This content was published in 2006. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

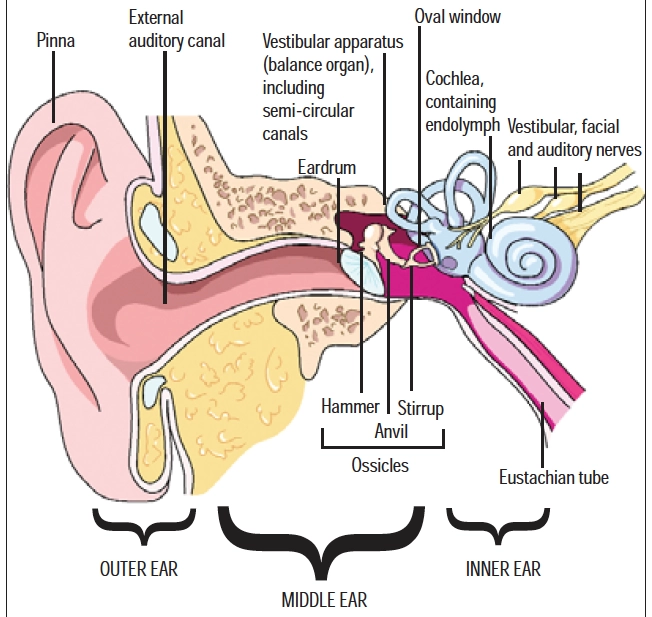

The ear consists of three parts: the outer ear, comprising the pinna (auricle) and external ear canal that leads inwards to the eardrum; the middle ear cavity that connects with the throat via the Eustachian tube; and the inner ear, comprising the cochlea, with its sound receptors, and the vestibular apparatus, which is associated with balance.

The external ear

The conspicuous funnel-like flap of the pinna is made of cartilage. Its function is to direct sound waves into the external ear canal and towards the eardrum. The ear canal is about 2.5cm long in adults and the outer third contains glands that secrete cerumen and sebum. Cerumen is a wax-like substance. Its purpose is to trap dust and foreign particles and to repel water, thus keeping the ears clean. Cerumen also has some bactericidal and fungicidal activity. The appearance of cerumen is genetically determined. Asians are more likely to have a dry type (grey and flaky), whereas Caucasians and Africans are more likely to have a wet type (honey to dark brown and moist).

Excessive or impacted earwax

Earwax is a combination of cerumen, sebum, dead cells, sweat, hair and dust. Aided by jaw movement, it slowly migrates to the ear opening where it falls out.

Wax in the ears causes much unnecessary concern — in most circumstances, it is not necessary to clean the ear canals. However, sometimes earwax can build up, particularly in people with a lot of hair growing in their ears, in those with narrow ear canals and in users of hearing aids or ear plugs. This wax can impede the passage of sound (causing conductive hearing impairment) and give a feeling of fullness, itching and sometimes tinnitus and dull pain.

Using cotton buds to clean the ear canals is not recommended. It risks both damage to the sensitive lining of the ear canal (and infection) and the ear drum, and usually serves only to push the wax further in. Jaw movement helps the ear’s natural cleaning process so chewing gum or talking may help those predisposed to wax build-up.

Impacted earwax can be problematic and is more common in older people — just under a third experience impacted ear wax. With age, the glands secrete less sebum and cause the wax to be drier and harder, increasing the likelihood of impaction. Wearing hearing aids can compound the problem.

Pharmacists can recommend cerumenolytics (ear wax softeners) to aid removal of impacted wax. There are many products on the market, containing a variety of ingredients including urea-hydrogen peroxide, docusate sodium, sodium bicarbonate, glycerine and arachis, olive or almond oil. These ingredients work in different ways to soften the wax (eg, oils, docusate sodium), to increase water penetration of the wax (eg, urea, glycerine) or to aid wax removal mechanically (eg, peroxide preparations release bubbles of gas to unclog the wax or break it up).

Identify knowledge gaps

- Do you remember the anatomy of the ear?

- What is the usual treatment for otitis externa?

- What factors increase the risk of “glue ear”?

Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s areas of competence for pharmacists are listed in “Plan and record”, (available at: www.rpsgb.org/education). This article relates to “common disease states”.

There is no clear evidence of the effectiveness of any one agent over another. Prodigy recommends the use of tap water, sodium chloride 0.9 per cent or sodium bicarbonate ear drops. Olive oil is also recommended. Care must be taken with respect to nut allergy if recommending preparations containing arachis or almond oil. Preparations containing organic solvents can irritate and inflame the ear. Panel 1 describes how to instil ear drops.

Panel 1: How to instil ear drops

- Ear drop instillation is most comfortable if the ear drops are first warmed by holding in hands or placing in container of warm (not hot) water

- Lie down with affected ear uppermost

- Gently pull the pinna back and up (just back in children), to open the ear canal

- Place the required number of drops into the ear

- Remain in position for about five minutes allowing drop(s) to drain into the ear canal

Cerumenolytics may take up to a week to achieve the desired effect. If there is still no symptom relief, syringing by the GP or nurse may be required. A stream of water at body temperature is passed into the ear at a rate of 10ml per second (for adults), and the wash and ear wax is collected beneath the ear. Contraindications to syringing include a history of perforated eardrum, unilateral deafness and a history of recurrent otitis externa. The use of softening ear drops 30 minutes before syringing facilitates removal. In resistant cases ear drops may be used for three to five days before syringing.

Dermatitis

Dry skin and itching or irritation of the pinna or ear canal can be caused by dermatitis and can be treated with an emollient, such as aqueous cream.If the ear canal is affected then a liquid, such as olive oil, may be used.

Contact dermatitis caused by sensitivity to earrings is common. Affected patients can be advised to wear nickel-free earrings or use a proprietary lacquer to coat earrings. In the absence of any signs of infection, topical hydrocortisone is usually an effective treatment. Other causes of contact dermatitis include use of earplugs or hearing aids. Seborrhoeic dermatitis can affect the ears in isolation or occur alongside scalp dandruff or eyebrow scaling. It is an eczematous reaction provoked by commensal yeasts. This can be managed with steroid drops and creams.

Otitis externa

“Otitis externa” (or “swimmer’s ear”) refers to inflammatory conditions of the pinna or external ear canal, including the outer surface of the eardrum. Predisposing external factors include ear trauma, use of cotton buds, syringing, excessive moisture (eg, caused by frequent swimming), humid environments, dermatitis or eczema and chemicals (eg, shampoo, hair dyes). There may be localised (furuncle) or diffuse associated bacterial infection (commonly Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus). Less commonly a fungal infection (Candida albicans) can follow prolonged topical corticosteroid or antibiotic use.

A furuncle is an infected hair follicle in the outer ear canal, usually caused by S aureus. The patient will experience severe pain, particularly when the pinna is moved, and a small red swelling can often be seen. Applying a hot flannel to the affected ear and taking oral analgesics are often sufficient management but, if symptoms are severe oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin) may be needed.

Acute otitis externa affects 10 per cent of people at some point in their lives. Symptoms include ear pain, itching, impaired hearing and discharge (foul smelling). The ear appears red, swollen or scaly. Treatment of inflammation is usually with topical corticosteroids, or, in the case of infection, with an anti-infective ear drop preparation, with or without a corticosteroid. Corticosteroids should not be used where inflammation is caused by infection. Acetic acid 2 per cent ear drops are available over the counter and on prescription and can be used first-line to treat bacterial or fungal disease, or both. They are less likely to cause superinfection than corticosteroids but, because they are acidic, they can sting. Alternative topical antibacterial ear drop preparations include aminoglycosides but these are usually contraindicated when there is a risk of eardrum perforation because of their risk of ototoxicity. Chloramphenicol is sometimes used, although propylene glycol in the eardrops causes sensitivity in about 10 per cent of patients.

Clioquinol has antibacterial and antifungal activity and is, therefore, useful when the cause of the infection is uncertain. In all cases, treatment with topical antibacterial or corticosteroid should not exceed seven days to avoid secondary fungal infection or sensitisation. Fungal infections are difficult to treat and require specialist attention. It is important to clear the ear canal of debris and discharge before starting treatment and gentle syringing may be needed. The patient should be advised to avoid scratching and cleaning the ear with cotton buds and to keep the ear dry. Over-the-counter pain relief should be sufficient.

Acute otitis externa may become chronic if trauma, inflammation or infection continues long term.

The middle ear

The external ear is separated from the middle ear by the eardrum — the tympanic membrane that vibrates in response to sound waves. This thin membrane is normally continuous but can be perforated as a result of trauma or infection. The vibrations of the eardrum transmit sound to the middle ear cavity.

The middle ear is an air-filled cavity, about 1.3cm wide, connected to the nose and throat via the Eustachian tube. The primary function of the Eustachian tube is to keep pressure inside the ear at ambient air pressure. A second function is to allow drainage of any accumulated secretions, including those caused by infection, or debris.

Three tiny bones, the malleus (hammer), the incus (anvil) and the stapes (stirrup), collectively called the ossicles, stretch across the middle ear cavity. Their function is to conduct vibrations from the ear drum to the oval window, one of two membrane covered openings to the inner ear.

Blocked Eustachian tube

Eustachian tube problems and associated ear infections are among the most common problems seen in primary care. Normally closed, the Eustachian tube prevents contamination of the middle ear, but it opens when a person swallows, blows his or her nose or yawns.

Upper respiratory tract infections and allergies commonly cause swelling and increased mucus production in the ear, nose, throat and the Eustachian tube. As a result, the Eustachian tube can become compromised or blocked. This causes air pressure to fall within the middle ear. As a consequence, the ears feel full and hearing is muffled. If pressure continues to fall, a vacuum can result, drawing fluid into the middle ear cavity. Fluid accumulation in the middle ear is a common, painless occurrence in early childhood and can result in inflammation of the middle ear or “glue ear” (see below). If the Eustachian tube remains occluded, the individual may be predisposed to a middle ear infection. The use of nasal and oral decongestants can reduce secretions and swelling, allowing the Eustachian tube to open and air pressure to equalise.

Ear pain during flights

Pressure imbalances can also occur in rapidly descending or ascending aeroplanes. If the Eustachian tube is narrow or occluded, ear pressure may be prevented from being normalised to that of the outside. The problem is worse during aircraft descent because air is usually capable of being forced out via the Eustachian tube as outside pressure drops (ascent), but it is less likely to get through when the pressure outside is increasing (descent). People with an upper respiratory tract infection or sinus problems and babies and young children, who have small Eustachian tubes, are more susceptible to this ear pain during flight descent.

Decongestant use before flying can also reduce ear pain in susceptible individuals. A decongestant spray, such as xylometazoline, may be helpful if used one hour before ascent and again before descent if the flight is a long one. Alternatively, a decongestant tablet (eg, pseudoephedrine) can be taken. For children older than three months, one drop into each nostril of ephedrine nose drops, again one hour before ascent or descent may be helpful.

Disposable earplugs, such as EarPlanes, are marketed to prevent the ear pain experienced by travellers in aeroplanes. Inserted before ascent and descent, these ear plugs have a filter system aimed at regulating air flow to and from the ears. Other ways of reducing ear pain during flights are listed in Panel 2.

Panel 2: Tips for avoiding ear pain during flights

- Young children can suck sweets or chew gum during descent to encourage Eustachian tube function

- Infants can be given a feed on commencing descent

- The ear can be “cleared” by swallowing or yawning, or by performing manoeuvres, such as pinching the nose then swallowing or blowing out through a pinched nose

Otitis media

Acute otitis media often follows an upper respiratory tract infection. The infecting virus or bacterium (Streptococcus pneumoniae in 40 per cent of cases and Haemophilus influenzae in 25 per cent of cases) passes from the throat to the middle ear via the Eustachian tube. Such an infection can affect one or both ears. Most (75 per cent) cases of acute otitis media occur in children under 10 years of age. One in four children has an episode of acute otitis media before the age of 10 years, with a peak incidence between three and six years of age.

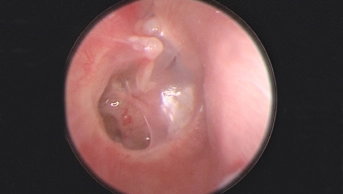

Pain is the predominant symptom of otitis media. It may present as ear pulling, sleeplessness and irritability in children who are unable to communicate their symptoms verbally. Fever is also common. Using an otoscope, the GP will see a bulging and inflamed red or yellow ear drum or a perforated eardrum with discharge of pus. Perforation of the eardrum often gives relief of symptoms and usually heals naturally with no detriment to hearing. Most cases (80 per cent) of acute otitis media resolve within three days with no treatment. Recurrent episodes are more common in white males, people with asthma, a history of tonsillitis or enlarged adenoids, and in children who are bottle fed, use a dummy or who attend day care.

There is no consensus on the best way to treat acute otitis media and there is wide variation between doctors in different countries. For example, only 31 per cent of acute otitis media cases in the Netherlands are treated with antibiotics compared with 98 per cent of cases in Australia and the US. Antibiotic use does not appear to decrease the incidence of long-term complications resulting from recurrent infection. Where antibiotic treatment is given, amoxicillin, with or without clavulanic acid, is the drug of choice. The duration of antibiotic treatment is usually five days in the UK, although once again this varies across the globe. Azithromycin is an alternative if amoxicillin is contraindicated, because it is active against all common organisms involved in acute otitis media. In contrast, erythromycin has poor activity against H influenzae. The associated pain and fever of acute otitis media can usually be managed effectively with paracetamol or ibuprofen. According to Prodigy, homoeopathy is unlikely to be of any benefit.

Glue ear

Otitis media with effusion (glue ear) is chronic inflammation of the middle ear accompanied by accumulation of fluid. It generally causes no discomfort and the usual presenting symptom is impaired hearing. However, the temporary deafness caused by otitis media with effusion can affect a child’s educational, social and language development. Children are particularly vulnerable to glue ear because their Eustachian tubes are shorter and lie horizontally, making blockage more likely. One study found 80 per cent of children to have otitis media with effusion at least once before the age of four years. Risk factors include:

- Being male

- Exposure to tobacco smoke

- Young age (peaks at two years)

- Formula feeding

- Season (more prevalent in winter)

- Sibling history of glue ear

- Attendance at nursery or day care

On examining the ear, the GP may see changes to the ear drum, including opacity, yellow or amber colouration, decreased mobility and concave appearance. Usually a child with hearing loss is referred to specialist audiology clinics.

Treatment of glue ear is generally not indicated since 50 per cent of cases resolve naturally within three months and 95 per cent within a year. Persistent cases may require surgery. For example, a tiny ventilation tube (a grommet) can be put into the eardrum under general anaesthesia. Grommets improve hearing immediately and usually stay in place for six months to a year, when they fall out naturally. Antibiotics, corticosteroids, antihistamines and decongestants are not recommended for glue ear.

In older children, the technique of autoinflation is occasionally used. The child uses a device (Otovent — not available on the NHS) to blow up a balloon using their nose, so forcing open the Eustachian tube. This allows normalisation of air pressure. Used three times a day over several weeks it can improve hearing, although there is little good quality evidence of its efficacy.1

A second article, looking at conditions affecting the inner ear (eg, Meniere’s disease), ototoxic drugs, hearing impairment and hearing aids will be published on 4 February.

References

1. Williamson I. Otitis media with effusion: autoinflation. Clinical evidence. Available at: www.clinicalevidence.com (accessed 12 January 2006).

Resources

- Bredenkamp JK. Earwax. Available at: www.medicinenet.com (accessed 12 January 2006).

- Eustachian tube problems. www.medicinenet.com

- Prodigy guidance for otitis externa, otitis media (acute) and glue ear. Available at: www.prodigy.nhs.uk (accessed 12 January 2006).

Action: practice points

Reading is only one way to undertake CPD and the Society will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio.

- Next time you advise parents of children with glue ear, ask about smoking.

- Counsel patients buying products to remove ear wax on their correct use.

- Discuss ear pain with families buying products for travel.

Evaluate

For your work to be presented as CPD, you need to evaluate your reading and any other activities. Answer the following questions: What have you learnt? How has it added value to your practice? (Have you applied this learning or had any feedback?) What will you do now and how will this be achieved?