Shutterstock.com

The Health Service Medical Supplies (Costs) Act (’the Act’) received Royal Assent on 27 April 2017 and as of 7 August 2017, the Act’s provisions are now in force. The Act reflects the UK government’s sensitivity to press reports that some pharmaceutical companies are charging extortionate prices for certain drugs. The main purpose of the Act is to prevent pharmaceutical companies from hiking the prices of generic medicines over which they have a virtual monopoly. It is also aimed at increasing the government’s ability to control medicine prices and to collect data enabling it to do so. The headlines focus on the Act’s aim of controlling the prices charged by manufacturers and wholesalers, but there may also be significant implications for pharmacy owners and how they are reimbursed for the medicines they supply.

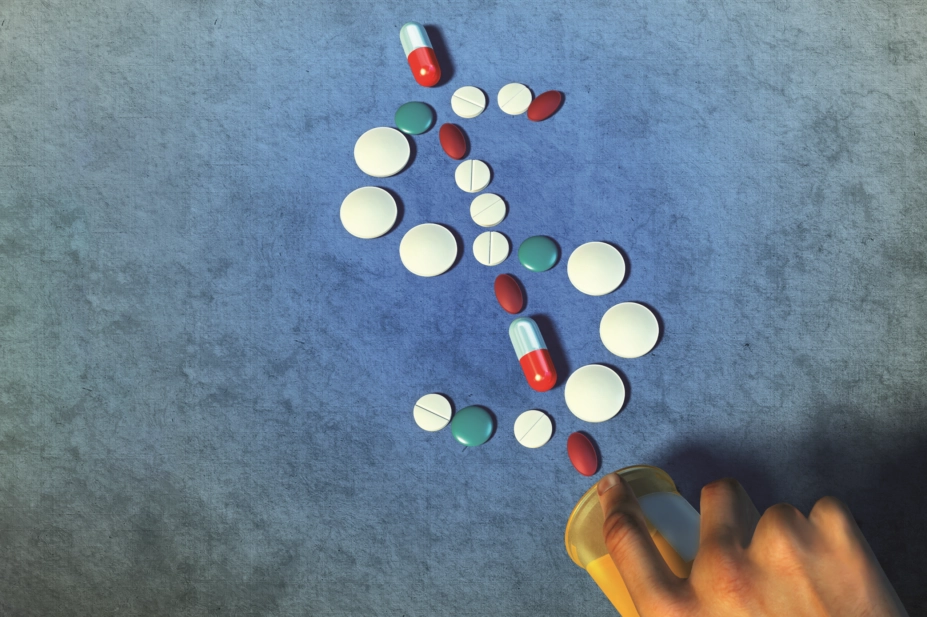

Increases in drug prices of between 500% and 2,500% have been denounced as ‘price gouging’

The Times ran a series of front-page stories about what is sometimes referred to as ‘price gouging’. For example, the varying prices of phenindione, an anticoagulant, rising from just under £100 for a packet of 25mg tablets to almost £300 in May 2015, only to increase again to £519.98 later that year. The price of Sinepin, an antidepressant, rose from £5.71 for a 28-pack of 50mg tablets to £154 for the same pack over 18 months. It has been claimed that companies are buying the rights to old medicines, debranding them and raising their prices. They do this by exploiting both lack of competition and the medicines’ re-categorisation under the Drug Tariff, which outlines what will be paid to pharmacy contractors for NHS services provided either for reimbursement or for remuneration. The practice is estimated to cost the NHS £262m a year[1]

.

How the new Act will work

Many pharmaceutical manufacturers and suppliers are part of the government’s voluntary Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS), which controls the pricing of branded medicines. Before the new Act came into force, the National Health Service Act 2006 (Section 262 NHS Act)[2]

prevented the government from controlling the prices charged for any medicine by a manufacturer or supplier if they were part of the PPRS, even in relation to unbranded medicines (which are not covered by the scheme). This created a loophole, allowing some companies which are party to the PPRS to debrand medicines which are not available from other companies, and then significantly increase prices.

The government can now control the prices of generic medicines

The Act limits the prohibition in the NHS Act on controlling prices to branded medicines covered by the PPRS, which will no longer cover unbranded medicines (Section 4 of the Act replacing s.262(2) NHS Act). As a result, the government can now control the prices of these generic medicines. In addition, the Act clarifies the government’s power to require companies to make payments to control the cost of health service medicines (Section 5(2)(d) of the Act inserting s.263(1)(c) into the NHS Act).

Should any organisation fail to comply with regulations created under the new law, which may include exceeding a price cap or failure to record or provide requested information under a statutory scheme, they may face financial penalties. The current maximum penalty for failure to comply with regulations is a fine of up to either £10,000 for each day of non-compliance, or £100,000 as a single payment (Section 265 NHS Act 2006). Pharmaceutical companies should therefore keep a close eye on any new regulations arising from the new law.

The Act also strengthens the basis on which the government can collect data on the sale and purchase of medicines from all parts of the supply chain. The key purpose of obtaining this data is to assess the sums which pharmacists are reimbursed for medicines. This will enable the government to calculate reimbursement figures which more accurately reflect market prices. During the Act’s passage through Parliament, a new sub-section (Section 1 of the Act inserting s.164(8A) to (8E) into the NHS Act) — not in the original Bill — was added about special medicinal products (‘specials’). It extends to anyone who is remunerated for providing pharmaceutical services (such as pharmacy owners). This sub-section can require inquiries to be made to ensure that the level of remuneration for specials is reasonable, or to estimate an amount of remuneration that is reasonable.

In addition, the Act includes a new power to create regulations requiring any person who manufactures, distributes, or supplies medicines to be used in connection with the NHS (which would appear to include pharmacies) to keep records (section 8 of the Act, inserting s.264A-C into the NHS Act). These records must be disclosed to the Department of Health (DH), NHS England or similar bodies where provided with an ‘information notice’, which can be appealed.

This is a broad power that may apply to any information that might be required to determine the payments of doctors and pharmacists, whether adequate supplies of medicines are available, and whether they are available on terms which represent value for money. Information that would facilitate the exercise of the government’s powers to control prices or operate statutory or voluntary schemes (such as the PPRS) will also be relevant, and the new regulations may (or may not) narrow down the wide scope of these powers.

Pharmacists could face investigation by the General Pharmaceutical Council if they fail to provide required data

If a pharmacy fails to comply with a requirement to provide data or assist with lawful queries under the Act, not only might it be liable to pay a large penalty, but also its superintendent or responsible pharmacist could face investigation from the UK pharmacy regulator, the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC). Under the new set of standards issued by the GPhC, pharmacists must ‘work in partnership with others’, and this includes public health officials[3]

. Failure to provide information could therefore result in professional, as well as financial, sanctions. Once the regulations are published, it will become clearer what pharmacists need to do to comply with requests, and how frequent any such requests are likely to be.

Reimbursements

The powers to require inquiries to be made (for specials) and obtain data (for both specials and other health service products) may be used to control what pharmacies are currently paid to reimburse them for the medicines supplied to patients. This might include how pharmacies are reimbursed for specials and for medicines that do not have a fixed price in Part VIII of the Drug Tariff (NP8 items). These items can be costly to the NHS. Both clinical commissioning groups and the GPhC have previously considered whether action can be taken against certain pharmacy owners who could have supplied an alternative item at lower cost. So far, steps of that kind have been fruitless. The GPhC has dropped cases in which it had accused pharmacists of misconduct in failing to secure best value for the NHS because price is not the only determining factor when a pharmacy owner chooses a particular supplier; other factors include availability, quality of service and speed of supply.

New requirements will impose a further burden on pharmacies

Requiring extra information to be provided and queries answered will impose a further burden on pharmacies and particularly on pharmaceutical companies, which are already under duties to submit to the DH spreadsheets and invoices to evidence a range of data. However, the government has stated that, at least in relation to profits and revenue information, it will only use this additional power to require information when there are concerns that value for money is not being delivered (although this does, of course, allow the government a rather broad ambit), and that it will not be used on a routine basis[4]

.

There is little detail in the Act. Instead, ministers are given the power to make regulations. Any such regulations will need careful scrutiny to assess the effect on the provision of pharmaceutical services.

Review practices

Pharmaceutical manufacturers and wholesale suppliers may need to review their practices as a result of the new Act. Much may depend on the precise wording of any regulations. Community pharmacies will also need to be alert to the possible effect of any regulations because the powers to control prices may not be confined to pharmaceutical manufacturers and wholesalers. Profits on drugs are a recognised part of remuneration for NHS pharmaceutical services and for some pharmacies, controls on reimbursement prices would be an unwelcome measure, coinciding with pharmacy cuts that the High Court has held are lawful despite the severity of their impact.

In summary, expanding price controls to unbranded medicines owned by producers party to the PPRS scheme should go some way to achieve the government’s objective of reducing ‘price-gouging’. In light of the as-yet unpublished regulations filling out the skeleton of the Act, it remains to be seen how frequently data-collecting powers will be used, particularly in relation to pharmacies, where their use could be seen as unnecessarily intrusive. The government’s requirement to consult before preparing regulations may temper the laws before they come into force.

Andrew Sweetman is an associate solicitor in the healthcare regulation team at Charles Russell Speechlys LLP.

References

[1] Kenber B. NHS failure on medicine prices costs public £125m. The Times 16 August 2016. Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/nhs-failure-on-medicine-prices-costs-public-125m-j2jtb02xw (accessed October 2017)

[2] NHS Health Service Act 2006. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/41/contents (accessed October 2017)

[3] General Pharmaceutical Council. Standards for pharmacy professionals. May 2017. Available at: https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/standards_for_pharmacy_professionals_may_2017_0.pdf (accessed October 2017)

[4] Department of Health. Health Service Medical Supplies (Costs) Bill factsheet. Updated 8 November 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-service-medical-supplies-costs/health-service-medical-supplies-costs-bill-factsheet (accessed October 2017)