Key points

- Front-line acute clinical services need new models of workforce development to maintain clinical services.

- Advanced trained clinical pharmacists have potential to support clinical management of patients attending emergency departments.

- Clinically enhanced pharmacist independent prescriber courses are successfully being delivered and support the advanced clinical role of pharmacists.

Introduction

With an increasingly ageing population, presenting with ever more complex health needs, comes the need to radically rethink service provision and the way the ‘front-line’ clinical workforce is deployed. This has recently been acknowledged by a number of influential bodies. The 46th House of Commons Emergency Admissions to Hospital report (2013–2014) noted that “the health sector does not consistently work together in a cohesive way to secure savings, better value and a better service for patients”[1]

, while the Care Quality Commission (CQC) State of Care report from the same year added that “more than half a million people aged 65 and over are admitted as an emergency with ‘avoidable’ conditions that potentially could have been managed, treated or prevented in the community”[2]

.

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine states that “around 500 patients died in 2014 as a direct result of emergency departments (EDs) becoming overcrowded and almost 350 of the deaths were among patients who had not been diagnosed or given medical treatment quickly enough.”

The NHS is currently facing a range of complex pressures, including an ageing and increasingly diverse patient population, coupled with challenges in recruiting sufficient numbers of doctors in emergency medicine (EM) and general practice[3]

. These challenges require nothing less than a system-wide re-design and a departure from traditional thinking. One key change involves developing and supporting a stable and sustainable non-doctor, clinical workforce, to complement the medical workforce and allow for a ‘cross-fertilisation’ of knowledge, practices and ideas.

The ‘NHS England five year forward view’ emphasised the need for integrated out-of-hospital care based on general practice (multispecialty community providers), aligning general practice and hospital services (primary and acute care systems), and closer alignment of social and mental health services across hospital and community health settings[4]

. The King’s Fund further underlined this position, suggesting that such ambitions would “… require a workforce that reflects the centrality of primary and community care and the need for more generalism; is able to deliver increased co-ordination across organisational boundaries; and can address inequalities in treatment and outcomes across physical and mental health services”[5]

.

Sources and selection criteria

The sources selected for this report relate to the ‘Pharmacists in Emergency Departments (PIED)’ suite of studies and the related clinical training strategy adopted by Health Education England (HEE), the organisation responsible for NHS workforce training and development in England, for pharmacists. Each are discussed below and how they contribute to the understanding and adoption of pharmacist advanced clinical training and future roles.

Published evidence

Although a number of locally isolated examples of good practice in UK EDs and urgent care settings exist (e.g. Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London[6]

; Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge[7]

; and Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust, London[8]

), there is little published evidence to support the role of pharmacists practising clinically in these settings. Results from a study by Ahmed et al. suggest that pharmacists might manage up to 5% of ED attendees, although the authors note that the majority of these were minor cases[9]

. Published literature examining the role of clinical pharmacists in EDs (based on a UK 40-hospital site questionnaire in 2008) demonstrated that pharmacists were supporting clinicians with guideline development and review, patient group directions, provision of training, provision of advice and drug history taking[10]

. Recent evidence from conference proceedings at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Foundation Trust demonstrated that clinical pharmacists in the ED have been used for: allergy confirmation; providing a medicines safety barrier supporting safer prescribing in a high-risk environment; reduction in missed or delayed doses through early drug history identification; medicines reconciliation and supply of non-stock medicines; avoidance of adverse drug reactions; and provision of specific timely drug advice[6]

. This evidence shows that the role of the clinical pharmacist in the UK is and has been primarily concerned with pharmaceutical care and medicines optimisation, as opposed to truly integrating and supporting clinicians with managing clinical cases that are admitted into the ED.

Internationally, pharmacists also work in EDs, however, although they are known as ‘hospital’ or ‘clinical’ pharmacists, their roles are limited to pharmaceutical care, review of medical care, or optimisation of medication, and the role of the clinical pharmacist, mirroring that of a ward pharmacist who is present in the setting to screen physician orders and ensure medication safety[11]

. The American College of Emergency Physicians policy statement on clinical pharmacist services states that “… clinical pharmacists serve a critical role in ensuring efficient, safe and effective medication use in the ED and [the College] advocates health systems to support dedicated roles for pharmacists within the ED. The EM pharmacist should serve as a well-integrated member of the ED multidisciplinary team who actively participates in patient care decisions, including resuscitations, transitions of care, and medication reconciliation to optimize pharmacotherapy for ED patients”. The policy statement also acknowledges variability in how this is delivered depending on the nature of the hospital[12]

.

Other than the United States, other countries such as Canada[13]

, Denmark[14]

, Australia[15]

and Qatar[16]

have also introduced and studied the implementation of ED pharmacists. In 2012, a reported case detailed that of a pharmacist who worked between an ED department and a primary care network in Canada. This pharmacist worked part time in the primary care setting and part time in the emergency setting, providing pharmaceutical care and timely communication of information to ensure seamless care, especially in the older population, to reduce emergency admissions[13]

. Services described in Denmark, Australia and Qatar involved pharmacists taking medication histories, medication reconciliation, ensuring medication prescribing accuracy, as well as roles that constitute pharmaceutical care, rather than clinical assessment[14],[15],[16]

.

The Nuffield Trust states that “equipping NHS nursing, community and support staff with additional skills to deliver care is the best way to develop the capacity of the health service workforce, and will be vital to enable the NHS to cope with changed patient demand in the future. However, expanding the skills of the non-medical workforce in this way also presents big organisational challenges for NHS Trusts, and will not be easy to achieve in the current financial context. Despite this, changing staffing should be considered an urgent, ‘must-do’ priority” [17]

.

As a result of the lack of evidence nationally and internationally regarding pharmacists clinically managing patients, HEE West Midlands (HEE-WM) and its national partners began a three-year research programme in 2013[18]

. This programme aimed to test and justify the development of clinical pharmacist roles across primary, secondary, community, and urgent, acute and emergency care settings. This was driven by the following questions:

- To what extent can pharmacists undertake the clinical management of patients?

- What extra training is needed to create an ‘advanced’ clinical pharmacist?

- What can a pharmacist uniquely contribute to the joined up, multi-disciplinary, multi-skilled urgent and acute/emergency care workforce of the future?

This work was undertaken through a combination of service improvement studies and a ‘live’ proof-of-concept pilot led by HEE-WM and supported by stakeholders including the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC), the independent regulator for pharmacy in Great Britain; the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), the professional leadership body for pharmacists in Great Britain; the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education (CPPE), a provider of educational solutions for the NHS pharmacy workforce across England; and pharmacist employers.

The following sections go into more detail about this pilot and how these programmes contribute to the understanding and adoption of pharmacist advanced clinical training, with reference to HEE’s plan for pharmacists and their future roles.

West Midlands ED Pharmacy Pilot (PIED-WM)

In December 2013, HEE-WM launched a UK-first pilot study. The methodology followed a dual-site, cross-sectional, observation study of patients attending EDs in the West Midlands[17]

. Three pharmacist prescribers, with support from their ED teams and supervised by an EM consultant, considered a cross-section of ED patient presentations over a five-week period during 2013 ‘winter pressures’ and categorised each according to whether the patient could be managed (see ‘Box 1: Categories in the Pharmacists in Emergency Departments West Midlands [PIED-WM] pilot’).

Box 1: Categories in the Pharmacists in Emergency Departments West Midlands (PIED-WM) pilot

- ‘CP’ Managed by a community pharmacist (avoided emergency department [ED] attendance);

- ‘IP’ Managed by an independent prescriber pharmacist as part of a multi-disciplinary ED team;

- ‘IPT’ Managed by an independent prescriber pharmacist in the ED, with an additional 12 months of clinical skills training, aligned to an “advanced practice” framework (see table 1 – as part of a multi-disciplinary team approach);

- ‘MT’ Managed by the medical team only – unsuitable for pharmacist intervention.

The sample was taken from a cross-section of attendees and care pathways to reflect the usual workload characteristics of the departments. No patient groups were excluded. Primary categorisation of data was undertaken by the onsite project independent pharmacist prescribers. Secondary categorisation was undertaken with reference to the anonymised summary information recorded for this purpose. The data set included age, presenting complaint and clinical grouping. Blind secondary categorisation was undertaken by two community pharmacists and two experienced ED medical consultants. This process was completed personally by each of the secondary categorisers without consultation and without reference to categories assigned by others[17]

.

Outcomes

Primary and secondary categorisation of data was undertaken by the project pharmacist, independent prescribers, their EM consultant supervisors and ED nurse triage teams.

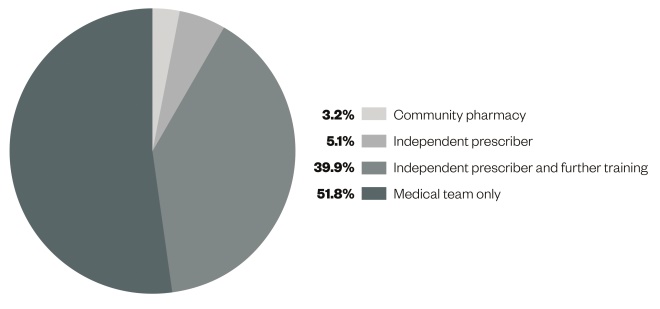

Of the 782 patients surveyed, the study suggested that 48.2% of patients could be managed by a pharmacist, under the overall supervision of a doctor (see ‘Figure 1: Summary outcome data: Pharmacists in Emergency Departments West Midlands [PIED-WM] pilot’)[17]

.

Figure 1: Summary outcome data: West Midlands emergency department pharmacy pilot (PIED-WM)

Each segment represents the percentage of patients surveyed that were suitable to be managed by each category of healthcare professional. The total number of patients surveyed was 782.

Of these patients, it was suggested by the study authors that 39.9% could be managed by a pharmacist with a minimum 12 months’ advanced clinical practice training, aligned to the model in table 1.

| Table 1: Advanced practice framework, used as a guide for the Pharmacists in Emergency Departments West Midlands (PIED-WM) pilot project | |

|---|---|

| Module 1: Clinical examination skills for healthcare professionals (40 CATS points at Masters level) | Module 2: Clinical investigations & diagnostics for healthcare professionals (20 CATS points at Masters level) |

| Aim: To provide the theoretical underpinning and practice base to enable the healthcare professional to deliver safe and effective autonomous care. This will include patients presenting with undifferentiated and undiagnosed primary and secondary care conditions across the age and acuity spectrum | Aim: To complement the clinical examination module to provide the student with the theoretical underpinning for the acquisition of a range of skills and knowledge to support safe autonomous practice when requesting and interpreting clinical investigations for a wide clinical spectrum of conditions |

| Duration: Twelve taught days delivered in six, two-day blocks | Duration: Five taught days delivered via two- and three-day blocks |

Assessment:

Portfolio of evidence from own clinical practice | Assessment:

Portfolio of evidence from own clinical practice |

The pilot was considered a success; fulfilling its primary aims of testing study protocols, forming an initial evidence base and setting guiding principles for further study.

HEE National ED Pharmacy Project (PIED-Eng)

The West Midland’s pilot stimulated interest in a wider study, therefore, HEE commissioned a national project to investigate whether pharmacist prescribers, trained through an advanced clinical practice programme in clinical diagnostics and examination, could positively impact on delivery of patient care in the ED. The PIED-Eng project aimed to build on the West Midlands pilot and, through a similar methodology, aimed to provide evidence to support an enhanced role for pharmacist clinicians in the ED.

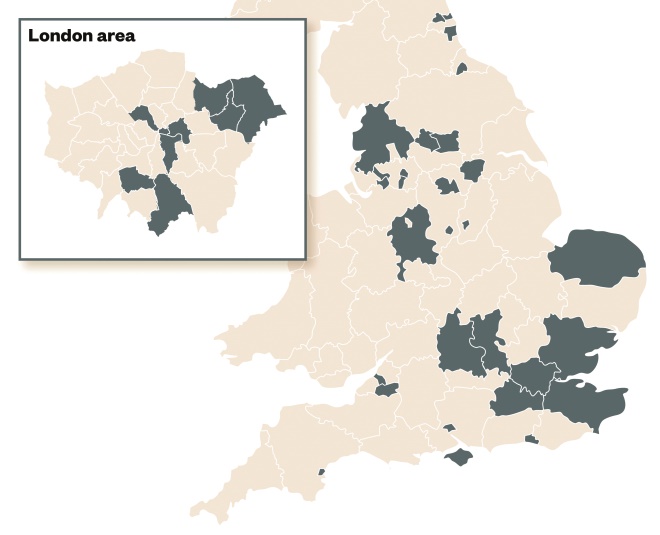

The national study began in March 2015, covering a cross-section of 49 English EDs (Figure 2: Distribution of national PIED project EDs)[19]

. In total, 18,613 sets of patient data were received, making this the largest known study of its kind (to date). Patient presentations were analysed from a cross-section of attendees to reflect a ‘normal’ patient flow through the ED. Pharmacists, with support from their ED teams and each supervised by an EM consultant doctor, categorised patient data as per the groupings described in Box 1. In addition, pharmacists and their supervisors were also asked to describe any specific training needs for each patient presentation.

Figure 2: Distribution of national PIED project EDs

In total, 49 English EDs were included in the project.

Outcomes

In summary, categorisation of 18,613 ED cases evidenced the potential for pharmacists to clinically manage up to 36% of study patients across ‘CP’, ‘IP’ and ‘IPT’ categories. With existing training (i.e. ‘CP’ and ‘IP’ categories) pharmacists could manage 8% of study cases. However, with further training aligned to the advanced clinical practice training pathway, the potential of pharmacists to manage study cases rose by 28% of all cases[18]

. ‘Further training’ for the purposes of this project included a 12-month (postgraduate diploma) advanced clinical practice training course – with modules in clinical examination skills, clinical health assessment and diagnostics. This training programme would be aligned to the advanced clinical practice framework, currently being delivered by HEE, in cooperation with national stakeholders and course providers. Within the ED, the pharmacist typically practised within a multi-professional clinical team, under the overall supervision of a doctor[20]

.

In addition, a secondary categorisation of randomised summary data (a total of 75%, n=13,990) was carried out independently by other (non-site specific) pharmacists, ED consultants and ED nurses. Primary and secondary categorisations were compared and the level of agreement between the two identified. The secondary categorisation of study data supported the validity of the primary categorisation findings, with 36.0–36.7% of study patients being assessed as having potential for clinical management by a pharmacist. The primary and secondary categorisations also demonstrated agreement in the study data between the pharmacists and doctors involved[20]

.

From the study data, clinical groupings where pharmacists were considered to have the highest potential impact were identified as: general medicine, minor trauma, cardiology, general surgery and respiratory. The findings suggested that pharmacists with advanced training (‘IPT’ category) may be most usefully directed to patients in the general medicine and orthopaedic clinical groupings. If training were tailored to concentrate on these two areas, then achievable ‘IPT’ becomes 19%[20]

.

PIED-Eng suggested that a pharmacist prescriber may be utilised in the ED to provide services including:

- Medicines-focused duties in the ED (e.g. pre-discharge medicines optimisation, medicines reconciliation, TTO [’To Take Out’; medicines given to patient on discharge] preparation);

- Undertaking minors-focused (non-major presentations) clinical duties within ED and clinical decision teams;

- Extending urgent and acute service to community and primary care practice.

Such duties are often undertaken unnecessarily by junior medical staff and GPs; roles that face significant demands on their time[21]

. Consideration may be given to such tasks being undertaken by pharmacists, with a consequent workforce impact that may include:

- Faster, safer discharge of patients;

- Improved access to and quality of medicines optimisation in the ED;

- Enhanced ability to contribute to ‘seven-day working’ models;

- Significant contribution to enhancing general practice and community service (e.g. management of long-term conditions as part of a multi-professional team);

- Development of a clinical career framework for pharmacists.

This study supports the view that pharmacist clinicians who follow a clinically enhanced training pathway could competently conduct advanced clinical practice as a ‘specialist generalist’ clinician in urgent, acute and emergency care; working as part of the multi-professional, multi-skilled team, under the supervision of a doctor.

PIED-WM2 and the end of PIED

The final phase of the West Midlands ED Pharmacy pilot launched in June 2016 at the request of HEE and national stakeholders. This final phase – PIED-WM2 – will see the PIED-WM pharmacists returning to the same trust EDs, at the same times of year, following completion of a 12-month advanced practice programme (see table 1). This phase aims to:

- Determine whether, following a structured pathway of clinical skills and diagnostic training – aligned to the advanced practice pathway and of no longer than 12 months duration – the pharmacist practitioner has gained sufficient skills to practice (confidently and competently) at an enhanced clinical level in the ED; managing patients within defined clinical groupings;

- Consider what (if any) additional clinical training – beyond that currently offered within the 12-month advanced practice double module (clinical examination skills and clinical health assessment and diagnostics) – is required to adequately prepare a pharmacist for an enhanced clinical role and further clinical skills development;

- Conclude the evidence base for proposing the training and development of advanced clinical pharmacists in ED, practising as part of a multi-skilled, multi-disciplinary workforce, within a defined range of clinical groupings;

- Evidence the suitability of the advanced practice pathway as a training model for future development of clinical pharmacists.

At the time of writing, the evaluation of PIED-WM2 is eagerly awaited.

What are the next steps?

Clinically Enhanced Independent Prescribing for Pharmacists (CEPIP)

While the PIED study suggested that an advanced clinical training pathway was appropriate for pharmacists, HEE-WM research identified a need for pharmacists to undertake preparatory skills training in clinical health assessment and diagnostics. The programme team investigated whether a clinical skills enhancement to the existing Independent Prescriber (IP) training would satisfy this need. From August 2014, HEE-WM developed and launched a pilot Clinically Enhanced Pharmacist Independent Prescribing programme (CEPIP) – an extension of the existing GPhC-accredited IP programme[22]

. The year-long pilot study tested the following key deliverables:

- Provision of an entry point onto an advanced clinical practice pathway for pharmacists[22]

; - Addition of a targeted clinical skills mix to the existing (GPhC) IP training programme, informed by PIED study data;

- Development of an entry point for a medicines-focused pharmacist clinician training pathway;

- A programme applicable to workforce needs across primary, secondary and community care;

- Accreditation and regulator support for a programme capable of acknowledging accreditation and recognition of prior learning onto regional and national advanced clinical practice programmes.

Box 2: Aims of phase 1

of the Clinically Enhanced Pharmacist Independent Prescribing programme (CEPIP)

- Develop, gain General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) accreditation for, and evaluate a three to four month ‘fast track’ IP module. Recognising that the six-month length of the existing IP programme could not be exceeded, it was considered necessary to condense the IP module, to allow for the addition of clinical skills training;

- Develop and evaluate a suitable range of clinical health assessment and minors training. At this stage, a wide breadth of possible content was considered.

Box 3: Aims of phase 2

of the Clinically Enhanced Pharmacist Independent Prescribing programme (CEPIP)

- Use evaluation data and “lessons learned” from phase 1, to inform a single course brief, set at Level 7 (Master’s level) and awarding a postgraduate Certificate in Independent Prescribing (Pharmacist) (60 Credits – Level 7);

- Engage four West Midlands Pharmacist IP course providers to deliver one CEPIP cohort each.

Collaborative evaluation between the four course providers was expected. This was considered crucial to demonstrate potential for future scale-and-spread.

Phase 1 of the CEPIP pilot launched in August 2014, across three pilot sites – the Universities of Aston, Wolverhampton and Worcester (see box 2). A total cohort of 51 pharmacists from acute and community employers across the West Midlands were recruited. Phase 2 launched in April 2015, across four sites (Aston, Keele, Worcester and Wolverhampton Universities) with a combined cohort of 51 pharmacists from primary, secondary and community practice (see box 3). The pilot concluded in December 2015 [unpublished data][23]

.

During phase 1 and with no basis for comparison, it was considered appropriate to test the baseline course and additional clinical content with acute Trust employers. An exemplar group from a national community pharmacy provider were also added, to test the capability of community pharmacists to undertake the enhanced IP training. Acute employers were known to be well used to IP and advanced practice level training, with designated medical practitioners (DMPs) already engaged in training and a workforce experienced in supporting their practitioners.

Once the course content and brief were confirmed following phase 1 delivery, the phase 2 cohort was opened to recruitment from primary, secondary and community practice.

Figure 3: Collaborative pathway – Clinically Enhanced Pharmacist Independent Prescribing programme (CEPIP) pilot project

The various collaborations between Health Education England – West Midlands (HEE-WM), course providers, employers and pharmacists that were performed during the CEPIP pilot.

From the outset, the collaborative nature of the programme was underlined (see Figure 3). HEE-WM would provide project management and programme oversight, as well as tuition-fee funding and partial backfill support. Course providers were expected to share learning openly – with each other and HEE-WM – and collaborate with the evaluation process[23]

.

Trainees were recruited to the programme on the basis of a signed undertaking to collaborate with the evaluation team during and at zero, six and twelve months post-project. This engagement was considered crucial, both to allow the evaluation team access to workforce data (sufficient to evaluate workforce impact, transformation potential and return on investment) and to underline the fact that inclusion in this programme would not be a ‘line on CV’ exercise for participants. Employers would be expected to demonstrate inclusion of enhanced pharmacist roles in their future workforce planning.

The end result of the pilot and collaborative working between course providers and employers would be:

- The introduction of clinically enhanced pharmacist prescribers to undertake a range of clinical duties in addition to their pharmacist-specific role, against a standardised career development framework and shared competencies;

- Development of a blended, clinically enhanced IP module for pharmacists, capable of being standardised across the region and evaluated with a view to wider scale-and-spread.

Project delivery and outcomes

Pilot cohort practice areas

Table 2 demonstrates the spread of employers from community, secondary and primary care providers. Table 3 shows the breakdown by cohort of practice areas[23]

.

| Table 2: Practice areas and employer organisations – phase 1 and 2 of the Clinically Enhanced Pharmacist Independent Prescribing programme (CEPIP) | |

|---|---|

| Practice areas represented | Employer organisations involved |

| Community practice | 26 |

| Primary care | 5 |

| Secondary (acute) care | 23 |

| Table 3: Phase 1 and 2 cohort dispositions of the Clinically Enhanced Pharmacist Independent Prescribing programme (CEPIP) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Practice area | Pharmacist numbers |

| Phase 1 cohort (51 total) | Community practice | 4 |

| Secondary (acute) care | 47 | |

| Phase 2 cohort (51 total) | Community practice | 22 |

| Primary care | 7 | |

| Secondary (acute) care | 22 | |

Pass and attrition rates: phase 1 and 2 pilot

Phase 1 and 2 course providers confirmed that attrition and pass rates from the pilot courses were comparable to that of their ‘standard’ IP courses (see tables 4 and 5, and additional comments).

| Table 4: Evaluation data – breakdown by course for the phase 1 cohort of the Clinically Enhanced Pharmacist Independent Prescribing programme (CEPIP) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course provider | Cohort size | A ttrition | Pass (1st attempt) | Pass (following resit) | Fail/withdrawal |

| Aston | 23 | 0 | 17 | 4 | 2 |

| Worcester | 11 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| Wolverhampton | 17 | 2 | 13 | 2 | 0 |

| Table 5: Evaluation data – breakdown by course for the phase 2 cohort of the Clinically Enhanced Pharmacist Independent Prescribing programme (CEPIP) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course provider | Cohort size | Attrition | Pass (1st attempt) | Pass (following resit) | Fail/withdrawal | Mitigating circumstances | Comments |

| Aston | 22 | 2 | 10 | 6 | 3 + 1 to resit | x 2 leave of absence – September 2016 return | 3 failed trainees offered restarts (10 distinctions, 5 merits, 1 pass) |

| Worcester | 10 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 1 result pending resubmission outcome | Comparable/better than other IP rates (4 distinctions, 2 merits, 2 passed first attempt) |

| Keele | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | x 2 leave of absence – yet to complete course | – |

| Wolverhampton | 11 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 0 | – | 8 required resits in the OSCE (all 10 passed the portfolio first time and all 10 passed OSCEs after the resit) |

Course director comments: Comparing pass and attrition rates to ‘standard’ IP courses

Additional comments surrounding course progress were noted from course directors, who concluded that the addition of the clinically enhanced component was unlikely to have adversely altered the pattern of results.

Overall, pilot data suggested that pharmacists are capable of completing such training without the risk of “burnout”, or attrition based on an inability to undertake blended clinical and IP training[23]

.

Initial impact assessment

As part of the interim evaluation, the project team conducted interviews with course leads, DMPs, employers and practitioners. Overall, the range of participant responses suggested enhanced workforce capability as a result of exposure to this training, by facilitating clinical areas to reduce winter pressures through prescribing, resolving medication issues and facilitating discharge. Pharmacists could also take histories and perform medicines-focused duties, including medicines optimisation, medicines reconciliation, TTO preparation and minors-focused clinical duties.

Others identified increased patient safety as an impact of the programme. This was attributed to the skills that they acquired on the course, their enhanced pharmacy knowledge and a greater degree of involvement in patient care. Respondents reported that patient experience had been positively impacted through increased communication with patients. Overall, employer and participant perception of the course was positive. Use of study days, support from course leaders / peers and course length were identified as positive features[23]

. Participant comments are included in box 4.

Box 4:

Participant comments

- “I think it’s very much needed. Especially, I think we will be at an advantage compared to all our other colleagues. We will be able to use our skills a lot more.”

- “I work in acute medicine with consultants, with advanced nurse practitioners, with junior doctors and they are very much open arms… can’t wait for me to finish… ‘We can see where you can slot in and be part of the team…’ Essentially on ward rounds and patient assessments on the acute medical unit [AMU].”

- “Constantly you’re hearing about bed management and A&E delays and it makes sense for us to go into acute medicine and help and work with national targets.”

Next steps: 2016 CEPIP delivery – (first non-pilot cohort)

HEE-WM developed and launched their first (non-pilot) clinically enhanced pharmacist independent prescribing (CEPIP) programme in January 2016. The brief was formed from internal (pilot) evaluation outcomes; project team, steering group and stakeholder consultation; and consideration of local and national workforce need and strategic drivers. Courses started in January 2016, across five West Midlands providers, with a combined cohort of 105 pharmacists from primary, secondary and community practice (equally represented). Recruitment demonstrated a high level of interest in the programme from employers, commissioners and the profession itself, across the urgent, acute and EM healthcare economies. A further West Midlands cohort began in September 2016[23]

.

As with the pilot, the 2016 CEPIP programme carries an expectation of collaboration between course providers to deliver a course suitable for standardisation regionally, and for cross-region/national scaling. All course providers delivered programmes according to a single HEE-WM brief.

The HEE-WM project team continues to collaborate and share learning with national stakeholders, including RPS, GPhC and CPPE. HEE-WM and their partners aim to align regional approaches and deliver consistent, clinically enhanced independent prescribing programmes cross-region.

Combined learning to inform future direction

Future direction will include the use of learning from CEPIP, local/national (PIED) ED pharmacy and advanced practice programmes to develop a model competency framework and curricula for advanced clinical pharmacist training (to be prepared as the basis for national stakeholder consultation). This will be accompanied by mapping of required pharmacist competencies against the HEE-led national advanced practice programme to demonstrate the potential (or otherwise) for pharmacists to be a part of future multi-professional advanced practice planning.

Discussion

CEPIP and linked ED pharmacy programmes stand as key examples for innovative workforce development, providing pharmacists with a wide-range of skills to improve the quality and efficiency of healthcare delivery within urgent and acute settings. The project team proposes such a programme will contribute to higher productivity and support the seven-day working model[23]

.

It is a reality of today’s UK healthcare economy that gaps are appearing in the clinical workforce on an ever-wider scale. Medical recruitment – especially in EM and general practice – is simply not training or recruiting sufficient doctors to support the needs of an increasingly ageing population, presenting with ever more complex health needs[24]

. Furthermore, while it is right to enhance skills training for nursing and allied health professions, it would be counterproductive and short-sighted to overlook other professions in favour of ‘stripping’ or over-stretching existing clinical roles, to meet demand in other areas.

In its 2014 report, the NHS Urgent Care Commission recommended that “…a multi-disciplinary approach must be taken to staffing urgent care services. The spectrum of advanced practitioners available to deliver services should be expanded to include pharmacists; nurses; physician associates; and healthcare assistants”[25]

. The HEE-WM pharmacy transformation programme supports and follows government policy, relating to the development of multi-specialty community providers and the integrated, multi-professional, front-line clinical workforce.

The ‘NHS England five year forward view’ states “in order to achieve an understanding of how different healthcare services can work collectively, new models of training are needed to prepare healthcare professionals for a career in a more joined-up workforce, with the knowledge and skills that span the management of acute health needs across community and secondary care environments[4]

”.

The programme team proposes that enhancing pharmacists’ clinical training will demonstrate benefits across community, primary and secondary care[23]

.

The PIED-ENG programme continues to create an impact, with acute trusts nationally requesting the PIED-ENG data to support local workforce development. For example, East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust confirmed, following its involvement in the study, that a pharmacist will now be permanently based in the ED at Royal Blackburn Hospital, in an attempt to address local workforce challenges. Neil Fletcher, clinical director of pharmacy at East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust, reported that: “We are pleased with how the pilot went here and are very keen to take this work forward. We are now looking at putting a pharmacist in the emergency department, who can be part of the team there and support with the triaging of patients”.

Sir Bruce Keogh, NHS England medical director, confirmed that key outcomes from the ED pharmacy project work would include “…a positive impact on patient safety, improved patient experience and throughput, expediting safe discharge of patients from hospital and, consequently, an increased capacity in the acute-care pathway[26]

.”

David Branford, RPS English Pharmacy Board chair, endorsed the ED pharmacy project work on behalf of RPS: “The RPS believes that pharmacists could make a significant impact on patient care by adding both capacity and capability to emergency departments. Hospital pharmacy has been at the forefront of advanced clinical practice for some time and I have no doubt chief pharmacists and their teams will respond positively to this opportunity. We are fully supportive of the work being undertaken by HEE to further evidence the value of pharmacists within emergency departments.”

The evaluation undertaken during the PIED study has extensively examined the potential future role of pharmacists, beyond their usual current scope of practice of medicines management and optimisation. This is the first study that has examined the potential advanced clinical role of pharmacists managing cases in the ED, and hence there is no comparable study nationally or internationally to critique. Other published studies that have examined traditional pharmaceutical care type roles for emergency pharmacists have measured the proportion of time that pharmacists have spent on certain activities – such as medicines reconciliation and dose adjustment, but have not evaluated whether pharmacists need additional training – as these skills are already present and transferable from their education and training[13],[14],[15],[16]

.

Given the workforce challenges, evidence from PIED that underpins advanced clinical skills training for pharmacists, and expectations of adoption across the country, can the current ‘traditional’ clinical diploma be replaced by the new advanced ‘hands-on-patients’ training?

The argument then is this: unless we use our existing workforce more intelligently and support the development of new roles from sustainable sources, gaps will remain and, indeed, will continue to grow exponentially; proportionate to increasing patient demand.

Conclusion

With a stable and sustainable workforce comes an increased ability for employers to quality assure clinical standards, reduce reliance on locums (particularly important in light of the recent government decision to cap locum spending) and deliver safe, effective and ‘joined-up’ patient care.

It is proposed that a fundamental part of any future primary and secondary care workforce planning should include an understanding of emerging professions and the benefits of recruiting complementary medical and non-medical roles in the future, ‘joined-up’, urgent, acute and EM workforce.

The project team is confident in proposing enhanced clinical development pathways for pharmacists, as the basis for a change in thinking around the future integrated clinical workforce across urgent, acute and emergency care.

Author disclosure and conflicts of interest

The PIED studies and CEPIP courses were commissioned by Health Education England.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts. Emergency admissions to hospital. [online] 2014. Available at: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmpubacc/885/885.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[2] Care Quality Commission. The state of healthcare and adult social care in England 2013/14. [online] 2014. Available at: http://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/state-of-care-201314-full-report-1.1.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[3] Aldicott R. The King’s Fund. Workforce planning in the NHS. [online] 2015. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/Workforce-planning-NHS-Kings-Fund-Apr-15.pdf (accessed Janaury 2017)

[4] NHS England. Five year forward view. [online] 2014. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[5] The King’s Fund. Workforce planning in the NHS. [online] 2015. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/Workforce-planning-NHS-Kings-Fund-Apr-15.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[6] Henderson KI, Gotel U & Hill J. Using a clinical pharmacist in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2015;32:998–999. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-205372.45

[7] Guardian newspaper. Can involving pharmacists in A&E shorten waiting times and help doctors? [online] 2015. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2015/sep/09/pharmacists-shorten-waiting-times-help-doctors (accessed February 2017)

[8] LinkedIn Jobs. Lead pharmacist for the emergency department/ [online] 2015. Available at: https://uk.linkedin.com/jobs/view/157774725 (accessed February 2017)

[9] Ahmed S, Collignon U & Oborne CA. The application of explicit criteria to identify accident and emergency patients suitable for management solely by a pharmacist. Pharm J 2007;279:73–76. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/10967868.article

[10] Collignon U, Oborne A & Kostrzewski A. Pharmacy services to UK emergency departments: a descriptive study. Pharm World Sci 2010;32:90–96. doi: 10.1007/s11096-009-9347-3

[11] Fairbanks RJ, Rueckmann EA, Kolstee KE et al. Clinical Pharmacists in Emergency Medicine. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, et al., editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 4: Technology and Medication Safety). Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008 Aug. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43767/ (accessed February 2017)

[12] Policy statements. Clinical pharmacist services in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:444–445. Available at: https://www.acep.org/clinical—practice-management/clinical-pharmacist-services-in-the-emergency-department (accessed 30 January 2017)

[13] Matthies G. Practice spotlight. Emergency department pharmacist who makes house calls. Can J Hos Pharm. 2012;65:147. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v65i2.1121

[14] Henriksen JP, Noerregaard S, Buck TC & Aagaard L. Medication histories by pharmacy technicians and physicians in an emergency department. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(6):1121–1127. doi: 10.1007/s11096-015-0172-6

[15] Proper S, Wong A, Plath E et al. Impact of clinical pharmacists in the emergency department of an Australian public hospital: a before and after study. Emerg Med Australasia. 2015;27(3):232–238. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12384

[16] Abdelaziz H, Al AR, Elmalik A et al. Impact of clinical pharmacy services in a short stay unit of a hospital emergency department in Qatar. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(4):776–779. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0290-9

[17] Hughes E, Aiello M & Terry D. Clinical pharmacists in urgent and acute care – the future pharmacist. Commissioning [online] 2014;1:48–53. Available at: http://commissioningjournal.com/downloads/Commissioning-1-6-share.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[18] Nuffield Trust. Expanding skills of existing staff, best way to develop NHS workforce for 21st century. [online] 2016. Available at: http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/node/4652 (accessed February 2017)

[19] Health Education England. Executive Summary: pharmacist development in emergency medicine. [online] 2015. Available at: https://hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/PIED%20National%20Report.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[20] Terry D, Petridis K, Aiello M et al. The potential for pharmacists to manage patients attending emergency departments. Int J Pharm Pract. 2016;24 (Suppl1)(4).

[21] Open forum events. Improving urgent and emergency care through better use of pharmacists. [online] 2015. Available at: http://www.openforumevents.co.uk/improving-urgent-and-emergency-care-through-better-use-of-pharmacists/ (accessed February 2017)

[22] Health Education England. Advanced clinical practice framework for the West Midlands. [online] 2015. Available at: https://hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/ACP%20Framework%20for%20the%20WM.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[23] NHS Health Education England (2014–16). Clinically Enhanced Pharmacist Independent Prescribing Programme. Data on file. [Unpublished data]. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/08/clin-pharm-gp-pilot-faqs-0815.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[24] NHS England: Transforming urgent and emergency care services in England. Urgent and Emergency Care Review End of Phase 1 Report: Appendix 1 – Revised Evidence Base from the Urgent and Emergency Care Review. [online] 2013. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/keogh-review/Documents/UECR.Ph1Report.Appendix%201.EvBase.FV.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[25] Urgent Care Commission. Urgent and important: the future for urgent care in a 24/7 NHS. [online] 2014. Available at: http://www.careuk.com/sites/default/files/Care_UK_Urgent_and_important_the_future_for_urgent_care_in_a_24_7_NHS.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[26] NHS England (2014). Urgent and Emergency Care Review: Progress and Implementation Plan (online). Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/item8-board-1214.pdf (accessed February 2017)