Steve Gschmeissner / Science Photo Library

In this article you will learn:

- How to recognise the clinical features of urinary tract infection, including typical and atypical symptoms

- The antimicrobials available for treatment and their optimisation in elderly patients

- How to assess patients with recurrent urinary tract infections to determine the appropriate treatment strategy

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common reasons for using antibiotics in both primary and secondary care[1]

. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that UTI accounts for 1–3% of all GP consultations per year[2]

. Data from NHS England (2012–2013) shows that UTI was one of the most frequent reasons for emergency hospital admissions, with 67 admissions per 100,000 population, per quarter, on average[3]

. UTIs are the second-largest single group of healthcare-associated infections in the UK, accounting for 19.7% of all hospital acquired infections[4]

.

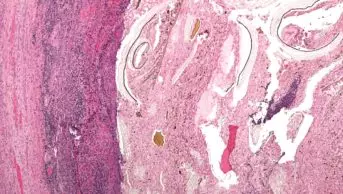

UTIs can be classified as ‘uncomplicated’ (sometimes referred to as a ‘simple’ UTI) or ‘complicated.’ Uncomplicated infections present most frequently in women without any structural or functional abnormality of the urinary tract, any history of renal disease, or other comorbidity (e.g. immunocompromised patients or those with diabetes), which may contribute to more serious outcomes. Complicated UTIs are associated with a condition or underlying disease that interferes with the patient’s immune mechanisms and increases the risk of acquiring infection. UTIs in men are generally regarded as complicated infections.

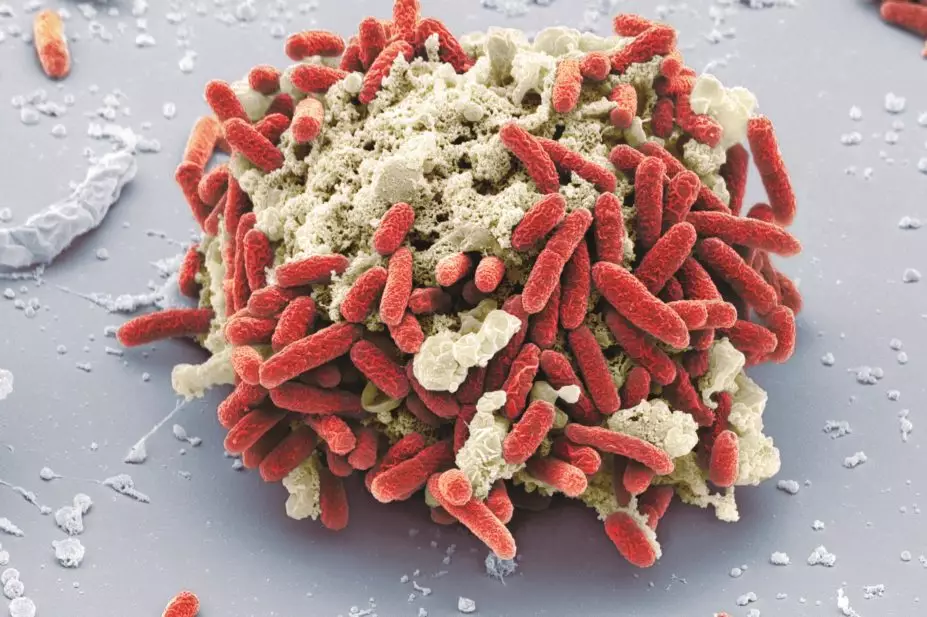

Escherichia coli is still the most common causative organism. However, in patients with catheters or residents of care homes, a broader range of Gram-negative bacilli, including Proteus, Klebsiella and Pseudomonas spp. are also frequently cited as causative organisms[5]

.

Incidence of UTIs and the risk of developing a UTI increases significantly with age in both men and women. The annual incidence of UTIs in the general elderly population has been estimated at approximately 10%, rising to 30% for residents of care homes or other care institutions[5]

. The increase in incidence is caused by a range of factors seen in older people, including higher intravaginal pH in postmenopausal women, increased residual volume in the bladder and a weakened immune system.

Around 43–56% of all UTIs are associated with use of a catheter. It is currently estimated that approximately 15–25% of hospitalised inpatients and 10% of residents in care homes have a long

term catheter in situ. Bacteriuria occurs in around 30% of catheterised patients anywhere between two and ten days after catheter insertion, with a further 24% of these patients developing symptoms of a catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI). Around 4% of these CAUTIs will further develop into life threatening conditions, such as bacteraemia (the presence of bacteria in the blood) or sepsis, with mortality rates ranging up to 33%[6]

.

Clinical features

Presentation of UTIs can vary and range from patients exhibiting with limited clinical symptoms to urinary sepsis. Infection of the urinary tract can affect both the lower and upper parts of the urinary tract. Lower UTI can be defined as evidence of UTI with symptoms suggestive of cystitis (dysuria, or increased urinary frequency without fever, chills or back pain), while upper UTI can present with symptoms suggestive of pyelonephritis (loin pain, flank tenderness, fever, rigors, or other manifestations of systemic inflammatory response)[1]

. Urosepsis may be diagnosed when clinical symptoms of infection are accompanied by signs of systemic inflammation (e.g. fever, tachycardia, tachypnoea)[7]

.

Catheterised patients do not always present with typical clinical symptoms of a urine infection. Elderly patients with UTIs commonly present with non-specific or atypical symptoms, which can lead to a delay in accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment. For more information on the differentiation between typical and atypical symptoms, see ‘Typical and atypical symptoms of UTI’.

Diagnosis

In elderly patients, diagnosis of UTIs should always be based on a full clinical assessment, including observation of vital signs. If a patient has any symptoms or signs of non-urinary infection, then this should be managed accordingly.

A sample of urine should be obtained from the patient and sent to a microbiology lab. This sample will be cultured to detect bacterial growth in the urine, which can be indicative of infection and can guide antibiotic therapy. Guidance from Public Health England (PHE) states that urine should only be sent for culture if the patient has two or more signs of infection (especially dysuria, fever, or new incontinence)[8],[9]

. Older patients are more likely to have asymptomatic bacteriuria, defined as the presence of bacteria in urine without any symptoms of infection of the urinary tract.

Urinalysis and urine culture can be used to diagnose acute pyelonephritis. The consensus definition of pyelonephritis, established by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), is a urine culture showing at least 10,000 colony-forming units per mm3 and symptoms compatible with the diagnosis. In patients with a history of fever or back pain, the possibility of an upper UTI should be considered[10]

.

Urine dipstick testing for nitrites of leucocyte esterase is of limited value for diagnosis of a UTI in otherwise healthy women aged under 65 years, who present with mild, or two or fewer, symptoms of a UTI (see ‘Typical and atypical symptoms of UTI’). Urine dipstick testing is of no value in diagnosing UTIs in catheterised patients and there is no robust evidence to support the use of urine dipstick testing in patients aged over 65 years[1]

.

| Typical and atypical symptoms of UTI | |

|---|---|

| Typical symptoms of UTI | Atypical symptoms of UTI |

| Fever | Altered mental state |

| Dysuria | New-onset incontinence |

| Loin pain | Nausea and vomiting |

| Increased urinary frequency | Urinary retention |

| Haematuria | Abdominal pain |

| Flank or suprapubic pain | Worsening in diabetes control |

| Rigors |

Treatment

UTI treatment should always be in line with local guidelines or based on microbiology results. Treatment options may include antimicrobials, including amoxicillin, cefalexin, ciprofloxacin, co-amoxiclav, pivmecillinam and fosfomycin.

Optimisation of antimicrobials for UTI in elderly patients

- Do not start antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in the elderly or in catheterised patients;

- Always send a sample for culture before starting antibiotic therapy;

- Check previous culture and sensitivity results before prescribing;

- Use local guidelines when deciding which antibiotic to give;

- Ensure the correct course length is prescribed (i.e. seven days for a man, or minimum of seven days for a CAUTI);

- Ensure the patient completes the full course (even if symptoms improve).

The Sco

ttish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN Guidelines No. 88) recommend the use of a three-day course of trimethoprim tablets 200mg twice a day, or nitrofurantoin modified release capsules 100mg twice a day for non-pregnant women of any age, who have signs or symptoms of an acute lower UTI. Guidance from PHE suggests that a seven-day course of nitrofurantoin (modified release 100mg twice a day) may be considered for men with symptoms of uncomplicated lower UTI, where pre-treatment midstream urine has been sent for analysis and the possibility of pro

statitis has been considered

[11]

. Care

should be taken when prescribing nitrofurantoin for elderly patients, who may be at increased risk of pulmonary, hepatic, neurological, blood disorders (such as agranulocytosis and thrombocytopenia) and gastrointestinal side effects (such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea). Nitrofurantoin is contraindicated in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 45ml/min/1.73m

2, which in effect means it is contraindicated in a large proportion of the elderly population because of age-related decline in renal function. Guidance issued from the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency states that a short course (three to seven days) may be used in patients with an eGFR of 30–44ml/min/1.73m

2, but only to treat lower UTI with suspected or proven multidrug resistant pathogens, when the benefits of nitrofurantoin are considered to outweigh the ris

k of side effects

[12]

. In

addition, it is recommended that renal function should be monitored when using nitrofurantoin in elderly patie

nts

[13]

.

Once the patient has been assessed to determine whether urinary retention is likely, treatment with antibiotics should be started following local policies, or based on results from microbiology tests. If the patient has an indwelling catheter, this should be removed and replaced, and the ongoing need for catheterisation should be reviewed.

Analgesia should be offered for treatment of any pain, with choice of therapy dependent on the patient’s other comorbidities. A mild analgesic such as paracetamol is usually appropriate. Patients with fever and chills, or new-onset hypotension, should be referred and may need to be admitted to hospital.

A Cochrane review has showed no clinical benefit of treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in patients who are not pregnant[14]

. Antibiotics should therefore never be initiated in asymptomatic elderly patients.

For treatment of acute pyelonephritis, PHE recommend empirical treatment with ciprofloxacin 500mg twice daily or co-amoxiclav 500/125mg three times a day, for a minimum of seven days. If a patient is at risk of infection from an extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing organism, advice regarding treatment should be sought from a microbiologist. Upper UTI can be accompanied by bacteraemia, making it a life threatening infection. If the patient does not respond to antibiotics within 24 hours, they must be admitted to hospital because of the possibility of antibiotic resistance.

Recurrent UTI

Cases of recurrent UTI (defined as three or more separate episodes in one year[15]

) can be managed in a number of ways. All risk factors in elderly patients should be mitigated where possible (e.g. treatment of atrophic vaginitis with topical oestrogens, trial of removal of unnecessary indwelling catheter) and all patients should be advised to maintain adequate fluid intake – a conservative estimate for older adults is that daily intake of fluids should not be less than 1.6 litres per day[16]

to prevent further infection. Patients presenting with recurrent UTI with no obvious risk factors should be referred to a urologist.

Daily antimicrobial prophylaxis has been found to reduce the recurrence of UTI in women[17]

. However, the supporting evidence for use of daily antibiotics is of low quality — the most recent clinical trial was conducted in 1997 and did not examine the effects of prophylaxis beyond 12 months. Furthermore, there is no clear evidence on the optimal duration of prophylaxis or optimum doses of antibacterials to use. Most evidence-based trials have used microbiological recurrences as the main outcome, rather than focusing on clinical outcomes[18]

. There is not an ideal prophylactic agent, as all antibiotics are associated with problems of increasing resistance and occurrence of adverse effects, including rashes and gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim are the ‘usual’ first line prophylactic therapies, but prophylaxis should always be based on local guidelines, recent urine culture and sensitivity results.

Prior to commencing a prophylactic agent, patients or their representatives should be counselled at an early stage to inform them that antibiotic prophylaxis is not usually a life-long treatment. Patients should be informed that they are being given antibiotic prophylaxis daily for a period of time to allow the bladder to heal and reduce the likelihood of a UTI. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be given for a maximum of six months and prescriptions should have a review date documented in the medical notes and/or on the prescription. If a patient contracts a lower UTI during this six month period, a urine sample should be sent for culture and sensitivity testing. The UTI should be treated with a three-day course of a suitable antibiotic based on the urine culture results and the prophylaxis resumed, switching to a different antibiotic where appropriate. After the six-month period, prophylaxis should be stopped. If prophylaxis is continued (e.g. if there is no identifiable causes of recurrent UTI, and withdrawal of prophylaxis has led to recurrence of infection), it should be reviewed periodically (ongoing need should be discussed at least on an annual basis), with a view to cessation.

Daily antimicrobial prophylaxis is not recommended in men, or any patient with an indwelling catheter, except on the advice of a specialist urologist, nephrologist or microbiologist[17]

.

Benjamin Kelly-Fatemi MRPharmS

is a Care Homes Medicines Optimisation Pharmacist, NHS North of England Commissioning Support.

References

[1] Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults Edinburgh: SIGN; 2012. (SIGN Guideline no. 88). Available at: http://www.sign.ac.uk (accessed June 2015).

[2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Urinary tract infection (lower) — women. London: NICE 2014. Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/urinary-tract-infection-lower-women#!topicsummary (accessed June 2015).

[3] NHS England. Emergency admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions — characteristics and trends at national level. March 2014. Available at: http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/red-acsc-em-admissions-2.pdf (accessed June 2015).

[4] Department of Health. Saving lives high impact intervention No 6. Urinary catheter care bundle. 2007. Available at: http://tinyurl.com/37qgzbp (accessed June 2015).

[5] Cove-Smith A & Almond MK. Management of urinary tract infections in the elderly. Trends U rol Gynaecol Sex Health 2007;12:31–34.

[6] Loveday HP, Wilson JA, Pratt RJ et al. Epic 3: National evidence based guidelines for preventing healthcare associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. Journal of Hospital Infection 2014;86(1):S1–70.

[7] Om Prakash K & Alpana R. Approach to a Patient with Urosepsis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2009;1(1):57–63.

[8] Little P, Turner S, Rumsby K et al. Dipsticks and diagnostic algorithms in urinary tract infection: development and validation, randomised trial, economic analysis, observational cohort and qualitative study. Health Technology Assessment 2009;13(19):1–96.

[9] Bent S, Nallamothu BK, Simel DL et al. Does this woman have an acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection? JAMA 2002;297:2701–2710.

[10] Rubin RH, Shapiro ED, Andriole VT et al. Evaluation of new anti-infective drugs for the treatment of urinary tract infection. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Food and Drug Administration. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15(1):S216–227.

[11] Department of Health, Public Health England. Managing common infections: guidance for consultation and adaptation (accessed April 2015).

[12] Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Drug safety Update. 25 September 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/nitrofurantoin-now-contraindicated-in-most-patients-with-an-estimated-glomerular-filtration-rate-egfr-of-less-than-45-ml-min-1-73m2 (accessed June 2015).

[13] Medicines Health and Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Drug Safety Update. Nitrofurantoin now contraindicated in most patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 45 ml/min/1.73m2. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/nitrofurantoin-now-contraindicated-in-most-patients-with-an-estimated-glomerular-filtration-rate-egfr-of-less-than-45-ml-min-1-73m2 (accessed June 2015).

[14] Cochrane Review. Asymptomatic bacteriuria. 2015.

[15] Epp A, Larochelle A, Lovatsis D et al. Recurrent urinary tract infection. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32:1082–101.

[16] Institute of Medicine (US). Panel on Dietary References Intakes for Electrolytes and Water. Dietary references intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride and sulphate. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2004.

[17] Scottish Medicines Consortium. Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group. Guidance to improve the management of recurrent lower urinary tract infection in non-pregnant women. January 2014.

[18] Antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in non-pregnant women (Review). The Cochrane Library 2008, Issue 4.