Science Photo Library

Oral dryness (xerostomia) is a common condition in the adult population, affecting around 27% of females and 21% of males; but its overall prevalence increases to 39% in people aged over 65 years[1]

.

Xerostomia can be subjective, especially when patients feel that their mouth is dry, but clinical examination does not reveal any abnormality or cause. This so-called ‘subjective oral dryness’ can be related to transient causes, including dehydration and anxiety. However, a long-term sustained feeling of oral dryness for more than three months is indicative of reduced production of saliva (hyposalivation) and is termed objective oral dryness[1]

. This is usually the result of salivary gland hypofunction, resulting in a significant reduction of unstimulated and/or stimulated salivary flow[2]

.

This article describes the physiology and functions of saliva, and provides a summary of the signs, symptoms, aetiology and management of dry mouth, including the use of salivary stimulants and substitutes, together with guidance on when and to whom to refer patients with xerostomia.

Physiology of saliva

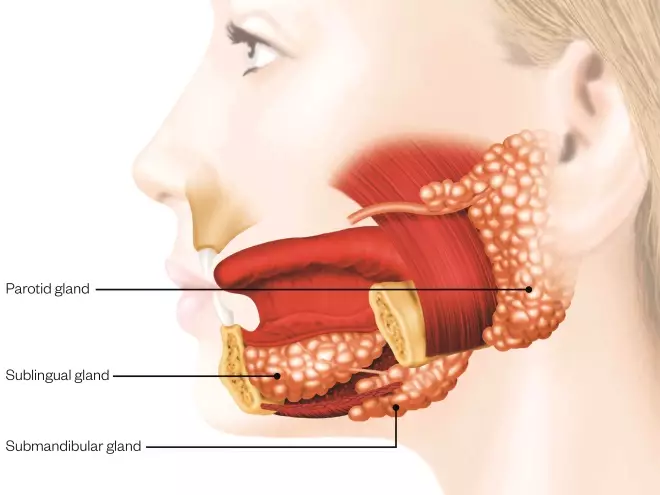

Saliva is produced by both major and minor salivary glands. There are three pairs of major salivary glands: the parotid, submandibular and sublingual glands[3]

. The parotid is the largest salivary gland, located in the pre-auricular area (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Salivary glands

Source: Science Photo Library

Humans have three paired major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands.

Parotid gland: The two parotid glands are major salivary glands wrapped around the mandibular ramus. The largest of the salivary glands, they secrete saliva to facilitate mastication and swallowing, and amylase to begin the digestion of starches. It is the serous type of gland that secretes ptyalin. It enters the oral cavity via the parotid duct (Stensen duct).

Submandibular gland: The submandibular glands are a pair of major salivary glands located beneath the lower jaws, superior to the digastric muscles. The secretion produced is a mixture of both serous fluid and mucus, and enters the oral cavity via the submandibular duct or Wharton duct. Around 65–70% of saliva in the oral cavity is produced by the submandibular glands.

Sublingual gland: The sublingual glands are a pair of major salivary glands located inferior to the tongue, anterior to the submandibular glands. The secretion produced is mainly mucous in nature; however, it is categorised as a mixed gland. The ductal system of the sublingual glands does not have intercalated ducts and usually does not have striated ducts either, so saliva exits directly from 8 to 20 excretory ducts known as the Rivinus ducts. Around 5% of saliva entering the oral cavity comes from these glands.

The saliva produced by this gland is mainly serous (watery) saliva secreted through an opening in the buccal mucosa. The submandibular and sublingual glands lie in the submandibular space under the tongue and produce mainly mucous saliva, which puddles in the floor of the mouth[3]

(see Figure 1).

There are around 800 minor salivary glands located throughout the mouth, located in the labial mucosa, buccal mucosa, the lateral borders of the tongue, retromolar pad and glossopharyngeal area. These glands secrete mucous saliva directly onto the oral mucosa[4]

.

It is estimated that healthy individuals produce around 0.75–1.5l of saliva per day, 70% of which is secreted by the submandibular glands and around 20% by the parotid glands (only small amounts are secreted from the other salivary glands). Although large volumes of saliva are produced during the course of a single day, salivary flow reduces to near zero during sleep[5]

.

Composition

Saliva comprises at least 99% water and a complex mixture of proteins, enzymes, inorganic ions, antibacterial agents and amino acids[5]

. The production of saliva is stimulated both by the sympathetic nervous system (viscous saliva) and the parasympathetic (watery saliva). Parasympathetic stimulation leads to acetylcholine (ACh) release onto the cells in the salivary glands that bind to muscarinic receptors leading to secretion[6]

. ACh also causes the salivary glands to release kallikrein, generating vasodilation and increased blood flow, allowing the production of more saliva. Both parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous stimulation play a role in releasing secretions from the secretory acinus into the salivary ducts and eventually to the oral cavity[6]

. Saliva production can be pharmacologically enhanced by sialagogues (e.g. pilocarpine) and suppressed by antisialagogues (e.g. atropine)[7]

.

Function of saliva

Saliva is essential for the following functions:

- Lubrication, aiding chewing and swallowing of food;

- Digestion of starch and fat. The salivary enzyme amylase (ptyalin) breaks down starch into simpler sugars. Saliva also contains lipase, which helps the fat-digestion process — especially in neonates, as their pancreatic lipase is still not fully developed;

- Providing a sense of taste by dissolving chemicals in the food and carrying it to taste receptors;

- Aiding pronunciation;

- Providing antibacterial action;

- Buffering to maintain neutral pH;

- Lavage — the absence of normal salivary flow and lack of lavage encourages dental plaque stagnation, leading to increased rates of caries and periodontal (gum) disease;

- Protecting and promoting healing of mucosal oral and gastroesophageal tissues.

Signs and symptoms of dry mouth

People experiencing xerostomia may present with a range of signs and symptoms. For example, the dorsum of the tongue may become depapillated (see Figure 2, Panel 1) or fissured and coated (see Figure 2, Panel 2). They may have the appearance of a dry shiny mucosa or an absence of a saliva pool on the floor of the mouth (see Figure 2, Panel 3), loss of stippling of the gingiva, stained teeth (see Figure 2, Panel 4) and multiple dental restoration (see Figure 2, Panel 5).

Figure 2: Signs and symptoms of xerostomia

Source: Courtesy, Anwar R Tappuni

1. Depapillated tongue: Soreness of the tongue, or more usually inflammation with depapillation of the dorsal surface of the tongue (loss of the lingual papillae), smooth and erythematous (reddened) surface

2. Fissured/coated tongue: Cracks, grooves or clefts appear on the top and sides of the tongue. Fissures may vary in depth (up to 6mm) and may connect with other grooves, separating the tongue into small lobes or sections

3. Absence of saliva on mouth floor: Gives appearance of a dry shiny mucosa, with no characteristic saliva pool on the floor of the mouth

4. Loss of stippling of the gingiva: Characteristic ’orange peel’ appearance lost. Stippling is a consequence of the microscopic elevations and depressions of the surface of the gingival tissue due to the connective tissue projections within the tissue

5. Multiple dental restoration: When present, in addition to any of the signs and symptoms above, this can indicate that the person is living with xerostomia

Additional symptoms that patients may present with are included in Box 1.

Box 1: Common symptoms of dry mouth that patients may present with

- Burning sensation or oral soreness;

- An increased rate of dental disease, including caries and tooth wear;

- Plaque and debris retention in the mouth, leading to poor oral hygiene and halitosis;

- An increased susceptibility to periodontal disease and tooth loss;

- Difficulty retaining dentures in the mouth;

- Recurrent infections of the major salivary glands, especially parotitis;

- An increased risk of recurrent oral infections especially oral candidiasis and angular cheilitis;

- Taste impairment or dysgeusia (i.e. disordered taste, such as a reduced ability to taste or having a bad, metallic taste at all times);

- Speech impediment;

- Difficulty in chewing and swallowing, which can lead to undernourishment;

- Dry cough;

- Hoarse voice.

Xerostomia is diagnosed according to signs and symptoms of oral dryness rather than by any quantitative or qualitative analyses of saliva. The condition may be exacerbated by mouth breathing, which is often associated with nasal obstruction.

Aetiology of oral dryness

There are a wide range of potential causes of xerostomia[8]

, including:

- Side effects of drugs — at least 400 kinds of medications have been reported to cause dry mouth. Salivary flow is particularly reduced when two or more hyposalivatory drugs are taken simultaneously and for long periods[9]

. Examples of xerogenic medications include:- Cardiovascular agents, including antihypertensive drugs;

- Antidepressants;

- Tranquilisers and hypnotics;

- Antipsychotic agents;

- Amphetamine derivatives;

- Anticonvulsants;

- Antiparkinsonian drugs;

- Some gastro-intestinal and genitourinary systems agents;

- Respiratory system and anti-allergic agents, including antihistamines;

- Some steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs;

- Antineoplastic agents.

- Lifestyle

— athletes and smokers are more prone to dehydration and oral dryness; - Habits— mouth-breathing and low water intake;

- Salivary gland conditions

— such as tumours; - Systemic diseases affecting exocrine glands — such as Sjögren’s syndrome, a long-term autoimmune disease where the moisture-producing glands of the body are affected, resulting primarily in the development of a dry mouth and dry eyes. Other systemic diseases that can cause xerostomia include diabetes, liver disease, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, thyroid disease and HIV-related salivary gland disease;

- Cancer treatment— patients undergoing chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, especially of the head and neck;

- Neurological conditions — such as Alzheimer’s or stroke, which may cause change in oral perception due to nerve damage.

Management of oral dryness

The British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) set up a Guideline and Audit Working Group in 2015 to produce national guidelines for the management of adults with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. These guidelines were published in June 2017, and included a comprehensive section on the management of oral dryness in these patients[10]

. A synopsis of the mouth management guidelines for Sjogren’s syndrome patients is as follows:

Recommendations for oral health in dentate patients

- Dry mouth patients, who may report an improvement in symptoms with room air humidification only[10]

, should be advised to practise excellent oral hygiene. The advice should include brushing their teeth at least twice daily (but not immediately after eating), including last thing at night, using a pea-sized amount of high-fluoride content toothpaste. Dry mouth patients need to use a high-fluoride content toothpaste to compensate for the lack of salivary fluoride. Concentrations of fluoride in ‘standard’ over-the-counter (OTC) toothpastes vary from 500 parts per million (ppm) to 1,000ppm and occasionally higher. ‘Prescription’ toothpastes contain fluoride concentrations of between 2,800ppm and 5,000 ppm. A number of studies[11],[12],[13]

and a Cochrane review[14]

have concluded that protection from caries is increased with the use of higher fluoride concentration toothpastes. This protection may be enhanced by the use of fluoride-containing tooth mousse or gels, applied twice daily between brushing. Dry mouth patients should avoid the use of alcohol-containing mouth washes, the consumption of fizzy drinks (especially sugar-containing fizzy drinks), and frequent snacking[15]

; - Patients diagnosed with dry mouth require regular dental recall appointments, possibly only a few months apart, and a prevention regime that may include high-concentration fluoride mouthwash in addition to high-fluoride content toothpaste, gels and tooth mousses;

- Dietary advice for dry mouth patients should emphasise the avoidance of dietary sugars, especially sugar-containing snacks, to counteract the risk of developing caries and the need to limit the consumption of acidic foods and drinks. Acidic products and those containing sugar should not be prescribed for dentate patients. Dry mouth patients may elect to avoid highly spiced foods;

- Chlorhexidine mouthwash can be an effective antiseptic and useful for controlling gingivitis[16]

. Many recommend an alcohol-free chlorhexidine mouthwash for use by dry mouth patients to help prevent periodontal disease. This can be used twice daily for a maximum of two weeks every three months, but overuse can lead to, among other adverse side effects, staining of teeth and oral soreness.

Recommendation for oral health in edentulous patients

Oral health in edentulous dry mouth patients may be improved and maintained by:

- Meticulous denture hygiene[17]

; - Rinsing dentures and the mouth on a number of occasions throughout the day, especially after meals;

- Leaving dentures out for at least part of the day, preferably overnight.

Saliva substitutes

The premise of treating oral dryness is to conserve, stimulate and replace saliva. If the symptoms of dry mouth are mild, sipping water or chewing sugar-free gum may be enough to relieve the discomfort[15],[18]

.

Moderate-to-severe dryness is usually managed with commercially available topical saliva substitutes. Saliva substitutes are in the form of oral sprays, gels and rinses. Most are available over the counter, although some are prescription-only. Fluoride-containing, neutral pH preparations should be prescribed for dentate patients. Preparations with acidic pH and/or without added fluoride should only be used in edentulous patients. A Cochrane review of the effectiveness of topical treatments for dry mouth did not find strong evidence for the effectiveness of lozenges, sprays, mouth rinses, gels, oils, chewing gum and toothpastes[19],[20]

. However, patients report increased oral comfort with the use of one or more of these products[15]

.

Topical saliva stimulants

Sugar-free gum is also recommended for the management of dry mouth. The mechanical action of chewing stimulates saliva production. Additionally, there is some evidence that the non-sugar sweetener xylitol may have a role in caries prevention in its own right[21],[22],[23]

. A number of salivary stimulants are commercially available in the UK; however, there is little convincing evidence of their efficacy[24],[25]

.

Systemic saliva stimulants

Pilocarpine hydrochloride acts as an agonist on muscarinic-cholinergic receptors, stimulating secretion of saliva. This medication is licensed for use in the UK for dry mouth and eyes. A number of randomised controlled trials provided evidence of its efficacy in improving symptoms and showed objective increase in salivary flow in patients[26],[27],[28]

. However, there are contraindications to this medication, including irritable bowel syndrome, asthma and cardiac disease. Side effects are common and dose-dependent. They include sweating, palpitations and flushing. It can take up to 12 weeks to see a therapeutic benefit and some patients might not find this medication beneficial. National guidelines recommend a trial of pilocarpine 5mg once daily, increasing stepwise to 5mg four times daily, for patients with severe symptoms of oral dryness, as long as there are no contraindications to its use and the patient can tolerate the side effects[29]

.

Cevimeline is another muscarinic agonist that stimulates saliva and tear production[30],[31]

. This medication is associated with fewer side effects compared with pilocarpine as it has higher affinity for muscarinic receptors located on lacrimal and salivary gland epithelium[32]

. However,y ei cevimeline is not currently licensed for use in the UK.

Treatment of oral candidiasis

Dry mouth patients have been shown to have high levels of Candida, even if oral hygiene is good, and recurrent oral candidiasis is a common problem in patients with dry mouth[33],[34]

. The presence of dentures and smoking promote an environment for recurrent and persistent Candida infections. Oral candidiasis can present as white plaques or erythematous patches in the mouth. The BSR guideline recommends the use of oral nystatin liquid 1ml five times daily for seven days[10]

. This treatment can be repeated for one week, every eight weeks, if the infection is recurrent. Systemic fluconazole 50mg once daily for 10 days is required to treat erythematous long-standing infections[29]

.

Candida can also infect the corners of the mouth, causing fissured erythematous lesions — angular cheilits (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Angular cheilits

Courtesy of Anwar R Tappunni and Nairn Wilson

In persistent angular cheilitis, saliva seeps from the corners of the mouth, causing the commissures of the lip to become ‘soggy’, encouraging the overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus

The recommended treatment for these lesions is topical application of miconazole for two weeks, using a clean cotton bud to apply to each side to prevent cross-contamination and persistence of infection[35]

. This condition may be aggravated by dentures that fail to restore vertical face height[17]

.

When to refer

Individuals with acute onset, severe and sustained (>3 months) dry mouth, together with individuals considered to have complex, multifactorial xerostomia should be referred to their dentist. Individuals found to require specialist care may be referred on to a specialist/consultant in oral medicine. Where there is no (or limited) access to specialist oral medicine services, specialists/consultants in oral surgery or oral and maxillofacial surgery may be willing to accept the referral of individuals with xerostomia.

References

[1] Oxholm P & Asmussen K. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome: the challenge for classification of disease manifestations. J Intern Med 1996;239:467–474. PMID: 8656139

[2] Navazesh M, Christensen CM & Brightman VJ. Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of salivary gland hypofunction. J Dent Res 1992;71:1363–1369. doi: 10.1177/00220345920710070301

[3] Fehrenbach MJ & Heering SW. Glandular tissue, Chapter 7 In: Illustrated head and neck anatomy 5th Ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier, pp158–170.

[4] Nanci A. Ten Cate’s Oral Histology 8th Ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier, pp275–276.

[5] Dawes C. Circadian rhythms in human salivary flow rate and composition. J Physiol 1972;220:529–545. PMCID: PMC1330775

[6] Ekström J. Autonomic control of salivary secretion. Proc Finn Dent Soc 1989;85:323–331. PMID: 2699762

[7] Visvanathan V & Nix P. Managing the patient presenting with xerostomia: a review. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:404–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02132.x

[8] Field A & Longman L. Tyldesley’s Oral Medicine 5th Ed. Oxford, Oxford Medical Publications.

[9] Ship J, Fox PC & Baum BJ. How much saliva is enough? ‘Normal’ function defined. J Am Dent Assoc 1991;122:63–69. PMID: 2019691

[10] Price EJ, Rauz S, Tappuni AR et al. The British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of adults with primary Sjögren’s syndrome, on behalf of the British Society for Rheumatology Standards, Guideline and Audit Working Group. Rheumatology 2017;56:e24–e48. doi: 0.1093/rheumatology/kex166

[11] Söderström U, Johansson I & Sunnegardh-Grönberg K. A retrospective analysis of caries treatment and development in relation to assessed caries risk in an adult population in Sweden. BMC Oral Health 2014;14:126. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-126

[12] Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279–1291. PMCID: PMC4581720

[13] Srinivasan M, Schimmel M, Riesen M et al. High-fluoride toothpaste: a multicenter randomized controlled trial in adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2014;42(4):333–340. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12090

[14] Walsh T, Worthington HV, Glenny AM et al. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010(1):CD007868. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007868.pub2

[15] Zero DT, Brennan MT, Daniels TE et al. Clinical practice guidelines for oral management of Sjögren disease: Dental caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc 2016;147(4):295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2015.11.008

[16] Amitha H & Munshi AK. Effect of chlorhexidine gluconate mouth wash on the plaque microflora in children using intra oral appliances. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1995;20:23–29. PMID: 8634191

[17] Radford DR & Wilson NHF. Advising denture wearers in the community pharmacy. Pharm J 2018; online. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2018.20204010

[18] Visvanathan V & Nix P. Managing the patient presenting with xerostomia: a review. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:404–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02132.x

[19] Furness S, Bryan G, McMillan R et al. Interventions for the management of dry mouth: non-pharmacological interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;9:CD009603. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009603.pub3

[20] Furness S, Worthington HV, Bryan G et al. Interventions for the management of dry mouth: topical therapies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(12):CD008934. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008934.pub2

[21] Tanzer JM. Xylitol chewing gum and dental caries. Int Dent J 1995;45(Suppl 1):65–76. PMID: 7607747

[22] Milgrom P, Ly KA, Tut OK et al. Xylitol pediatric topical oral syrup to prevent dental caries: a double-blind randomized clinical trial of efficacy. Archs Pediats Adol Med 2009;163:601–607. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.77

[23] Riley P, Moore D, Ahmed F et al. Xylitol-containing products for preventing dental caries in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:CD:010743. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010743.pub2

[24] Hooper P, Tincello DG & Richmond DH. The use of salivary stimulant pastilles to improve compliance in women taking oxybutynin hydrochloride for detrusor instability: a pilot study. Br J Urol 1997;80:414–416. PMID: 9313659

[25] Tincello DG, Adams EJ, Sutherst JR, Richmond DH. Oxybutynin for detrusor instability with adjuvant salivary stimulant pastilles to improve compliance: results of a multicentre, randomized controlled trial. BJU Int 2000;85:416–420. PMID: 10691817

[26] Vivino FB, Al-Hashimi I, Khan Z et al. Pilocarpine tablets for the treatment of dry mouth and dry eye symptoms in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose, multicenter trial. P92–01 Study Group. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(2):174–181. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.2.174

[27] Wu CH, Hsieh SC, Lee KL et al. Pilocarpine hydrochloride for the treatment of xerostomia in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome in Taiwan–a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Formos Med Assoc 2006;105:796–803. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60266-7

[28] Rhodus NL & Schuh MJ. Effects of pilocarpine on salivary flow in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1991;72:545–549. PMID: 1745512

[29] Price EJ, Rauz S, Tappuni AR et al. The British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of adults with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. On behalf of the BSR Standards, Guideline and Audit Working Group. Rheumatology 2017;56(7):e24–e48. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex166

[30] Yamada H, Nakagawa Y, Wakamatsu E et al. Efficacy prediction of cevimeline in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Rheum 2007;26(8):1320–1327. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0507-8

[31] Petrone D, Condemi JJ, Fife R et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of cevimeline in Sjogren’s syndrome patients with xerostomia and keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Arth Rheum 2002;46:748–754. doi: 10.1002/art.510

[32] Noaiseh G, Baker JF & Vivino FB. Comparison of the discontinuation rates and side-effect profiles of pilocarpine and cevimeline for xerostomia in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheum 2014;32:575–577. PMID: 25065774

[33] Rhodus NL, Bloomquist C, Liljemark W et al. Prevalence, density, and manifestations of oral Candida albicans in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Otolaryn 1997;26:300–305. PMID: 9343767

[34] Leung KC, McMillan AS, Cheung BP et al. Sjögren’s syndrome sufferers have increased oral yeast levels despite regular dental care. Oral Dis 2008;14:163–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01368.x

[35] Hernandez YL & Daniels TE. Oral candidiasis in Sjögren’s syndrome: prevalence, clinical correlations, and treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 1989;68:324–329. PMID: 2788854