Fanatic Studio / Alamy Stock Photo

Alcohol addiction is a devastating disease. In the UK, an estimated 9% of men and 4% of women show signs of alcohol dependence, which costs the NHS £3.5bn per year. The disease is similarly pervasive in the United States, where alcohol use disorder is estimated to affect 13.9% of adults at a societal cost of more than US$249bn a year.

As well as changes in mood and behaviour, long-term alcohol abuse can lead to hypertension and heart disease, a variety of liver problems, pancreatitis and the development of several cancers.

Four treatments are specifically licensed for alcohol addiction in the UK — disulfiram, naltrexone, acamprosate and nalmefene — which, apart from nalmefene, are also licensed in the United States[1]

.

But these treatments are often contraindicated and do not cover the full complexity of addiction, says Lorenzo Leggio, chief of the clinical psychoneuroendocrinology and neuropsychopharmacology laboratory, which is jointly funded by the US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. “We need more medicines for these patients… If you only have three to choose from, you are missing an opportunity to treat people who might respond to another medicine.”

We need more medicines for these patients… If you only have three to choose from, you are missing an opportunity to treat people who might respond to another medicine

Our understanding of the underlying neurobiology of alcohol addiction has grown dramatically in the past few decades. And with this understanding comes a wealth of new possible drug targets and the potential of prognostic and diagnostic markers to help doctors match the right treatment with the right patient. There are, however, big hurdles to overcome in translating laboratory evidence and theory into effective treatments.

Three-stage cycle

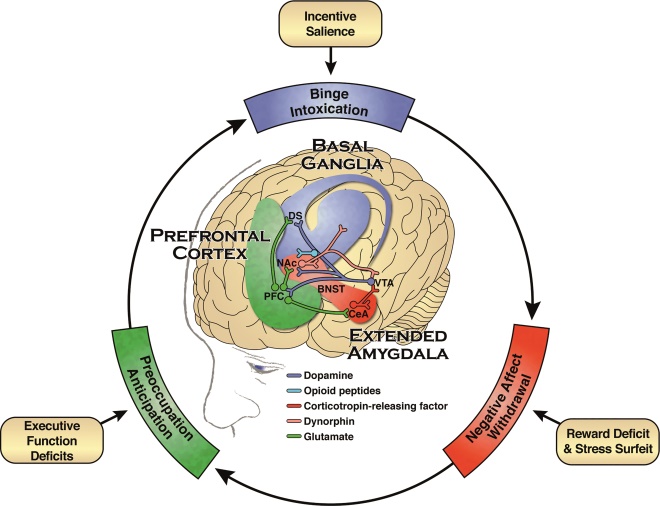

A host of environmental and genetic factors interact and overlap with multiple neurobiological pathways in the development of alcohol addiction. The NIAAA describes a three-stage cycle — each stage is underpinned by different but interacting pathways in the brain.

First, there is a loss of control in limiting alcohol intake, followed by a negative emotional state in the absence of alcohol or withdrawal, and finally a compulsion to seek out and consume alcohol.

Three-stage cycle of alcohol addiction

Source: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Draft strategic plan for research 2017–2021.

Alcohol addiction is characterised by a three-stage cycle involving loss of control over alcohol intake (binge/intoxication stage), a negative emotional state in the absence of alcohol (withdrawal/negative affect stage) and a compulsion to seek out and consume alcohol (preoccupation/anticipation stage). Each stage is mediated by three distinct but interacting neurobiological circuits involved in the experience of reward and habit formation (the basal ganglia), stress (the extended amygdala) and executive function (the prefrontal cortex).

Key:

DS = dorsal striatum

NAc = nucleus accumbens

PFC = prefrontal cortex

VTA = ventral tegmental area

BNST = bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

CeA = central nucleus of the amygdala

Alcohol affects signalling systems involving the neurotransmitters glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), dopamine, and serotonin. Endogenous opioids are also affected, as well as corticotropin-releasing factor, which activates the brain’s response to stress. Neuroimmune and neuroendocrine signalling is also thought to play a part. These systems adapt to chronic heavy drinking, leading to changes in reinforcement, increased anxiety, and heightened sensitivity to stress.

“There are so many routes to alcohol addiction and so many parts of the brain that can be involved,” explains George Koob, director of the NIAAA.

Source: Courtesy of George Koob

George Koob, from the US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, says there are so many routes to alcohol addiction and so many parts of the brain that can be involved

The institute’s focus is identifying how changes in these pathways contribute to alcohol addiction, how that links to other substance abuse, and how the pathways might be modified to help patients to recover.

In November 2016, the NIAAA put out a consultation for its five-year strategic plan for research, of which a principal goal is to develop and improve treatments for alcohol use disorder, as well as to improve access to treatments[2]

. The agency is currently supporting studies of more than 30 promising treatments[3]

.

Ultimately, the NIAAA hopes to develop a much wider range of medicines that, alongside psychosocial therapy, offer better options for patients. “I don’t think there’s going to be any one treatment that cures addiction,” says Koob. “Sometimes the same person drinks for many different reasons.”

I don’t think there’s going to be any one treatment that cures addiction. Sometimes the same person drinks for many different reasons.

Limited options

The oldest treatment for alcohol addiction, disulfiram (Antabuse), inhibits acetaldehyde dehydrogenase — an important enzyme involved in breaking down alcohol in the liver — and, if taken with even small amounts of alcohol, produces unpleasant side effects, including vomiting, dizziness and palpitations.

In the 1990s, healthcare professionals began prescribing naltrexone, an opioid-blocking drug for alcohol addiction after several studies showed that, alongside psychosocial therapy, it reduced the rate of relapse by diminishing the pleasurable effects of alcohol or ‘craving’[3]

. Naltrexone is thought to do this through the dopaminergic pathway, which is involved in risk–reward feedback in the brain.

A decade later, acamprosate (Campral; Merck) was added to the treatment list. The drug has also been shown to give some benefit for patients who need help dealing with cravings for alcohol once they stop drinking[4]

. Acamprosate is believed to mimic certain neurotransmitters in the brain and likely works to stabilise signalling that has gone awry owing to alcohol withdrawal.

The most recent addition is another opioid antagonist, nalmefene (Selincro; Lundbeck), which was approved in Europe in 2013, but is not yet approved in the United States for alcohol addiction. Unlike the others, it can be taken ‘as needed’ when the person feels the urge to drink. The drug was made available on the NHS in 2014 to help problem drinkers cut down their alcohol intake, but its use has been controversial. Some studies have reported limited effectiveness and that it works no better than counselling. And some researchers have questioned the regulator’s decision to license the drug and suggested that company-sponsored trials were poorly designed[5],

[6]

.

Anne Lingford-Hughes, deputy head of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and a consultant psychiatrist at Central North West London NHS Foundation Trust, says nalmefene has a place for people who are not highly dependent but are trying to reduce their drinking and who are also receiving counselling. But she adds: “It is a tricky drug to use because of the side-effect profile.”

Overall, medicines for treating alcohol misuse are not widely used. Data suggest that in the United States and the UK, only 5–10% of patients are treated for alcohol addiction, despite treatment being recommended for most patients with moderate dependency.

Jonathan Chick, consultant psychiatrist and medical director, Castle Craig Hospital, Scotland, points to an NHS survey which found that only 6% of people who say they have alcohol dependence are prescribed medicines for the condition. “Whereas many get antidepressants and tranquillisers for which there is no evidence,” he says.

Source: Courtesy of Jonathan Chick

Jonathan Chick, consultant psychiatrist and medical director, Castle Craig Hospital, Scotland, says only 6% of people with alcohol dependence are prescribed medicines for the condition

It could be argued this lack of use is due partly to the shortcomings and limitations of the treatments available, but there is also a cultural issue, say Koob and Lingford-Hughes.

“In the clinic, you have some people who don’t believe medicines should be used at all,” says Lingford-Hughes. She explains that some people don’t have any training and addiction teams have been “decimated” owing to funding cuts, so people who feel comfortable prescribing are disappearing fast. “We had alcoholics asking for nalmefene and no one knew what they were talking about,” she adds.

In the clinic, you have some people who don’t believe medicines should be used at all

Hype or cure?

The lack of treatment options has led both doctors and patients to seek out alternatives, and baclofen — a selective agonist for the GABA-B receptor that is used to treat multiple sclerosis — is perhaps the most well-reported drug currently being investigated for alcohol addiction.

Baclofen stands out because of its unusual back story and the evangelical zeal with which supporters say it eliminates alcohol cravings. Alcohol is thought to have a similar effect on the GABA neurotransmitter in the brain: binding to its receptors and inhibiting signalling. So baclofen, in theory, should help reduce the ‘craving’ for alcohol. French cardiologist Olivier Amiesen tested this theory on himself and published a best-selling book charting how he cured his addiction with high doses of the drug. A subsequent rise in off-label prescribing of baclofen for alcohol addiction prompted multiple clinical trials.

In September 2016, the results of three clinical trials were unveiled at the World Congress for Alcohol and Alcoholism in Berlin. In the Bacloville study — in which 320 patients were under routine GP care and were allowed to continue drinking — 57.8% of those given baclofen either stopped completely or cut down to “normal levels” compared with 36.5% who were given a placebo[7]

. However, in the Alpadir study, which included 320 patients in specialist treatment, there was no significant difference between baclofen and placebo groups; 11.9% of patients on baclofen achieved 20 weeks of continuous abstinence compared with 10.5% on placebo[8]

.

A third, Dutch, study presented to delegates and published in European Neuropsychopharmacology in 2016 also found no difference between patients in the baclofen and placebo groups, although both had markedly high success rates thanks to the intensive psychosocial support in place[9]

.

These trials follow a German study published in 2015, which showed significantly increased rates of abstinence with the use of baclofen[10]

.

Most addiction experts, at least outside France, are awaiting more data before reaching any conclusions, says Lingford-Hughes. She adds that a better understanding of why the results have been inconsistent will be crucial to realising baclofen’s use in the clinic.

Source: Courtesy of Anne Lingford-Hughes

Anne Lingford-Hughes, deputy head of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and a consultant psychiatrist at Central North West London NHS Foundation Trust, says most addiction experts, at least outside France, are awaiting more data on bacofen before reaching any conclusions

“There is variability and we need to understand more and do more work to inform why they’re not showing a dose response,” she says, adding: “The Dutch study was clear that having a substantial psychosocial aspect wiped out the medical effect but you wouldn’t get that in the UK because that level of support is just not available.”

There is variability in the baclofen studies and we need to understand more and do more work to inform why they’re not showing a dose response

Baclofen is not the only drug that targets GABA-mediated pathways being investigated — gabapentin is among those being studied. Already used in the treatment of epilepsy and neuropathic pain, gabapentin is thought to work as a calcium channel blocker, which has knock-on effects on GABA production in the brain. Preclinical studies have suggested that gabapentin “normalises” the stress-induced activation of GABA seen in the amygdala of patients who are alcohol dependent[11]

.

An NIAAA-funded trial of 150 alcohol-dependent patients published in 2014 showed positive results with a high dose of 1,800mg of gabapentin[11]

. In 2015, the NIAAA began a clinical trial of gabapentin enacarbil — an extended release version of the drug — due to complete in early 2017.

Topiramate, an anti-seizure medication now being tested in alcohol dependence, also acts on GABA receptors as well as other neural signalling pathways. One study found it may have a role in helping heavy drinkers to cut down, especially those with a specific gene variation[12]

.

Novel targets

Some researchers are starting to examine pathways not traditionally linked with the disease to identify new drug targets and expand the available treatments for alcohol addiction. Leggio is one of them. “We are looking at the interaction between the gut and the brain. We know there are a lot of signals from the gut to the brain and [the] brain to the gut, and there is an overlap between feedback regulation for alcohol addiction and appetite.” The so-called “hunger hormone”, ghrelin, is one such target.

We are looking at the interaction between the gut and the brain… there is an overlap between feedback regulation for alcohol addiction and appetite

“We are doing a study on a drug that antagonises the receptor for ghrelin and could treat alcohol disorder,” says Leggio. “We are also doing some research into oxytocin and we are looking into the gut microbiome where there have been links with anxiety and depression but not yet a lot of work on addiction.”

Source: Courtesy of Lorenzo Leggio

Lorenzo Leggio, chief of the clinical psychoneuroendocrinology and neuropsychopharmacology laboratory, jointly funded by the US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, is looking at the interaction between the gut and the brain to try to identify new drug targets for alcohol addiction

He points to intriguing evidence from patients undergoing bariatric surgery for obesity who have been shown to have an increased risk of developing alcohol addiction. One theory suggests specific metabolic and hormonal changes triggered by gastric bypass surgery are to blame.

Another novel target being investigated is the neuropeptide vasopressin. A recently completed NIAAA phase II study reported positive results for a new compound ABT-436, which has been designed to block vasopressin, and, in doing so, help to regulate brain circuitry involved in emotion, particularly stress and anxiety. In a randomised clinical trial of 144 alcohol-dependent patients, those who had reported high levels of stress appeared to respond better to ABT-436, suggesting a potential role in people with alcohol addiction who also suffer from anxiety[13]

.

Yet the stumbling block for new treatments may not be a lack of new targets but the cost. For a new central nervous system compound, the route from discovery to market takes approximately 18 years and costs more than US$1.8bn.

“There are two valleys of deaths for new treatments. The first is getting an investigational new target through the Food and Drug Administration. The second is a positive clinical trial, which requires input from multiple sites and that can cost anything from US$10m–$30m,” says Koob.

The NIAAA strategy proposes more efficient target identification, better support for small independent laboratories in moving research from animal studies into human testing, and setting up research networks to speed up clinical trials.

“We are trying to short-circuit some of these barriers [of getting a new drug to market] by triaging along the way,” explains Koob. “We are not going to cure addiction by throwing a drug at somebody. But all of psychiatry needs additional medicines and better medicines.”

We are not going to cure addiction by throwing a drug at somebody. But all of psychiatry needs additional medicines and better medicines

Leggio believes that the future of treating alcohol addiction will not only be about identifying new drug targets, but also being able to predict which treatment would work best in which patient. Researchers don’t yet know enough about the underlying biology or genetics to make this a reality but studies have started to include work on identifying subgroups of patients who respond better.

Chick agrees that more specific tailoring of drugs will be essential. “Perhaps based on other mental symptoms, genes or type of evolution of the disorder, and misuse of accompanying other substances,” he says.

“We’re not going to find a single factor that will predict a response to any drug,” says Leggio. “Some day we could do genetic testing but the predictors could also be psychological markers, family history or bioimaging markers. You could scan a patient with fMRI to give an idea what would be the best treatment for them. This is the challenge for the future.”

References

[1] Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S et al. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;12:CD001867. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001867.pub2

[2] National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Draft strategic plan for research 2017–2021. Available at: www.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/DraftSP/NIAAA_Draft_Strategic_Plan_11_04_16_final.pdf (accessed March 2017)

[3] Litten RZ, Wilford BB, Falk DE et al. Potential medications for the treatment of alcohol-use disorder: an evaluation of clinical efficacy and safety. Subst Abuse 2016;37:286–298. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1133472

[4] Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S et al. Acamprosate for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;9:CD004332. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004332.pub2

[5] Palpacuer C, Laviolle B, Boussageon R et al. Risks and benefits of nalmefene in the treatment of adult alcohol dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished double-blind randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001924. eCollection 2015

[6] Fitzgerald N, Angus K, Elders A et al. Weak evidence on nalmefene creates dilemmas for clinicians and poses questions for regulators and researchers. Addiction 2016;111:1477–1487. doi: 10.1111/add.13438

[7] Jaury P. High-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol drinkers (Bacloville). ISBRA ESBRA Berlin 2016. Available at http://isbra-esbra-2016.org/essential_grid/high-dose-baclofen-for-the-treatment-of-alcohol-drinkers-bacloville-clinicaltrials-gov-identifier-nct01604330/ (accessed March 2017)

[8] Reynaud M. A randomized double blind placebo controlled efficacy study of high-dose baclofen in alcohol dependent patients: The Alpadir study. ISBRA ESBRA Berlin 2016. Available at http://isbra-esbra-2016.org/essential_grid/a-randomized-double-blind-placebo-controlled-efficacy-study-of-high-dose-baclofen-in-alcohol-dependent-patients-the-alpadir-study/ (accessed March 2017)

[9] Beraha EM, Salemink E, Goudriaan AE et al. Efficacy and safety of high-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2016;26;1950–1959. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.10.006

[10] Müller CA, Geisel O, Pelz P et al. High-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence (BACLAD study): A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015;25:1167-1177. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.04.002

[11] Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V et al. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med2014; 174:70–77. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11950

[12] Kranzler HR, Covault J, Feinn R et al. Topiramate treatment for heavy drinkers: moderation by a GRIK1 polymorphism. Am J Psych 2014;171:445–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13081014

[13] Ryan ML, Falk DE, Fertig JB et al. A phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial assessing the efficacy of ABT-436, a novel V1b receptor antagonist, for alcohol dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016; doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.214 [Epub ahead of print]