Science Photo Library

Recent high-profile cases, such as those detailed in the Francis Report in 2013, have put an increased focus on making patients the priority in care[1]

. This is echoed in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s guideline on patient experiences in adult NHS services[2]

and the General Pharmaceutical Council’s ‘Standards for pharmacy professionals’[3]

. Treating patients with compassion, dignity and empathy is fundamental to the concept of person-centred care[4]

and, as a result, the NHS both values and expects staff to demonstrate these skills. However, it can be difficult to achieve this in time-constrained consultations.

Building a rapport with patients, having good communication skills and showing empathy all help to build trust[5]

, which, in turn, is important for[6]

:

- Encouraging patient disclosure;

- Enabling pharmacists to help patients understand their medicines;

- Exploring patients’ thoughts and feelings around their medicines;

- Identifying any problems.

Furthermore, studies have shown benefits associated with having an empathetic approach, for example, more favourable patient satisfaction[7]

and improved health outcomes, with patients more inclined to follow doctors’ recommendations[8]

. Benefits associated with compassionate care include: better treatment adherence; greater satisfaction and wellbeing among patients, as well as doctors experiencing elevated meaning in their job; lower depression rates; and lower burnout[9]

.

This article describes how pharmacists and other healthcare professionals can apply the principles of empathy effectively during interactions with patients to overcome potential barriers.

Empathy, sympathy and compassion

There are a variety of definitions for empathy, sympathy and compassion in the literature, and the terms are used interchangeably in everyday language.

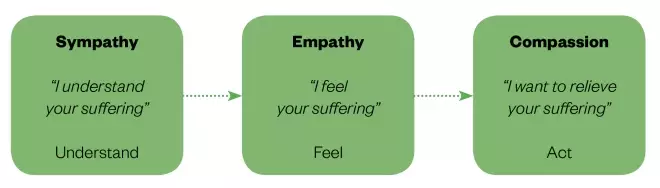

Empathy, as defined by the Cambridge Dictionary, is the ability to share someone else’s feelings or experiences by imagining what it would be like to be in that person’s situation[10] — often referred to as ‘walking in someone else’s shoes’. This is not to be confused with sympathy, which is when a person can understand what another person is feeling, but not feel what they feel. Compassion is considered to be one step further; it is when a person is moved by the suffering and distress of another and, consequently, feels a desire to act to relieve their suffering. Therefore, compassion arises from empathy but is characterised by action (see Figure). Compassion is considered a major motivator of altruism[11]

.

An important element of a patient–professional relationship is the need to understand and be understood. Empathy has been described as the most critical element in this therapeutic relationship — it has been suggested that empathy is not just an emotion or an inherent personality trait[6]

,[12]

, but much more complex involving emotive, moral, cognitive and behavioural aspects[13]

.

Figure: Basic overview of the relationship between sympathy, empathy and compassion

Source: The Pharmaceutical Journal

How to demonstrate empathy and compassion

Traditionally, pharmacists were trained to focus on patient counselling and instruction, which was seen as checklist-ticking, rather than a two-way dialogue and consultation that involved empathy[14],[15]

. However, when there has been a focus on the principles of teaching empathy, these skills have been found to increase[16]

, especially if emphasised through clinical placements[17]

.

Consider the patient

It is important to take a holistic view of the patient — physically, socially, culturally and psychologically. A patient’s work, family, social life and long-term health conditions can all have an impact on them. Jubraj et al. argues that applying clinical empathy, defined as “appropriate empathy demonstrated in a clinical setting”, can most effectively make use of the short time available in pharmacy consultations, therefore optimising care[18]

. Pharmacists do not have to agree with patients to demonstrate clinical empathy, rather empower them to take ownership of their treatment.

Question the patient effectively

In order to understand the patient’s perspective, ask them about their situation and create a common goal. This can be achieved through asking open-ended questions and clarifying responses through probing questions[19]

, such as “You said you haven’t been sleeping well — can you tell me more about that?”.

It is important not to make judgements about patients. For example, offering premature advice to a patient, before establishing how well informed they are about their condition and medicines, could have a negative impact and may leave the patient feeling patronised. Asking appropriate questions and listening to their answers should prevent this from happening and allow an opportunity to correct any misconceptions.

Pharmacists should summarise what patients say to check that their interpretation is accurate. In doing so, the pharmacist can contextualise and tailor the advice they deliver to the patient’s needs and capabilities. For example, this could be asking a patient “How do you feel about taking this medicine?” and “Do you have any concerns about taking it?”. If the patient expresses concerns, pharmacists should enquire further.

Reinforcing the message to be relayed with a politely articulated closing question, such as “Do you have any further questions?” or “Are you happy with this?”, will ensure the patient remains engaged and responsive to the dialogue (see Box 1).

Box 1: Demonstrating empathy and compassion in practice

Establish initial rapport

- Smile;

- Introduce yourself and apply the learning from the ‘Hello, my name is…’ campaign in daily practice;

- Demonstrate open body language, such as making eye contact and leaning forward slightly;

Establish the reason for the consultation

- Use open questions and show you are interested in what your patient has to say (e.g. by asking “What would you like to discuss today?”);

- Take time to listen to the patient — practice active listening and reflection, reiterating what the patient has said in your own words;

- Respect patient views, opinions, beliefs and feelings — avoid being judgemental;

- Acknowledge and deal with sensitive subjects by saying “I can see this is difficult for you”;

- However, avoid saying “I know how you feel” because this may provoke a negative response from the patient;

- Avoid interrupting the patient;

- Reflect a warm and open demeanour, and mirror feelings demonstrated by the patient through your posture and body language;

End the consultation

- Paraphrase the main points of the discussion;

- Be an advocate for the patient — make a phone call or follow up the query at a later date, for example, asking questions such as “What would help improve this for you?”

Listen to the patient

As well as listening to the patient, it is important to observe their non-verbal cues, such as their body language, tone of voice and manner of engagement. This will help with ascertaining their capacity, mental health, health literacy and comprehension of the exchange, along with any language issues that may be present. For example, closed body language (e.g. crossed arms or frowning) could indicate that they feel uncomfortable or challenged.

Using silence can also help — a pause in conversation may help a patient to provide more information.

Training

Various techniques have been used to teach empathy, including communication skills training, patient narratives, creative arts, drama and patient interviews[20]

. Compassion seems to be best developed through reflective and experiential learning, including learning from personal life experiences[21]

. As the pressures of work can be emotionally exhausting, it has been suggested that mindfulness interventions, such as ‘loving kindness’ meditation, have the potential to increase self-compassion, reduce stress and increase the effectiveness of clinical care[22]

(see Useful resources).

Challenges in providing compassionate care

Sinclair et al. identified several barriers to providing compassionate care across different healthcare professions, including lack of time, support, staffing and resources[21]

. Ideally, adjustments should be made at both an individual and an organisational level to alleviate pressured working environments and upskill healthcare professionals to facilitate greater empathetic and compassionate interactions with patients on a daily basis.

Workplace pressures

Lack of time:

- Heavy workload (e.g. high turnover of prescriptions);

- Low staffing levels:

- Not enough support staff in the dispensary;

- Not enough pharmacists to cover ward rounds;

- Being a single community pharmacist with high number of services to provide.

Organisational pressure:

- High level of targets to meet (e.g. medicines use reviews and the new medicine service);

- Limited time allocated to cover wards.

Imbalance of skill mix:

- May need accuracy-checking technicians to free up pharmacists’ time in the dispensary;

- May need a second pharmacist in community pharmacies.

Overcoming workplace barriers can be difficult — especially when the barriers are around staffing levels. However, even apologising to a patient who has been kept waiting, thanking them for their patience and providing a brief explanation for the delay can help to build rapport.

The patient

Language barriers:

- English not being their first language;

- Poor health literacy;

- Lack of understanding of medical jargon.

Disabilities:

- Hearing impairment, muteness or blindness;

- Learning disabilities.

Cultural barriers:

- Differences in health beliefs and behaviours;

- Different views on gender.

It is important to correctly tailor language to that of the patient, for example by avoiding the use of medical jargon. Providing the patient with information in a format they can read can also be useful — for example, patients with sight loss could benefit from large-print literature or Braille[23]

.

Underdeveloped consultation skills

Checklist-style of giving information:

- This ensures nothing is missed, but does not facilitate exploration of problems.

Using a ‘telling’ style associated with ‘advice-giving’ rather than a ‘consulting’ style of communication:

- This risks pharmacists appearing disrespectful by assuming the patient has limited knowledge and ability to self-manage their illness;

- This also risks the patient feeling patronised and, therefore, being may be less likely to follow advice.

Lack of confidence:

- This shows difficulty dealing with sensitive and embarrassing issues.

Practising these consultation skills while demonstrating empathy and compassion should help in overcoming these barriers.

Despite the many barriers that may exist or arise, empathy and compassion should ideally be demonstrated and practised in every patient encounter. A focus on empathy and compassion should be a component of undergraduate curricula in order to start developing these skills in foundational learning. Where relevant, professional development courses could emphasise the importance of an empathetic and compassionate approach necessary in building rapport. Interacting in this way will help pharmacists reach a shared understanding with patients as equal partners, prior to any shared decision-making[24]

.

Box 2 shows two case studies with suggested dialogues/questions.

Box 2: Case studies and example dialogues

Case study 1

A 35-year-old female patient has recently been diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML). After a series of lengthy tests which have made her anxious, she has been prescribed medicines.

She approaches the pharmacist to ask about side effects and what to anticipate in terms of the impact of the medicine on her quality of life.

The pharmacist has already spent longer than planned on the ward and was expected in the dispensary 15 minutes ago.

Example dialogue of an unempathetic approach to the patient

Patient: “Hi, I wonder if you could help? I’ve been diagnosed with CML and I have some questions about the side effects of the medicine, imatinib. I was told that a pharmacist could maybe go through it with me?”

Pharmacist: “Sorry, I’m running late. The possible side effects of imatinib include: alopecia, anaemia, chills, constipation, cough, diarrhoea, dizziness, dry eye, dry mouth, fever, headaches, vomiting and vision blurring. Sorry, I need to see my patients.”

In this scenario, the pharmacist responds to the first enquiry about the potential side effects of the medicine by reading off a list. He shrugs off the second query by stepping away from the dialogue under the guise of needing to attend to another query. The patient is left to ponder where to find an answer to her enquiry.

Example dialogue of a more empathetic approach to the patient

Patient: “Hi, I wonder if you could help? I’ve been diagnosed with CML and I have some questions about the side effects of the medicine, imatinib. I was told that a pharmacist could maybe go through it with me?”

Pharmacist: “I understand how anxious you must be. I’d really like to sit down with you to explain, as there is a lot to cover, but right now I have to report back to the pharmacy. Would you be available around 16:00 when my shift changes? I could come back and discuss these questions you have.”

Patient: “That would be great, thank you.”

Pharmacist: “Ok great, I’ll book a consultation room for half an hour to allow you some privacy and we can explore any questions you may have. Have your questions ready for then. See you at 16:00. I’ll come back to the ward to find you.”

In this scenario, the pharmacist engages with the patient and empathises with her anxiety in both appropriate verbal communication and body language. He makes an effort to find a solution for her, rather than walking away.

Case study 2

A 48-year-old male patient, Mike, rushes into the community pharmacy half an hour outside the agreed contractual time period to collect his methadone prescription. He is a quiet, withdrawn man with mental health issues and does not usually talk to the staff.

It is late in the day and the pharmacy is full of customers. Unknown to the pharmacist, the patient has been visiting his terminally ill mother in hospital, which is two bus rides away.

Example dialogue of an unempathetic approach to the patient

On his arrival, the community pharmacist immediately comes out from the dispensary, infuriated as it is the third time this week that the same patient has been late. The pharmacist asks angrily:

Pharmacist: “What time do you call this? You should have been here half an hour ago. If you’re late again, you’ll have to find a new pharmacy to take your prescription to!”

The patient looks embarrassed and mumbles an apology.

Example dialogue of a more empathetic approach to the patient

The pharmacist sees the patient rush into the pharmacy, flustered. He usually collects his methadone within the contracted time, so the pharmacist wonders why he has been late so often this week as it is out of character.

1. Establish initial rapport

The pharmacist approaches him directly and speaks to him in a calm tone.

Pharmacist: “Hello Mike. You seem to be finding it difficult to get here on time this week. That’s unusual for you. Is there anything you’d like to talk to me about?”

The patient finds it difficult to make eye contact and mumbles something incoherently.

Pharmacist: “Would you like us to go into the consultation room for a quick chat?”

2. Establish the reason for his late arrivals

The patient nods and follows. The pharmacist sits in the consultation room with open body language.

Pharmacist: “What’s the matter? Is there anything you’d like to talk about?”

Patient: “It’s my mum. She’s really ill now and they’re keeping her in hospital.”

The pharmacist shows concern in their expression but waits to allow the patient to tell them more.

Patient: “I’ve been going to visit her every day, but I don’t think she’s going to get better.”

The pharmacist acknowledges the difficult situation.

Pharmacist: “This must be really difficult for you, Mike.”

Patient: “It is. The hospital is really far too. It’s two bus rides away so that’s why I’ve been late.”

The pharmacist demonstrates active listening by reiterating what they heard.

Pharmacist: “Two bus rides each way and going every day — that must be very tiring for you too.”

The patient nods.

3. Ending the consultation

Pharmacist: “Don’t worry about the time you get to the pharmacy, Mike. Just get here when you can. Is there anything else I can do to help you?”

Patient: “There is actually. I forgot to order my risperidone and I only have a couple of days left.”

The pharmacist acts as an advocate for the patient.

Pharmacist: “Leave that with me, I’ll call the doctor and see what can be done.”

Useful resources

- Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. Consultation skills for Pharmacy Practice: http://www.consultationskillsforpharmacy.com/

- How to practice loving kindness meditation: https://www.verywellmind.com/how-to-practice-loving-kindness-meditation-3144786

References

[1] Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: The Stationary Office; 2013

[2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services. Clinical guideline [CG138]. 2012. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/Cg138 (accessed April 2019)

[3] General Pharmaceutical Council. Standards for pharmacy professionals. 2017. Available at: https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/standards_for_pharmacy_professionals_may_2017_0.pdf (accessed April 2019)

[4] The Health Foundation. Person-centred care made simple: what everyone should know about person-centred care. 2016. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/PersonCentredCareMadeSimple.pdf (accessed April 2019).

[5] Allinson M & Chaar B. How to build and maintain trust with patients. Pharm J 2016;297(7895). URI: 20201862

[6] Kunyk D & Olson J. Clarification of conceptualizations of empathy. J Adv Nurs 2001;35(3):317–325. PMID: 11489011

[7] Kim SS, Kaplowitz S & Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof 2004;27(3):237–251. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267037

[8] Del Canale S, Louis DZ, Maio V et al. The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: an empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy. Acad Med 2012;87(9):1243–1249. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf

[9] Post SG. Compassionate care enhancements: benefits and outcomes. Int J Pers Cent Med 2011;1(4):808–813. doi: 10.5750/ijpcm.v1i4.153

[10] Cambridge Dictionary. Empathy. 2019. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/empathy (accessed April 2019)

[11] Burton N. Heaven and Hell: The Psychology of Emotions. London: Acheron Press; 2015

[12] Reynolds W & Scott B. Empathy: a crucial component of the helping relationship. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 1999;6(5):363–370. PMID: 10827644

[13] Morse J, Anderson G, Botter J et al. Exploring empathy: a conceptual fit for nursing practice?Image J Nurs Sch 1992;24(4):273–280. PMID: 1452181

[14] Latif A, Pollock K & Boardman HF. The contribution of the medicines use review (MUR) consultation to counselling practice in community pharmacies. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83(3):336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.007

[15] Barnett N, Varia S & Jubraj B. Medicines adherence: are you asking the right questions and taking the best approach? Pharm J 2013;291:153–156. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2013.11126181

[16] Winefield HR & Chur-Hansen A. Evaluating the outcome of communication skill teaching for entry-level medical students: does knowledge of empathy increase? Med Ed 2000;34(2):90–94. PMID: 10652060

[17] Branch WT Jr, Kern D, Haidet P et al. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA 2001;286(9):1067–1074. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1067

[18] Jubraj B, Barnett NL, Grimes L et al. Why we should understand the patient experience: clinical empathy and medicines optimisation.Int J Pharm Pract 2016;24(5):367–370. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12268

[19] Davis CM. What is empathy, and can empathy be taught? Phys Ther 1990;70(11):707–711. PMID: 2236214

[20] Batt-Rawden SA, Chisholm MS, Anton B & Flickinger T. Teaching empathy to medical students: an updated systematic review. Acad Med 2013;88(8):1171–1177. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299f3e3

[21] Sinclair S, Norris JM, McConnell SJ et al. Compassion: a scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:6. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0080-0

[22] Raab K. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and empathy among healthcare professionals: a review of the literature. J Health Care Chaplain 2014;20(3):95–108. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2014.913876

[23] Barnett N, El Bushra A, Huddy H et al. How to support patients with sight loss in pharmacy. Pharm J 2017;299(7904). URI: 20203346

[24] Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. Consultation skills for pharmacy practice. 2018. Available at: http://www.consultationskillsforpharmacy.com/ (accessed April 2019)