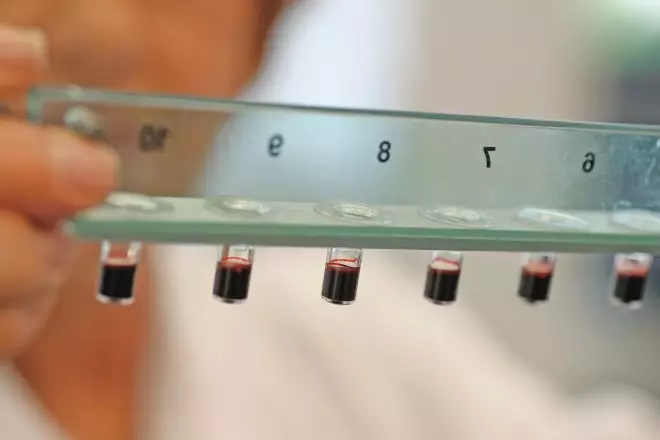

Dr. Randal J. Schoepp / Wikimedia Commons

Ebola virus disease

Source: Wikimedia Commons

A worm-like virus discovered in 1976 dominated the headlines in 2014. The worst outbreak of the fatal haemorrhagic Ebola virus disease started in the West African country Guinea, infected 17,942 individuals and killed 6,388 people as of 16 December.

Although the first Ebola cases were reported in March, it was in August that the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, followed by a roadmap to scale up the response to the disease.

Pharmacists in Africa said the outbreak had gone beyond the “capacity and responsibility of any single government”.

An international effort involving regulators, governments and pharmaceutical companies has scrambled to fast-track experimental vaccines and treatments, but no products have been licensed as yet. Two recombinant vaccines, which are being evaluated in Phase I trials, show promise: GlaxoSmithKline’s chimpanzee adenovirus serotype 3 vaccine (ChAd3) and NewLink Genetics Corp/Merck Sharpe Dohme’s Ebola vaccine, which uses an attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV). A third vaccine, being developed by Johnson & Johnson, has shown promise in non-human primate studies.

ZMapp, a cocktail of three monoclonal antibodies, caught the imagination of the world as a possible Ebola therapy, but was hampered by its limited supplies. Its clinical effectiveness is still unclear, although it successfully cleared Ebola virus infection in monkeys, paving the way for human trials.

One issue yet to be addressed is how any Ebola vaccines and treatments will be priced to ensure adequate access to medicine for all those in need.

Read more on The Ebola virus disease

E-cigarettes on the shelves

Source: Shutterstock.com

Despite inconclusive evidence on whether e-cigarettes are safe to use, there is a mass movement towards their use with around 2.1 million people in Great Britain now described as ‘vapers’. In February, news that two major pharmacy chains were stocking e-cigarettes sparked a debate about whether a pharmacist should be selling a potentially harmful recreational drug. In July, an investigation by Public Health England and the Trading Standards Institute found that some retailers, including pharmacies, were selling the devices to teenagers, some aged as young as 13 years. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society and the UK’s four chief pharmaceutical officers advised against the use of e-cigarettes as smoking cessation aids, preferring to promote the use of licensed nicotine-containing products.

In August, the World Health Organization called for tough new regulations, including a ban on their use in indoor public places and stopping all sales to children. Research is still ongoing on the benefits and risks of e-cigarettes.

Public access to clinical research data

Source: BasPhoto / Shutterstock.com

In October, after a long consultation process, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) issued an eagerly anticipated decision to publish clinical trial reports for each medicine it reviews. Such reports are part of its commitment to improve transparency and access to data from clinical trials and adverse drug reaction reports.

The EMA was criticised over its draft policy when it initially revealed that the public would only be able to access read-only versions on screen. A range of organisations called on the EMA to rethink its plan and make the data freely available to enable independent researchers to properly scrutinise the safety and efficacy of medicines. The EMA obliged and will make clinical reports available to download sometime in 2015, albeit with some caveats.

An EMA consultation on access to adverse drug reaction (ADR) reports in the EudraVigilance database also raised eyebrows during the year when scientists accused the regulator of censorship. The EMA proposed that it view any research paper that uses the ADR data before submission for publication.

Roche’s anti-influenza drug, Tamiflu (oseltamivir), which was stockpiled by governments in case of a possible pandemic — the UK spent £424m — became exhibit A for an allegedly flawed drug regulatory system. After a four-year battle, researchers were able to access full clinical trial data, concluding that although the antiviral provided small benefits on symptom relief, there was little evidence it reduced hospital admissions or the risk of developing pneumonia.

Regulator gets tough

Source: Dave Porter / Alamy

Pharmacists will look back on 2014 as the year that the government and the professional regulator offered them very little carrot but a lot of stick. Government promises to decriminalise dispensing errors, as part of the ongoing medicines legislation overhaul, were repeatedly delayed — first in July and then again in September when health minister Earl Howe (pictured) admitted: “Nobody regrets that more than I do.” Despite his words, a month later community pharmacists in England were told that in future their pharmacy must be named in any patient safety incident reported to the National Reporting and Learning System as part of changes to the community pharmacy contact. That announcement — in the name of transparency — was followed in November by proposals to change the law so that pharmacists could face a fitness-to-practise hearing if their lack of written or spoken English posed a threat to patient safety.

These get tough measures came at the same time that pharmacy inspections showed the majority of pharmacists were meeting standards laid down by the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC). In November, a year after the GPhC’s new pharmacy premises inspection model was introduced, a survey revealed that more than 90% of premises were “satisfactory”. While there was disappointment that few were ranked “good” or “excellent”, it was proof that pharmacists are achieving the professional standards expected of them.

The autumn brought disappointment over the government’s decision not to cap the number of UK pharmacy students, despite the results of a 2013 Higher Education Funding Council consultation, which found the majority were in favour of some form of student intake control.

The year ended with a stark warning in a report commissioned by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society that the UK government’s ambition to develop pharmacy’s caring role was thwarted unless pharmacy funding is changed, and pharmacy learns to speak with one voice.

Pharmacy projects look for evidence

Source: Boots

Community pharmacy services could save the NHS £470m each year

There is a need for greater evidence to properly assess the merits of pharmacy services to patients. One effort to address this is a collaboration between four pharmacy multiples as part of the Community Pharmacy Future project. Results released in March suggest that providing three services through community pharmacy — a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) case finder service, a COPD support service and a support service for patients taking four or more medicines — improves patient outcomes and could save the NHS £470m per year if rolled out across England.

The focus on savings rather than efficacy is perhaps regrettable but is a reflection of the financial situation of the NHS — the biggest customer of pharmacy services in the UK.

In Liverpool, a tripartite collaboration between pharmacy chain Lloydspharmacy, a major NHS hospital trust and John Moores University, thought to be the first of its kind in the UK, has seen the formation of a Centre for Pharmacy Innovation. The initiative will test a new model of care designed to improve the transfer of patients between secondary and primary care and provided by community pharmacy.

New opportunities for individual pharmacists in the UK to develop clinical skills arose in 2014; those with at least one year’s experience can now apply for government funding from an existing training programme run by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), previously open to 16 other healthcare professional groups.

These developments should help to normalise academic partnerships within the sector and will ultimately ensure that pharmacy practice is evidence-based and supports better patient care.

Deal makers and breakers

Source: Shutterstock.com

Pfizer backs away from AstraZeneca

The year saw major mergers and acquisitions involving the top three pharmacy players in the UK, while pharmaceutical companies made more moves than signed deals.

Novice player Bestway Group entered the UK pharmacy market in a £620m deal struck in July. Known for a mixed bag of businesses, it bought 770 pharmacies run by Co-operative Group, the third largest pharmacy chain in the UK. US corporations were making moves for their European counterparts throughout the year. In August, the iconic American retailer Walgreens cemented its relationship with Europe’s largest wholesaler-pharmacy chain Alliance Boots by buying the remaining 55% stake of the private company with US$5.3bn in cash and 144.3 million shares, totalling $15bn. This followed a 2012 agreement, when Walgreens bought a 45% stake in the chain. Walgreens Alliance Boots will have 11,000 pharmacies across ten countries.

Celesio, the wholesale-retail parent company of the second-largest UK pharmacy chain Lloydspharmacy, was acquired by the US wholesaler McKesson in December. This came after some complexity after the initial offer was called off in January. The McKesson and Celesio tie-up will have operations in more than 20 countries, including a network of more than 12,000 pharmacies.

The £65bn acquisition bid by US pharmaceutical giant Pfizer for AstraZeneca would have made it the biggest ever takeover of a UK firm by a foreign company had it gone ahead. In April, Pfizer made its move for tax reasons, but the deal was off the table by June on the back of heightened concerns about how the merger would affect the UK research and development base and drug development.

Come October, the proposed £32bn merger of AbbVie, a US pharmaceutical company, with Shire, based in Dublin, was called off.

Pharmacists push for greater clinical role

Source: Jack Sullivan / Alamy

Early in 2014, the UK health secretary Jeremy Hunt signalled his support for giving community pharmacists in England access to the summary care record (SCR) — an electronic summary of a patient’s medical record. News soon followed of a pilot scheme run by NHS England giving community pharmacists in 100 pharmacies in five areas of England access to the SCR. A separate pilot scheme, with £1.8m provided by the Prime Minister’s challenge fund, will give pharmacists access to medical records to treat common conditions, such as eye infections or upper respiratory tract infections. In November, it was confirmed that patients would gain access to their health records, alongside access by all healthcare providers. But warning shots have been fired by lawyer Noel Wardle, a partner at Charles Russell Speechlys, who says that access to patient information could open up pharmacists to legal challenges.

Pharmacists and pharmacy organisations in England seized upon the Department of Health’s ‘Call to action’ consultation on community pharmacy. More than 800 submissions were received by the DH in anticipation of a new strategy for the sector. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society called for a more clinically focused community pharmacy contract along with pharmacy access to patient records, recurring themes among submissions.

The government’s response has been something of a damp squib — reported to be contained within NHS England’s five year plan, its vision for overhauling NHS service provision to make it more patient-focused and efficient, but with only a few mentions of pharmacy.

In Wales, the Welsh Pharmaceutical Committee — an advisory group to the Welsh government — collaborated with stakeholders to produce a strategy for pharmacy. Practitioners were rewarded with a vision that places pharmacy teams at the heart of NHS services, with an emphasis on electronic pharmaceutical care plans.

In Scotland, scrutiny by the Scottish parliament’s Health and Sport Committee and concerns raised by community pharmacy leaders threatened to stall implementation of the government’s 2013 Prescription for excellence plan. But the strategy survived, with the government intent on helping pharmacists acquire the necessary clinical skills to deliver the far-sighted plan.

Persistent demands from pharmacists for pharmacy services to be positioned at the centre of primary care appear to be gaining traction, with the cementing of the new medicine service (NMS) and the discharge medicines review service within the community pharmacy contractual frameworks in England and Wales, respectively.

The NMS was subjected to an evaluation by academics based at the University of Nottingham and University College London. Their randomised controlled trial determined that the service was cost effective and increased the number of patients who are adherent to their treatment by about 10%. This was enough to persuade NHS England to continue funding the service indefinitely.

But still many of the conversations about making the most of pharmacists’ skills were not backed by action. Calls to commission a national common ailment scheme in England, as has been achieved in Scotland and Wales, were still being heard as the year drew to a close, despite repeated warnings that the NHS needs to make better use of its primary care practitioners if it is to cope with urgent and emergency care demands.

Into the clinic

Source: dpa picture alliance archive / Alamy

NICE highlighted the value of newer anticoagulants

In April, the World Health Organization (WHO) described Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as a major threat to public health in a report that called for co-ordinated action to halt a “post-antibiotic era”. During the World Health Assembly, a month later, WHO upped the ante by saying it would prepare a draft global plan to tackle AMR, which will be presented to the assembly’s 2015 gathering.

Despite the increasing urgency over the lack of antibiotics in the development pipeline, in 2014 several medicines came on to the market that target infectious diseases.

Telavancin was the first lipoglycopeptide antibiotic to gain marketing authorisation in Europe and is expected to be followed in 2015 by oritavancin and dalbavancin.

Telavancin (Clinigen’s Vibativ) offers a treatment option to patients who have contracted pneumonia in hospital, caused by meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The lipoglycopeptide antibiotic has a dual mechanism of action: it binds to and prevents polymerisation of bacterial cell wall constituents, weakening and then killing the cell, as well as interacting with the cell membrane, causing depolarisation — again leading to cell death.

Oritavancin and dalbavancin — used to treat patients with skin infections — were approved for use in the United States. The US Food and Drug Administration had granted both drugs qualified infectious disease product (QIDP) status, allowing for priority review.

Another new player in the infectious diseases arena was bedaquiline (Janssen’s Sirturo), the first agent approved specifically for tuberculosis (TB) in four decades. When the medicine was licensed in the United States in December 2012, the TB Alliance called the move “historic” — now patients with multi-drug resistant TB in the UK can benefit from the treatment.

In virology, sofosbuvir (Gilead’s Sovaldi) was the first of three new hepatitis C drugs to hit the market and raised hopes for a cure in patients infected with the virus. It made its mark by becoming the first hepatitis C drug that does not need to be given with interferon. Its active metabolite is an inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase.

Simeprevir (Janssen’s Olysio) came along next and is a second-generation protease inhibitor that targets the NS3/4A serine protease of hepatitis C.

It has a simpler dosing regimen and fewer side effects than the currently used first-generation protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir.

A third hepatitis C drug, daclatasvir (Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Daklinza), followed sofosbuvir and simprevir. It is estimated to cure chronic hepatitis C infection in up to 99% of cases when used in combination with other drugs. Daclatasvir is an inhibitor of the non-structural protein 5a (NS35a).

Nice moves

Other notable clinical developments in 2014 included the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) judgement on statin therapy. Its cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention guidelines now recommend that all patients with a 10% or greater risk of developing CVD over the next ten years should be offered atorvastatin 20mg for primary prevention. This cut the threshold by half, making an extra 4.5 million patients in England eligible for statin therapy, and caused debate among clinicians about the medicalisation of healthy individuals and the incidence of adverse events associated with statin use.

NICE also endorsed the NHS use of eculizumab (Alexion’s Soliris), described as a significant breakthrough in the management of aHUS (atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome) and touted as the world’s most expensive drug with an annual cost of around £340,000 per patient in the first year and around £330,000 thereafter.

NICE made significant updates to its clinical guidelines on bipolar disease and atrial fibrillation. For bipolar depression, it ruled that fluoxetine is the only effective antidepressant, and only in combination with the atypical antipsychotic olanzapine. The updated guideline also recommended specific antipsychotics for the manic episodes of the disorder, no longer recommending the drug class as a whole. And in the management of atrial fibrillation, NICE highlighted the value of the newer anticoagulants — apixaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Spotlight on dementia

The UK’s Medical Research Council launched the world’s largest dementia study in June, gathering data from two million volunteers to improve the dementia treatment and prevention.

GPs in England were encouraged to improve diagnosis rates, with practices receiving £55 for each patient diagnosed with dementia, a policy that was widely criticised. And in Scotland, prescribers were brought to task for their continued reliance on the use of antipsychotic drugs to manage dementia patients.

A study published in The BMJ attempted to disentangle the complicated relationship between use of benzodiazepines and development

of dementia by looking at use of the drugs at least six years before a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. It found that older adults who are prescribed benzodiazepines for longer than three months were up to 50% more likely to develop this form of dementia. Interpretation of the results is, however, fraught with uncertainty — and the link is not necessarily causal.

Domperidone displaced

In September, the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency announced that the antiemetic domperidone was to become a prescription-only medicine and gave pharmacies 48 hours to remove the product from their shelves. A European Medicines Agency (EMA) review found that the drug, a dopamine antagonist, was associated with a small increased risk of serious cardiac side effects.

You may also be interested in

Top ten features of 2025

Learning and CPD: 2025 in review