Abstract

Aim

To describe the experiences of pharmacy staff with inpatient electronic prescribing (EP) systems.

Design

Telephone interview via a semi-structured questionnaire.

Subjects and settings

Pharmacy departments in UK NHS hospitals

Outcome measures

System features, changes to pharmacy services before and after introduction of EP, perceived advantages and disadvantages for staff and working practices and desired developments.

Results

Three different systems were in use in the seven hospitals contacted. Electronic prescribing was used in most inpatient wards, excluding high dependency wards. All systems had clinical decision support, usually maintained by pharmacy. All interviewees said there had been changes to pharmacy services after implementation, such as the way medicines were ordered, methods of stock control and clinical roles and responsibilities. Overall, electronic prescribing was seen as a benefit. Many tasks were identified as easier and more advantages were seen than disadvantages. Desired future developments mentioned were to use full clinical decision support, to add a formulary and to make documentation of allergy status mandatory. All interviewees felt that adequate training was important.

Conclusion

EP affects how pharmacy services are delivered. It needs considerable change and a multidisciplinary approach. This study highlights issues that need to be considered for successful implementation of EP.

By 2005, all acute hospitals in the UK were expected to have implemented electronic prescribing (EP) as part of the Government initiative to improve the treatment and care of NHS patients through application of information technology.1 This implementation deadline has passed, but it appears that few NHS trusts have moved beyond the pilot stage.2

Currently, prescribing in most NHS hospitals involves the use of paper charts for each patient, on which doctors handwrite and sign medication orders. Nurses use the same charts to record administration.

As a result, the widespread introduction of EP should be expected to change several aspects of clinical care in the NHS. It is, therefore, important that all professionals are aware of the possible impact of EP on the way they work.

Adoption of new methods for carrying out established tasks means that doctors, nurses and pharmacists, in particular, will need to change their routines and established relationships fundamentally.3 Implementation of these systems requires considerable organisational change, which healthcare staff can find threatening.

Electronic prescribing and the pharmacy service

EP in hospitals is expected to have a positive influence on safety, effectiveness, efficiency and the cost of providing clinical care.3 For pharmacy departments involved in implementing EP in their hospitals, it is important to understand the advantages and disadvantages, and how the system will alter ways of working.

Although traditional roles will change, there may be new responsibilities as a result of EP. In their 2003 survey of sites which piloted or implemented electronic prescribing and medication administration, Brennan and Spours found that pharmacists’ positions as part of multidisciplinary EP working groups were crucial in ensuring the robustness of the new prescribing process.4 Other roles include ensuring the system does not impact too greatly on the pharmacy workload and being responsible for the safe and effective use of the system within the remit of the pharmacy department.2

Published data on how EP has affected pharmacy services in the UK is lacking. In a comprehensive review of their experiences in Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust, Foot and Taylor argue that the area that had to change its working practices most was pharmacy. In their article, they discuss the impact of EP on their pharmacy, especially the benefits of the system and the use of clinical decision support (CDS).2

Published information on implementation and evaluation of EP (often used interchangeably with the term computerised physician order entry [CPOE]) from the US is plentiful.5–11 However, much of it is not applicable to the UK, especially within hospital pharmacy, where models of pharmacy practice and service delivery are often quite different.4 Barber et al (2007) evaluated the pilot implementation of an electronic prescribing and administration system on a surgical ward in a London teaching hospital.12 They also included views from pharmacists. Issues discussed ranged widely, including system functions, staff perspectives and organisational context. However, since the system was based on one ward, relevance to other sites and specialties cannot be assumed. This study was carried out to:

- Be able to describe how EP has changed the way pharmacy staff in UK hospitals work

- Establish the perceived advantages and disadvantages of EP and EP systems for a hospital or organisation

- Establish the benefits to pharmacy departments of changing from a manual system to an electronic system of prescribing

The findings will be of use to staff looking for practical information on pharmacy and EP in UK settings.

Method

The research method was interview-based via a semi-structured questionnaire. The interviews took place between March and April 2005. The local ethics committee confirmed that ethics approval was not required.

Questionnaire design

The themes and questions for investigation were chosen by discussion with colleagues and by searching for articles on Pharmline, Medline (1996 to date) and Embase (1996 to date). Keywords used included electronic prescribing, computerised physician/prescriber order entry (CPOE), physician/prescriber order entry, computerised order entry, health informatics, electronic medication administration record (EMAR) and computerised prescribing combined with clinical pharmacy, hospital pharmacy and pharmacist. Common themes were identified from the literature search and used to develop areas for investigation. We only studied electronic prescribing in inpatients. The questionnaire was piloted by telephone to one pharmacist at one hospital, which was piloting EP at the time. Modifications to the questionnaire were then made to clarify ambiguous questions to obtain the final version for the proper interviews.

Identification of hospitals

Hospitals that had implemented EP were identified from the literature search and anecdotally. Only those using EP for all or most of their inpatient prescribing were included.

Interviews

Each pharmacy department was telephoned and asked to identify the appropriate person to contact. This person was then sent both a letter and an e-mail explaining the aims of the study and inviting them to participate. Some respondents asked to see the questions beforehand. We recognised that this would help to ensure we were talking to the most appropriate person, and that the information we needed would be at hand during the interview. A list of questions was therefore sent separately to all interviewees. They were asked to confirm in writing their willingness to participate. Any contacts who had not replied within a week were followed up by telephone.

One member of staff from each hospital was interviewed by telephone. The length of interview varied between 45 and 90 minutes. Each telephone interview was recorded with permission from the interviewee and notes were taken contemporaneously.

Data analysis

Each recording was reviewed and missing information from interview notes added. All information was reported anonymously, with no identification of hospitals. Quantitative and qualitative data were analysed according to the themes in the questionnaire. MS Excel 2000 was used to arrange the data. Pilot data were not included in the final analysis.

Results

Seven UK hospitals in different trusts, were identified. Two were teaching hospitals. All agreed to be involved. All the staff interviewed were pharmacists who worked as part of the clinical service or were involved in the support or design of the EP system in their hospital.

Three hospitals used the Meditech system, two used the TDS 7000 system and two used the JAC system. The number of years that EP was used ranged from three to 16 years. All systems were commercially available.

Implementation of electronic prescribing

EP was used mainly for inpatients. Inpatient areas where it was commonly not used were intensive care, the high dependency unit, accident and emergency, and paediatrics.

Three hospitals stated that EP was piloted before roll-out to other areas. In each case, piloting took place on one ward. The pilot wards used varied from surgical wards, where there was a high turnover of both uncomplicated and complex cases with different clinical conditions, to orthopaedic wards, where the turnover was low. This is important as the software can be assessed for safety and stability at different levels.

Four hospitals mentioned that if they were to repeat the implementation process they would give more staff training beforehand. In only one hospital was a change made to pharmacy practice before the roll-out of EP. This involved making the technicians’ roles more ward-based.

Prescribing systems and processes

Five hospitals electronically recorded medicines administration in real time and the other two hospitals recorded the administration on paper and then added the information to the electronic system retrospectively. Hospitals that recorded the administration on paper first did not find this a problem, but accepted that it was not ideal.

In all hospitals doctors entered the prescription orders on to the system. One hospital also had pharmacists regularly entering prescribers’ orders. This hospital also had plans to give pharmacists primary responsibility for entering medicines orders in the near future. All except one hospital allowed full access to pharmacists to alter the drug regimens. The hospital that gave pharmacists no prescribing access were in the process of reviewing this.

Allergy documentation before a doctor could prescribe was mandatory at only one hospital. Three hospital systems had the option to select the allergy from a list, two hospitals could free-text the allergy and two hospitals had both these options. Some hospitals, although they had the same EP system, recorded allergies in different ways.

Only one hospital prescribed all medicines on the electronic system. Six hospitals still required the use of paper charts for prescribing drugs, such as insulin sliding scales, intravenous fluids, blood products, anticoagulants and medicines administered by continuous infusion. In four out of six hospitals it was possible to enter the drug and time of administration on the system, but still use paper charts for documenting doses prescribed and administered. In four hospitals, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and parenteral chemotherapy were also prescribed on paper.

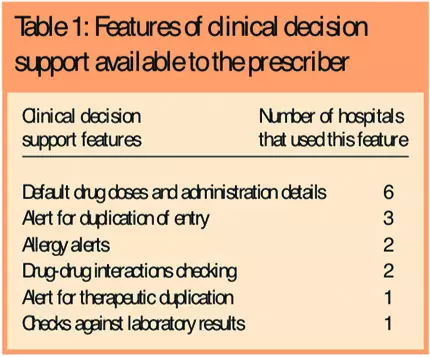

Two hospitals used a system with the option to restrict the choice of drugs that could be selected by the prescriber. The availability of products for prescribing was managed by pharmacy and introduced a level of formulary control. This was helped by the EP system being linked to the pharmacy stock system. The type of clinical decision support (CDS) available to prescribers varied (see Table 1).

In six of the hospitals the CDS was maintained by pharmacy. Two hospitals had an advanced prescribing system, which integrated treatment protocols and order sets.

Three hospitals used the EP system for pharmacists to communicate with other staff and document their contributions to the care of the patient. Two of these hospitals also used their systems to monitor clinical pharmacy activity by reviewing recorded information.

The pharmacy service

Since the implementation of EP, five sites had changed pharmacy service delivery. For example, more prescription screening was done from pharmacy, technicians identified the need for stock and dispensed items at ward level, and pharmacists had more clinical input on the wards, by attending more ward rounds.

Five hospitals stated that the time pharmacists spent on the ward had not changed. At three of the hospitals pharmacy staff were able to carry out more clinical activities without increasing the amount of time spent at ward level. In one of the two hospitals where time spent had changed, staff spent less time on wards and in the other the interviewee said that the change had varied with individuals.

Pharmacists at four hospitals visited all the patients daily whether they had a wireless or a fixed device system. At one hospital the charts were printed off and pharmacists carried these as they reviewed patients at the bedside. At the other three hospitals pharmacists only saw patients if queries about their prescriptions had been previously identified. Hospitals where pharmacists did not see their patients daily did not see this as a problem, as it allowed pharmacists to extend their clinical role by, for example, attending ward rounds. If pharmacies were short staffed, medicines prescribed could be reviewed from computer screens based in the dispensary. However, it was highlighted that remote screening of prescriptions reduced the contact time with patients, denying them the opportunity to ask questions or to be given expert advice on their medicines.

None of the EP systems needed pharmacy staff to endorse the drugs for supply. In four of the systems the computer was programmed to identify stock drugs. All the systems enabled pharmacy staff to indicate to the nurse whether the patient had their own medicines (patients’ own drugs — PODs) with them.

In six hospitals, orders for non-stock medicines were sent direct to the pharmacy electronically, in some cases at the point of prescribing. In four hospitals, a label was generated automatically, which would be used for dispensing in pharmacy. One hospital mentioned that technicians’ roles in the dispensary may become “devalued” if they are only dispensing against electronically generated labels.

Six hospitals found that EP had an impact on the dispensary. All found that prescriptions for discharge medication (to take away — TTAs) and inpatient items had quicker turnaround times as they were sent to the pharmacy electronically. Three hospitals indicated that the pharmacy workload had increased. The number of staff had generally not changed in hospitals after implementation of EP. In most cases only one extra staff member (pharmacist, technician or system manager) was needed to help implement and support the system.

Perceived advantages and disadvantages

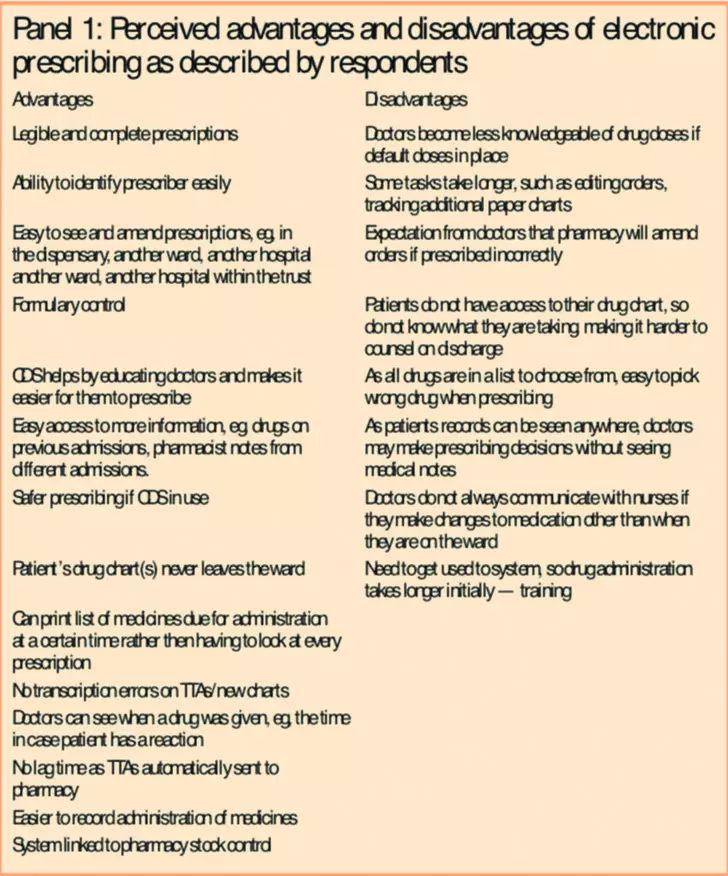

Interviewees thought there were few initial problems encountered when implementing the EP systems. The general issue that all hospitals mentioned was that adequate training and support is needed on implementation. Other perceived advantages and disadvantages are listed in Panel 1.

Three hospitals had audited some aspects of their system. The areas that were audited were the clinical decision support, completion of drug administration records by nurses, improvements in doctors writing prescriptions accurately and medication errors in prescribing and administration. All interviewees wanted to make some changes to their system to benefit pharmacy. For example: adding a formulary to the system; integrating hospital guidelines into prescribing; prescribing by pictures, especially for inhalers and insulins to help with identification during drug history taking; linking the system to the pharmacy stock system.

Discussion

Implementation

EP was generally not implemented in critical care areas in the hospitals surveyed. Foot and Taylor report that in their trust this was mainly due to the difficulties in setting up a programme to enable continuous infusions to be prescribed on their system.2 The training needed for successful implementation of an electronic prescribing system is something that should not be underestimated, and this is highlighted by the fact that many interviewees stated that they would have given more training before implementation. Published literature indicates that large hospitals with high staff turnover and frequent use of agency staff and locums will have significant training issues to deal with.4

Prescribing systems and processes

The recording of drug administration in real time was seen to be ideal. Brennan and Spours recommend that hospitals should consider having wireless portable technology to ensure that lists of drugs due are available in real time and are not out of date.3

This study found that, in general, order entry had not been delegated to pharmacists although most hospitals allowed pharmacists full access to alter the drug regimens. In the US, CPOE is recognised as a new skill and will be associated with a significant learning curve, which may give rise to new errors. As a result, there may be a view that pharmacists should be responsible for entering orders for physicians.13 However, not everyone believes that this is a progressive development.6 In the UK,Winchester Hospital believes that pharmacists are best placed to enter prescriptions and have incorporated clinical pharmacists on consultant ward rounds, where they are in a position to make drug changes, initiate therapy and transcribe TTAs.14

There was no consensus about documenting allergy status. Experience shows that ensuring documentation of allergy status is an area that is often difficult in manual systems.15 Electronic systems can ensure this information is always present on the prescription at the point of drug prescribing and administration.15–17 Where allergy completion is mandatory and CDS exists, the allergy alert feature will alert the prescriber if the patient is allergic to any of the drugs prescribed, allowing them to reconsider their choice.18 However, organisations should also remember that using CDS in this way may not be reliable if free text is allowed, because drug entries may be misspelt or not recognised by the system.

The clinical decision support provided by systems varied between hospitals. CDS systems have been shown to improve prescribing safety compared to paper prescribing.18,19 However achieving safety without overwhelming doctors with clinical alerts is essential for this system to be accepted.11,20

Electronic prescribing was used to facilitate formulary management in two hospitals. It is clear that if products that appear in drug dictionaries are specifically selected, the list of drugs available for prescribing can be limited to those that the hospital allows. Different areas and non-medical prescribers could be given access to a limited list of drugs. Literature from the UK and the US shows that it is possible to set up systems such that authorisation to prescribe restricted drugs must be sought before proceeding, or more information can be requested by the programme before the restriction is lifted.11,21

Brennan and Spours reported that integration of the pharmacy’s stock control system, while desirable, may not be essential during the early phases of implementation.4 Interviewees from the hospitals which linked EP to the pharmacy stock system stated that they used this to flag up drugs that were not in stock and where needed, restricted the prescribing of such drugs.2

Pharmacists were usually responsible for creating the drug databases from which the doctors prescribe and for maintaining them thereafter. The development and maintenance of the databases and their application to integrated care pathways and local guidelines will be a new and time-consuming role for clinical pharmacists in the future.22 Unfortunately, one of the barriers to this is the availability of appropriate software for the UK market.4

Recalling pharmacists’ communications and contributions is not easily done with paper records. EP was found to facilitate this through the use of electronic audit trails. Audit trails are portrayed in the literature as a significant benefit of EP as they ensure that everyone involved in the medicines process can be identified, from the doctor who prescribed, pharmacist who clinically checked the prescription right up to the nurse who administered it.2,16,23

The pharmacy service

It is widely believed that clinical pharmacists in hospitals that have EP spend more of their time on clinical duties and less time on stock control and record keeping, compared to other UK hospitals.17 Franklin et al’s report on the introduction of EP on one ward supports this.24 Although this has not been fully borne out by our study, the facility to view prescriptions from any terminal has enabled pharmacists to target patients who may need more pharmacy input, without having to visit the ward first. This may save time and can be especially useful when there are staff shortages. However, there may be an issue of reduced patient contact. By not reviewing drugs still prescribed on paper charts or not checking patients’ vital signs daily there is the potential for important clinical information to be overlooked. In one of the hospitals surveyed, all patient observations were recorded on the electronic patient record, so this was less of an issue. However, the value of pharmacists speaking to patients should not be ignored. For example, a patient may have questions to ask, information about prescribed or unprescribed medication or adherence issues.

Endorsing drug charts for safety and supply is a key role for pharmacy staff. In some cases, the systems could differentiate stock from non-stock items, and an order electronically generated. However, Foot and Taylor encountered problems with their system not recognising that stock medicines were not sent with the patient when they were transferred to another ward. This could result in patients missing doses of important medicines.2

Electronic transmission of orders may have unexpected consequences. Dispensing may be quicker, especially if a label is generated automatically. However, pharmacists may have to spend more time on the ward when carrying out the clinical screen because, during that process, they ensure that the wording on the label that will be generated once the prescription is confirmed is accurate and unambiguous.

Advantages and disadvantages

Most of the advantages described by respondents were similar to those mentioned in published work in the UK16,25,26 and in the US.11 All interviewees cited legible prescriptions as an advantage. A number of studies have indicated that the quality of handwritten inpatient prescriptions in UK hospitals is poor. One study found that 4–10 per cent of UK hospital prescriptions were illegible or ambiguous and 11–26 per cent had incorrectly written doses.27 Many of the reported disadvantages of EP seem to be associated with the way people work as opposed to the system.

Limitations

Ours was a small survey, because the method only identified hospitals that had published information, or were high-profile EP users. NHS hospitals with a low profile will not have been identified. Bias may also have been introduced by not including hospitals that had tried EP, but had been unsuccessful at implementing it, and by including the views of only one person from each hospital. However, since many of the themes were common across all hospitals, it is unlikely that these limitations have affected the relevance of the findings for other trusts.

Conclusion

In the opinion of the interviewees, EP has had a positive impact on their pharmacies. The system and processes present challenges and opportunities to staff. The way pharmacists carry out their tasks of reviewing medication has required them to adapt to the system and roles may need to be redefined to ensure optimal medicines management. EP can also result in re-evaluation of technician roles to a more patient-oriented focus.

To make the change from a manual system to EP, hospitals should share good practice to develop safe systems. For EP to be successful, a multidisciplinary approach needs to be taken and pharmacists should be part of that structure. It is important to address possible barriers such as training for hospital staff to accept the system and maximise benefit.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Tony Dilks, previously electronic prescribing pharmacist and Gillian Cavell, deputy director of pharmacy, medication safety, King’s College Hospital, for their valuable input. We are also grateful to the hospitals that participated. No sponsorship was required for this study.

About the authors

Reena Mehta, MPharm, MRPharmS, was senior pharmacist, clinical services, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, at the time of the study

Raliat Onatade, MSc, MRPharmS, is deputy director of pharmacy, clinical services, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Correspondence to: Reena Mehta, Senior Pharmacist — Critical Care/Clinical Services, Pharmacy Department, King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS (e-mail: reena.mehta@kch.nhs.uk).

References

- National Health Service Executive information policy unit.Information for health: an information strategy for the modern NHS 1998–2005, a national strategy for local implementation. London: Department of Health, 1998.

- Foot R, Taylor L. Electronic prescribing and patient records — getting the balance right. Pharmaceutical Journal 2005;274:210–12.

- Brennan S, Spours A. Barriers to the successful and timely implementation of electronic prescribing and medicines administration, British Journal of Healthcare Computing and Information Management 2000;17:22–25.

- Brennan S, Spours A. Electronic prescribing and medicines administration: are we overcoming the barriers to success? British Journal of Healthcare Computing and Information Management 2003;20:19–22.

- Miller AS. Computerized prescriber order entry. Pharmacy issues: formulary changes and allergy checking. Hospital Pharmacist 2001;36:1209–12.

- Gouveia W, Shane R, Clark T. Computerized prescriber order entry: Power, not Panacea. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2003;60:1838.

- Wolf EJ. Critical success factors for implementing CPOE. Healthcare Executive 2003;18:14–19.

- Fair M, Pane F. Pharmacist interventions in electronic drug orders entered by prescribers. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2004;61:1286–8.

- Senholzi C, Gottlieb J. Pharmacist interventions after implementation of computerized prescriber order entry. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2003;60:1880–2.

- Grey MD, Felkey BG. Computerized prescriber order-entry systems: evaluation, selection and implementation. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2004;61:190–7.

- Shane R. Computerized physician order entry: challenges and opportunities. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2002;59:286–8.

- Barber N, Cornford T, Klecun E. Qualitative evaluation of an electronic prescribing and administration system. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2007;16:271–8.

- Bhosley M, Sansgiry SS. Computerized physician order entry systems: is the pharmacist’s role justified? Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2004;11:125–6.

- Williams C. Electronic prescribing can increase the efficiency of the discharge process. Hospital Pharmacist 2000;7:206–8.

- Building a safer NHS for patients: improving medication safety. London: Department of Health, 2004.

- Cousins D. Just what are the benefits of hospital electronic prescribing systems? British Journal of Healthcare Computing and Information Management 2001;18: 48–49.

- Tulley M. The impact of information technology on the performance of clinical pharmacy services. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2000;25:243–9.

- Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Laird N, Peterson LA, Teich JM et al., Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA 1998;280:1311–6.

- Audit Commission. A spoonful of sugar. Medicines management in NHS hospitals. London: The Commission, 2001.

- Durieux P. Electronic medical alerts — so simple, so complex. New England Journal of Medicine 2005;352:1034–6.

- Duckworth S. Electronic prescribing reduces errors and saves time through formulary and prescribing control. Pharmacy in Practice 2005;15:233–40.

- Almond M. The effect of the controlled entry of electronic prescribing and medicines administration on the quality of prescribing, safety and success of administration on an acute medical ward. British Journal of Healthcare Computing and Information Management 2002;19:41–6.

- Seger A, Hanson C. Benefits of CPOE. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2004;61:626–7.

- Franklin BD, O’Grady K, Donyai P, Jacklin A, Barber N. The impact of a closed-loop electronic prescribing and automated dispensing system on the ward pharmacist’s time and activities. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2007;15:133–9.

- Ford N, Paul P, Curtis C. The use of electronic prescribing as part of a system to provide medicines management in secondary care. British Journal of Healthcare Computing and Information Management 2000;17:26–9.

- Mitchell D, Usher J, Gray S, Gildersleve E, Robinson A, Madden A et al. Evaluation and audit of a pilot of electronic prescribing and drug administration. Journal of Information Technology in Healthcare 2004;2:19–29.

- Jenkins D, Cairns C, Barber N. The quality of written inpatient prescriptions. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 1993;2:176–9.