Shutterstock

Fungal nail infection (onychomycosis [OM]) is a mycotic infection caused by fungal invasion of the nail structure[1]

and is one of the most common nail disorders, representing half of nail abnormalities in adults[2]

. Its prevalence in Europe is around 4.3% over all age groups[3]

and 15.5% of all nail dystrophies in children[4]

. OM is more commonly diagnosed in men and older people, affecting 20–50% of people aged over 60 years[5]

. An increased incidence among older people may be attributed to multiple factors, including reduced peripheral circulation, diabetes, inactivity, relative immunosuppression, and reduced nail growth and quality[6]

. Toenails are affected more commonly than fingernails.

This article will cover the causes, types and treatment of OM, practical information to help guide patient consultations and when to refer to podiatry.

Nail anatomy and onychomycosis infection

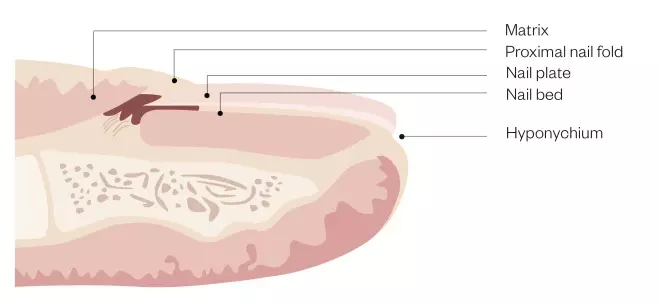

Figure 1 shows the composition of the nail, including the nail plate (the visible part of the nail), nail bed (the skin under the nail) and nail matrix.

Figure 1: Nail anatomy and physiology

The nail plate and nail bed are joined by layers of hard, translucent, keratinised cells. The nail bed and nail matrix are vascular components of the nail, with nail cells located within the nail matrix where the nail plate is formed. The thickness of the nail plate determines the length of the matrix

[7],[8]

.

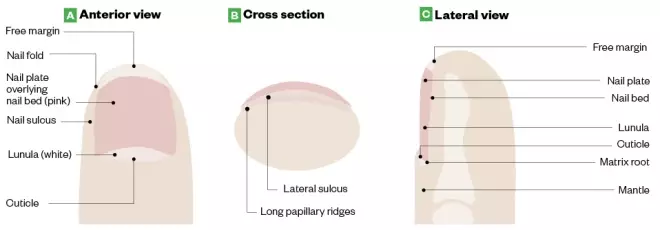

Damage to the nail structure can affect nail growth, shape, size and, consequently, predispose the nail to infection. OM can invade any part of the nail but typically enters the nail’s free edge, sulci or damaged cuticles (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Anatomy of a healthy toenail

Source: LeBlond RF, Brown DD, Suneja M & Szot JF. DeGowin’s Diagnostic Examination, 10th ed. McGraw-Hill

Onychomycosis can invade any part of the nail but typically enters the nail’s free edge, sulci or damaged cuticles.

Where OM infects the area underneath the nail plate, the infection produces a thick hyperkeratotic nodule that contains clusters of branching filaments (hyphae) called dermatophytoma (see Photoguide: A)[9]

. Consequently, the nail becomes severely deformed and can cause nail lifting, brittleness and discoloration, which may result in acute pain[10]

. The abnormal thickness of the nail may lead to soft tissue breakdown and/or infection resulting in inflamed subcutaneous tissue (cellulitis), ulceration in the nail bed (subungual ulceration) and/or bone infection (osteomyelitis)[10]

.

Causes

Dermatophytes

Around 85–90% of OM cases are caused by dermatophytes (fungal organisms that require keratin for growth), such as Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton

mentagrophtyes

[5],[11]

. Dermatophytes are highly resistant and can survive for long periods of time, especially in moist and dark environments[12],[13]

, which may explain why toenails are more susceptible to OM than fingernails.

Non-dermatophyte moulds

Around 2–5% of cases of OM are caused by non-dermatophyte moulds, such as Scopulariopsis, Scytalidium, Aspergillus, Fusarium and Acremonium species that typically affect toenails. Fingernails are rarely affected[5],[11]

.

Yeasts

Candida spp. is responsible for 5–10% of OM infections, affecting fingernails more often than toenails[14]

.

Photoguide: Types of onychomycosis

Source: Shutterstock.com / Courtesy of Marion Yau

Types of onychomycosis

Distal lateral subungual onychomycosis

The most common type of OM is distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO) (see Photoguide: B). It is characterised by build-up of soft yellow keratin between the nail plate and nail bed (subungual hyperkeratosis), detachment of the nail from the nail bed (onychosis) and skin infection around the nail (paronychia). DLSO spreads proximally to the nail matrix[15]

.

White superficial onychomycosis

Cases of white superficial onychomycosis (see Photoguide: C) are characterised by distinct white ‘islands’ on the nail surface, which gradually spread to the entire nail, causing it to become soft and crumbly[15]

.

Endonyx onychomycosis

White milky patches without subungual hyperkeratosis (build of keratin underneath the nail) indicate endonyx onychomycosis (EO) (see Photoguide: D). Pitting is involved with splitting of the nails. EO usually affects fingernails[15]

.

Proximal subungual onychomycosis

Affecting fingernails and toenails, proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO) (see Photoguide: E) is frequently found in, but not unique to, patients with HIV. The fungal infection begins at the cuticle and the nail fold before penetrating the nail plate. PSO is characterised by white discoloration that usually includes paronychia with some discharge[15]

.

Total dystrophic onychomycosis

The most advanced type of OM is total dystrophic onychomycosis (see Photoguide: F), which invades the nail plate, nail bed and nail matrix causing severe nail dystrophy. There can be chronic swelling at the distal phalanx with the affected nail appearing thickened, yellow-brown in colour and severely deformed[15]

.

Diagnosis

Despite OM having distinct clinical features, around half of nail dystrophy cases are caused by fungal infection and, therefore, clinical examination alone is rarely sufficient to diagnose OM[1]

.

Characteristics are shared with other nail diseases, such as psoriasis, lichen planus or bacterial infections (see Table 1). In addition to examining the nail(s) affected, pharmacists should ask the patient the following questions to help establish a diagnosis[16]

:

- How long have you had this condition?

- Do you have any skin disorders such as psoriasis, lichen planus, athlete’s foot?

- Have you had the nail tested for fungus or any nail diseases?

- Have you suffered any trauma?

- Do you have any family history of fungal nail infection?

- What is your occupation? (Jobs that involve the individual coming into contact with water may increase risk of OM)

- Do your nails/toenails hurt?

- Does the issue affect daily activities such as walking or standing?

Ideally, OM should be confirmed by direct microscopy and cultures to eliminate non-infective differential diagnosis, to identify mixed infections and to detect resistant OM[5],[17]

. Around 30% of culture examinations are reported as false negative[18]

and where OM is strongly suspected in the presence of a negative culture, the test should be repeated.

The British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) supports laboratory investigation prior to commencing oral treatment, which is in support of guidance from Public Health England (PHE)[5],[16]

. However, this guidance suggests that oral treatment can be offered despite negative findings if there is a strong clinical suspicion[5],[10],[15]

. Guidance for use of topical medications for DLSO is less clear and although investigations would present good practice, these treatments have minimal associated risks compared with oral treatment. However, incomplete sample collection could have a major impact on false negatives. Time constraints and continuity in working patterns should be considered as culture and microscopy results may take 2–6 weeks to come back.

| Clinical indicators | Description |

|---|---|

| Punctate leukonychia | White spots on the nails; leukonychia is total whitening of the nail plate |

| Trauma or injury | Very similar appearance of onychomycosis, causing the nail to lift from the nail bed (onycholysis), thicken (onychauxis) or develop white marking |

| Psoriasis | Pitting of the nails; yellow-red nail discolouration under the nail plate that resembles a drop of blood or oil |

| Lichen planus | Ridged nails, melanonychia, thinning of the nail plate and nail dystrophy |

| Yellow nail syndrome | Loss of cuticle, yellow-greenish discolouration of the nails with thickening and curvature |

| Anaemia | Abnormal shape of the fingernail (koilonychia) with thinning, raised ridges and an inward curve |

| Chronic eczema | Pitting of the nail with ridging, adjacent skin involvement with vesicles, scaling and erythema |

| Chronic renal failure | Proximal nail bed whiteness and distal nail bed red/pink/brown discolouration (called half and half nails); absent lunula and tiny blood clots under the nail (splinter haemorrhages) |

| Source: Neale’s Disorders of the Foot[19] , Onychomycosis (Tinea unguium, Nail fungal infection)[20] | |

On examination, pharmacists should consider the following factors and patient groups and it may be necessary to refer the patient to a podiatrist or their GP:

- The infection affects more than two nails or more than half of the nail;

- There is nail dystrophy or destruction;

- The nail condition appears to be other than DSLO (differential diagnosis by pharmacists is essential to ensure the patient received the right treatment — if there is any doubt of the diagnosis, the patient should be referred to a podiatrist or their GP);

- Patients with conditions that predispose them to fungal infections (e.g. immunosuppression, diabetes, peripheral circulatory disorders);

- Pregnant or breastfeeding women;

- Patients aged under 18 years;

- If there is no improvement after three months of treatment.

Treatment

The management of OM depends on the type, extent and severity of nail involvement, symptoms and pre-existing conditions. The aim of treatment is to eradicate the pathogen, restore the nail and prevent re-infection. OM is challenging to treat and affected nails may never return to normal as the infection may have caused permanent damage.

As OM has a high relapse rate of 40–70%[5]

, advice on preventative and appropriate self-care strategies to avoid re-infection should be offered to patients.

Topical treatments

The compact and hard nature of the nail anatomy means topical drug penetration can be poor, with the concentration reducing by 1,000 times from the outer to inner areas[5]

.

The BAD advises the use of monotherapy topical antifungal agents to be restricted to:

- Superficial white onychomycosis (except for transverse or striate infections);

- Early DLSO (except where longitudinal streaks exist) without lunula involvement and where less than 80% of the nail plate is affected;

- When systemic antifungals are contraindicated.

Amorolfine

The only topical nail lacquer available in the UK for over-the-counter (OTC) purchase is amorolfine. It is licensed for mild (not more than two nails affected) DLSO and patients aged 18 years or over. Amorolfine is a broad-spectrum synthetic fungicidal with high activity against dermatophytes, as well as other fungi, yeasts and moulds. It is available as a 5% lacquer that should be applied once or twice per week[16],[21]

. PHE recommend a treatment duration of 6 months for fingernails and 12 months for toenails, so adherence is essential[16]

.

Before application, patients should be advised to file down the affected nail surfaces using a single-use nail file, clean the nail surface with the supplied swab and dry the nail surface[16]

. Patients should be reminded that this process should be repeated for sequential treatments; a step that is commonly missed out. Sterile cotton buds should be used to apply the lacquer to avoid contamination.

Amorolfine maintains clinical efficacy in the nail for 14 days after treatment; however, twice-weekly application results in better outcomes compared with once-weekly application (71% versus 76% mycological cure)[22],[23]

. Compliance is essential; pharmacists should encourage patients to continue the treatment, given the prolonged treatment duration of 6–12 months. Side effects are rare and limited to nail disorders (e.g. discolouration, and broken and brittle nails), which may be related to OM itself.

Tioconazole

The BAD recommends tioconazole, a prescription-only medicine (POM), for superficial and distal OM[5]

. Tioconazole is an imidazole derivative with a broad spectrum of action against dermatophyte and yeast-like fungal species. It is available as a 283mg/mL medicated nail lacquer and is applied to affected nails twice a day. Treatment duration ranges from 6–12 months depending on the pathogen, the severity and the location of the infection. Common side effects include mild and transient local irritation that usually presents during the first week of treatment[24]

.

Systemic therapy

For adults with confirmed OM, systemic therapy is advised when self-care strategies with or without topical therapy are unsuccessful or inappropriate. A recent Cochrane systematic review of oral antifungal treatments for toenail OM in more than 10,000 patients found high-quality evidence indicating that terbinafine and azoles were effective treatments for mycological and clinical cure compared with placebo[11]

.

Terbinafine and itraconazole are considered the mainstay of oral therapy for OM, although terbinafine is generally preferred over itraconazole owing to better cure rates compared with azole in toenail OM[11],[16]

. Other systemic therapies are available (see Table 2).

| Treatment | Contraindication and cautions | Dosing | Monitoring | Common adverse reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terbinafine (first or second line) | Risk of developing lupus erythematosus-like effect; worsens symptoms of psoriasis | 250mg/day for 6 weeks (fingernails) or 3–12 months (toenails) | Liver function: 4–6 weeks | Abdominal discomfort, anorexia, arthralgia, diarrhoea, dyspepsia, headache, myalgia, nausea, rash, urticaria[25] |

| Itraconazole (first or second line) | Risk of heart failure; avoid giving to patients with ventricular dysfunction or heart failure | 200mg once daily for 3 months, then 200mg twice daily for 7 days, repeated at 21 days. Fingers require two courses, toes require three courses and persistent infections require an additional course of treatment | Liver function: 4–6 weeks | Abdominal pain, diarrhoea, dyspnoea, headache, hepatitis, hypokalaemia, nausea, rash, taste disturbances, vomiting[26],[27] |

| Fluconazole (third line) | Currently not licensed for use in onychomycosis | Fingernails: 150–450mg once per week for 3 months; toenails: 150–450mg once per week for 6 months | — | Abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea, flatulence, headache, nausea, rash[28] |

| Griseofulvin (fourth line) | — | Fingernails: 500–1,000mg daily for 6-9 months; toenails: 500–1,000mg daily for 12–18 months | — | Abdominal pain, agitation, confusion, depression, diarrhoea, dizziness, dyspepsia, fatigue, glossitis, hepatotoxicity, impaired hearing, kidney failure, leucopenia, menstrual disturbances, nausea, peripheral neuropathy, photosensitivity, rash, sleep disturbances, systemic lupus erythematosus, taste disturbances, vomiting[29] |

| Ameen M, Lear JT, Madan V et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of onychomycosis 2014. Br J Dermatol 2014;171(5):937–958[5] | ||||

Combination therapy

Topical and systematic combination therapy may provide synergistic antimicrobial activity. The BAD recommends this for patients who have responded poorly to topical treatment alone[5]

. Amorolfine 5% nail lacquer with systemic antifungals has been supported by a meta-analysis and systematic review to provide a higher percentage of total OM clearance compared with monotherapy of systemic terbinafine, without an increase in adverse effects[30]

.

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy combines light irradiation and a photosensitising drug to cause destruction of selected cells. Laser therapies, such as neodymiumyttrium-aluminum-garnet and low-level laser, are aimed to selectively inhibit fungal growth[31]

. These alternative therapies may be appropriate because they are selective to local infection and avoid systemic side effects; however, robust data are scarce[5]

and they are not offered on the NHS.

Lifestyle advice

According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), patients require advice around foot care in order to avoid and minimise exposure to situations that predispose individuals to OM (e.g. prolonged exposure to damp conditions, occlusive footwear, prevention of damaged nails and to ensure meticulous hygiene of the affected foot)[14]

.

Treatment must include a combination of proper hygiene and foot care as the risk of reinfection is high. Self-care to prevent infection should be stringently practiced until the fungus is eradicated, which may take up to 18 months[14]

.

Pharmacists should advise patients on nail care, washing and drying feet daily, using the correct footwear and encouraging the use of antifungal powder to help keep shoes pathogen free. See Box for important self-care messages.

Box: Lifestyle advice for foot care and hygiene

Do:

- Maintain good foot hygiene by washing feet daily, drying properly (especially in between the toes);

- Minimise exposure to environments that aggregate onychomycosis (e.g. warm, damp conditions);

- Wear well-fitted shoes that are non-occlusive to prevent trauma and limit perspiration;

- Replace all old shoes and old socks to prevent re-infection[32]

; - Wear breathable or antimicrobial socks (e.g. cotton, bamboo or sliver fibre);

- Treat all family members to prevent cross infection;

- Avoid nail trauma.

Do not:

- Apply cosmetic nail varnishes or artificial nails;

- Share nail clippers with others;

- Walk without footwear in public areas (e.g. gym, hotel rooms, saunas);

- Cut nails too short.

When to refer to podiatry

Before initiating topical or oral therapy, patients should ideally be referred to a podiatrist for nail trimming and debridement. This assists with removing as much fungus as possible and improves topical drug penetration. Debridement alone cannot be recommended for the treatment of OM; patients using a combination of debridement and topical nail lacquer have shown a significant improvement in mycological cure compared with debridement only[23]

. Patients with nail trauma owing to footwear, dystrophic toenails affecting other toes or who describe discomfort when walking owing to thickened toenails should also be referred.

When there is treatment failure with topical, oral and combination therapies, a podiatrist may be able to carry out a chemical or surgical nail avulsion (total nail removal or partial avulsion).

If there is doubt over the original diagnosis, or where no improvement has been seen with treatment, pharmacists should refer patients to a podiatrist or their GP.

Supported by RB

RB provided financial support in the production of this content.

The authors were paid by The Pharmaceutical Journal to write this article and full editorial control was maintained by the journal at all times.

References

[1] Elewski BE. Onychomycosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998;11(3):415–429. PMID: PMC88888

[2] Gupta AK, Versteeg SG & Shear NH. Onychomycosis in the 21st century: an update on diagnosis, epidemiology, and treatment. J Cutan Med Surg 2017;21(6):525–539. doi: 10.1177/1203475417716362

[3] Sigurgeirsson B & Baran R. The prevalence of onychomycosis in the global population: a literature study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28(11):1480–1491. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12323

[4] Eichenfield LF & Friedlander SF. Pediatric onychomycosis: the emerging role of topical therapy. J Drugs Dermatol 2017;16(2):105–109. PMID: 28300851

[5] Ameen M, Lear JT, Madan V et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of onychomycosis 2014. Br J Dermatol 2014;171(5):937–958. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13358

[6] Frowen P, O’Donnell M & Burrow JG. In: Lorimer D (ed). Podiatric management of the elderly. Neale’s Disorders of the Foot. 8th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

[7] Ross MH & Pawlina W. Histology: A text and atlas. 4th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. p447.

[8] Haneke E. Anatomy of the nail unit and the nail biopsy. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2015;34(2):95–100. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.2015.0143

[9] Campos S & Lencastre A. Dermatoscopic correlates of nail apparatus disease. In: Imaging in dermatology. Elsevier. 2016;43–58.

[10] Rubin AI, Jellinek NJ, Daniel RC, Scher RK (eds). Scher and Daniel’s nails: Diagnosis, surgery, therapy. 4th ed. Springer; 2018.

[11] Kreijkamp-Kaspers S, Hawke K, Guo L et al. Oral antifungal medication for toenail onychomycosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;(7):CD010031. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010031.pub2

[12] Abd Elmegeed ASM, Ouf SA, Moussa TAA & Eltahlawi SMR. Dermatophytes and other associated fungi in patients attending to some hospitals in Egypt. Braz J Microbiol 2015;46(3):799–805. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838246320140615

[13] White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2014;4(8): a019802. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019802

[14] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fungal nail infection; 2014. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/fungal-nail-infection#!diagnosissub:1 (accessed November 2018).

[15] Singal A & Khanna D. Onychomycosis: Diagnosis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013;77(6):659–672. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.86475

[16] Public Health England. Fungal skin and nail infections: Diagnosis and laboratory investigation. Public Health England: Protecting and improving the nation’s health 2017. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/619770/Fungal_skin_and_nail_infections_guidance.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[17] Fletcher CL, Hay RJ & Smeeton NC. Onychomycosis: the development of a clinical diagnostic aid for toenail disease. Part I. Establishing discriminating historical and clinical features. Br J Dermatol 2004;150(4):701–705. doi: 10.1111/j.0007-0963.2004.05871.x

[18] Eisman S & Sinclair R. Clinical Review. Fungal nail infection: diagnosis and management. BMJ 2014;(348):g1800. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1800

[19] Frowen P, O’Donnell M & Burrow JG. In: Lorimer D (ed). The skin and nails in podiatry. Neale’s Disorders of the Foot. 8th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

[20] Lipner, SR, Scher, RK & Ashourian, N. Onychomycosis (Tinea unguium, Nail fungal infection); 2017. Available at: https://www.dermatologyadvisor.com/dermatology/onychomycosis-tinea-unguium-nail-fungal-infection/article/691367/ (accessed November 2018)

[21] Electronic Medicines Compendium: Aspire Pharma Ltd. Amorolfine 5% w/v Medicated Nail Lacquer; 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7414/smpc (accessed November 2018)

[22] Reinel D. Topical treatment of onychomycosis with amorolfine 5% nail lacquer: comparative efficacy and tolerability of once and twice weekly use. Dermatology 1992;184(1):21–24. doi: 10.1159/000247612

[23] Malay DS, Yi S, Borowsky P et al. Efficacy of debridement alone versus debridement combined with topical antifungal nail lacquer for the treatment of pedal onychomycosis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Foot Ankle Surg 2009;48(3):294–308. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2008.12.012

[24] Electronic Medicines Compendium: Creo Pharma Limited. Tioconazole 283 mg/ml medicated nail laquer; 2017. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8643/smpc (accessed November 2018)

[25] British National Formulary. Terbinafine; 2018. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_203423860 (accessed November 2018)

[26] Electronic Medicines Compendium: Sandoz Limited. Itraconazole 100mg capsules; 2018. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7297/smpc (accessed November 2018)

[27] British National Formulary. Itraconazole; 2018. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_398441057 (accessed November 2018)

[28] British National Formulary. Fluconazole; 2018. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_870309169?hspl=Fluconazole (accessed November 2018)

[29] British National Formulary. Griseofulvin; 2018. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_101711937 (accessed November 2018)

[30] Feng X, Xiong X & Ran Y. Efficacy and tolerability of amorolfine 5% nail lacquer in combination with systemic antifungal agents for onychomycosis: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Dermatologic Therapy 2017;30(3). doi: 10.1111/dth.12457

[31] Kolodchenko VY & Baetul VI. A novel method for the treatment of fungal nail disease with 1064 nm Nd:YAG. J Laser Health Acad; 2013. Available at: https://www.laserandhealthacademy.com/media/objave/academy/priponke/42_47___kolodchenko___onychomycosis___jlaha_2013_1.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[32] Broughton RH. Reinfection from socks and shoes in tinae pedis. Br J Dermatol 1955;67(7):249–254. PMID:13239972

You might also be interested in…

The importance of diverse clinical imagery within health education

Entrustable professional activities: a new approach to supervising trainee pharmacists on clinical placements