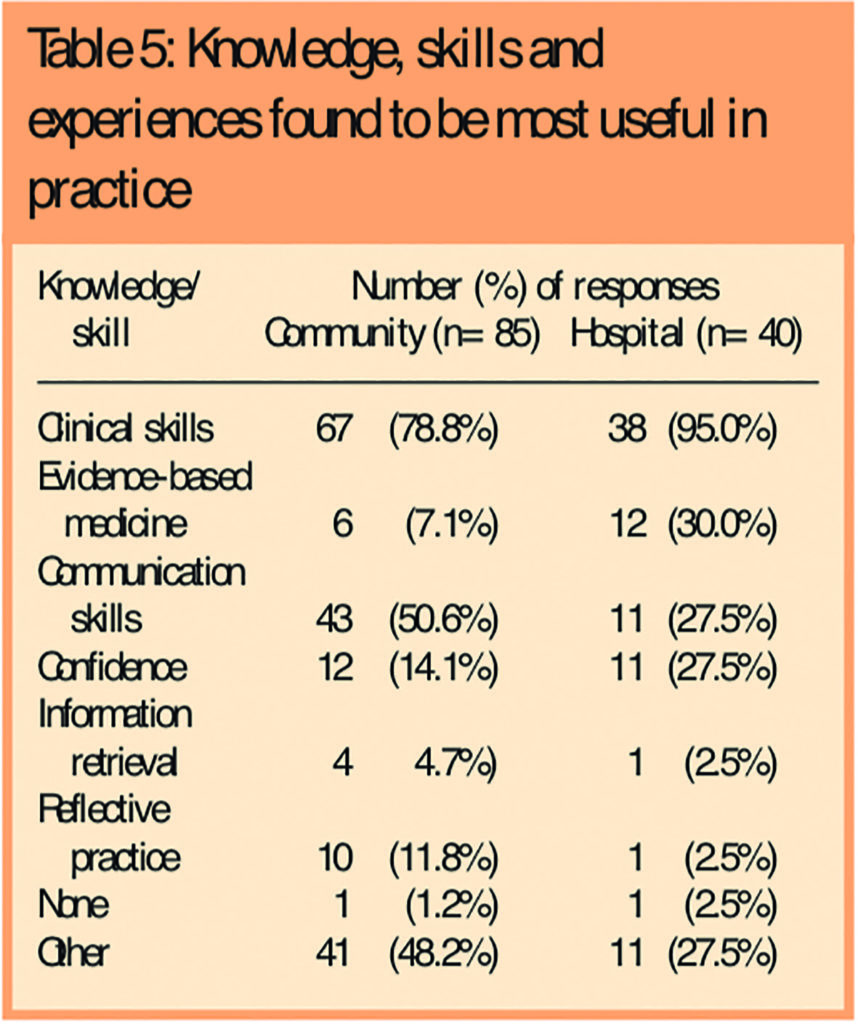

The knowledge, skills and experiences gained from the postgraduate programme, and identified as most useful by respondents for their daily practice, are shown in Table 5.

Respondents were invited to list as many as they thought relevant. The skill most frequently identified for both programmes was “clinical skills”, cited by 67 CP respondents (78.8 per cent) and 38 HP respondents (95.0 per cent). “Other” responses given by CP respondents included computer skills, time management, PACT analysis, clinical governance, audit, medication review and meeting other pharmacists. “Other” responses given by HP respondents included computer skills, problem solving, meeting other pharmacists and teamwork. Five CP respondents and one HP respondent omitted to answer this question.

Discussion

This study has identified a number of changes in professional activities, among pharmacists who completed a postgraduate qualification, that they felt they would not have achieved through their job alone. However, there are limitations to consider:

- The study was limited to former students of a single university department and therefore the results cannot be generalised to courses offered by other institutions

- The number of HP respondents was low, making comparisons with CP respondents difficult

- A control group of pharmacists without a postgraduate qualification was not included, thereby limiting the ability to infer that the postgraduate programmes were key to influencing any changes in respondents’ job, career or professional activities

- The study was retrospective and respondents may not have been able accurately to recall events or course content

- There may be a number of variables, not identified in the study, that may influence the professional tasks/activities and jobs of pharmacists, for example family ties and other qualifications held by respondents, the effects of the requirements of individuals’ jobs, individual continuing professional development and self-reporting in relation to identifying specific tasks or activities

An overall response rate of 57.7 per cent was achieved. The HP response was lower at 43.6 per cent. Six of the seven questionnaires that were returned unopened were from HP programme pharmacists. Changes in address due to the potential mobility of younger pharmacists from the HP programme may explain the lower response. The comparatively higher CP response (67.7%) provides reassurance that the results are representative for this sub-group. Although the response from the HP sub-group was adequate, the potential for less representative, biased data should be considered.

Most respondents from each course had changed job. This was particularly so in relation to HP respondents (90.2 per cent). Just over a third of CP respondents had not made any job changes. A number of reasons may explain these differences. First, hospital pharmacy has a well-established career structure and hospital salaries are generally lower than those of their community pharmacy colleagues, so promotion is required to achieve a higher salary. Indeed, 22 HP respondents (53.7 per cent) changed job from a basic “B” grade position to a more senior “C” grade. Community pharmacy does not have such a well established career structure. The starting salaries are higher and the incentive to gain promotion for higher pay may be less pronounced. Secondly, there was a difference in how long respondents had been registered with the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, with 16.7 per cent of CP respondents being registered for five years or less compared with 43.9 per cent of HP respondents. Recently qualified pharmacists in the first four years after registration are known to be a highly mobile group showing rapid career progression.19 These differences in career structure, salary and length of time registered may explain the higher number of HP respondents changing job.

A range of job changes were made by respondents from all courses. The most common types of job changes made by CP respondents were to remain as community pharmacists, change sector to a primary care role or make further job changes within primary care. Twenty-five respondents (96.2 per cent) rated the qualification as very important (rating 4) or essential (rating 5) for a job change from community pharmacy to a primary care position. However, the qualification was reported as less essential by those respondents taking on other positions within the same field of practice.

It is likely that when a pharmacist is first employed in a new area of practice, new knowledge and skills learnt on the course are being used. However, for subsequent job changes in the same field these skills are no longer new and the importance of the course may diminish with time along with respondents’ recollection of the course content. Most HP respondents rated the course as very useful or essential for most job changes.

The changes in professional activities described by respondents following postgraduate study may be linked to changes in the their jobs and career paths. There was a statistically significant difference in response between those CP respondents who had changed job compared with those who had not for most activities. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the number and complexity of clinical interventions. Both groups thought these activities had increased.

Although acknowledging the potential influence of an individual’s continuing professional development, it can be argued that the change in these activities is most likely a direct result of the effect of postgraduate study rather than a change in job or job responsibilities. This is consistent with the fact that “clinical skills” was the most frequently cited skill that respondents believed was the most useful in practice, which is in accordance with other studies where further qualifications had a positive impact on clinical practice.16,17

However, although Hardwick and Jordan found that nurses believed their graduate skills were used in practice, respondents were unable to quote any specific examples of how their practice had changed.16 They suggested that post-registration degrees may provide academic rather than clinical knowledge. This does not appear to be the case for this study since respondents cited a number of professional activities that require good clinical skills. These included medicines management, providing prescribing advice and making more complex clinical interventions.

Communication with patients and other health care professionals generally tended to increase, irrespective of a job change. This may be due to an increased confidence in their ability and skill as cited by many respondents. Twenty CP respondents (37.0 per cent), having changed jobs, found that their communication with patients had decreased or not changed. This may be explained by job changes from community pharmacy into primary care, a change made by 26 respondents, where contact with patients may be comparatively less, although it could be argued that communication with GPs would be expected to increase, particularly if they have a prescribing advice role.

Communication with other health care professionals may be influenced by a change in job. Those respondents employed in primary care or hospital pharmacy may find other health care professionals more accessible. Skills gained as a result of postgraduate study may have influenced communication with 43 CP respondents (50.6 per cent) and 11 HP respondents (27.5 per cent). HP respondents citing “communication skills” as one of the most useful skills gained from their postgraduate studies that could be applied in practice.

The normally higher accessibility of other members of the multidisciplinary health care team may account for comparatively fewer HP respondents choosing communication as one of the most useful aspects of the qualification.

Providing education and training to other pharmacy staff (pharmacists, preregistration students, pharmacy technicians) and other health care professionals (including nursing and medical practitioners) tended to increase for those respondents having changed job. This finding suggests that formal postgraduate study may be an important source of useful knowledge and skills that can not only be applied by the participant, but also have the potential to impact on other health care professionals who may benefit from the training provided by these pharmacists.

Most respondents from both programmes thought that they were more involved with extended role activities. The largest increase in extended role activities was for those respondents who had changed jobs. This could partly be explained by respondents moving to a primary care role where extended role activities such as providing prescribing advice are regularly practised.

CP respondents identified medicines management activities that they thought they would not be doing if they had not completed the postgraduate qualification. Medicines management activities are described in the new contractual framework for community pharmacy, for example, a medicines use review and prescription intervention service. Other enhanced services include medicines assessment and compliance support, patient group direction service and anticoagulant monitoring. All pharmacists should be able to adapt to practice in the new NHS. Due to the absence of a control group it was not possible to determine whether pharmacists who do not hold a postgraduate qualification would be undertaking these activities.

This study has highlighted some of the potential benefits of participation in a formal postgraduate programme that provides pharmacists with knowledge and skills that enable them to develop their clinical and professional practice to fulfil the expectations of modern pharmacy practice and the wider health care agenda in the UK. Postgraduate programmes for pharmacists must continue to provide relevant and up-to-date knowledge and skills related to the Government’s health strategies to ensure pharmacists are able to play an integral part in the delivery of health care. Duggan et al have also suggested that the development of postgraduate programmes should retain both usefulness and validity within professional practice rather than react to consumerist demands for career progression.13

This study has demonstrated that the programmes investigated were perceived by participants as being both useful and valid for professional practice. Respondents reported that they applied key knowledge, skills and experiences derived from their postgraduate qualification in their everyday practice.

Conclusion

This study has identified a number of changes in professional activities among pharmacists which they believed they would not be doing had they not participated in a formal postgraduate studies. These included an increase in the number and complexity of clinical interventions, and activities related to medicines management and providing prescribing advice — key activities for pharmacists practising in modern health care. Although the relationship between the requirements and content of an individual’s job and self-directed change is complex, this study provides new evidence that supports how change can potentially be affected by postgraduate study, irrespective of change in job.

This paper was accepted for publication on 12 January 2006.

About the authors

Jeff Aston, MSc, MRPharmS, is a hospital teacher practitioner pharmacist at New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton. At the time of the study he was senior pharmacist for elderly care at Good Hope Hospital NHS Trust. Pat Black, MAODE, MRPharmS, is senior lecturer and postgraduate courses development manager/director of postgraduate studies in the Department of Medicines Management at Keele University.

Correspondence to: Jeff Aston, Pharmacy Department, New Cross Hospital, Wednesfield Road, Wolverhampton WV10 OQP (e-mail jeff.aston@nhs.net).

References

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Pharmacy in a new age. Developing a strategy for the future of pharmacy. London: The Society; 1995.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Pharmacy in a new age. Building the future. A strategy for a 21st century pharmaceutical service. London: The Society; 1997.

- Department of Health. The new NHS — modern, dependable. London: The Department; 1997.

- Department of Health. A first class service, quality in the new NHS. London: The Department; 1998.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Achieving excellence in pharmacy through clinical governance. London: The Society; 1999.

- Department of Health. The NHS plan — a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: The Department; 2000.

- Department of Health. Pharmacy in the future — implementing the NHS plan. London: The Department; 2001.

- Audit Commission. A spoonful of sugar. Medicines management in NHS hospitals. London: The Commission; 2001.

- Department of Health. rThe NHS knowledge and skills framework (NHS KSF) and the development review process. London: The Department; 2004.

- Meadows N, Webb D, McRobbie, Antoniou S, Bates I, Davies G. Developing and validating a competency framework for advanced pharmacy practice. Pharmaceutical Journal 2004;273:789–92.

- Department of Health. A vision for pharmacy in the new NHS. London: The Department; 2003.

- Department of Health. The new contractual framework for community pharmacy. London: The Department; 2004.

- Duggan C, Dhillon S, Bates I. Developing postgraduate education that meets the needs of the profession. Pharmaceutical Journal 1999;263:949.

- Wilson JP, Wen LK. Influence of a non-traditional master’s degree on graduates’ career paths. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2000;57:2196–201.

- Bassan SS, Hynam BM, Marriott JF, Wilson KA. Specialised education in hospital pharmacy management: an evaluation of postgraduate student and host mentor attitudes. Hospital Pharmacist 2000;7:217–9.

- Hardwick S, Jordan S. The impact of part-time post-registration degrees on practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2002;38:524–35.

- Wildman S, Weale A, Rodney C, Pritchard J. The impact of higher education for post-registration nurses on their subsequent clinical practice: an exploration of students’ views. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1999;29:246–53.

- Postgraduate programmes information. Department of Medicines Management, Keele University. Available at www.keele.ac.uk/depts/mm/Education/pedu.htm (accessed 26 January 2006).

- Rees J, Clarke D. Employment, career progression and mobility of recently registered male and female pharmacists. Pharmaceutical Journal 1990;245(Suppl):R30.