Abstract

Aim

To analyse the quality of prescribing of low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) for prevention of venous thromboembolism in adult medical patients.

Design

Audit and reaudit

Subjects and setting

50 medical patients were assessed per survey on the medical assessment unit. In total, 100 patients were reviewed.

Results

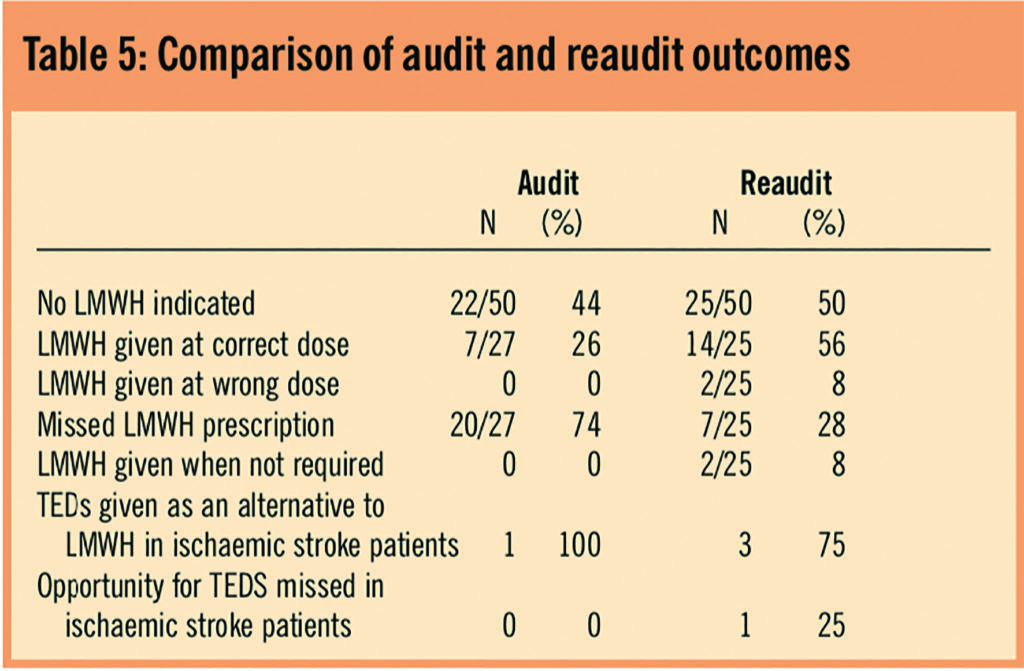

The proportion of cases where LMWHs were prescribed correctly was 26% (7/27) for the initial audit, compared with 56% (14/25) for the reaudit (P=0.027). The number of patients in whom prescribing of LMWHs was missed decreased from 74% (20/27) to 28% (7/25). There was a small increase in the number of incorrect prescriptions in the reaudit.

Conclusions

An educational campaign expressing the importance of using LMWHs in medical patients appears to have increased the rate of prescribing. Further audits with larger patient groups would be required to establish statistical significance.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) accounts for 10 per cent of in-hospital deaths (approximately 25,000 per year) and has a mortality rate which is 10 times that of the more widely publicised meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The annual cost to the NHS of treating VTE (£640m) plus its future complications (a further £400m per year) is considerably greater than preventive practices.1

Hospital admissions for an acute medical illness is independently associated with an approximate eight-fold increased relative risk for VTE.2 Published meta-analyses previously identified the risk of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in medical patients who received no thromboprophylaxis to be approximately 19 per cent.3 Thromboprophylaxis is, indeed, frequently under-prescribed, as the ENDORSE study recently demonstrated.4 Possible reasons for poor implementation include: inadequate education; lack of awareness of this condition by health professionals; that VTE is often a “silent” disease (80 per cent of DVTs are subclinical); and that VTE often occurs after discharge from hospital.5

Two large studies demonstrated a 50 per cent reduction in VTE in acutely ill medical patients by using thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight herparins (LMWHs).6,7 The adverse consequences of VTE vary from death (from massive pulmonary embolism) to minor clinical symptoms. Financial costs arise from initial investigation of symptomatic patients and future treatment, not only in terms of anticoagulation, but subsequent management of side effects that may occur. These may be from adverse effects of the treatment (eg, bleeding, allergy, thrombocytopenia) or secondary to the VTE itself (post-thrombotic syndrome and chronic pulmonary hypertension).

In light of this information, in 2007, the chief medical officer stated thatVTE risk assessment for all new hospital admissions would be mandatory. In particular, patients likely to stay for over four days who have reduced mobility, with severe heart failure, respiratory failure (because of either exacerbation of chronic lung disease or pneumonia), acute infection, inflammatory illness or cancer, should be considered for heparins, both unfractionated and low molecular weight forms (the latter is the preferred prophylactic method).8 This audit was undertaken to assess prescribing compliance.

Method

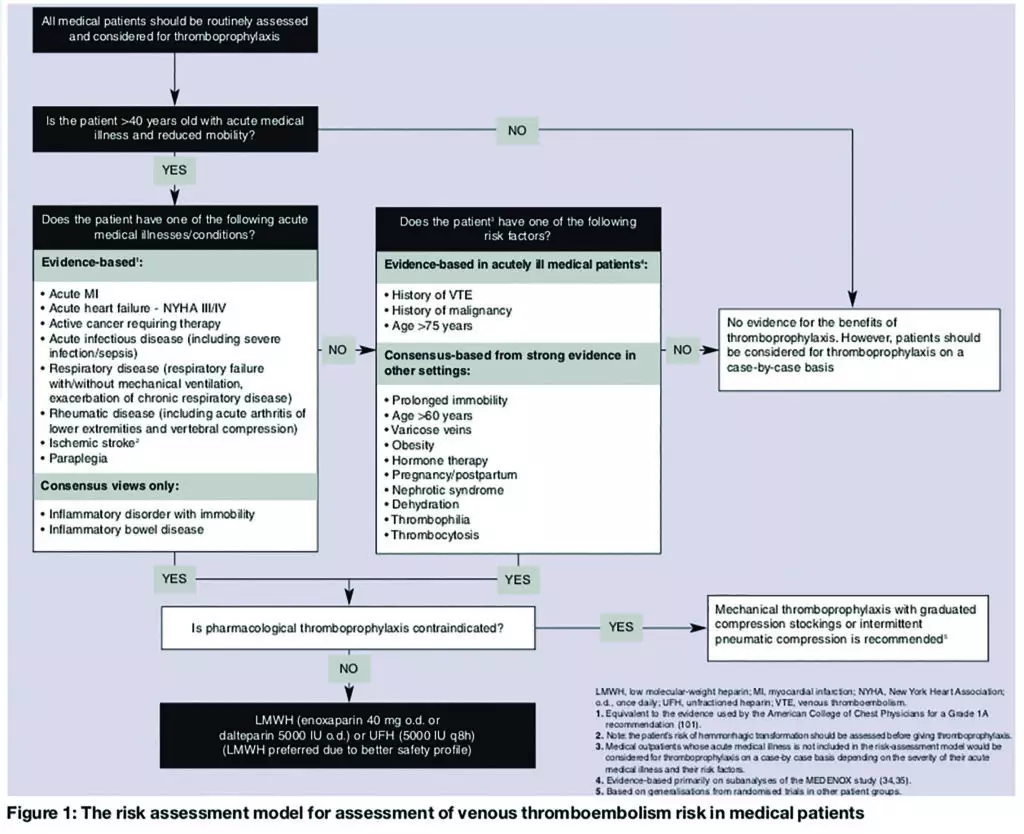

An audit tool was designed using the “risk assessment model for assessment of VTE risk in medical patients” (see Figure 1),9 which includes age, sex and primary diagnosis (of the acute illness). Potential cautions and contraindications (as documented in the British National Formulary) were also taken into account. Thromboprophylaxis prescribed at admission was then documented (LMWH or mechanical methods, such as graduated compression stockings).

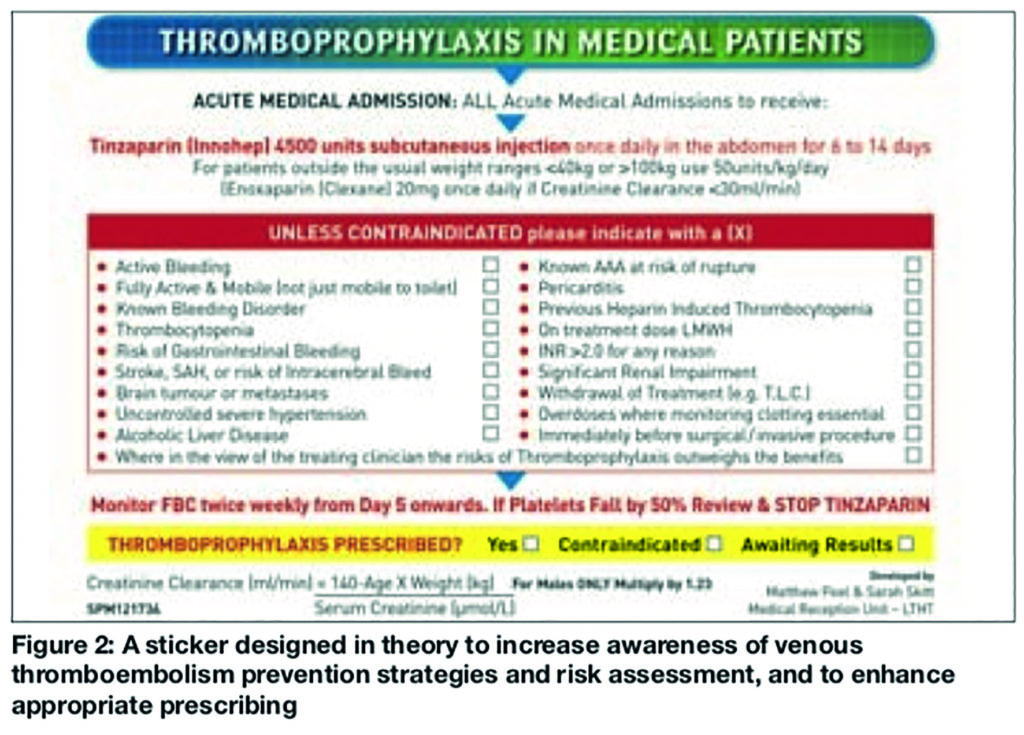

The initial audit of 50 new patients to the medical admissions unit (MAU) was completed over four consecutive days. A sticker, designed to increase awareness of VTE prevention strategies and risk assessment, and to enhance appropriate prescribing, was then inserted into the clerking proforma before patient admission (Figure 2). This enabled a re-audit (of 50 patients) to reassess and compare performance.

Results

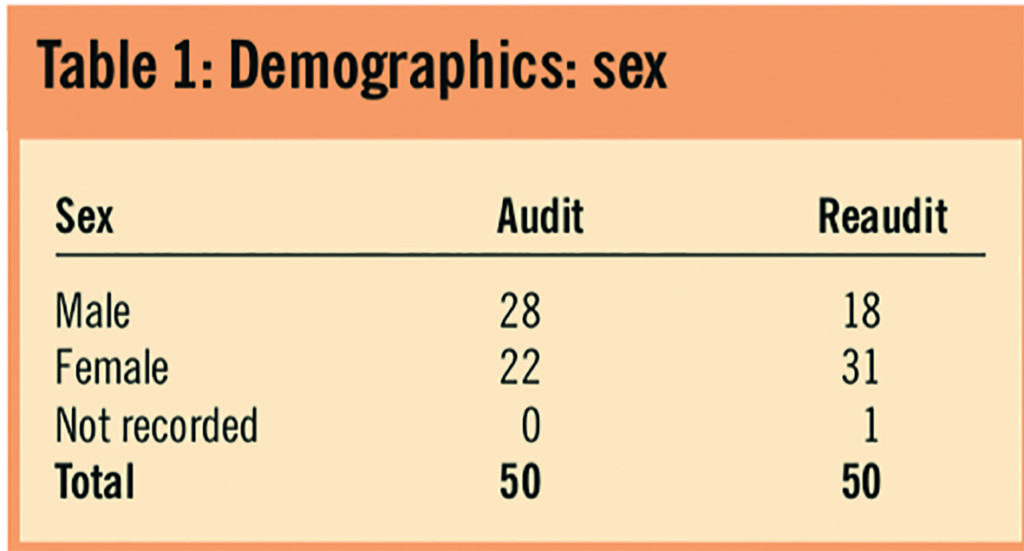

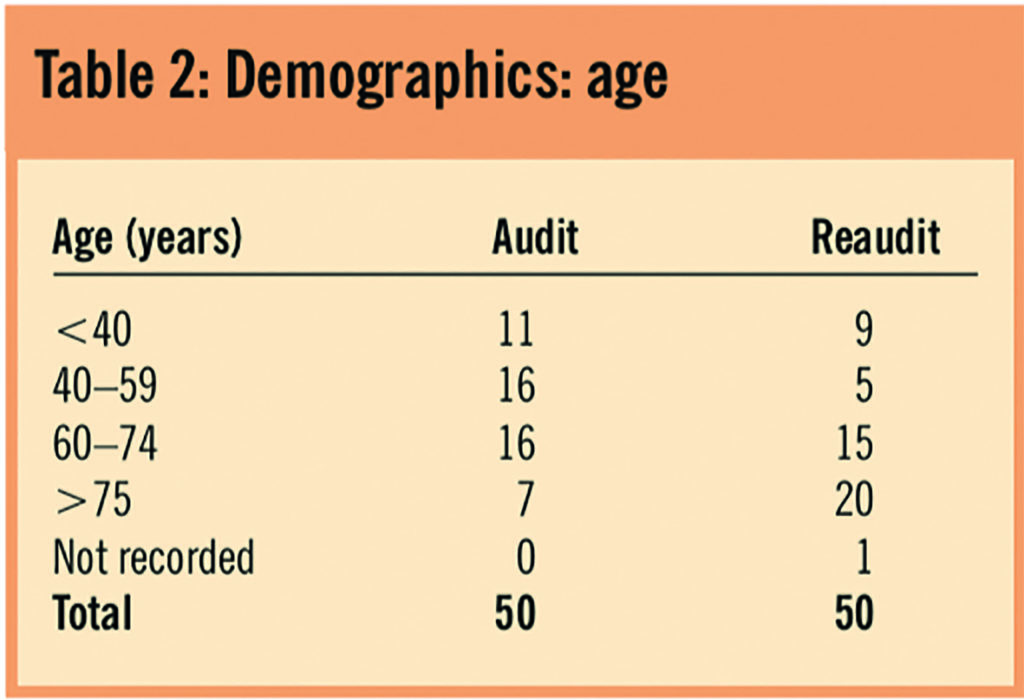

Tables 1 and 2 illustrate the demographics of the audit population.

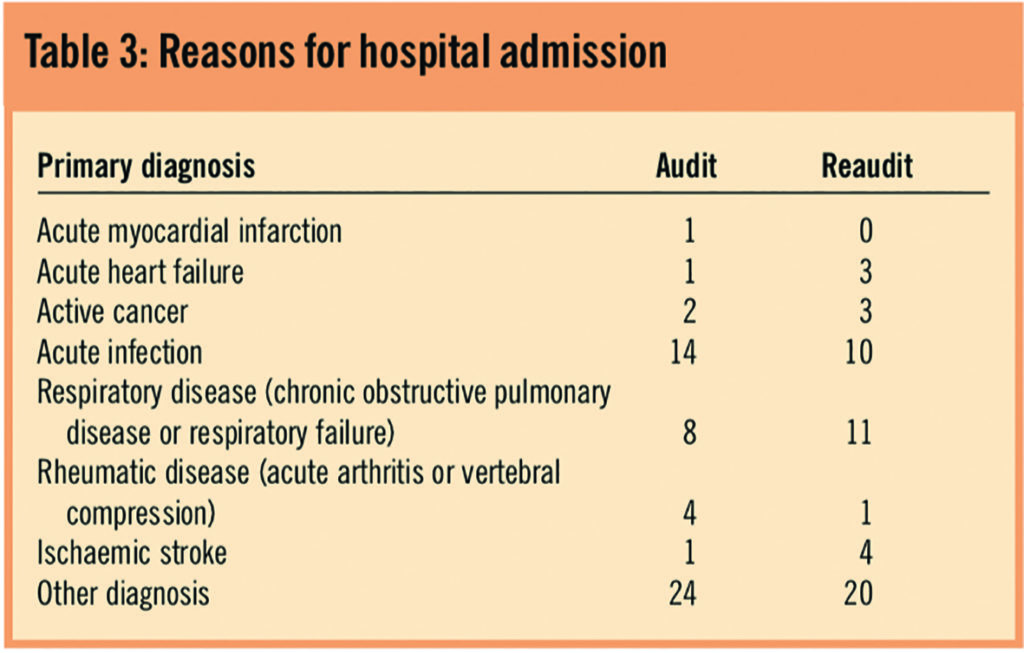

The most common reasons for admission were acute infection and respiratory disease (Table 3).

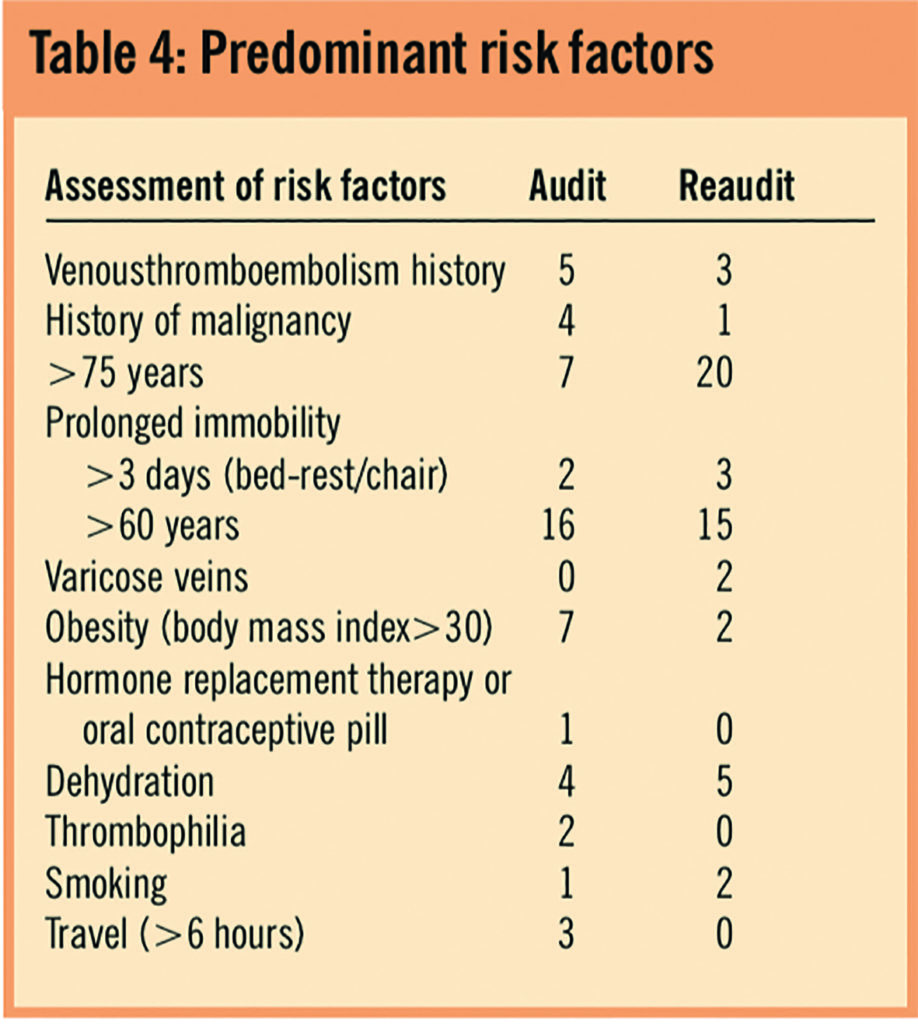

Table 4 demonstrates that the predominant risk factors were being over the age of 60 years, dehydration, obesity and VTE history.

Table 5 shows that there were significantly more patients in the reaudit who received LMWHs at the correct dose than during the initial audit (56 per cent versus 26 per cent, P=0.027). There was also a reduction in the number of patients who did not receive LMWH for whom it should have been prescribed (74 per cent [20/27] in initial audit versus 28 per cent [7/25] in reaudit).

In the reaudit, two patients received LMWHs inappropriately (ie, on warfarin at therapeutic international normalised ratio and fully mobile). In addition, three people prescribed LMWHs had cautions to dosing in the reaudit (renal and elderly), but dose adjustment only occurred in two of these.

Discussion

An improvement in prescribing practice was seen in the reaudit (56 per cent of at-risk medical patients received LMWHs) at a level greater than that of the ENDORSE study (39.5 per cent).5 Despite prominent placement in the admission proforma, the sticker was not completed in most cases. However, it appears to have enhanced awareness. This may reflect prescribers’ lack of knowledge that completion was a requirement.

One issue that had arisen from the audits was lack of guidance regarding the use of graduated compression stockings in combination with LMWHs. Currently, only patients in whom LMWH are contraindicated routinely receive hosiery as an alternative. This is because mechanical methods of prophylaxis have not to date been appropriately evaluated in acutely ill patients, and thus are not recommended at present, except in ischaemic stroke.8,10

However, Irvine and Paterson used a system of classification according to the level of risk of developing VTE.11 Therefore, patients with two or more risk factors (ie, high risk patients) were considered for both thromboprophylactic methods, as supported by evidence from Cochrane Library meta-analyses for surgical patients. Sixteen randomised-controlled trials showed that graduated compression stockings are effective in diminishing DVT risk (number needed to treat=6) and combining another method of DVT prophylaxis with with stockings is more efficacious than stockings alone (NNT=5).12 Hence, during the audit, since there is insufficient evidence to advocate routine prescribing of stockings for every patient, the decision was made to encourage prescribing on the drug chart of compression stockings only in high-risk patients. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines are currently under development regarding VTE prevention and are due for completion in September 2009. It is expected these will include guidance on mechanical methods.

The audit had several limitations, in particular with the sample size. Data were collected on only 50 patients during each study over one week. Analysis showed some encouraging trends, but low numbers meant the audit was not powered to the 80 per cent level needed to demonstrate significant improvement in prescribing. For future audits to reach this required level, the minimum number of patients recruited should be 100 per data set (ie, those suitable for LMWHs). Only half the data set in the current audit had analysable results.

Secondly, the period for information collection could also be increased to take into account seasonal changes in the patient population, such as the increased number of patients with respiratory illnesses in the winter months.

Thirdly, it was not feasible to examine outcomes during admission from the changes to the service because of the high turnover of patients on the ward.

Actions for the future include incorporating the thromboprophylaxis sticker into preprinted versions of the medical admissions clerking booklet. It may be plausible to audit the degree to which this information booklet is completed, with a view to establishing a connection between this process and improved prescribing. Alternative prescribing devices could be used (eg, preprinted line on the drug chart “low molecular weight heparin for thromboprophylaxis”). Furthermore, establishing a rolling audit that examines thromboprophylaxis would not only benefit MAU staff with clinical data for their portfolios, but would also lead to improved monitoring of LMWH and compression stockings prescribing. This could occur quarterly to coincide with junior doctor rotations. Future audits should involve greater patient numbers over a longer time period to provide data that show more consistent trends. All results should be presented to the multidisciplinary team working in acute care. Additionally, medical student training could incorporate information on thromboprophylaxis and enhance awareness.

Finally, future audits should include an element of patient involvement. The practice and quality improvement directorate of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society summarises the components of good quality clinical audit, one of which is a clear patient focus.13 The guide states it is through patient experiences that clinical quality and clinical outcomes become more meaningful. In the context of the audit, this refers to patients’ experience of wearing compression stockings, and understanding the role of a potentially painful subcutaneous injection daily during their hospital stay. A patient questionnaire should hence be included in future studies. Additional patient involvement is to encourage mobilisation where appropriate, a measure that was recommended in the NICE guidance for thromboprophylaxis in surgical patients.

In conclusion, the use of a prescription aid appears to improve LMWH use on the MAU in patients at high risk of VTE. However, there is considerable room for improvement and it is vital that awareness is raised to reduce the financial and physical burden of the consequences of VTE.

Acknowledgements

Charlie Walker, Sarah Skitt and Matthew Peel, resident pharmacists at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

About the authors

Sarah L. Hoye, MBChB, MRCP, is specialty registrar in acute medicine, medical assessment unit, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds

Stuart E. Bond, MRPharmS, Dip Pharm Prac, is specialist pharmacist, medical assessment unit, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds

Correspondence to: Sarah L. Hoye, 18 Coldwells Hill, Stainland, Halifax, West Yorkshire HX4 9PG (tel 07790 437648; e-mail sarahhoye@hotmail.com)

References

- The House of Commons Health Select Committee. The prevention of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. London: House of Commons; 2005.

- Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Pettersen TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ 3rd. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Archives of Internal Medicine 2000;160:809–15.

- Report of expert working group on prevention of VTE. Available at www.dh.gov.uk (accessed 28 July 2009)

- Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann J-F, Goldhaber SZ, Kakkar AK, Deslandes B et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. The Lancet 2008;371:387–94.

- Fitzmaurice DA, Murray,E. Thromboprophylaxis for adults in hospital. An intervention that would save many lives is still not being implemented. BMJ 2007;334:1017–8.

- Samama MM, Cohen AT, Darmon JY, Desjardins L, Eldor A, Janbon C et al. Comparison of enoxaparin with placebo for prevention of VTE in acutely ill medical patients (MEDENOX). New England Journal of Medicine 1999;34:793–800.

- Leizorovicz AT, Cohen AG, Turpie G, Olsson C-G, Vaitkus PT, Goldhaber S Z et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of dalteparin for prevention of VTE in acutely ill medical patients (PREVENT). Circulation 2004;110:13–9.

- Report by Chief Medical Officer 2007. Available at www.dh.gov.uk (accessed 28 July 2009).

- Cohen AT, Alikhan R, Arcelus JI, Bergmann JF, Haas S, Merli GJ et al. Assessment of venous thromboembolism risk and the benefits of thromboprophylaxis in medical patients. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2005;94:750–9.

- Lippi G, Guidi GC. Thromboprophylaxis in stroke patients (letter). Stroke 2005;36:2067.

- Irvine NJ, Paterson J. Improving local practice of venous thromboembolism prevention in medical patients. Acute Medicine 2007;6:79–81.

- Cochrane Library. Elastic compression stockings for prevention of deep vein thrombosis 2000;4.

- Practice and quality improvement directorate. Guide to audit. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2005;275:203–4.