Shutterstock

There are more than 200 eye conditions, ranging from common problems (e.g. dry eye disease [DED], cataracts and glaucoma) to rarer diseases (e.g. ocular melanoma and vernal keratoconjunctivitis). Some of these have no symptoms and can cause loss of sight before patients even realise what is happening. There are 1.8 million people in the UK who are living with significant sight loss, 50% of which is avoidable[1]

. As such, the government’s Public Health Outcomes Framework has highlighted preventable sight loss as a health priority[2]

.

There are many services that pharmacists and healthcare professionals can signpost patients to that support the aim of reducing the incidence of preventable sight loss. This article describes how to identify patients in at-risk groups and counsel them on lifestyle changes and the treatments that are available. It also outlines the ‘red flag’ symptoms as well as when and where to refer patients.

1. Reduce alcohol consumption

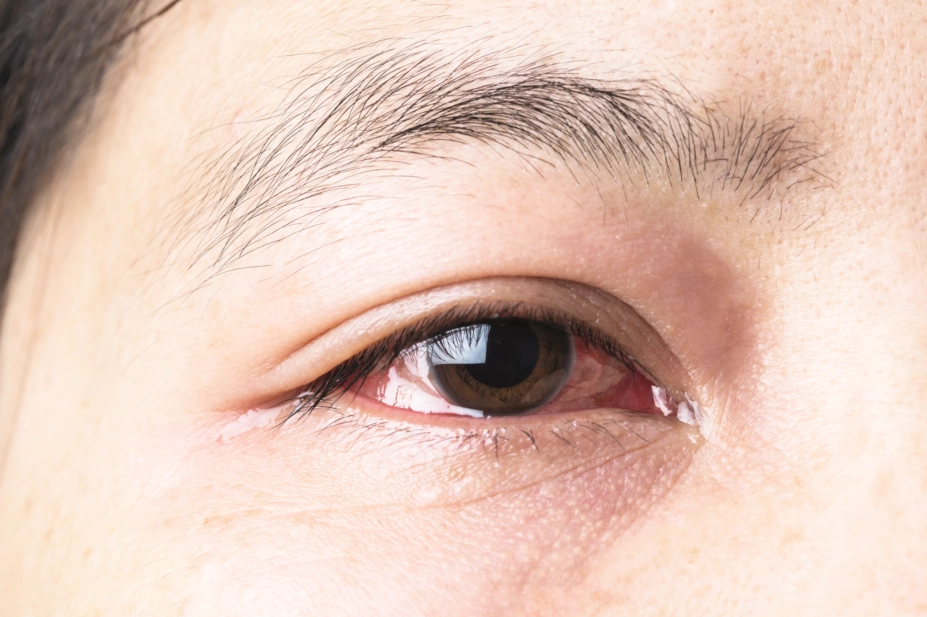

In addition to increasing the risk of heart disease, liver disease and certain cancers, persistent alcohol misuse can also affect long-term eye health. Alcohol use has been shown to exacerbate the signs and symptoms of DED (also known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca)[3]

, a condition where the eyes do not make enough tears or the tears evaporate too quickly, leading to the eyes drying out and becoming red, swollen and irritated (see Box 1). A case–control study in ten patients following ethanol ingestion demonstrated that ethanol was detected in the person’s tears and was associated with a decreased tear break-up time (through ethanol acting as a solvent), increasing tear osmolarity and disturbing cytokine production[4]

.

Box 1: Dry eye disease

The common chronic condition dry eye disease (DED) is estimated to affect between 1 in 3 and 1 in 20 people[5]

.

Symptoms, which usually affect both eyes, include:

- Irritation;

- Grittiness (the feeling that there is sand in the eye);

- Burning;

- Soreness;

- Watery eyes;

- Visual disturbance.

Patients who present with the following symptoms should be referred to their GP or an eye care specialist:

- Severe or sudden pain in one or both eyes;

- Sudden onset of symptoms after a certain event;

- Mouth dryness in combination with other dry eye symptoms (this can be a sign of Sjögren’s disease);

- Loss of vision or serious visual disturbance (a symptom of retinal detachment).

For more information on identifying DED and treatment recommendations in the community pharmacy setting, see Wolffsohn et al.’s ‘Identification of dry eye conditions in community pharmacy’[3]

and Evans & Madden’s ‘Recommending dry eye treatments in community pharmacy’[6]

.

Heavy alcohol consumption has also been associated with known causes of blindness, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD; when the cells in the central part of the retina become damaged and central vision is impacted as a result). A meta-analysis of five published studies found that heavy alcohol consumption, defined as an intake of ≥30g of alcohol/day, was associated with an increased risk of early AMD[7]

. Alcohol is thought to increase oxidative stress by modifying the mechanisms that protect against it, resulting in AMD[7]

. The link with cataracts (clouding of the lens in the eye) is less clear, but an increased prevalence of cataracts has been reported in patients with heavy alcohol consumption[8]

.

Pharmacists should counsel patients in accordance with current NHS guidance: people should not drink more than 14 units of alcohol (a unit of alcohol is defined as 10mL of pure alcohol, roughly equivalent to 8g) per week and alcohol consumption should be evenly spread over three or more days, with several alcohol-free days each week[9]

. Patients can be signposted to organisations that can help provide support alongside the NHS, including Alcohol Concern, Alcoholics Anonymous and Drinkaware.

2. Quit smoking

A history of cigarette smoking has been associated with an increased risk of AMD and is related to both its incidence and progression[10]

. Current smokers have been shown to be at an increased risk of developing AMD, compared with ex-smokers and non-smokers who are exposed to second-hand smoke[11]

. Cigarette smoke has also been shown to have a dose-related relationship with the formation of cataracts[12]

. It has also been linked to diabetic retinopathy (the blockage of blood vessels at the back of the eye), DED and glaucoma (a condition affecting the optic nerve).

A cross-sectional survey of 260 teenagers found that fear of blindness was just as compelling a motivation for smoking cessation as fear of lung cancer, heart disease and stroke[13]

. Discussions relating to eye care could, therefore, help motivate patients to quit smoking.

Pharmacists and healthcare professionals should enquire on the smoking status of all patients at least once per year and should discuss it during routine consultations. They can even provide advice to patients outside of smoking cessation services or the provision of nicotine replacement therapy, including during the purchase of over-the-counter (OTC) medicines, through medicines use reviews or during local or national campaigns (e.g. No Smoking Day).

3. Protect eyes from the sun

High levels of exposure to ultraviolet (UV) A and B light are known risk factors for numerous eye conditions, including cataracts and cancer[14]

. Most brands of prescription glasses now contain a UV filter, but not all sunglasses provide adequate protection. Patients should be counselled to ensure their sunglasses are either CE or BS marked (i.e. proof of conformity with European or British standards, respectively), and are the appropriate filter category for their use (filter categories range from 0 to 4, where 4 is the darkest lens). For further advice, see Box 2.

Box 2: Advice pharmacists can give patients on buying sunglasses

- Sunglasses should carry the CE mark and British Standard, which ensures they offer a safe level of ultraviolet (UV) protection;

- Sunglasses that will be worn for driving should be in the filter category range of 0–3. A lens carrying a filter category of 4 will be too dark for safe driving;

- Unless the glasses carry the British Standard BS EN 1836:1997, the shade of the lenses should not be confused with their ability to filter UV rays. Dark sunglasses may still allow UV rays to enter the eye and can be more harmful than wearing no glasses at all because they cause the pupil of the eye to dilate, allowing more UV rays to enter;

- Sunglasses will also absorb high energy visible radiation (blue light). It is recommended that no more than 95% of blue light should be filtered to avoid colour distortion.

Source: The British Standards Institution. Sunglasses – not just about looking cool in the heat. 2002. Available at: https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/about-bsi/media-centre/press-releases/2002/6/Sunglasses—not-just-about-looking-cool-in-the-heat/ (accessed November 2018)

4. Reduce screen time

Increasing reliance on digital devices has led to a rapid increase in computer-related eye symptoms, known as computer vision syndrome (CVS)[15]

. Symptoms of CVS can be divided into four categories:

- Eye strain (asthenopia);

- Dry or painful eyes relating to the ocular surface[3],[16]

; - Difficulty focusing (visual blur);

- Other non-ocular symptoms[15]

.

For patients experiencing CVS, a range of pharmacy medicines are available over the counter, along with environmental management options, such as:

- For symptoms of fatigue, everyone using screens should be advised to follow the 20:20:20 rule (every 20 minutes individuals take a 20-second break and focus on an object 20 feet away)

- Modify the screen environment, taking into account lighting and glare, airflow, screen and seating configuration and blue light.

- Refering patients with blurred vision to an optometrist

- If difficulty focusing is a problem, patients should be advised of the Health and Safety Executive guidance (i.e. that employers have to provide an eye test if an employee habitually uses display screen equipment as a significant part of their normal day-to-day work).

- Following advice for mild aqueous-deficient DED

- Treat with artificial tears and ocular lubricants;

- Although hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (hypromellose) is commonly recommended, a more viscous product, such as carbomer 980, may be helpful for patients with CVS because they can increase the time that moisture is retained;

- Moderate-to-severe symptoms may require prescribed topical anti-inflammatory medications (e.g. ciclosporin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory eye drops or corticosteroid eye drops);

- Sodium hyaluronate is often recommended for treatment of more advanced DED.

- Following advice for evaporative DED

- Ocular lubricants may ease symptoms.

- Modifying the screen environment, taking into account the following factors

- Lighting and glare;

- Airflow;

- Screen and seating configuration;

- Exposure to blue light.

- For patients with double vision, refer to an orthoptist[15]

.

OTC treatments for eye conditions are available in a range of formulations, including sprays, drops, gels and ointments. Patients should be advised of the various products, their potential modes of action and administration methods, to allow them to make an informed decision. For further advice, see Barai and Hammond’s ‘Computer vision syndrome: causes, symptoms and management in the pharmacy’[15]

.

5. Have regular sight tests

Pharmacists can reinforce the importance of regular sight tests; for the majority of adults, the recommended interval is every two years[17]

. However, some higher risk patient groups are recommended to have more frequent sight tests (see Box 3). Some patient groups also have additional risk factors for glaucoma (e.g. Afro–Caribbean or Asian patients, or patients who are aged 40 years and over with a family history, are living with diabetes or high blood pressure, or are taking systemic or topical corticosteroids). These patients should be signposted to their local optician if they have not had a recent sight test or have any vision concerns.

Similarly to exemptions from NHS prescription charges, some patient groups are exempt from paying for sight tests. It is worth checking with patients to see if they qualify[18]

.

Box 3:

Recommended sight test frequency

- Test every six months:

- People aged under 7 years with binocular vision anomaly or corrected refractive error (i.e. have a squint or require glasses to correct vision);

- People aged 7–15 years with binocular vision anomaly or rapidly progressing myopia (i.e. have a squint or are short-sighted).

- Test every year:

- People up to the age of 16 years who have no binocular vision anomaly or refractive error (i.e. no squint or do not require glasses to correct vision);

- People with diabetes who are not part of a diabetic retinopathy monitoring scheme.

- Test every two years:

- People aged 16 years and over;

- People with diabetes who are part of a diabetic retinopathy monitoring scheme.

Source: College of Optometrists. Knowledge skills and performance domain/The routine eye examination. 2017

[17]

6. Follow contact lens hygiene advice

Owing to the nature of introducing a foreign item onto the surface of the eye, and the warm and moist environment in the eye, improper use of contact lenses can lead to problems. Pharmacists should be aware of The Association of Optometrists’s advice for contact lens wearers in order to counsel patients effectively:

- Hands should be washed and dried before handling contact lenses;

- Tap water should never be used to clean lenses (Acanthamoeba is found in tap water, which can lead to sight-threatening infections);

- A specific type of contact lens solution should be used, as advised by an optometrist;

- Contact lens cases should be cleaned weekly with lens solution and replaced monthly when a new bottle of lens solution is opened. The solution in the case should be changed after each lens wear;

- Never swim or bathe while wearing contact lenses unless advised by an optometrist or eye care practitioner that it is safe to do so;

- Never share or swap lenses;

- Apply makeup after putting in lenses and remove once lenses removed;

- Never wear lenses for longer than recommended (maximum 16 hours/day) as this increases the risk of microbial keratitis and DED;

- Never sleep in lenses unless they are specifically designed for overnight wear;

- Go to regular aftercare appointments (at least annually);

- Consult an optometrist in the event of redness, pain or loss of vision;

- If in doubt, take them out[19]

.

7. Attend screening

All patients taking hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine should receive regular eye screening owing to the risk of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy, as stipulated by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists[20]

. At least 7.5% of patients taking hydroxychloroquine for more than five years will have some retinal damage. Hydroxychloroquine screening schemes are still being developed across the UK; however, it is still important to remind patients about the importance of regular eye screening. The rule of five is a helpful reminder: if patients are taking more than 5mg/kg/day for more than five years, then annual eye screening is required[20]

.

8. Practise good eye drop compliance and technique

Around 50% of patients with glaucoma are non-compliant with treatment[21]

. Given the consequences of treatment failure, pharmacists should consider reasons for this and assist patients to overcome any barriers they may have; this will help prevent poor clinical outcomes and potentially unnecessary polypharmacy. The case study in Box 4 demonstrates how to do this.

Box 4:

Eye drop compliance and technique case study

Mrs G comes to collect her repeat medication (metformin and ramipril) from the pharmacy. You note she also has latanoprost eye drops on her repeat medications, but has not requested these for some time. You decide to ask her about her eye drops, she states she no longer needs them as she does not have any symptoms and her glaucoma has “got better”.

How to approach the situation

Glaucomatous damage is irreversible so it is important to highlight that glaucoma is a broadly symptomless disease. Intraocular pressure needs to be controlled in the long term, and kept below 24mmHg to prevent visual problems as a result of damage to the optic nerve.

As Mrs G also has diabetes and hypertension, she is at higher risk of glaucoma; therefore, it is important that all three conditions are adequately controlled. Following your discussion, it becomes apparent that Mrs G did not understand the importance of continuing to use the eye drops until her ophthalmologist agrees her intraocular pressure is acceptable or she is no longer at risk of developing visual loss within her lifetime[22]

.

What else to assess

It is important to check eye drop technique. Consider the wrist–knuckle technique developed by the Moorfields eye hospital #knowyourdrops campaign team[23]

:

- Check the expiry date on the eye drop bottle and shake if required;

- Wash your hands before opening the bottle;

- Lie down or sit down and tilt your head back;

- Make a fist with one hand and use your knuckles to pull your lower eyelid downwards. Hold the eye drop bottle with your other hand, and place your wrist on your knuckles;

- Look up and squeeze one drop into your lower eyelid, making sure the nozzle does not touch your eye, eyelashes or eyelid;

- Close your eye and press gently on the inner corner of your eye for 30–60 seconds to ensure the drop is fully absorbed.

When to refer

OTC treatment of common eye problems in the pharmacy is often limited to management of red, sticky, gritty and sore eyes. However, pharmacists should have a good awareness of how to treat DED and bacterial conjunctivitis[6],[24]

, and recognise red flag symptoms (e.g. visual loss; pain; flashing lights, floaters or halos; headaches; and co-existing diabetes or hypertension).

Where established, minor eye condition schemes (MECS) involve local accredited opticians or optometrists who offer urgent appointments (see Table 1 for an overview). Patients can self-refer or be referred by a pharmacist, GP or NHS 111. Those participating in the MECS can refer patients to eye casualty or hospital eye services if required[25]

. Pharmacists are advised to check the details of MECS in their area for a definite list of referral criteria.

| Table 1: Which service patients with eye problems should attend | ||

| GP | Minor eye condition service | Eye casualty |

| Swollen eye and fever (urgent) | Painful eye* | Penetrating eye injury/eye trauma |

| Visual changes linked to headache (e.g. migraine) | Foreign body in eye | Sudden or dramatic vision changes |

| Flashing lights* | Eye pain interfering with activities of daily living | |

| Floating dots* | Eye pain with eye bulging | |

| Ingrowing eyelashes | Eye surgery within the past 30 days in the same eye | |

| Painful red eye with reduced vision/light sensitivity | ||

| Painful red eye with vision loss and nausea/vomiting | ||

| History of uveitis/iritis plus suspicion of a new episode | ||

| Vision loss with headaches and scalp/jaw soreness | ||

| Painful eye with droopy eyelid/double vision/abnormal pupil | ||

| Contact lens wear with red eye/severe pain/reduced vision | ||

| Flashers or floaters with veils/curtains/clouds, or reduced central vision | ||

| *Recent issue within the past six weeks Source: Oxfordshire Local Optical Committee. Patient information leaflet for minor eye conditions scheme[26] | ||

Supported by RB

RB provided financial support in the production of this content.

The authors were paid by The Pharmaceutical Journal to write this article and full editorial control was maintained by the journal at all times.

References

[1] Royal National Institute of Blind People. Sight loss: a public health priority. 2014. Available at: https://www.rnib.org.uk/sites/default/files/Sight_loss_a%20public_health_priority_1401.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[2] Department of Health. Improving outcomes and supporting transparency. Part 2: Summary technical specifications of public health indicators. 2016. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545605/PHOF_Part_2.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[3] Wolffsohn J, Bilkhu P, Wolffsohn T & Langley C. Identification of dry eye conditions in community pharmacy. Pharm J 2016;297(7892):S7–S10. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20201138

[4] Kim JH, Kim JH, Nam WH et al. Oral alcohol administration disturbs tear film and ocular surface. Ophthalmology 2012;119(5):965–971. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.11.015

[5] Wolffsohn J & Craig JP. Evidence-based understanding of dry eye disease in pharmacy: overview of the TFOS DEWS II report. Pharm J 2017;299(7905):166–170. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2017.20203352

[6] Evans K & Madden L. Recommending dry eye treatments in community pharmacy. Pharm J 2016;297(7892):S11–S14. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20201430

[7] Chong E, Kreis A, Wong T et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of age-related macular degeneration: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;145(4):707–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.12.005

[8] Wang S, Wang JJ & Wong TY. Alcohol and eye diseases. Surv Ophthalmol 2008;53(5):512–525. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.06.003

[9] Department of Health. UK chief medical officers’ low risk drinking guidelines. 2016. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[10] Chakravarthy U, Augood C, Bentham G et al. Cigarette smoking and age-related macular degeneration in the EUREYE Study. Ophthalmology 2007;114(6):1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.09.022

[11] Khan JC, Thurlby DA, Shahid H et al. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: the number of pack years of cigarette smoking is a major determinant of risk for both geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90(1):75–80. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.073643

[12] Klein BE, Klein R, Linton KL et al. Cigarette smoking and lens opacities: the Beaver Dam Eye study. Am J Prev Med 1993;9(1):27–30. PMID: 8439434

[13] Moradi P, Thornton J, Edwards R et al. Teenagers’ perceptions of blindness related to smoking: a novel message to a vulnerable group. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91(5): 605–607. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.108191

[14] Cruickshanks K, Klein B & Klein R. Ultraviolet light exposure and lens opacities: the Beaver Dam Eye study. Am J of Public Health 1992;82(12):1658–1662. PMCID: PMC1694542

[15] Barai J & Hammond C. Computer vision syndrome: causes, symptoms and management in the pharmacy. Pharm J 2017;299(7908):363–366. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2017.20203789

[16] Connelly D. Dry eye: pathology and treatment types. Pharm J 2016;297(7892):S2–S3. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20201582

[17] The College of Optometrists. The routine eye examination. 2017. Available at: http://guidance.college-optometrists.org/guidance-contents/knowledge-skills-and-performance-domain/the-routine-eye-examination/ (accessed November 2018)

[18] Association of Optometrists. NHS sight test eligibility. 2017. Available at: https://www.aop.org.uk/advice-and-support/for-patients/nhs-funded-eye-sight-test-eligibility-and-voucher-guide (accessed November 2018)

[19] Association of Optometrists. Contact lens advice: soft contact lenses. 2017. Available at: https://www.aop.org.uk/advice-and-support/for-patients/contact-lenses/soft-lenses (accessed November 2018)

[20] The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Clinical guidelines: Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine retinopathy screening guideline recommendations. 2018. Available at: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Hydroxychloroquine-and-Chloroquine-Retinopathy-Screening-Guideline-Recommendations.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[21] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. #KnowYourDrops eye drop compliance campaign to achieve medicines optimisation in ophthalmology. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/sharedlearning/knowyourdrops-eye-drop-compliance-campaign-to-achieve-medicines-optimisation-in-ophthalmology (accessed November 2018)

[22] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Glaucoma: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG81]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng81/chapter/Recommendations#treatment (accessed November 2018)

[23] Moorfields Eye Hospital. Patient information general: how to use your eyedrops. 2018. Available at: https://www.moorfields.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/How%20to%20use%20your%20eye%20drops_0.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[24] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Chloramphenicol 1% ointment/0.5% eyedrops: quick reference guide. 2017. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/quick-reference-guides/chloramphenicol-05w-v-eye-drops-1w-v-ointment (accessed November 2018)

[25] Local Optical Committee Support Unit. Minor eye conditions service pathway. 2014. Available at: http://www.locsu.co.uk/community-services-pathways/primary-eyecare-assessment-and-referral-pears/ (accessed November 2018)

[26] Oxfordshire Local Optical Committee. Patient information leaflet for minor eye conditions scheme. 2018. Available at: https://www.oxfordshireloc.org.uk/files/2115/3786/8581/Patient_Information_Leaflet_for_MECS_Oxfordshire__A5_Sept18.pdf (accessed November 2018)

You might also be interested in…

Health news round-up: NICE approvals, fighting AMR and medicines safety concerns

Dale and Appelbe’s Pharmacy and Medicines Law: covering ‘essential ground in the most highly regulated areas of healthcare’