Shutterstock.com/Science Photo Library/Grook Da Oger(Wikimedia Commons)

By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Identify common childhood rashes and understand their typical presentations;

- Differentiate between rashes that are self-limiting and those requiring medical intervention;

- Recognise accompanying symptoms that may indicate serious underlying conditions necessitating urgent referral;

- Provide appropriate advice on the management and treatment of various rashes in children.

Childhood rashes are common — most are harmless, have no cause for concern and disappear without treatment. If a child is in good health and has no other symptoms, simple observation of the rash over the following few days may be sufficient and the rash should disappear without needing significant treatment. If the rash is accompanied by high fever, breathing difficulties, vomiting or reduced general health, it may indicate something more serious.

Patients aged under 15 years comprise around 20% of the average GP list and account for one in four GP consultations. Schoolchildren visit the GP between two and three times per year, but this figure is doubled in children aged under five years who visit the GP on average six times per year1.

Skin rashes in children require careful history taking, assessment and skin examination. This article describes a range of rashes in paediatric patients, according to a step-by-step approach to the classification and identification of the rash.

Rash with fever

Slapped cheek syndrome

Slapped cheek syndrome (also called fifth disease or erythema infectiosum) is caused by parvovirus B19. This infection is most common in children, although it can occur in people of any age2. Infection is also seasonal, with increases observed in spring and early summer, and additional increases in incidence occurring every three to four years3. While there had been low activity since 2018, reported cases of parvovirus B19 began to increase at the end of 2023 and beginning of 2024. Activity has now surpassed the levels seen in the most recent previous peak years in 2017 and 20183.

Patients usually develop symptoms 4–14 days post-infection, but sometimes these may not appear for up to 21 days. The defining feature is a bright red rash on one or both cheeks, often with an accompanying paleness around the mouth4. Other symptoms can also include low-grade fever, runny nose, sore throat, headache, upset stomach and generally feeling unwell2.

Figure 1 shows slapped cheek syndrome rash in different skin tones5.

A light pink erythematous, macular rash may also appear on the chest, stomach, arms and thighs4. This often has a raised, lace-like appearance and may be itchy, clearing spontaneously within a few days. The rash may be less obvious on brown and black skin and might look brown, grey or purple on dark skin2,6.

Children should be encouraged to rest and drink plenty of fluids, and babies should continue their normal feeds2. If the child is experiencing fever, headache or joint pain, they can be treated with paracetamol and ibuprofen. Additionally, antihistamines can be used to help with any itching. Once the rash has formed, the child is no longer contagious; therefore, it is not necessary for him or her to stay away from school or nursery, or to avoid contact with pregnant women. However, parents and carers should inform anyone who has been in contact with the child during the prodromal period so they can be managed effectively4.

Chickenpox

Chickenpox is caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV). The infection commonly occurs in childhood, but may occur at any time7. Chickenpox is usually a self-limiting disease in healthy children.

The symptoms of chickenpox begin one to three weeks after infection. The main symptom is a rash that develops in three stages:

- Spots — small, red erythematous macules develop on the face or chest before spreading to other parts of the body. In darker skin tones, chickenpox spots may start as violet, brown, or skin-coloured spots8;

- Blisters — over the next few hours or the following day, very itchy fluid-filled blisters develop on top of the spots and have a typical erythematous halo;

- Scabs and crusts — after a further few days, the blisters dry out and scab over to form a crust; the crusts then gradually fall off by themselves over the next week or two9.

Chickenpox is contagious until all the blisters have scabbed over, which usually occurs around five or six days after the rash first appears9.

Mild cases of chickenpox only require symptomatic treatment. Relief of itching and prevention of scratching, which predisposes to secondary bacterial infection, may be difficult, especially in younger children10. Antihistamines can help with itching, as well as wet compresses, sodium bicarbonate baths and colloidal oatmeal baths10. For neonates (children aged less than 28 days), specialist advice for management should be sought immediately9. More information on the recognition and management of chicken pox can be found in ‘Chickenpox: symptoms, treatment and potential complications’

When chickenpox heals, black people and those with darker skin tones are more likely to develop discoloured spots that can take longer to heal8.

Hand, foot and mouth

Hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) results from enteroviral infection, most commonly Coxsackie A16, although other group A and B Coxsackie viruses may be causative. Less commonly, but more seriously, it can be caused by enterovirus 7111.

The first observed symptom is usually a low-grade fever, followed by scattered papules that develop into vesicles affecting the hands, feet and mouth, where they progress to shallow ulcers11. The spots can be harder to see on darker skin tones, so it is advised to check the palms of hands and the bottom of feet where the condition may be more noticeable. Lesions may also be present on other parts of the body (e.g. buttocks and groin)12.

The condition is typically mild and self-limiting, resolving within ten days. Children should be encouraged to drink plenty of fluids. Paracetamol or ibuprofen can be used for fever and pain, using the doses given in the BNF for Children11,13. A topical analgesic or anaesthetic, such as benzydamine hydrochloride or lidocaine, may be recommended.

Patients should be referred to A&E if they have any of the following symptoms:

- Any signs of dehydration (e.g. passing little or no urine);

- Developing seizures, confusion or weakness;

- A temperature of 38°C or above (for children aged under three months) or a temperature of 39°C or above (for children aged between three months and six months);

- If there is any discharge of pus;

- If symptoms are getting worse or have not improved after seven to ten days11.

Scarlet fever

Scarlet fever is an infectious disease caused by toxin-producing strains of the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as group A streptococcus (GAS). Any child presenting with symptoms of scarlet fever needs to be referred to their GP immediately.

The identification of the M1UK strain of Streptococcus pyogenes has been linked with a rise in scarlet fever and invasive group A streptococcal infections in the UK14. This strain exhibits enhanced transmission capabilities, contributing to the increased incidence. Additionally, reduced exposure to common pathogens during the COVID-19 pandemic may have led to decreased immunity in the population, particularly among children14. Additional information on group A streptococcus can be found in ‘Everything you need to know about group A streptococcus infections’.

Onset is usually rapid, with fever, sore throat, vomiting, headache, abdominal pain, myalgia and malaise15. This is followed 12–48 hours later by a blanching rash, which usually starts on the neck then extends to the trunk and extremities. The tongue may also be covered in a heavy white coating, through which red papillae may be visible. The white covering disappears after a while, leaving the tongue with a beefy red appearance (known as ‘strawberry tongue’)15.

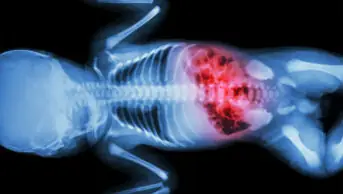

Source: Science Photo Library

The rash is a fine erythematous punctate eruption, which blanches with pressure. This is followed by dry rough skin, with the feel of sandpaper. Seven to ten days later, desquamation of all affected areas will occur, which may last on the palms for up to a month15.

Scarlet fever is highly contagious and, if not treated with antimicrobials, can be infectious for two to three weeks after the onset of symptoms (with antimicrobials it remains infectious for 24 hours after starting treatment). Scarlet fever is treated with antibiotics and symptomatic relief (e.g. paracetamol to reduce the fever), and fluids should be maintained to prevent dehydration15.

Rash with itching

Prickly heat rash/heat rash

Heat rash is an uncomfortable but usually harmless condition. Prickly heat (also known as miliaria rubra) appears without a preceding disorder and should clear up after a few days without treatment16.

Heat rash appears as small red spots on white skin, while on brown or black skin it may be harder to see or appear grey or white. The rash consists of numerous papules around the size of a small pin head, which are elevated so as to produce a considerable roughness of the skin, itchy and prickly feeling with mild swelling and redness. They can appear anywhere on the body16.

Treatment includes avoiding excessive heat and humidity, ensuring adequate fluid intake, wearing loose cotton clothing and using calamine lotion. On GP advice, a mild steroid cream, such as hydrocortisone cream, may be prescribed16.

Eczema

Atopic eczema (also known as atopic dermatitis) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that causes the skin to become itchy, dry and cracked17. The affected skin can become red, white, purple or grey, or lighter or darker than the skin around it (depending on skin tone)17.

Although atopic eczema can affect any part of the body, it mainly affects the hands, insides of the elbows, backs of the knees and the face and scalp. In some children, the condition will improve, or even clear completely, as they age17.

Patients should be advised to avoid drying agents (e.g. soap, prolonged bathing and chlorinated pool water). Bath oil and fragrance-free emollients can help, and oral antihistamines can be considered for severe itching (oral antihistamines should not be used routinely in the management of atopic eczema in children). Patients can also be prescribed topical steroids to reduce swelling, redness and itching during flare-ups18.

Pharmacists and healthcare professionals should consider the severity of atopic eczema, the child’s quality of life (e.g. everyday activities and sleep) and psychosocial wellbeing when deciding on management options18. Patients should be referred to their GP if their skin is cracked or blistered, if there is a history of atopic eczema in the family, if the child has allergies and/or asthma, or if the patient has painful eczema or fever18.

Hives

Hives (also known as urticaria) is a superficial swelling of the skin. Hives can occur owing to certain allergies to foods, drugs, insect bites, skin contact to chemicals, or cold or heat exposure19.

Hives are small, raised areas (1–2cm) of the skin that develop suddenly and are surrounded by redness. On white skin, they often look red or white, while on brown and black skin, they can be harder to see. The rash may disappear but may reappear in hours or days. Hives may coalesce with others, making the rash look extensive20. The rash is often itchy and can be localised or generalised20.

As hives tends to be self-limiting, treatment is often not required; however, patients should avoid trigger factors and should use calamine lotion and/or oral antihistamines for treatment. Topical corticosteroids can also be used for severe cases19. Referral to a GP may be required if symptoms persist for more than six weeks and are associated with pain and fever.

Ringworm

Ringworm (also known as tinea) is a common fungal infection of the skin, caused by dermatophytes, that can appear almost anywhere on the body. It is not serious and can usually be treated easily, however, it is contagious (e.g. through direct contact with an infected person or animal)21.

Ringworm appears as single or multiple circular red or silvery ring-like rashes on the skin21. The colour of the ringworm rash may be less noticeable on brown and black skin21. Blisters and pus-filled sores may form around the rings. The skin can be inflamed and itchy.

For mild, non-extensive ringworm, topical antifungal creams, such as clotrimazole cream 1%, can be used for treatment22,23; however, more serious infections may need to be referred to a GP, where either stronger topical preparations or oral antifungals may be required. Babies aged less than one month should always be referred to their GP. If the patient has symptoms on the scalp, ringworm that has not improved after two weeks of over-the-counter antifungal cream, or if the patient has an underlying condition, is immunosuppressed or is on steroids, he or she should also be referred to the GP22.

Rash without fever or itching

Milia

Milia are one of the most common transient skin disorders in neonates; the condition is present in around 30–50% of neonates. These consist of 1–2mm white or yellowish papules on the face24; the nose is usually predominantly affected. Less commonly, the trunk and extremities are also involved. Milia are epidermal keratin cysts developing in connection with the pilosebaceous follicle25.

Neonatal milia does not require treatment as it spontaneously disappears within a few weeks24.

Source: Shutterstock.com

Erythema toxicum

Around half of all newborns develop a blotchy red skin reaction called erythema toxicum, usually at two or three days old. It is thought to be a benign condition that causes no discomfort to the infant24.

The lesions are firm, 1–3mm, yellow or white papules and/or pustules on a red swollen base. The lesions tend to be seen on the anterior and posterior trunk but may also be found on arms, legs and face25,26. On darker skin tones, the bumps may look brown, purple or grey instead of red27.

Erythema tends to last up to five to seven days and the lesions heal without any medical intervention24.

Source: CDC

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is a common, generally benign, contagious viral infection of the skin, which is caused by molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV). The condition is more prevalent in children, with the lesions involving the face, trunk, and extremities28.

Molluscum contagiosum produces a papular eruption of multiple umbilicated lesions. The individual lesions are discrete, smooth and dome shaped29. They are generally skin coloured with an opalescent character. The central depression or umbilication contains a white, waxy curd-like core. The size of the papule is variable, depending on the stage of development, usually averaging 2–6mm29.

Molluscum contagiosum is usually a self-limiting disease (usually within 6–18 months29), for which treatment is not mandatory. However, it is important not to squeeze the spots because the white substance contained within them is highly infectious, so there is an increased risk of the infection spreading to other parts of the body29.

Many treatments are painful, and this must be taken into consideration as molluscum contagiosum is a harmless (benign) and self-resolving condition30. Furthermore, it is thought that some treatments can increase the risk of scarring. There is no research evidence that any one treatment is better than others at clearing molluscum contagiosum. If treatment is deemed appropriate, topical therapies, such as salicylic acid and potassium hydroxide, may be recommended, or a surgical treatment, such as cryotherapy30.

Nappy rash

Persistent occlusion of the nappy area, resulting in overhydration and maceration of the epidermis, causes nappy rash. The defective epidermal barrier allows irritants from the urine and faeces to penetrate and initiate an irritant contact dermatitis. The inflamed skin is quickly colonised with Candida albicans31.

Convex surfaces closest to the nappy (buttocks, genitals, pubic area and upper thighs) tend to be red, with sparing (no redness) in the deeper flexures. The rash has a glazed appearance if acute, or fine scaling if more longstanding31. In babies with brown or black skin, nappy rash may cause the affected area to lighten. This is called post-inflammatory hypopigmentation and often clears up in a few weeks32.

Overhydration improves with nappy-free periods and frequent nappy changes. Barrier creams (e.g. zinc and castor oil) should be applied at each nappy change to protect the skin. However, if nappy rash is causing discomfort, a topical hydrocortisone cream (0.5% or 1%) should be considered for children aged one month or older for a maximum of seven days31. If candida infection is confirmed or suspected, a topical imidazole (e.g. clotrimazole or miconazole) should be prescribed and a barrier preparation should not be used until after the candidal infection has settled31.

Other rashes

Bacterial meningitis

Bacterial meningitis is an infection of the surface of the meninges33. It can affect anyone, but is most common in babies, children, teenagers and young adults33. Meningococcal disease and bacterial meningitis continue to have high mortality rates; around 1 in every 10 people affected dies34.

Healthcare professionals should be aware that classical signs of meningitis (neck stiffness, bulging fontanelle, high-pitched cry) are often absent in infants with bacterial meningitis35. Early non-specific symptoms of meningitis include fever, vomiting/nausea, lethargy, irritability, ill appearance, refusing food/drink, headache, aches and respiratory symptoms. Less common early symptoms include shivering, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and distention, coryza and ear, nose and throat symptoms33. Children suspected of having any symptoms of meningitis should be taken directly to hospital. Public Health England needs to be notified about all cases of suspected meningitis33.

General features of meningitis are non-blanching rash (anywhere on the body), altered mental state, shock, unconsciousness and toxic or moribund state. If a patient presents with these symptoms, the glass test should be used on the rash to confirm diagnosis (i.e. the side of a clear glass should be firmly pressed against the rash; if it does not fade under pressure, the patient may have septicaemia and needs urgent medical attention)33,36. However, a rash is not always present with meningitis and may be less visible in darker skin tones; therefore, it is important to also check the patient’s soles of feet, palms of hands and conjunctivae33.

The classic rash associated with meningitis usually looks like small, red pinpricks that spreads quickly over the body and turns into red or purple blotches. This type of rash does not fade under pressure of a clear glass. Medical advice should be sought immediately.

For children aged three months or less, treatment is intravenous cefotaxime plus amoxicillin or ampicillin33. Children aged over three months should be treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (or cefotaxime if co-administering calcium infusions)33. Patients may also need to be treated for shock with intravenous fluids and may be started on additional antibiotics and steroids depending on their diagnosis.

Conclusion

Prompt identification and management of rashes in children is vital to ensuring optimal outcomes, as these can range from self-limiting conditions to life-threatening emergencies. A systematic approach — considering the child’s age, medical history, accompanying symptoms and the characteristics of the rash — enables accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment.

Best practice

- Maintain a broad differential diagnosis and be vigilant for red flag symptoms, such as fever, lethargy, or systemic signs that may indicate serious underlying conditions;

- Involve parents or carers in monitoring progression and managing symptoms, providing clear guidance on when to seek further medical attention;

- Prioritise effective communication, ensuring families understand the condition, treatment options and follow-up requirements. Effective communication with families is essential to ensure understanding of the condition and its management, as well as when to seek further medical attention. By adopting a structured approach and using available resources, pharmacy professionals can provide timely and appropriate care, ultimately improving outcomes for children presenting with rashes.

This article is an updated version of ‘Rashes in children’, which has been reviewed and updated by the original authors Ashifa Trivedi and Vani Suri, to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in June 2017.

- 1.van Dorp F. Consultations with Children. InnovAiT: Education and inspiration for general practice. 2008;1(1):54-61. doi:10.1093/innovait/inm003

- 2.Slapped cheek syndrome. NHS Choices. Accessed February 2025. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Slapped-cheek-syndrome/Pages/Introduction.aspx

- 3.Increased parvovirus B19 activity in England and Wales. UK Health Security Agency . August 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/parvovirus-b19-activity-in-england/parvovirus-b19-activity-in-england#:~:text=Increasing%20levels%20of%20parvovirus%20B19%20activity%20in%20England,-Parvovirus%20B19%20causes&text=In%20recent%20years%20cyclical%20increases,2023%20and%20beginning%20of%202024.

- 4.Parvovirus B19 infection. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. February 2022. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/parvovirus-b19-infection/#!diagnosissub

- 5.Sachan D. Erythema infectiosum rash. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48(4):338. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21532111

- 6.Managing specific infectious diseases: A to Z. Slapped cheek syndrome (parvovirus B19). UK Health Security Agency. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-protection-in-schools-and-other-childcare-facilities/managing-specific-infectious-diseases-a-to-z#slapped-cheek-syndrome-parvovirus-b19

- 7.Chickenpox. NHS. Accessed February 2025. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Chickenpox

- 8.What Chickenpox Looks Like in Black People and Darker Skin Tones (With Images). GoodRx. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.goodrx.com/conditions/chickenpox/chickenpox-in-black-skin

- 9.Chickenpox. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/chickenpox#!topicsummary

- 10.Chickenpox: symptoms, treatment and potential complications. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2023. doi:10.1211/pj.2023.1.187371

- 11.Hand, foot, and mouth disease. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. September 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hand-foot-mouth-disease/#!topicsummary

- 12.What are the symptoms of hand, foot, and mouth disease? Healthline. February 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://www.healthline.com/health/hand-foot-mouth-disease#symptoms

- 13.BNF for Children. BNF for Children. Accessed February 2025. https://bnfc.nice.org.uk/

- 14.Vieira A, Wan Y, Ryan Y, et al. Rapid expansion and international spread of M1UK in the post-pandemic UK upsurge of Streptococcus pyogenes. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1). doi:10.1038/s41467-024-47929-7

- 15.Scarlet Fever. NHS. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/scarlet-fever/

- 16.NHS. Prickly heat. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/heat-rash-prickly-heat/

- 17.Atopic eczema. NHS . Accessed February 2025. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Eczema-(atopic)

- 18.Clinical guideline [CG57]. Atopic eczema in under 12s: diagnosis and management. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence . 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg57

- 19.Hives. NHS. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/hives

- 20.Urticaria. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/urticaria#!topicsummary

- 21.Ringworm. NHS. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/ringworm

- 22.Fungal skin infection — body and groin. National Institute of Health and Care. 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/fungal-skin-infection-body-and-groin#!topicsummary

- 23.Hainer B. Dermatophyte infections. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(1):101-108. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12537173

- 24.Rashes in babies and children. NHS. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/rashes-babies-and-children

- 25.Kansal N, Agarwal S. Neonatal milia. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52(8):723-724. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26388648

- 26.Berg F, Solomon L. Erythema neonatorum toxicum. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62(4):327-328. doi:10.1136/adc.62.4.327

- 27.All About Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum. WebMD. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.webmd.com/skin-problems-and-treatments/erythema-toxicum-neonatorum

- 28.Hanson D, Diven D. Molluscum contagiosum. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9(2):2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12639455

- 29.Molluscum contagiosum. NHS. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/molluscum-contagiosum/

- 30.Molluscum contagiosum. British Association of Dermatologists. 2025. Accessed February 2025. https://www.bad.org.uk/pils/molluscum-contagiosum/

- 31.Nappy rash. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/nappy-rash#!topicsummary

- 32.Diaper rash. Mayo Clinic. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diaper-rash/symptoms-causes/syc-20371636

- 33.Meningitis (bacterial) and meningococcal disease: recognition, diagnosis and management. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence . 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng240

- 34.Meningitis Research Foundation. Meningitis Research Foundation. Accessed February 2025. http://www.meningitis.org/

- 35.Meningitis. NHS. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/meningitis/

- 36.Case-based learning: meningitis. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2019. doi:10.1211/pj.2019.20206581