Introduction

Large numbers of medicines are taken by haemodialysis patients for a variety of reasons. They are used commonly to treat anaemia and bone disease, for hypertension and diabetes, and to treat or prevent vascular disease. Vitamins are also taken, as are other drugs for renal itch and restless legs. Many dialysis patients have chronic pain which is a further indication for drug therapy. It is important that dialysis patients and care providers know exactly what medicines are being taken in order to assess response to therapy, make appropriate dose adjustments, avoid drug interactions and evaluate possible side effects of treatment. Previous studies have shown that discrepancies between the self-reported use of prescribed medicines and the medical record are common.[1],[2]

Our impression in Dumfries was that the dialysis patients of south west Scotland rarely carried a list of their medicines and could not usually tell us what medicines they were taking. Because of this we designed a renal information booklet, written specifically to help dialysis patients understand why they had been prescribed the medicines they were taking. This booklet contained a list of current medicines and was accompanied by a letter asking the patients to keep the list up to date. We subsequently undertook a medicines reconciliation exercise,[3]

the purpose of which was to determine the number of discrepancies between the medicines list and the medicines dialysis patients were actually taking.

Methods

All 37 haemodialysis patients in Dumfries participated in our survey. We began by posting all patients an information booklet (copies available on request) which included in the sleeve of its inside front cover a list of medicines we believed they were taking, compiled from their most recent clinic letter. This list gave the name of the medicine, the dose, the frequency and the reason it had been prescribed. It was accompanied by a letter asking them to carry their booklet and medicines list with them every time they came for dialysis, also to ensure that the list of medicines was accurate and updated every time their medication was changed. Renal nurses subsequently reinforced the need to carry the booklet and the importance of medicines reconciliation, during dialysis sessions. Four weeks later one of us (FI) interviewed all 37 patients as they were being dialysed in order to establish the number carrying their booklets, the number of booklets that contained a medicines list, and the number of medicines lists that were accurate. This was a structured medicines reconciliation exercise, during which we also consulted Proton (the electronic renal drug record), the renal unit’s drug charts and the emergency care summary, with patients’ permission. (The emergency care summary is a list of medicines prescribed by a patient’s GP. It is a valuable source of information for acute care providers but does not indicate whether the patients is actually taking the medicine and does not include medicines obtained from other sources.) We also asked about over-the-counter preparations and any drugs prescribed by other specialists involved in the patient’s care.

We defined a medicines discrepancy as a difference between the medicine given on the patient’s list and that obtained from the above sources. We categorised discrepancies as doses that were wrong or missing, medicines being taken that were not recorded on the patient’s list, medicines on the list that the patient was not currently taking, and medicines changed for alternatives which had not been recorded on the list. Discrepancies were also categorised by source of prescription (GP or renal unit). We did not count differences in the dose of warfarin or insulin as discrepancies because these changed too frequently, and we did not include the medicines used to lock the patient’s dialysis lines between dialysis sessions. Because the data were not normally distributed, we looked for correlations between age, the number of medicines taken and the number of discrepancies using the Spearman correlation co-efficient.

Results

There were 21 men and 16 women in our cohort, average age 67.3 years (range 18–89 years). Following medicines reconciliation, these 37 patients were found to be taking a total of 459 medicines (mean 12.4, median 12, range 7–20 per patient). GP prescriptions accounted for 324 of these medicines (70.5 per cent) and the renal unit for 118 (26 per cent); 17 medicines were obtained from other sources (three over the counter and 14 from the haematology unit).

Thirty-two patients (86 per cent) were carrying their booklet at the time of the survey. Twenty-nine of these (91 per cent) contained a medicines list but in only one was accurate. Two patients did not have their booklets with them but were carrying a list of medicines separately, although in neither case was this accurate. Thus at least one discrepancy between the list of medicines carried by the patient and the medicines being taking was identified in 36 patients.

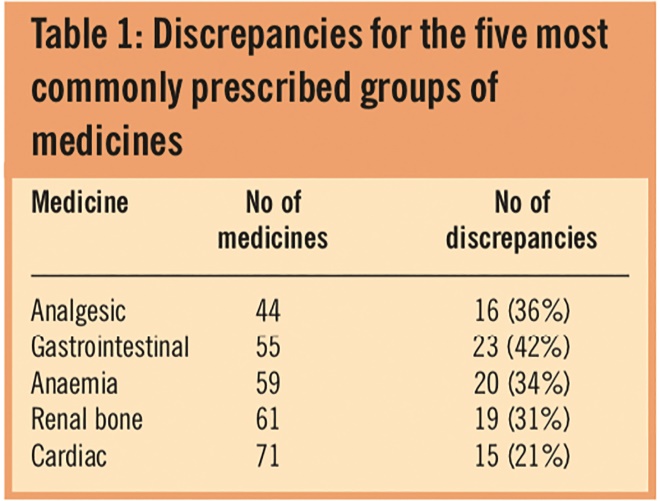

Discrepancies were recorded in 139 (30 per cent) of the 459 medicines that were supposed to be taken. GP-prescribed medicines were at least as likely to be discrepant (106/324; 33 per cent) as renal medicines (30/118; 25 per cent). The commonest error (83/139; 60 per cent) was where patients took a medicine that was not recorded on their medicines list. The next most common error (35/139; 25 per cent) was incorrect dose or dose omitted. The median number of discrepancies per patient was 4 (mean 4.3, range 0–20). Discrepancies for the five most commonly prescribed groups of medicines are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Discrepancies for the five most commonly prescribed groups of medicines

These were not limited to any one class of medicine and ranged from 21 per cent for cardiac medicines (including antihypertensives and statins) to 42 per cent for gastrointestinal medicines (including anti-emetics, medicines to suppress acid secretion, laxatives and antimotility medicines). We suspect that the differences observed may reflect the fact that many patients will not regard laxatives and proton pump inhibitors as important forms of therapy. We looked for correlations between age and number of medicines taken (Spearman correlation co-efficient r=0.22, P=0.24), age and number of discrepancies (r=0.30, P=0.1) and found none. There was, however, a weak correlation between number of medicines taken and number of discrepancies (r=0.44, P=0.01).

Discussion

Only one of our 37 haemodialysis patients was found to be carrying an accurate record of the medicines being taken, despite all patients being provided with a booklet and a letter asking them to do so. We found discrepancies between our patients’ medicine lists and what they were actually taking in 30 per cent of items. Nearly 60 per cent of all discrepancies arose because patients had not recorded the names of medicines they were taking in their medicines lists. Discrepancies were not limited to any one class of medicines and were as likely to occur with medicines prescribed by the renal unit as with medicines prescribed by GPs. We found a weak association between the number of medicines taken and the number of discrepancies, but not between the number of medicines and the patient’s age or the number of discrepancies and the patient’s age. Others have reported similar findings.[4],[5]

Verifying exactly which medicines a patient is taking is a vital if time-consuming task.[6]

Our review of the literature identified seven comparable surveys.[1],[2]

,[7],[8],[9],[10],[11] The design of these studies was slightly different from our own in that they all used information provided by the patient as the gold standard against which the reliability of either physician’s records or the electronic health record were compared. By contrast we used a variety of sources, including the patients themselves and their electronic health records, to establish exactly what each patient was taking and then sought to determine whether the patients had recorded this information on their medicines lists. The main findings in this comparison of surveys were that renal patients take more medicines (average 12 per patient)[1],[2]

than other patient groups (average six per patient),[7],[8],[9],[10],[11]

and that the rate of medicine discrepancies varied from 14 to 60 per cent. The lowest medicines discrepancy rate was reported by the pharmacist-led haemodialysis outpatient clinic.[2]

Why did it prove so difficult to persuade our patients to carry an accurate list of their medicines? When we asked them why they were not carrying their booklets or had not updated their medicines lists, their reasons included simply forgetting, disinterest and the belief that their doctors already had access to this information. We suspect that such responses are linked to lack of compliance and that this in turn reflects complex perceptual barriers that may include doubts regarding the need for so many medicines and concerns about possible side effects.[12]

We did not test these possibilities in our survey.

To our knowledge, only one patient came to harm as a result of carrying an inaccurate medicines list: she knew she was allergic to Maxolon but did not recognise this as metoclopramide and subsequently experienced a facial dyskinesia. The potential for adverse consequences nevertheless exists, as highlighted by National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines.[6] Not being certain what medicines a patient is taking exposes that patient to risks of over- or under-treatment, unwanted side effects, interactions and even the possibility that the wrong medicine might be given, eg, amlodipine instead of amiodarone. The more medicines that are prescribed the greater is likely to be this risk.

How might matters be improved? We took the view that access to the emergency care summary was crucial to the process of verification, while recognising that this did not in itself lead to improved outcomes. We wondered whether our patients’ failure to maintain an accurate medicines list reflected the lack of input from a renal pharmacist in our unit and conducted a small survey of the other nine adult renal units in Scotland to test this possibility. All nine had a designated renal pharmacist but only three were attempting to maintain an accurate electronic medicines list and none of the other units was using its pharmacist to ensure their haemodialysis patients were carrying and maintaining an accurate medicines list. It is counterintuitive, nevertheless, to suggest that a renal pharmacist has no role to play in this challenging area, and we note in our review of comparable surveys that the patient group with the least number of medicine discrepancies was in fact the pharmacist-led hospital haemodialysis outpatient clinic.[2]

We note, moreover, that NICE has recommended pharmacists be involved in the medicines reconciliation process as soon as possible after a hospital admission.[6] Although the NICE guideline was written specifically for hospital inpatients, there is no reason to believe that the process of medicines reconciliation should be any different for renal patients attending an outpatient dialysis facility.

In summary, we have shown that dialysis patients, on average, take a greater number of medicines than other patients. They tend not to keep their medicines lists up to date even when provided with a booklet containing a list of the medicines we thought they were taking and requested to do so. The presence of a renal pharmacist per se does not guarantee greater accuracy, although we note that fewer medicines discrepancies were reported by a renal pharmacist-led outpatient haemodialysis clinic.[2]

Medicines discrepancies pose a significant and ongoing threat to renal patients. We suspect that a simple solution is unlikely but wonder if a combination of a renal information booklet and regular review by a renal pharmacist with access to the emergency care summary may improve outcomes in this challenging and important area of renal care.

Acknowledgement

We thank Josephine Campbell for her help in the preparation of this manuscript.

About the authors

Francesca Irvine, MB ChB, is a foundation year 1 doctor, Alison Almond, MRCP, and Sue Robertson, MB ChB, are associate specialists, Ken Donaldson, FRCP, is consultant physician, Robert Flynn, MSc, GradStat, is statistician and Chris Isles, MD, FRCP, is honorary professor of medicine at Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary renal unit.

Correspondence to: Professor Chris Isles, Renal Unit, Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary, Dumfries DG1 4AP

e-mail chris.isles@nhs.net

References

[1] Lindberg M, Lindberg P, Wikstrom B. Medication discrepancy: a concordant problem between dialysis patients and care givers. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology 2007;41:546–52.

[2] Manley HJ, Drayer DK, McClaran M, Bender W, Muther RS. Drug record discrepancies in an out-patient electronic medical record: frequency, type and potential impact on patient care at a haemodialysis centre. Pharmacotherapy 2003;23:231–9.

[3] Institute for Health Care Improvement. Definition of Medicines Reconciliation. Available at: www.ihi.org (accessed 24 July 2009).

[4] Manley HJ, Bailie GR, Grabe DW. Comparing medication use in two haemodialysis units against national dialysis databases. American Journal of Health System Pharmacy 2000;57:902–6.

[5] Manley HJ, Garvin CG, Drayer DK, Reid GM, Bender WL, Newfield TK et al. Medication prescribing patterns in ambulatory haemodialysis patients: comparisons of USRDS to a large non for profit dialysis provider. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:1842-1848.

[6] National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence with the National Patient Safety Agency. Technical patient safety solutions for medicines reconciliation on admission of adults to hospital. London: NICE/NPSA, 2007.

[7] Wagner MM, Hogan WR. The accuracy of medication data in an out-patient electronic medical record. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 1996;3:234–44.

[8] Bedell SE, Jabbour S, Goldberg R, Glaser H, Gobble S, Young- Xu Y et al. Discrepancies in the use of medicines: their extent and predictors in an out-patient practice. Archives of Internal Medicine 2000;160:2129–34.

[9] Bikowski RM, Ripsin CM, Lorraine VL. Physician-patient congruence regarding medication regimens. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 2001;49:1353–7.

[10] Staroselsky M, Volk LA, Tsurikova R, Newmark L, Lippincott M, Litvak I et al. An effort to improve electronic health record medication list accuracy between visits: patients’ and physicians’ response. International Journal of Medical Imformatics 2008;77:153–60.

[11] Glintborg B, Andersen SE, Dalhoff K. Insufficient communication about medication use and the interface between hospital and primary care. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2007;16:34–9.

[12] Hughes CM. Medication on adherence in the elderly. How big is the problem? Drugs and Ageing 2004;21:793–811.